SINGUR (India): The world’s cheapest car may be coming to India soon, but at a price.

For years, Asha Patra and her husband tilled their land in eastern India for a meagre but stable living. Then the communist state government walled it off for a factory to make the world’s cheapest car, Tata Motor’s Nano, dubbed India’s “People’s Car”.

With no land left, they switched to a tea shop, but their pots and cups were stolen three times. Unable to make ends meet, Patra sold her gold earrings, one of her few valuable family possessions, for Rs1,300.

Her husband soon became silent, withdrawn and stopped eating. One day in December he went to a cow shed and hanged himself.

“He was still alive when they found him but he died minutes later,” said Patra. Her expressionless face was half-covered with a shawl in her mud hut near the factory wall. “The factory was the problem. Otherwise we could earn a living.”

Tata Motors, a unit of Indian conglomerate Tata group, is preparing in October to start rolling out thousands of Nanos from its new state-of-the-art factory at a 1,000 acre complex in Singur, a cluster of villages an hour’s drive from Kolkata, capital of West Bengal state.

Eventually some 250,000 cars a year will be produced in a project that has cost Tata about $375 million. Auto makers globally are wondering if the Nano, selling at about $2,500, can successfully revolutionise cheap car design.

In India, it has become a nationalist symbol. One newspaper compared its unveiling in January to Man walking on the moon.

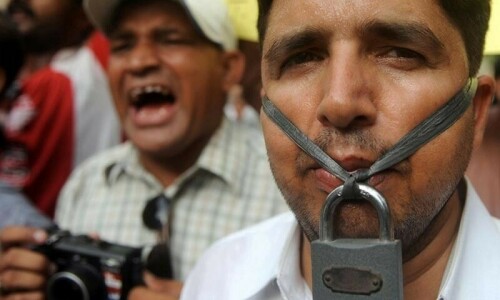

But back on earth, many villagers like Patra are ineligible or unwilling to accept compensation from West Bengal’s government for the loss of land. They have protested for more than a year, and vow to overshadow the Nano’s so far good publicity.

But time is against the villagers. Their home grain supplies and savings are dwindling. Four farmers have committed suicide. Others survive on neighbours’ handouts.

“It’s a battle of nerves. They’re wondering how long we can face these hardships,” said Prosenjit Das, a protest leader.

“But no factory with so many disputes and needing so many police can bring out its product. The factory needs locals to operate.”

Villagers vow to be a headache for Tata Motors’ operations.

They plan to appeal to the Supreme Court and blockade access roads.

The protests are a reminder of the obstacles India faces in industrialising and competing with the likes of China as villagers, two-thirds of a 1.1 billion population, demand to be heard. The state of India’s farmers promises to be one of the biggest issues ahead of a likely 2009 general election.

Other protests over industrial plans have hit India in the last year. West Bengal already shelved plans for a chemical hub in Nandigram after dozens of villagers died in protests.

The problem is that land with good access and transport for industry is scarce.

Many villagers have accepted compensation packages for the seizure of their land, the state government says.

“A significant majority have accepted. Others have not. It’s their choice,” Industries Secretary Sabyasachi Sen said.

Village leaders say owners of 337 acres, mainly poorer small holders, have rejected any compensation, and will fight.

Even some wealthier farmers entitled to large amounts of cash are holding out. Many economists say interest paid on cash compensation packages do not make up for returns on farms.

“Land is our mother, and we don’t give away our mother,” said Paramita Das, a middle-aged woman. Her family had some 1.5 acres.

The new Tata factory, with its stadium-like silhouette dominating the landscape, looks unstoppable. Dozens of trucks roll over dug-up land. Concrete springs up everywhere.

It was easy to see why Singur was chosen. It lies close to a major highway, a railway and access to a port. It is near a Tata steel factory in the neighbouring state of Jharkhand.

Tata says the project will create more than 10,000 jobs and points to a high court judgment in January that rejected petitions from villagers the plant was illegal.

“Tata Motors is confident that the plant will become a catalyst for both greater well-being of Singur families and growth in the region,” Tata said in a statement .

That does not resonate among many villagers. Many sharecroppers — farmers who work land in return for a crop share — and landless labourers are not entitled to compensation.

Some villagers who sold up have had second thoughts.

“Most of those I know who have sold did so out of fear,” said 48-year-old Ashok Ghose, referring to concerns that unclear land titles could rob many farmers of compensation.

Ghose says he received about $30,000 for just over an acre of land. He wants to marry off three daughters with the money. After that he will be left with just six cows.

“The factory may harm us. The price of rice and vegetables have gone up a lot already,” Ghose said.

But this is one of the state’s showcase projects to persuade hi-tech global companies to set up here.

“We want West Bengal to become a car-making hub,” Sen said.

Villagers face an uphill battle against India’s economic juggernaut.

“There’s a depression at the moment, a lot of suffering,” said Anuradha Talwar, an agricultural leader who also advises India’s Supreme Court on issues of hunger in West Bengal.

“But Nano will always be overshadowed by what’s happened in Singur. This protest will not be a lost cause.”

—Reuters

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.