NEW DELHI: Steel, marble and granite are high on the list of materials needed to build homes in well-to-do suburbs on the outskirts of India’s sprawling capital but so are plastic sheets, cardboard and reeds.

As fields increasingly sprout concrete and glass condos in place of wheat and mustard, shanty towns too have grown to house tens of thousands pushed out as New Delhi expands its “world-class” ambitions.

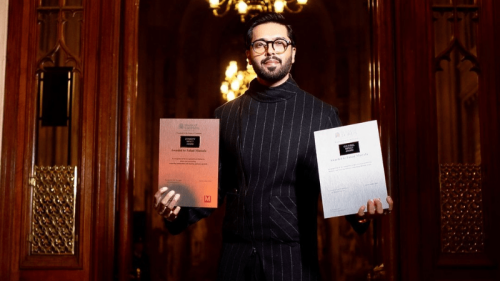

Mannequin maker Mohammed Nasir used to live on the river bank, where a sports village is now being constructed as the capital prepares to host the Commonwealth Games in 2010.

“They said they needed to make room for all those who were going to come for the games,” said Mohammed Nasir, 24, recalling the visits from politicians two years ago.After the speeches, bulldozers tore down his home and Nasir and his family ended up on the streets.

They leased a tiny plot in a three-year-old shanty, or jhuggi, called Savda Ghevra, 40 kilometres northwest of the city centre.

There, they built a reed hut.

Five years ago, as the city embarked on a huge redevelopment drive, the Supreme Court cleared the way for mass evictions from prime land, ruling that the government need not provide squatters with alternative housing.

Redevelopment advocates cheered.

But in a booming city of 17 million where much of the land is owned by government agencies that have failed to construct enough housing, at least half the population has been forced to squat in slums or other illegal housing, according to official figures.

It’s a nationwide problem, with slums multiplying 70 per cent in the decade since 1991, when India introduced market reforms.

Millions have flocked to urban centres for work, contributing to the current housing shortage of 25 million homes across Indian cities.

In one respect, the markets have done their work.

Tens of thousands of middle-class families have used newly-available credit to buy homes with marble floors, built by private developers to the south and east of Delhi.

Banks say that over 40 per cent of housing loans issued in the capital region go to the southern suburb of Gurgaon, home to gated communities and call centres.

Developers expect to add more than 45.4 million square metres of housing around Delhi and six other cities in the next three years, according to global real estate consultant Knight Frank.

Most will become apartments and villas starting at $80,000, putting them far out of the reach of blue-collar workers such as Nasir.

“The market is not catering to those kinds of (people),” says housing official Prasanna K. Mohanty.

He directs a national urban renewal plan that will spend five billion dollars on affordable housing by 2012, but his ministry estimates that India needs to spend 20 times that amount.

In Delhi, the city government is experimenting with building 100,000 flats to be sold at prices starting at $2,500 to low-income beneficiaries selected in a lottery.

Developers say similar schemes in the past have seen brokers cajole lottery winners into parting with their flats for a modest markup, only to sell them again at market rates.

“You might not see a single person of that category living in that house,” said Rajesh Katyal, chief operating officer of Ansal Property and Infrastructure Ltd, which has set aside land and flats for low-income residents in its townships in Gurgaon.

For now, the main plank of the city’s affordable housing plan involves leasing land in new suburban shanties to evicted slum dwellers who can prove they lived in Delhi for a decade or more.

The land is a steal compared to market rates, but leaseholders receive no help with building homes and there are few good jobs on the city’s frontiers.

In a nightmare version of the suburban dream, many still live in the reed huts they built when they first moved there.

Non-profit groups have tried to help in five-year-old Bawana shanty town the US-based Robin Raina foundation is building homes for families earning less than $100 a month but most areas still lack water and sanitation.

“The whole move to the resettlement areas was fundamentally flawed,” said UN special rapporteur on housing Miloon Kothari, who estimates that half a million people have been evicted from Delhi slums in the past five years.

“People ended up being worse off than they were.” Nasir’s family saw their income plummet from about $300 a month to perhaps two-thirds of that figure.

Sharif Ahmed, Nasir’s 55-year-old father, has given up going to the fish market where he used to earn more than $100 a month, because he is now a two-and-half-hour bus ride away.

An older brother sleeps at the fish market to avoid the commute, travelling home to see his wife and children every 10 days.

The family has dug into their savings to pay for the $175 lease and to plaster and whitewash the walls of their 12-square-metre hut.

They don’t dare spend more, fearing a repeat of the evictions of two years ago when their lease expires in 10 years.

Commuting fives hours to and from his old job now costs Nasir a quarter of his $50 monthly salary in bus fare.“There’s just a road and empty land where we used to live,” he says.

The river bed won’t be empty long the city and a private developer are turning chunks of it into sports arenas, a mall and housing for international athletes.

After the Commonwealth Games, the air-conditioned apartments are expected to sell for at least half a million dollars each.—AFP

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.