The issue of insider trading, a menace that plagued the stock markets, has finally received the attention of the policy makers. In the new federal budget, the coalition government has prohibited insider trading. Any person found guilty of it will have to pay a fine of Rs10 million or three times the amount of gain or loss avoided by him or loss suffered by another person, whichever amount being higher.

The issue of insider trading, a menace that plagued the stock markets, has finally received the attention of the policy makers. In the new federal budget, the coalition government has prohibited insider trading. Any person found guilty of it will have to pay a fine of Rs10 million or three times the amount of gain or loss avoided by him or loss suffered by another person, whichever amount being higher.

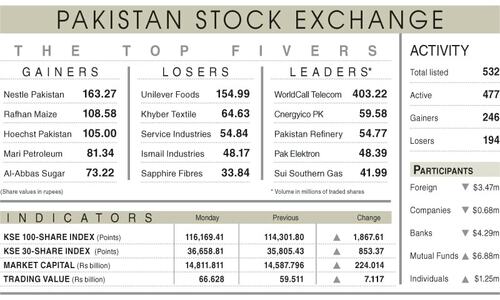

In the second quarter-to-date, the KSE-100 index has lost 17.4 per cent. Although the reasons are more related to the current state of political uncertainty and the economic concerns, market microstructure is a necessary ingredient of confidence.

Laws for regulating insider trading activities and for punishing those involved in such acts have been long overdue. Until now, investors had no protection from those who indulge in insider trading, an activity that involves trading on “inside information”.

Inside information is generally defined as information about a company that is both materially significant but not known by the public. According to the Finance Bill, inside information means information, which has not been made public, relating, directly or indirectly to listed securities or any or more issuers and which, if it were made public, would be likely to have an effect on the prices of those listed securities or on the price of related securities; in relation to derivatives on commodities.

Under the US securities laws, for instance, information is material if an investor is likely to consider it significant in making an investment or trading decision, or if the information is likely to have a substantial impact on the stock price of a company. The Insider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act (ITSFEA) that has been in effect since 1988, specifies sanctions for insider trading in the US.

According to the Finance Bill, an insider found guilty may be directed by the Security Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) to surrender to it, an amount equivalent to the gain made or loss avoided by him; or to pay any other person who has suffered a loss, an amount equivalent to the loss so suffered by such persons; and may, where such person is an executive officer, director, auditor, advisor or consultant of a listed company, be removed from such office by an order of the SECP and debarred from auditing any listed company for a period of up to three years.

This is a long overdue and pragmatic step in the correct direction to enhance market integrity and protect the small investor. A “small investor” is someone who does not possess the financial capacity to utilise economies of scale while investing and trading in financial markets. He operates with limited financial appetite that is directly proportional to his risk tolerance level.

This type of investor cannot move markets on his own. Such an investor also falls in the minority shareholders category and is at the mercy of the majority shareholders, who exercise control over the company. Small investors (and shareholders) have even less influence than their stake warrants. At times, this can have detrimental affects on corporate valuation.

Small investor protection is important because such protection serves as a major confidence-building measure for capital markets over the longer term and attracts asset allocation from this segment of investors. For a market to have a stable, broad investor base, especially a non-institutional one, small investor protection is critical. In general, the more legal protection minorities enjoy, the more they will want to invest. Past research has shown that stock markets as a whole are larger and more liquid when investors are better protected.

A good system of corporate governance should protect investors against expropriation by insiders and allow shareholders access to a certain minimum acceptable level of corporate information. What is that “minimum acceptable level” is subjective and varies from one country to another. In the US, the creation of a system based on accurate disclosure has proved remarkably successful. Though Wall Street resisted it, the establishment of the Securities and Exchange Commission with its emphasis on financial transparency, staved off far more burdensome regulation.

A law against insider trading was badly needed badly. Now that we have it, its implementation will need to be carefully monitored and evaluated. The challenge will be to ensure the quick and efficient execution of provisions under the law to punish those engaged in insider trading and compensate the victims. Above all, the market and investing public has to perceive it as being objectively enforced and implemented. But will it?

The writer is the EVP and head of the Investment Management, Morgan Stanley ( Saudi Arabia). This article represents his personal views.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.