Some ominous developments

INDIA takes great pride in its claim to be the world’s largest functioning democracy — a claim not altogether without some truth to it.

This does not however mean that New Delhi shows special consideration for democratic governments in neighbouring states. In fact, as devoted students of Chanakya (an illustrious predecessor of Machiavelli), they cannot but be skilful practitioners of realpolitik.

Some of our politicians may have hoped that New Delhi would look with favour upon a recently restored democratic government in Pakistan, but India remains wedded to its traditional approaches. If anything, India appears to have ratcheted up its diatribe against Pakistan. Much of it has been repetitive, both in content and presentation, and revolves primarily around allegations that Pakistani intelligence and security agencies are hand in glove with extremists and terrorists. India also holds Pakistan responsible for increased militancy in occupied Kashmir. But what is deeply worrying is a new stridency in New Delhi’s pronouncements.

The depth of the distrust that pervades Pakistan-India bilateral ties came out in a most dramatic fashion during the meeting of the foreign secretaries in New Delhi on July 21. Though it was an inaugural session of the fifth round of the composite dialogue process, the Indians refused to let diplomatic niceties hide their annoyance with Pakistan.

The Indian foreign secretary, in his press comments, charged that the attack on India’s embassy in Kabul on July 7 had been carried out with the help and connivance of Pakistan’s intelligence agencies and that this had placed the dialogue process under “stress”. Menon added that the talks were taking place at a “difficult time in our relationship with Pakistan”, especially as “there have been several issues in the recent past which have vitiated the atmosphere”. In this context, he referred to violations on the Line of Control, cross-border terrorism, incitement to violence in Kashmir and public statements by Pakistani leaders who were “reverting to the old polemics”.

Pakistan’s new foreign secretary, Salman Bashir, a cool and skilful diplomat, however refused to be ensnared in the blame game, but affirmed that “we do not have to prove our credentials to anyone. We are engaged at the forefront of the fight against terror”. He also warned India that the blame game could be played by both sides, as Pakistan had evidence of Indian involvement in Balochistan and Fata.

Admittedly, the suicide bomb attack on the embassy in Kabul must have been a painful shock to the Indians, especially as it resulted in the death of two senior officials, one of whom was involved in intelligence activities. But the speed and stridency of the Indian reaction betrayed an inbuilt mistrust of Pakistan. Even more disconcerting was the harsh and intemperate words used by the Indian national security adviser, who not only accused Pakistan of involvement in the attack but also demanded the “destruction” of the ISI. To make such a demand without even waiting for the probe’s results was uncalled for, especially as the Indians have so far not shared any evidence that could point in our direction.

To our good fortune, the Bush administration refused to endorse the Indian charges while calling on the two governments to share available intelligence on the subject. It nevertheless appears that New Delhi has reached the conclusion that the recent Taliban resurgence has opened up fresh opportunities that could be exploited to its advantage. After all, it has long been India’s aim to paint Pakistan with the tar brush of terrorism, an effort that was most pronounced in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, when it launched a major campaign to arrogate to itself the same right to unilateral action claimed by the Bush administration.

Now, with the Bush administration’s growing alarm over the Taliban resurgence and its annoyance with what it suspects is a lackadaisical attitude of the democratic government in Pakistan, New Delhi has seized, with gusto, the opportunity to join in the chorus of denunciations emanating from Washington. It recognises that this plays well with powerful elements in the US while allowing it to reinforce its presence in Afghanistan, and of course keeping Islamabad off balance in relations with other powers.

Manmohan Singh is a pragmatic politician with little regard for ideological considerations, as demonstrated by his determination to obtain the Lok Sabha’s approval of the nuclear deal with the US, going to the extent of risking his government. Some may accuse him of having “engaged in subterfuge, stealth and deception” in imposing the nuclear deal (as claimed by veteran journalist Praful Bidwai), but to the victor go the spoils of the day.

It also confirms the assessment of analysts, including this scribe, that the nuclear deal should not be seen merely as bringing nuclear technology to India. It is a far more important development that contains within it the seeds of a strategic partnership between the US and India that is likely to have major implications for Pakistan and the region. It also represents the formal abandonment of India’s long-held policy of not being tied to any superpower, as well as America’s recognition of India’s status as a nuclear weapons state.

In fact, acceptance of this country-specific concession by the IAEA and the NSG would be disastrous for the international non-proliferation regime. This needs to be resisted vigorously, for it would sanctify Pakistan’s clearly discriminatory treatment vis-à-vis India.

The current warmth between India and the US was initiated by Clinton but deepened by Bush. And Obama has spoken of his determination to focus on India, along with Japan, Korea and Australia, “to create a stable and prosperous Asia”. As far as Pakistan is concerned, Obama sees the “cave-spotted mountains of Northern Pakistan”, with the same, if not greater, concern than “the centrifuges spinning beneath Iran’s soil”. This is all indicative of the way the wind is blowing in Washington.

Do we see the first signs of a nexus between the US, India and Afghanistan, to come down hard on Pakistan? Though a partner of the US in the war on terror and a non-Nato ally to boot, we are likely to come under increased pressure to ‘do more’, even if it means greater turmoil within Pakistan. Prime Minister Gilani was likely impressed by the glamour of the White House welcome, but the gathering clouds portend ominous developments that call for a strong, resolute and clear-headed leadership.

Pacifying the Baloch

THE relative quiet with which Balochistan’s militant nationalists had been watching political developments in the country has been broken by Brahmdakh Bugti’s strident call for a sovereign Balochistan.

Before rushing to issue any edict against the angry Baloch one will serve Pakistan well by pondering his words and the context.

The late Akbar Bugti’s grandson is not the first Baloch politician to defend armed action against the Pakistan state, but he has spoken at a time when the people of Balochistan have become more receptive to his ideas. The Baloch like to tell their tale of misery in a dirge. Its present version has features that should convince Islamabad of the urgency of addressing Balochistan’s alienation.

The traditional lament used to begin with the way British Balochistan’s vote to join Pakistan was secured and the pledges to Kalat broken. Then came violations of the right to provincial autonomy, the imposition of One Unit, dismissal of its elected governments, detention of its popular leaders, military operations, killing of sardars, and expropriation of the province’s natural resources. Each federal government provided grist to the lament writer’s mill.

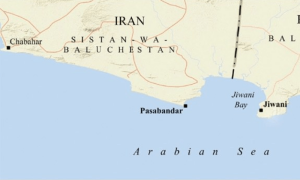

The Musharraf regime outdid its predecessors. It not only added Gwadar, new cantonment plans, Akbar Bugti’s killing and disappearances to Balochistan’s festering sores, it also dared the nationalists to climb the mountains and put a seal on its implacability by dismissing the recommendations of the Senate committee, which meant Balochistan was not entitled to a friendly counsel even.

Lately, the dissidents in Balochistan have evolved a new idiom to describe the seizure and control of their gold (from Saindak) and gas. The various parts of Pakistan, and some foreign parties too, are benefiting from Balochistan’s wealth, so goes the lament, while its own population is left to wallow in poverty, disease and ignorance. This version of the Balochistan lament has a more direct appeal to the ordinary citizen than the grievances in the earlier versions.

The main reason is evidence of Balochistan’s exploitation that is easily visible and is tangible, such as the long lines of vehicles at CNG filling stations in Quetta as there is not enough gas for the territory that produces it. Large segments of the road called the RCD Highway (Quetta to Karachi) disappeared in a flood two years ago. Everybody travelling on the dusty and stony track is reminded that Balochistan cannot have carpeted roads such as other provinces have.

Word is out that around 75 per cent of the relief goods provided by foreign donors did not reach the flood-affected people. The plight of thousands of internally displaced persons cannot be concealed from the local youth who can see emaciated people camping in the open with nobody responsible for providing them with food and medicines or tents even. A Baloch youth might not have felt so strongly about constitutional matters as he does about the disappearance of a cousin.

The transformation of impersonal grievances into personal complaints has radicalised a larger proportion of the province’s youth population than before. They have also found new symbols of unity. The killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti made him a much greater hero than he was in life. Some of the most common roadside slogans hail the late Ballach Marri and Brahmdakh Bugti, indicating their adoption as heroes across political divides.

Nobody is therefore surprised to find that the traditional parties and their moderate leaders have lost their audiences. Most observers agree that the old formulas for greater autonomy and the abolition of the concurrent list can no longer overcome Balochistan’s alienation. Many greyheads assert that the phase of placating Balochistan through negotiations is over.

However, the way a new provincial cabinet was cobbled together did not fail to offer comfort to the federal establishment that the politics of patronage had not ended and that it was still possible to recruit people with some electoral following who were prepared to support the federal connection. The installation of a coalition government in Islamabad and the chorus of democratic rhetoric from the citadels of power revived hopes of reconciliation in the moderate political parties. Many of them defined a set of preconditions for negotiations with the centre. These included:

Recovery of all missing persons; release of all political detainees and withdrawal of cases against political activists; return of IDPs to their homes; replacement of the Frontier Constabulary with the traditional Levies; cessation of the handing over of Baloch people to Iran; and end to military operations and land-grab designs.

Once these demands were met talks could begin on substantial issues, such as review of legislative lists and emergency provisions of the constitution, revision of royalty rates for gas, Balochistan’s say in federal policies and its right to seek foreign investment and trading partners, and a new NFC award.

Unfortunately, hopes of an Islamabad-Quetta accord started waning as the new federal government revealed its capacity for wobbling. Indications that the pre-election establishment was still calling the shots have caused a setback to the pro-federation elements in Balochistan. Let there be no doubt that Balochistan can remain a willing constituent of the federation only if a genuinely democratic order endures both at the centre and in the provinces. The more Islamabad lunges in favour of praetorian rule the faster will be Balochistan’s drift away from the federation. The onus of keeping Balochistan in the federation is not on Brahmdakh Bugti, it is on Islamabad, that is if it believes in a federal Pakistan at all.

It may still be possible to win over the minds and hearts of the Baloch by meeting the preconditions for negotiations mentioned above and encouraging a discourse on the imperatives of a durable federation. Keeping the Waseem Sajjad committee’s recommendations secret has been counter-productive. Let all relevant reports and recommendations be made public. The task of drawing up a comprehensive package on provincial autonomy may be assigned to a special committee comprising representatives of the centre and all the four provinces. This committee will succeed only if the powers that be are prepared to guarantee Balochistan (and other provinces, for that matter) a place in the federation compatible with its right to dignity, justice and self-governance.

Alternative futures

YOU have to hand it to the economics team at Goldman Sachs. It was they who came up with the concept of the “BRICs”: the four big economies, in Brazil, Russia, India and China, that were going to catch up with and then overtake the big economies of the developed world.

More recently they added the “Next Eleven”: middle-sized developing countries like Turkey, Indonesia and Mexico that will also grow fast enough to overtake their old-rich counterparts in the next generation.

Back in 2006, Goldman Sachs predicted that the Chinese economy would surpass that of the United States in the early 2040s, with the Indian economy not far behind. But now the Goldman Sachs team has put out a new set of forecasts.

The Chinese economy, they predict, will overtake the US economy around 2025, not in the 2040s, and will be twice as big by 2050. India’s economy by 2050 will still be slightly smaller than that of the United States, but the economies of Brazil, Russia, Indonesia and Mexico will all be bigger than that of the next-largest old-rich country, Britain.

The changes in the pecking order are equally dramatic further down. Turkey’s economy in 2050 will be bigger than Japan’s, France’s or Germany’s, and both Nigeria and the Philippines will have larger economies than Canada and Italy. South Korea, Iran and Saudi Arabia will all have bigger economies than Spain. The predicted changes in per capita income by 2050 are less radical, though still impressive. The United States and the United Kingdom are neck-and-neck at the top, just as they are now, with Canada only slightly behind. Koreans are substantially richer than Japanese — $80,000 per annum versus $63,000 — and the Chinese still bring up the rear in East Asia with a mere $50,000 a year.

But hang on a minute. $50,000 a year is slightly higher than the present per capita income in the US or Britain. In 2050 there will be around one and a half billion Chinese, and if they have an average per capita income of $50,000 a year then most of them will be leading a fairly lavish middle-class lifestyle. How is this compatible with what we know about the world’s resources of energy, food and other commodities, and about the likely course of climate change?

Goldman Sachs is providing surprise-free projections of current trends. This is a useful exercise, because it sets the larger framework in which the inevitable surprises will take place. But that is all it is, because no forty-year stretch of history is free of surprises.

In the past forty years we have seen the rise to great wealth of the oil-exporting states of the Arabian peninsula, but a crash in the predicted Iranian growth rate after the 1979 revolution. We have seen the disappointment of the high expectations most people held for newly independent African countries in the 1960s, and the sudden high growth rates of most Asian countries in the 1980s and 1990s.

Few economic analysts in 1968 predicted any of this, any more than they foresaw globalisation, the internet or the rise of the euro. History does not run on rails, and none of those things was certain to happen (though some had a much higher probability of happening than others). The same applies to the relationship between the present and the future: Goldman Sachs is offering us a point of departure for thinking about the future, not a map of it.

So what are some of the things that could derail this simple picture of a richer future in which the gap between rich and poor has narrowed sharply except for Africa? A mere shortage of oil or other commodities wouldn’t change the pecking order much, although it might lower everybody’s average income (except in the commodity-exporting countries). Local political upheavals might knock specific countries out of the running, like Iran in the 1980s or Russia in the 1990s, but that wouldn’t change the broader picture either.

The one “known unknown” that could do that is large-scale climate change, because it would strike some countries much harder than others, at least in the early phase. And the hardest-hit countries would include most of those that are now climbing rapidly in the rankings.

Countries in the tropics and the sub-tropics are likely to be hit early and hard by climate change, while most of those in the temperate climate zone will suffer relatively little until a good deal later in the process. Countries like Turkey, Mexico, Indonesia, India and Iran will suffer diminished rainfall and declining food production, and even China, although mostly in the temperate zone, will struggle as the glaciers on the Tibetan plateau that feed most of its major rivers melt away.

Since the countries that suffer least, like the US, Canada, Britain, France, Germany, Russia and Japan, are also the ones that produced most of the greenhouse-gas emissions that have caused the current warming, this will probably result in some very bitter exchanges between North and South. But it also means that the economic pecking order in 2050 may be less different from today’s than Goldman Sachs predicts. n

— Copyright Gwynne Dyer