There was a belief that I shared that the developing countries would be spared the devastation caused by the recent and unrelenting meltdown in the financial system of the United States.

There was a belief that I shared that the developing countries would be spared the devastation caused by the recent and unrelenting meltdown in the financial system of the United States.

We thought that the countries that would be really affected would be those that had their financial systems closely integrated with that of the United States. That meant Western Europe and Japan. That would have been the case had the crisis been contained to the financial sector. However, in early October, it began to affect the real sectors of the economy, the commodity producing sectors. Once that happened, the developing world was pulled into the vortex. This happened in many ways. From Pakistan’s perspective, the most important of these was the decline in the price of commodities. This will have short-term positive consequences for Pakistan as the price of oil has declined by 40 per and that of some of the agricultural commodities the country imports by 11 per cent. Does his mean that we should reformulate some of the bases on which I had been suggesting we should develop our long-term growth strategy? I had argued for developing agriculture as the main source of dynamism for the country’s economy. Is that argument still valid?

The answer to this question involves a discussion of the process of globalisation and look at the trends in the prices of energy and food.

The process of globalisation began to impact the developing world in many different ways. Economists who began to look at this phenomenon interpreted it as affecting the links among different parts of the global economy. Trade as a proportion of global output began to increase significantly; large amounts of both short and medium-term capital began to flow across national borders; the structure of manufacturing changed as firm’s began to locate production in different locations, given the advantages that were available; outsourcing became an important part of modern services. Most commentators saw the process as a positive development for all countries that were deeply engaged in it. The unprecedented increase in global output in the 1990s seemed to vindicate this point of view.

However, what was not seen at that time was that globalisation would also lead to the rise of new economies with their own dynamics. While China, the world’s most populous country, had seen its economy grow at double-digit rates which meant that the size of its economy doubled every six or seven years over a quarter century, India also climbed on to the rapid growth strategy. India, with its population not much smaller than that of China, has had rates of GDP growth close to eight per cent a year for the last decade and a half. Both countries took advantage of the expansion in international trade, change in the system of industrial production, outsourcing of services and large flow of skilled people across international borders. What the economists working in the area of globalisation had not anticipated was the sharp increase in commodity prices that will result from the rapid growth in the economies of large developing countries.

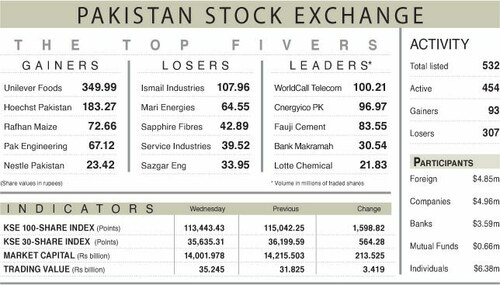

It is now recognised that the sharp escalation is commodity prices was not the consequence of short-term events such as weather failure (in the case of agricultural products) or a sudden change in some aspect of the industrial process (in the case of industrial inputs). It represented a paradigm shift. The accompanying table provides the indices of food and energy prices estimated by the International Monetary Fund for its report to the institution’s annual meetings (along with the World Bank) held in Washington in early October. The two indices reveal a number of interesting trends that should be of interest to Pakistan’s policymakers.

The first, of course, is the constant increase in prices over the last four years. The indices did not move up and down as commodity prices have done in the past, reflecting short-term developments. They have been constantly pointing upwards. The second is the steeper incline in the trend-line for energy compared to that for food. This is interesting since the current mix of energy is dominated by oil which is a fast depleting resource. Compared to oil, food is a constantly renewable resource for as long as the world does not run out of fresh water.

The third interesting trend is that both indices reached their peaks in July 2008, before the financial meltdown in the United States began to affect global demand. Until then, the increase in demand in such rapidly growing economies as Brazil, Russia, India and China – the BRIC nations – was the primary factor behind the relentless increase in commodity prices.

In looking at the future, the forecasters at the IMF see slight reductions in the levels of the two increases in the next nine months. As most economists know, future of commodity prices is very hard to predict which is one reason why the IMF’s projections don’t extend beyond July 2009. By then, the organisation’s experts expect the index for food prices to decline by 10 per cent from its peak in July 2008, and that of energy by 7.5 per cent. In other words, the energy price index is likely to be much more “sticky” than the food index. The main conclusion to be drawn from looking at these two indices is that the world needs to come to terms to a significant paradigm shift in the terms of trade between the products produced by different sectors of the global economy.

Some sixty years ago when development economics began to develop as a separate discipline, the prevailing consensus was that the terms of trade would always move in favour of the manufacturing sector. It was that belief that led most developing countries to adopt “import substitution” as the strategy for growth. The Soviet Union led the way and was followed most prominently by India and most countries of Latin America. This approach produced rapid industrialisation but it also brought about isolation from the global economy that was dominated in the second half of the 20th century by North America, Western Europe and Japan.

However what came to be known as the miracle economies of East Asia, adopted an entirely different stance towards growth. Rather than create high walls of tariff as was done by the “import substituting countries”, the East Asians sought closer trading relations with the industrial world. This they did by “picking the winners” and concentrating the attention of both the state and the private sector on their development.

South Korea chose the products of heavy industry – ship building in particular – while Taiwan concentrated on electronics. Both succeeded enormously. South Korea’s heavy industrial base was to turn the country into a major exporter of not only ships but also automobiles and large screen television sets. The Taiwanese carved a prominent market share first in computer parts and later in such exotic areas as nano-technology.

In thinking about the economic future, I believe that we should concentrate on the long-term trends and not be deflected by short-term developments. The current economic crisis in the financial markets of the developed countries and the way it has begun to affect the real sector will lead to many changes in the structure of the global economic system. That said, we should continue to plan for Pakistan’s future by concentrating on the development of the sectors in which the country has comparative advantage. All indications suggest that Islamabad should focus on using agriculture to pull the economy out of its current critical situation and have the sector provide inflation-reducing supplies for domestic consumption and for earning exports. Were that to happen it would be real paradigm shift in development thinking.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.