WHEN the financial crisis unravelled in the West, leading to a global economic meltdown in the last quarter of 2008, many policy-makers and observers in India were confident that the country – growing at a frenzied nine-plus per cent growth rate over the past four years – would be insulated from the storm.

WHEN the financial crisis unravelled in the West, leading to a global economic meltdown in the last quarter of 2008, many policy-makers and observers in India were confident that the country – growing at a frenzied nine-plus per cent growth rate over the past four years – would be insulated from the storm.

But the initial over-confidence has given way as the enormity of the global crisis has sunk in. Despite strong first-half performance in fiscal 2008-09 (GDP grew by 7.6 per cent in the second-quarter of the fiscal, which ends on March 31, 2009), the government has been forced to admit that India will inevitably be dragged into the vortex of the global slowdown.

There are enough indications of a looming crisis: economic growth has slowed down and many are slashing projections from the earlier 7.5 to 8.0 per cent to even below seven per cent; exports have for the first time since 2002 recorded negative growth; and the manufacturing witnessed negative growth for the first time in 15 years. Worse, in fiscal 2009-10, growth is expected to be in the range of five per cent.

For the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, the economic slowdown – resulting in tens of thousands of job losses in factories and even IT and ITeS units – has come at the most inopportune time. General elections are due to be held in April/May this year, with the election schedule to be announced over the next few weeks.

Once the election dates are announced by the Chief Election Commission, the government would be in no position to announce any sops for the electorate, as it would be tantamount to violating the norms.

Most of the other leading economies of the world have been unveiling fiscal stimulus plans to overcome the meltdown. The US, for instance, has unveiled a nearly $800 billion plan for 2009 and 2010. The European Union has a $270 billion plan, while China has come out with a $175 billion plan. Even Japan has announced a $25 billion fiscal stimulus, which the government hopes will pull it out of the recession.

India announced the first set of measures to stimulate demand in the economy in December, 2008. And on January 2, it followed it up with the second set of measures aimed at boosting demand in the economy. The $8 billion fiscal stimulus adds up to just 0.8 per cent of the GDP, as against 5.4 per cent of the GDP announced by the US government, 4.5 per cent of GDP by China and 1.5 per cent by the European Union.

* * * * *

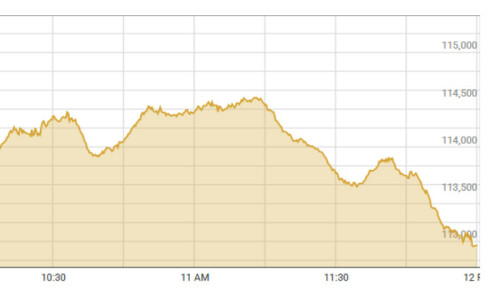

THE stock markets responded positively to the second set of fiscal stimulus unveiled by the government in the New Year. The Sensex, the benchmark index on the Bombay Stock Exchange, flared by 3.2 per cent on Monday last, the first working day after the announcement of the fiscal stimulus.

The index had undergone a severe mauling in 2008, shedding 52 per cent during the year, its biggest-ever drop. Much of the loss was triggered off by massive selling by foreign institutional investors (FIIs), who pulled out funds to repatriate it to their home countries. However, since the indices plunged to record lows in October, the markets have perked up, gaining over 30 per cent in the last three months.

Most of ingredients in the two fiscal stimulus packages were contributed by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country’s central bank. The bank, which had been raising interest rates for the past four and a half years – it had increased the benchmark repo (repurchase rate) from six per cent in April 2004 to nine per cent in October 2008 – made a U-turn in the third-quarter of the current fiscal.

On January 2, the RBI lowered the repo by a percentage to 5.5 per cent, slashed the reverse repo rate also by a percentage (to four per cent) and also the cash reserve ratio (CRR) by half a per cent to five per cent. The central bank believes the move would inject an additional liquidity of $2.1 billion into the economy.

“It is expected that the reduction in the policy interest rates and the CRR will further enable banks to provide credit for productive purposes at appropriate interest rates,” the RBI said while announcing the cuts. “The fundamentals of our economy continue to be strong. Once the crisis is behind us, and calm and confidence are restored in the global markets, economic activity in India would recover sharply. But a period of painful adjustment is inevitable.”

The RBI has revised the repo rate four times since October, slashing it by 350 basis points. It has also cut the CRR by four per cent and cut the reverse repo rate by two per cent. But despite prodding from the government, banks (including state-owned ones) have been reluctant to come out with matching rate cuts. A few banks have reduced interest rates by around 1.5 per cent since October.

Analysts expect the central bank to go in for a further cut of around 150 basis points over the coming two quarters.

* * * * *

ONE of the main factors that forced the RBI to raise interest rates last year was the fear of inflation. After staying within the single-digit level for the past four years, inflation touched the double-digit mark last year, peaking at 12.91 per cent in August, following the sharp spurt in international oil prices.

But despite the RBI’s moves, inflation failed to react to the hike in interest rates. However, the slowdown in the global economy – which also led to a sharp decline in oil prices – resulted in a lowering of the wholesale price index (WPI) in India. Inflation was down to 6.38 per cent on December 20.

Ironically, the RBI and the Indian government are now battling the impact of the global slowdown and are slashing interest rates, hoping to encourage public spending and boost consumption.

The UPA government, which reduced the price of petrol and diesel by Rs5 and Rs2 a litre respectively in December, now plans a further steeper cut just before the announcement of the election schedule. Murli Deora, the petroleum minister, has indicated that the government would announce a rate-cut soon.

The government has also been unveiling several sops for the corporate sector. In the second fiscal stimulus package, it raised the overseas investment limit for rupee corporate bonds from $6 billion to $15 billion. It also did away with the ceiling on interest rates that companies can pay for their overseas borrowings till June 30.

In the December package, the government had gone in for a four per cent reduction in excise duties for all goods except petroleum products. It had also offered a slew of incentives to exporters, raising fears abroad of subsidising exports. In January, it decided to re-impose special import duty on cement and some steel products.

The two stimulus packages are likely to deepen the fiscal deficit further. The government had budged for a fiscal deficit of 2.5 per cent of GDP, but spending on a host of schemes had resulted in its growing to 3.3 per cent, even before the fiscal stimulus packages were unveiled.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, a close aide of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, and deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, believes these fiscal measures would ensure India stayed on the growth path in the current fiscal and in the next one. He estimates a GDP growth rate of seven per cent for the financial year ending March 31, 2009.

But Ahluwalia, who together with Singh and former finance minister (and now home minister) P. Chidambara, is the key financial policymaker, admits that it is impossible to insulate the country completely from a major downturn in the world economy.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.