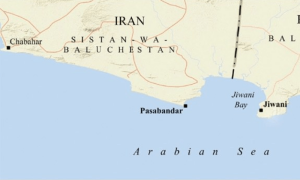

KARACHI: Two months into Pakistan's blockade on Nato supplies crossing into Afghanistan, thousands of trucks are crowding the port in Karachi where drivers, fed up with waiting, are starting to desert.

For a month, directors of transport companies, drivers and their helpers hung around patiently, buoyed by rumours of an imminent reopening of the border, shut after US air strikes killed 24 Pakistani soldiers on November 26.

But the botched raids snowballed into the biggest disaster in Pakistani-US relations since the 2001 American invasion began after the 9/11 attacks.

Two months on, Pakistan is still reviewing the relationship and no one knows when the border will reopen, through which passes 25 per cent of the supplies needed by the 130,000 foreign troops under US command in landlocked Afghanistan.

Fed up, running out of money and missing their families, many of the drivers have since abandoned their trucks and returned to their homes, often in Pakistan's troubled northwestern areas near the Afghan border.

“They had no more money in the end so they left one helper with their vehicle for security and care, and went back to their families,” said Mohammad Saleh Afridi, vice chairman of the All Pakistan Oil Tankers Association.

He says more than a thousand trucks are stranded in Karachi. In addition, there are containers and military vehicles —about 5,000 according to a count provided by the authorities in early January.

Since then, more have arrived by boat. Hundreds of oil tankers are filling huge car parks by the sea.

“Most of the tankers are loaded with fuel, so helpers have to look after them to avoid looting,” said Afridi.

For years, drivers of Nato trucks and tankers have been frontline victims of the troubled Pakistani-US relationship.

Seen as traitors by extremists, considered open game by bandits and now doing without their salaries because the relationship has taken a nose dive, the drivers have been the unwitting pawns trapped in the middle.

Gul Khan, who has eight oil tankers supplying Nato, confirms that drivers are leaving Karachi. “We're worried, we can be attacked,” he told AFP.

In 2008, attacks on trucks began to rise as Pakistani government forces became increasingly locked in trying to put down a Taliban insurgency and al Qaeda-linked militants went on bombing rampages across the country.

Are the attack carried out by Taliban, bandits, rival trucking companies or simply as an insurance scam or as a means for the authorities to put pressure on Nato? The theories are endless, but the proof is lacking.

Working for Nato is also a serious handicap in a society fed up with the US alliance that many blame for violence sweeping the country.

“Nobody wants to see us any more,” said Khan. “(Roadside) hotels and restaurants are afraid of attacks and don't allow us to stop by anymore. Police are taking lots of bribes —it wasn't like that before, three years ago for example —and tell us to stop working for Nato.”And the trouble doesn't stop at the border.

“In Afghanistan, we're attacked very often and Afghan police insult us, they shout: 'Shame on you, you're working for American infidels!'”Some drivers are happy about the blockade.

“If it closes down for good, that's all right. It's not a problem for us. At least we won't get abused,” said Rozi Jan, parked near the port.

But like others, many of whom come from Pakistan's lawless tribal belt, he will start working again when the border reopens.

“There are no jobs in our villages. Being a driver is the only solution to feed our families,” said Mohammad Ayub, 33.

A driver for Nato earn 30,000 rupees ($330) a month, then an additional 30,000 rupees per trip to Afghanistan, which they can do once or twice a month, far more than the average salary of 7,000 rupees in Pakistan.

When the war began in late 2001, the job was easy, but not anymore.

“You could make loads of money, so we borrowed money to buy trucks. But now everything is expensive and difficult,” said Khan, who is paying back at 15 per cent a 2.5 million rupee ($27,700) debt.

In 10 years, 10 of his drivers have been killed and 12 of his trucks destroyed. He hopes one day to get out of the spiral of debt and get a new job.

“Every Pakistani who's not involved in the business is against it,” he said.