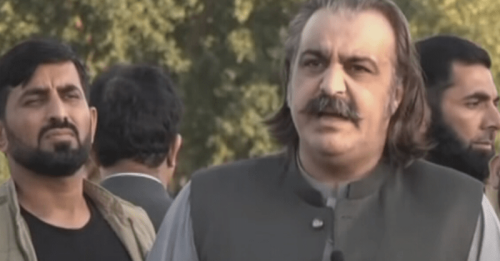

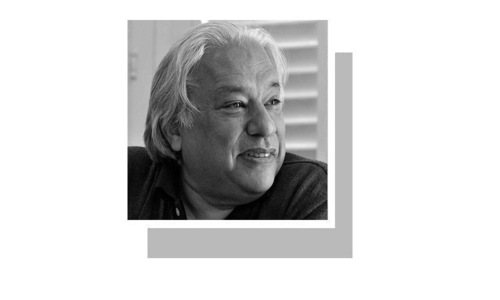

KARACHI: Some interesting as well as oft-repeated points were raised during an interactive discussion titled ‘The Revival of Pakistani Cinema’ between ad and video filmmaker Asim Raza, actress and director Zeba Bakhtiar and exhibitor and distributor of films Nadeem Madviwalla at T2F on Friday evening.

The first question put to the panellists by the moderator Meher Jaffri was on the kind of stories that Pakistani films should have.

Bakhtiar said they should reflect the aspiration of Pakistani people and have positive elements in them. She said the kind of society we lived in needed positive tales told with dignity. For that, she argued, we didn’t have to look towards India, because sufficient material could be had from our own literature and poetry. Raza echoed what Bakhtiar had said and added that romance-based stories could be written, not necessarily in the typical sense but the kind that Merchant-Ivory or Guru Dutt used to show in their films. They should have substance and provide the right kind of balance.

Mandviwalla took a different route. He informed the audience that since 2007 a change had occurred. Before that, beginning from the 1980s, there used to be gandasa films, makers of which thought that that was the kind of material that sold, even if one out of ten of such movies ran successfully. He said from that time till 2007 there was a huge gap and the entire infrastructure of the film industry collapsed. Today’s audience was different. He said now that he ran foreign films at his cinemas people teased him that he’s making money.

Mandviwalla likened films to a factory. “You produce a film and take it to a retail shop. You have to have a minimum base. You have to go according to the demand of the market.”

He remarked that Pakistani filmmakers made films for Pakistan, whereas they should make them for the international market.

He gave the example of Shoaib Mansoor’s Khuda Ke Liyey and Bol which made money from the Indian circuit.

On the question of the financial aspect of movie making, Bakhtiar said it was important because one needed to get an investor to make a film and the investor than had to make money out of it. Some investors, she said, had been using the profession for money laundering. She insisted that at the end of the day filmmaking was a business.

Raza pointed out that youngsters took filmmaking as a hobby. They must consider it a profession. Reflecting on how society saw filmmakers, he said there was a time when people would meet him and upon knowing that he was a filmmaker would ask what else he did, because they didn’t think movie making was a profession. As for artistic expression, he said in India they had different categories and among other genres there was meant for substantial cinema. Anything made in an intelligent and interesting manner should work. He said anyone who made a film for personal expression shouldn’t expect the audience to like it no matter what.

When the moderator asked Raza why people intended to throng to atrium mall to see Ranbir Kapoor’s latest film Barfi whereas the situation at Nishat cinema was different Raza said we needed to educate people and engage them. There was a time when an Ashfaq Ahmed play would glue families to their TV sets, but nowadays Star Plus soaps did that. He reckoned the environment that cine-goers had at cineplexes made them go there.

Mandviwalla differed with Raza and said all over the world there were rights for theatrical releases, for DVDs, and for satellite TV, but in Pakistan there were only theatrical rights. “Pakistan’s is one hundred per cent pirated market.” He said if one was getting to see free DVDs and free films on cable TV, then why would one bother to spend money. He informed the audience that India had totally followed the Hollywood model which was based on one-week recovery, that is, they made a certain target for the first week of the film’s release and built up on that. He said in Pakistan we were class conscious, not quality conscious. In India, they catered for three tiers of market — high-end, middle-end and low-end. In Pakistan we were catering to the high-end market alone and were unable to improve the low-end one.

Mandviwalla lamented that we were a seriously strange society. We let people snatch our mobile phones worth Rs5,000 and kill us, but never bothered when our intellectual property was stolen. He said the debate why we weren’t making quality films was futile because we weren’t making any films. He insisted that Shoaib Mansoor was an exception, not a rule, because had he been the latter, people would have followed him.

On the issue of pre-production hassles, Bakhtiar said there were no qualified screenplay writer, no production designer, no makeup artist and no choreographer in Pakistan. Apart from that, she commented we needed to create our own heroes. She said our girls and boys were more good-looking than Indian actors but bad lighting and makeup made them look ordinary on screen.

Raza agreed and said we needed to give respect to the technical staff involved in filmmaking. Everybody in Pakistan wanted to become a director, he lamented.

Replying to the question of formal training for acting, Bakhtiar in a lighter vein said every Pakistani woman knew how to act, and one day she decided that she should get paid for it. With regard to the issue of the censor board, Mandviwalla narrated a few amusing incidents. He then apprised the audience that after the 18th amendment it was a provincial matter; but Sindh and Punjab were yet to have their boards. To date films went to Islamabad for certification where someone did the needful but he couldn’t watch the films because they were a provincial subject.

After the discussion the floor was opened to the public for a question-answer session.