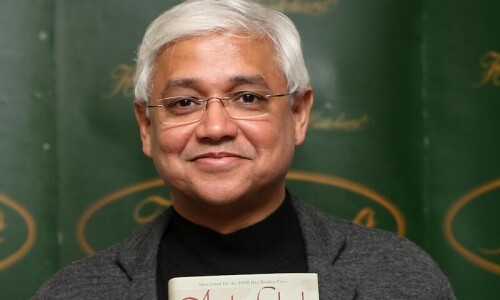

Two days ago, I received a message from a friend in Lahore that Intizar sahib was critically ill. His kidneys had failed and he had pneumonia. My heart sank; I prayed for a miracle. The sad news reached me as I was restlessly skimming through the pictures of my recent trip to Lahore, two months ago, in November.

It was five days packed with literary events; there were lunches, dinners and teas with Intizar sahib. He was impeccably dressed, beaming, twinkling, and narrating stories with inimitable flair.

Take a look: Writers, fans mourn the passing of literary giant Intizar Hussain

Together, we discussed Urdu legends Muhammad Hasan Askari and Ghalib. I took too many pictures; he scolded me affectionately. I couldn’t stop recording those precious moments.

I was in immense awe of the enormous vista his writing spanned. Shining prose flowed from his pen in seemingly effortless strokes. A style that is close to speech but distinguished by its ability to grapple complexities of literariness with deceptive simplicity.

I was introduced to Intizar sahib’s work rather early because of my upbringing in Urdu’s jadidiyat (modernist) milieu.

As a young girl, I was perplexed by modernist Urdu fiction and struggled to empathise with stories that seemed to have no plot. But Intizar sahib’s fiction stood out to me in its starkness.

His narrative had timelessness to it. It was free; unshackled from ideological weight. It was trying to make sense of the present.

For me, no other writer has approached the Partition the way Intizar Husain did in his writings; his connection with the past is organic.

His collection Satvan Dar (Seventh Door) presented stories of unfulfilled longing. This complex longing has many levels: it is longing for a lost world; it is a desire for imaginative prowess; for blossoming of creativity in an alien environment. He desired to retrieve the past by creating a mythical, parallel world.

He successfully used allegories to fashion narratives that simultaneously worked on different levels. In creating a mythic world, Intizar sahib explored the treasure house of Buddhist and Hindu mythology.

Mornamah (Chronicle of Peacocks), a story written after India and Pakistan carried out nuclear testing, is a great example of his successful weaving of mythology to present circumstances.

More recently, he tried his hand at memoir writing; an entirely different engagement with the reality of the past. Chiraghon ka dhuan (Smoke of clay lamps) evokes memories of the heady rush on the creation of Pakistan.

It describes the excitement felt by young Intizar Husain and his peers when they met at Lahore's Pak Tea House and participated in the epic-historic moment.

He details the eager discussions on literature and poetry that went deep into the night. The pain of separation sinks in after the euphoria has evaporated.

I marvel at how multifaceted his writing is. He inhabited many worlds but never lost touch with reality.

In the past few years, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to discuss my own work with him. Most recent is the November 30 column in Express Lahore that he wrote on my recent research.

Like his writings about the past, Intizar sahib is more genuinely alive in the present, in the chambers of our hearts.

Read all Dawn columns by Intizar Husain here.