The bloodbath in Karachi continues. The death toll in the last week alone has reached over 100. A glance at the online tally of dead bodies in Karachi leaves not much room for hope in Pakistan’s largest city. The citizens appear helpless, the government looks impotent, and the future looks grimmer by the day.

While the resurgence of violence in Karachi is a recent phenomenon, the rest of Pakistan had been engulfed in senseless violence since 2003. No fewer than 36,000 Pakistanis have died in violent deaths in the past eight years, making Pakistan the hotbed of religious, political, and ethnic violence.

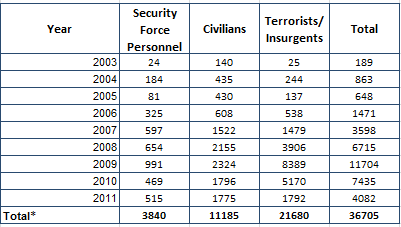

Whereas 189 fell victim to violent death in 2003, the number of violent deaths swelled to 11,704 during 2009. Though the number of deaths dropped significantly in 2010, it appears that violence is resurging again in 2011.

Not all victims of the senseless violence are civilians or the security force personnel. In fact terrorists and insurgents constitute the largest group of those who died a violent death in Pakistan. Since 2003, 21,680 terrorists have been reportedly killed in Pakistan. Surprisingly, Pakistan is no safer today even after such a massive death toll has been exalted on the perpetrators of violence.

Many in Pakistan and abroad see these numbers with suspicion. First, the very number (21,680) appears grossly exaggerated. Even if the proclaimed number of terrorists killed is around 22,000, one cannot ascertain how many of those who were labelled as terrorists were in fact collateral damage, i.e., innocent civilians ending up at the wrong place at the wrong time.

The recent claims by the US authorities that no civilian has died in recent drone attacks in Pakistan is one such example of an engineered narrative of war that tries to paint death and destruction in a clinically humane way by portraying all victims as murderous terrorists. Admitting death of bystanders, school children, and women would present an uglier, yet a true and perhaps unacceptable picture of war.

The policy to paint all dead as terrorists inflates the number of terrorist deaths and underreports the death of civilians. Even with the deflated stats, almost 11,200 civilians and 3,840 security personnel have died in Pakistan since 2003. For a nation that is not in a state of war with a foreign power, such a large number of violent deaths are indicative of a civil war.

While Pakistan is not the only country facing domestic discord and extreme violence, it has though evolved into one of the most violent places in the world. A comparison with other neighbouring states in South Asia suggests that violent deaths in Pakistan now account for 79 per cent of all violent deaths in the region. In 2005 alone, violence in Pakistan accounted for merely 10 per cent of the violent deaths in South Asia.

As the violence escalated in Pakistan in the recent past, the number of civilians and security force personnel who lost their lives to extremist violence declined relative to terrorist deaths. In 2003, for instance, 6.6 civilians and security force personnel died in extremist violence for each dead terrorist. This ratio fell below 1 for 2008, 2009, and 2010 as a result of military operations in FATA and Khyber Pukhtoonwa against militants. However, the spike in civilian deaths in 2011 has reversed the trend suggesting more dead civilians and security personnel than the militants

The last few years of violence in Pakistan is similar to what had transpired in Sri Lanka. The Sri Lankan government in 2009 responded with all its might to tackle Tamil Tigers who have been orchestrating a militant separatist campaign. In 2009 alone, 11,000 civilians and 1,300 security force personnel lost their lives due to violence. In the end, the Sri Lankan government was able to destroy the Tamil Tigers and kill their leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran. While the Sri Lankan example of successfully tackling the extremists sounds optimistic, the militancy in Pakistan is much more complicated and multifaceted to be dealt decisively in the short term.

*This is the first half of a three-part article.

Murtaza Haider, Ph.D. is the Associate Dean of research and graduate programs at the Ted Rogers School of Management at Ryerson University in Toronto. He can be reached by email at murtaza.haider@ryerson.ca

The views expressed by this blogger and in the following reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Dawn Media Group.