Drones: choosing between droning on and understanding

By Ejaz Haider

One of the basic requirements of fighting wars and the many battles that make up a war is to gain asymmetric advantage over the enemy.

Put in English, if you find yourself in a fair fight, you didn’t plan well.

Winning is about unfair advantage at four levels – political, strategic, theatre, and tactical – of any conflict.

When David faced Goliath, a straight contest would have got David killed. His asymmetric advantage lay in deception, speed and surprise.

That’s where the slingshot came in, not only neutralising Goliath’s advantage but felling him. The history of warfare is the story of unfair advantage.

Today’s wars and its battlefields are complex and non-linear, but the basic principles remain unchanged. Non-state actors have introduced the suicide bomber, raising the cost for the state by upending the basic principle of security, i.e., self-preservation.

States, on their part, have learned that superior force in this contest with elusive enemies is not much use.

Corollary: develop and utilise technologies that are accurate, discriminatory and, more crucially, can be embedded in a C4I2 (command, control, communications, computing, intelligence and information) process for greater precision.

The objective: preempt the enemy and strike deftly.

This is where drones, remotely-piloted vehicles, come in. They have become the most controversial platform over the last decade, flying and striking stealthily and, for the most part, cleanly and precisely.

The debate has two extreme ends: the absolutists who oppose their use unconditionally and the proponents who advocate their enhanced use equally unconditionally. The facts of drones use, as always, lie somewhere between these extremes.

The issue – or as some would like to term it, problem – has to be debated at three levels: technology, operations and law. Let’s consider them in that order.

First, drones aren’t just used to kill people. The technology has multiple uses, most of them in fact benign. While Amazon’s Octocopter package delivery project may still be in the future, drones are already being used in agriculture, search and rescue, 3-D mapping, geological surveys et cetera.

Corollary: the technology is here to stay. In 2005, around 40 countries possessed drones of varying capabilities. By 2012, this number had gone up to 75. It includes Pakistan.

Corollary 2: an idea cannot be dis-invented, though it can be controlled. We face the same problem with nuclear, chemical and biological substances.

Corollary 3: control, legal and normative, always succeeds technology. It cannot precede it. That’s an historical fact. Just because some of us don’t like drones is unlikely to reverse the obvious logic of this truism.

The next level is operations and by operations we mean their military-intelligence role, since that’s the only use that seems to make news.

In their military role, armed drones are used for long-duration surveillance, close air support, force protection strikes and ground attack. Funnily, while the use of drones in all these roles is bitterly criticised, all of these functions were performed by conventional aerial platforms which were, and remain, far less accurate and precise than the drones.

Drones can be used for missions round the clock, and their use has several advantages which make them extremely attractive to intelligence operators as well as field commanders.

The cost per flight hour is very low compared to fighter aircraft.

Cost estimates put out by the US Air Force show that the cost per flight hour for an F-15E Strike Eagle is USD 36,343, USD 22,514 for an F-16C Viper and USD 17,716 for an A-10C. Compared with this, the cost per flight hour of Predators and Reapers is USD 3,679 and USD 4,762, respectively.

Drones also have greater loiter time for ground intelligence.

A Reaper can stay up in the air for 14 hours. They are more precise and accurate. Pilots are not exposed to danger through air-to-air and ground-to-air attacks. The platform saves ground troops from entering hostile environments and drones can hit targets in inaccessible areas, making using ground troops irrelevant. That itself is a very tempting factor at various levels: no attack and extrication plans, no logistics headaches and no medevac problems.

Additionally, the inability of the enemy to kill the drones, the stealth with which they can strike multiple times instils fear in an elusive enemy, allows discriminate strikes against targets that are tightly coupled with the population, restricts the enemy’s freedom of movement and action, denies him assembly, makes electronic communications difficult, sows distrust among enemy cadres and degrades leadership, personnel and material through personality and signature strikes.

In short, drones are a dream aerial platform for military commanders fighting elusive enemies in areas where the zones of war and peace cannot be separated.

So, why is their use so controversial?

Part of the answer lies in the fact that the platform has been used very effectively in wars that are looked upon as imperial in nature. The issue at that level has more to do with the legitimacy of America’s war on terror and its narrative than the use of drones per se. However, the newness of the platform and its stealth make it menacing and sinister in an Orwellian way. This description is not entirely wrong but it misses the point that intelligence agencies are now using other technologies (and hacking techniques) that are no less Orwellian.

As for the much-hyped ‘collateral damage’ allegation, while drones can and have killed people other than terrorists, the fact is that all other known aerial and ground weapon systems and platforms are far less accurate than the weapons on the Predator and its advanced cousin, the Reaper.

Finally, we have the legal level. It’s also the most troublesome.

The problems of law relate to consent, self-defence, imminence of threat (the moral hazard of preemption), organisation (what groups or people can be targeted?), intensity of hostilities, targeting rules, transparency et cetera. Each of these problems emanates from legal principles that have become customary practice and are recognized as such in the body of law as it exists (lex lata).

What jurists fear, and this fear has been expressed in multiple high-end reports, is that the US is making an effort to change the practice of existing law in favour of lex ferenda (future law) which does not obtain at this point.

This is, and was, inevitable. In situations where the nature of conflict has changed and remains in a state of flux, there is always tension between law and force.

The existing body of laws dealing with self-defence at one end (Article 51 of the UN Charter) and non-use of force at the other (Article 2 (4) of the Charter) presupposed inter-state conflict. Even the idea of preemption related to a recognised way of fighting and some determination of the principle of imminence.

That situation has changed. Self-defence, incorporating the idea of preemption, now focuses on the highly controversial concept of anticipatory self-defence with all its attendant moral hazard.

As jurists have pointed out, this throws the problem back to the pre-Charter days, to what is termed as the Caroline incident.

The precise threshold for determining imminence is a subject of dispute and will always remain so. And it becomes even more problematic when preemption is conflated with prevention, as happened in the Caroline case or when the Israeli jets struck the reactor in Iraq, to mention just two examples.

This is how Ben Emmerson put it in his report to the UN:

This, then, is the bird’s-eye view of drones and drones use. The technology will only move further, its uses will multiply, in many cases drones will remain the preferred option as a weapon platform and law will have to keep pace with the technological and operational contours of these pilotless birds.

It will become easier to figure out a legal-normative framework for their weaponised use when more states have developed armed drones with beyond-line-of-sight capability.

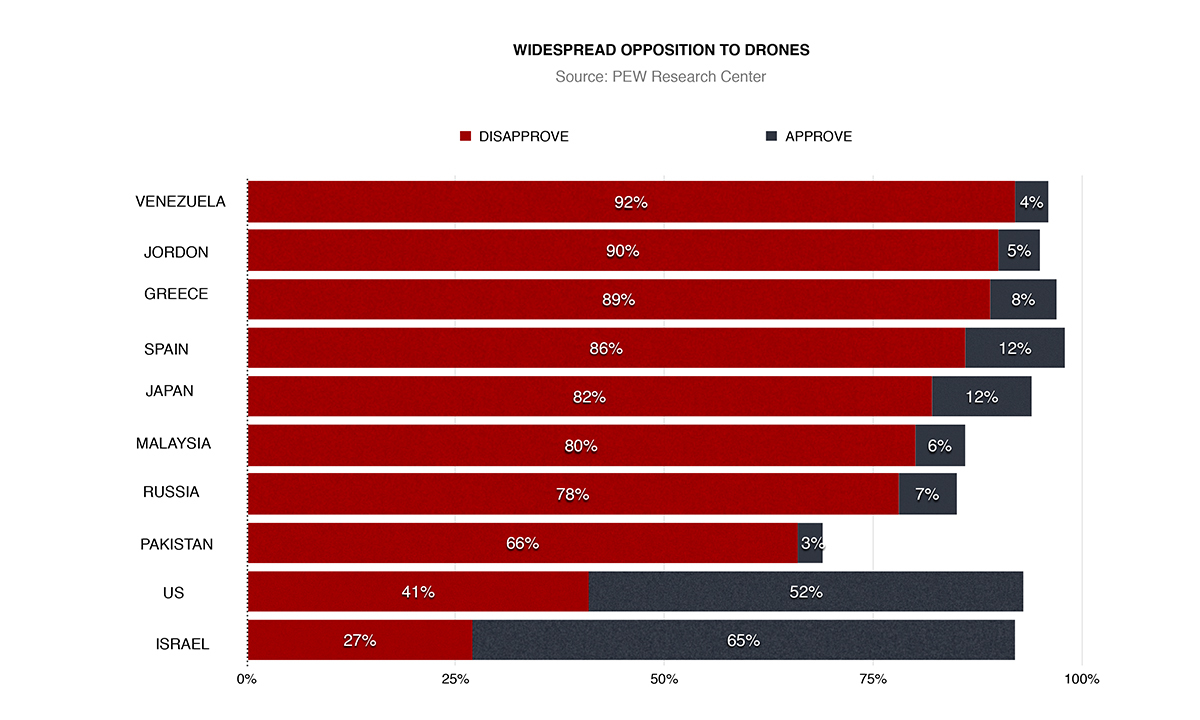

There has been noteworthy increase in public disapproval of drones since 2013. American’s own disapproval of missile strikes has grown 11 per cent in the past year.

Israel, Kenya and the US are the only nations polled where at least half of the public supports drone strikes.

Women are more likely than men to oppose drone strikes in America whereas young Americans disapprove it more than the older generation.

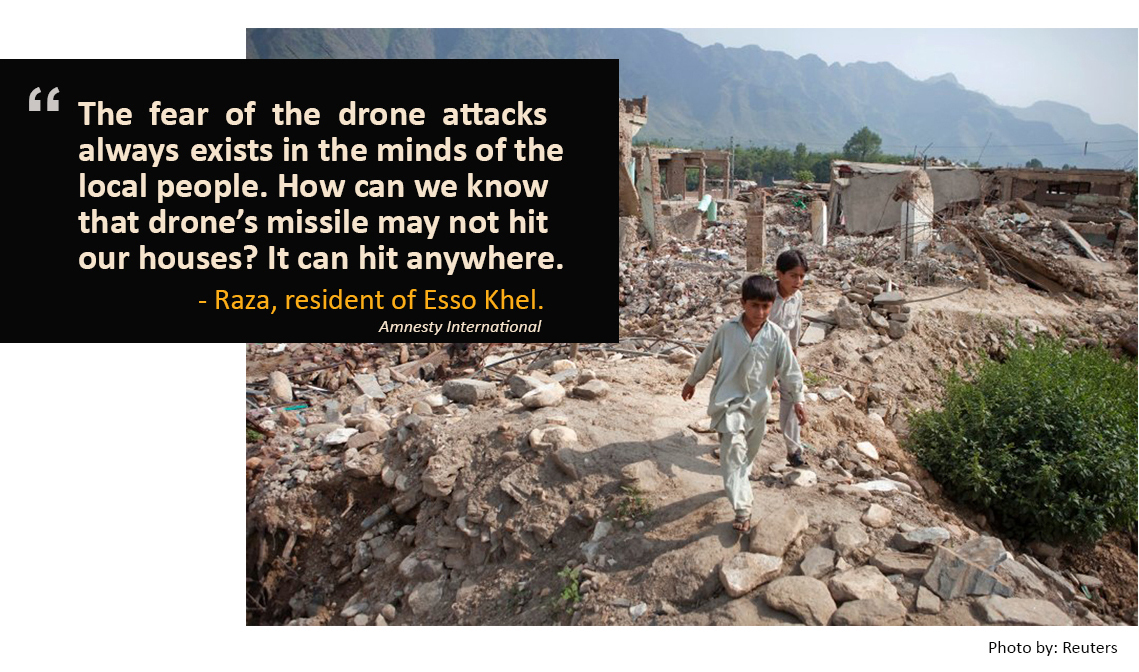

It is pertinent to mention here that Pakistan was the only country surveyed where the US drone strikes take place, with the other two countries being Yemen and Somalia.