Reviewed by Mohsin Siddiqui

The disadvantage of reading Karachi: Our Stories in Our Words on a trans-continental flight is that it is next-to-impossible to rid oneself of the book in any sort of permanent way. Eager flight attendants scurry down the length of the cabin, bearing it aloft in triumph, reminding you that you “left something behind”.

Why, yes. Yes I did. Curses upon you, flight crew, and upon your efficiency too. If indeed karma exists, I can assure you, payback will be severe (and drawn-out, if I have anything to say about it).

The blurb at the back of this collection reads as follows: “There are stories of kindness and empathy. And there are themes of deep income disparity and social justice. There is nostalgia for a time gone by in Karachi, a new awareness of its past history, a love of the beach and the sea. There is deep pain in these stories — of the loss of loved ones, of violence and murder and target killings — and a real sense of belief and hope for a better future.” This should probably have been my first warning.

Of the 99 stories printed under the aegis of Maniza Naqvi’s editorial eye, approximately 95 of them deal with all of the above themes, with the exception of “a real sense of belief and hope for a better future.” Quite frankly, were a reader to assume these stories as a representative baseline for Karachi’s future, it wouldn’t seem to have much of one, other than as a charred apocalyptic wasteland.

After reading this collection of short stories, you may well find yourself stunned at the fact that any of the 18 million-odd residents of Karachi are still alive and whole. By story number 16, I was trying to recall whether my normal routes through the city were as perpetually flooded with rivers of blood and a sampling of charred body-parts as the assorted authors in this collection would have one believe. By story 25, I was reaching into my carry-on luggage in the vain hopes of finding anti-depressants hidden away somewhere. And by story 68, I was cringing, hoping that the nice man at the immigration counter wouldn’t ask me about “how things are in Pakistan,” because I would be forced to say “Utterly abysmal. Just open up any page in this book and see for yourself.”The tales in Karachi were solicited via a newspaper placement, and it shows. With the exception of a handful of sharp, evocative accounts (‘The Reprieve: No Bikini but Plenty of Attitude’ comes to mind), they are all remarkably puerile. Perhaps the aim of the collection was to be a real or accurate chronicle of how everyday Karachiites experience the city. But if editorial curatorship means anything at all, I suspect the same quality of work could have been directly solicited from a group of teenagers’ college application essays.

There are melodramatic tales of repentant criminals whose only exculpation comes from suicide (see ‘The Unknown Man’), of ill-done-by office peons whose cruel bureaucrat bosses, not content with verbal abuse also steal their prized possessions and get their just desserts (as per ‘The Heirloom,’ such behaviour is rewarded with death-by-suicide-bomber). In ‘Murad Ali,’ a rich,

arrogant man eats crow when the life of his son is saved by the same person he unjustly accuses of being a grifter (suffice it to say that the last sentences here include: “God has made you a comfort for humanity,” and “I was intoxicated by my wealth and was devoid of the passion of human kindness”).

At the risk of glossing over the occasional story that is genuinely evocative in some way, rather than pedantic or a morality tale with all the finesse and subtlety of the explosions it describes, it is hard to read this collection of tales and not be affected by it — and not in a good way.

Perhaps the intent of the collection was to show what newspaper headlines constantly trumpet about Karachi and its inhabitants, that mysterious “resilience” we all apparently possess in spades. Perhaps there was difficulty in translating all these stories from the various languages in which they were submitted originally. Maybe the only things that people genuinely consider worth writing about when it comes to Karachi are (1) bombs, (2) muggings, (3) assassinations, (4) the downtrodden poor, (4) more bombs, and (5) random shootings.

This is understandable — Karachi is not a safe city. Nor is it a fair city; like any other major metropolis, it contains multitudes. There are the über-rich and the horrifyingly poor. There are businessmen and doctors and VIP cavalcades and careless drivers; there are people who cruise around in Toyota Prados and those who make death-defying leaps off of a bus. But surely, in the flood of submissions received, there had to be more than a handful that dealt with something other than a poor innocent having his or her limbs blown off by a random explosion.

The stories which are clearly autobiographical are perhaps the most interesting; their sepia-tinted prose is nostalgic without becoming twee — much like a slightly dotty relative’s meanderings, there is charm and the hint of accessibility and experience within these stories.

But there is something almost offensive about the disconnect between Naqvi’s introduction to Karachi and the actual contents of the volume. I defy anyone to read through all 99 of these stories and say “Yes, I can see that there’s a sense of hope.” ‘Things explode in Karachi,’ is the sub-text with which we are presented, ‘oh, and there are a lot of bad people who do bad things to good people’. Yes, of course there are. But there are good things too, and perhaps it begs the question of whether the quantity of responses to the call for stories led to a dismissal of their quality, or whether the entire populace of budding writers in Karachi have no view on their city other than one that would make 1970s Beirut seem like a spa holiday in the Maldives.

The fact is that whether due to issues with translation, poor quality of submissions, or just a vigorous abandonment of editorial discretion, Karachi winds up being far less than it could be. Instead of capturing the genuine multiplicity of one of the world’s largest cities — and let the record show that I’m hardly a cheerleader for the wonders of this megapolis — this anthology is flat and one-dimensional.

There are only so many ‘protagonist was caught in a terrible bomb blast’ stories that can — or should — be included in a single volume, and it seems that the editorial team responsible for Karachi have decided, for reasons that will likely remain forever unclear, to toss them all in here for good measure. There is a comment to be made here about the proverbial kitchen sink, but one fears that said fixture is already present somewhere in these stories, presumably filled to overflowing with severed limbs and starving beggar-children.

Fundamentally, though, the issue here is not even about the quality of the fiction itself, although that is — much like the many catastrophes it describes — hard to ignore. It is about the fact that with what are possibly the best intentions in the world, the stories collated in Karachi fail to land with any significance. People cannot be faulted or judged for the topic (please note the singular) about which they write, but it is likely fair to assume that somewhere in the heap of articles sent in to Oxford University Press for this book, there must have been more than a handful that capture the real “resilience” of Karachi and its denizens. Sadly, that is lost in a morass of borderline-farcical Grand Guignol fiction that demonstrates a great deal of emotional span, but very little depth.

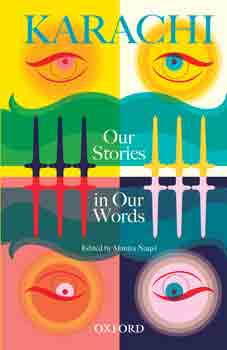

Karachi: Our Stories in Our Words

(Short stories)

Edited by Maniza Naqvi

OxfordUniversity Press, Karachi

ISBN 9780199068517

360pp.