This past week I have seen the world from a subterranean space, where a number of diligent young men spend the better part of the day printing images and text neatly composed and designed. This is followed by packing it all away in custom-printed envelopes bearing the name and contact details of Pak Photocopy Graphics and Stationary Centre — a one-stop shop for students, professionals, entrepreneurs, soon-to-be-weds, excited new parents, artists, architects and the proprietor of Dandy School for Stitched and Stitching.

The tiny space, the size of my bedroom, is crammed to the gills with machines which make multiple copies at the push of a button, and more machines which can print anything worth printing on mugs, t-shirts, banners, folders, and something called “skins”. The shelves on all four walls are stuffed with every possible kind of adhesive, from glue to tape to sticky tack. There are boxes full of paper clips, thumb tacks, office pins. There are reams of paper, stacks of plastic sleeves in fluorescent colours, binders, folders, book bags, erasers, ink, staplers, staple-removers, hole punchers, rulers, pencil holders, pens and pencils, and of course the absolutely essential mouse pad.

Outside this space, in the narrow corridor shared by the photocopy machine and on-sale office furniture is a stack of backpacks for young children: Barbie in lurid pink for little girls, and Spiderman, Superman and Batman for the boys. For someone with an affinity with the animal kingdom is a backpack emblazoned with a couple of cartoon crows known fondly as Angry Birds. This one I buy for the young son of my employees, a tiny boy with huge eyes and a crucifix around his scrawny neck. He is four this year, and he shall start school soon, carrying his books and pencils and lunch in the spanking new backpack.

That is the vision I dream of as I wait inside the inner chamber of this House of Wonders. I am overseeing the printing of the first two parts of the Cultural Heritage Management Plan for the rock carvings endangered by the building of the proposed DiamerBasha Dam. The young men who undertake the job, Usman and Nomi, have cooperated with me as if it was their life’s work which was being churned out in multiple copies before being ring-bound by their co-worker, Tinku, in the space across the corridor, beneath the stairs leading out of this sunless vault. For several days I have enjoyed the humour, their camaraderie, the variety of clients coming with a variety of jobs to be done.

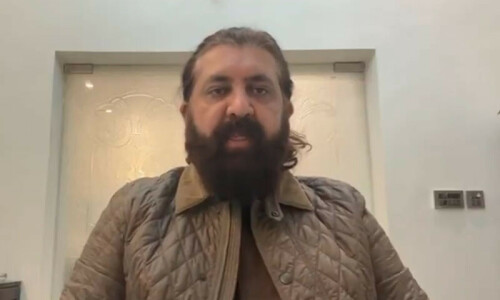

When one client requested Nomi to compose and print a birth and death certificate of the same hapless soul, Nomi remarked in Punjabi “You seemed to have killed off this chap as soon as he was born”. Nomi is a young bearded man with large, clear, kind eyes the colour of unripe grain. A man with a sense of responsibility as well as a sense of humour, Nomi is one of millions of young men in Pakistan today striving to make a living, capable of doing complicated things with the ease of a maestro.

I have met many such young men, living in small, congested alleyways, finding their way to work on a newly-leased motorbike or on the newly operated Metro bus. Educated, usually, at the local neighbourhood school, there are not many choices for these young men as far as maximising their potential is concerned. Constrained by resources and the need to support families, they go out in search of work usually after gaining a diploma from some computer academy offering them marketable skills. Nomi was a lucky one, gainfully employed, unlike the many who wander the pot-holed streets of our country, drifting aimlessly towards an uncertain future.

I watched Nomi and Usman as they patiently typed out letters of regret, applications for leave, invitations to dinner. Across the corridor Tinku printed out cards announcing the grand opening of a coffee shop where “politics are made more palatable — we serve a storm in every cup”. On the walls were samples of certificates awarded by Forward High School and Well Cut Hair Salon. Every so often, Billu Badshah would come with his mop and wipe the floor clean, leaving it shiny and immaculate. It was as if there was an unwritten code in this print shop: a job worth doing is worth doing well. I look up at Nomi’s green eyes; they are focused on the images of the rock carvings I am trying to conserve. His gaze lingers for a moment; he asks me if an Achaeminid warrior carved centuries ago is a relative of mine. I smile and nod my head silently. For Nomi the past is another country, and the future lies before him like an empty page waiting to be printed in full colour.