LONDON: Hardliners in Tehran and hawks in Tel Aviv and Washington, to say nothing of nervous Saudis and their Gulf allies, are already sounding alarmed at the prospect of a nuclear deal between Iran, the US and the international community.

Initial reactions from conservative opponents of President Hassan Rouhani have been predictably critical, with demands that all sanctions had to be lifted and Iran’s right to uranium enrichment recognised before any confidence-building measures could proceed.

So were the openly angry words from the Israeli prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, still hinting at a unilateral strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities. The agreement on the table in Switzerland was, he warned, “the deal of the century” for the Islamic Republic. But Israel — with its own undeclared atomic arsenal — would not be bound by it.

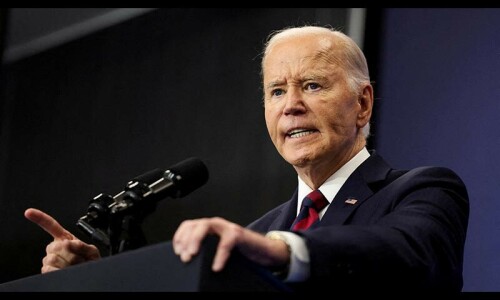

In the US, suspicions are likely to harden on Capitol Hill as the crucial details of the Geneva agreement, and especially relief from sanctions, become clear. The White House has already had to urge Congress not to tie its hands in the talks with Iran — or to sabotage them.

Saudi Arabia, which has dramatically demonstrated its chagrin at Barack Obama’s policies towards both Iran and Syria, kept silent on Thursday. But no one has forgotten — thanks to WikiLeaks — King Abdullah’s call to “cut off the head of the snake” in Tehran. Reports this week that the kingdom may acquire its own nuclear weapons from Pakistan were a reminder — perhaps intended as such — of the high stakes being played for in the Middle East.

The United Arab Emirates is also likely to be deeply unhappy about the beginning of a rapprochement between its powerful regional rival and traditional protector.

The US secretary of state, John Kerry, who was putting the finishing touches to the P5+1 agreement, has already had to reassure the Gulf states, as well as Jordan and Egypt, that America will not allow them to be targeted by Iran. Bahrain, with its restive and repressed Shia majority, worries about this.

Opposition everywhere should, however, be tempered by the fact that the emerging deal looks likely to be phased, limited and reversible, offering partial relief from crippling sanctions in return for verifiable progress on international monitoring of Iran’s nuclear programme.

In the Islamic Republic, the key to momentum will be sufficiently tangible economic improvements to build up the popular support Rouhani needs. The continuing confrontation over the war in Syria, where Tehran and Lebanon’s Hezbollah back Bashar al-Assad while the Saudis support the Sunni rebels, has been a vivid illustration of Iran’s regional reach and influence. For the moment though, Rouhani appears to enjoy the backing of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Israel’s opposition to Washington looks set to worsen relations that are already strained by differences over negotiations with the Palestinians. “Netanyahu’s outburst was a serious tactical error,” tweeted Nicholas Burns, a former senior US diplomat.

The Israeli prime minister has taken a very hard line on this issue for years, so it is no surprise he is so unhappy now. It is still hard to imagine, however, that Israel would attack Iran while an internationally backed agreement is in place.

By arrangement with the Guardian

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.