Historically, the area covered by Pakistan has been home to at least one highly urban civilisation nearly 4,000 to 5,000 years ago. Furthermore, subsequent dynasties ruling over the subcontinent developed a continuous culture of learning comparable to the rest of the world. Despite that, both Pakistan and India face problems of low literacy and millions of children out of school. Yet, some public facilities are available to the general population if the focus on learning and literacy is taken up as a relentless campaign to educate one and all within the country.

For instance, the shady, quiet street adjacent to the landmark Tollington Market of Lahore (recently renovated back to its original Exhibition Hall status) houses the Punjab Public Library set up by the British after their takeover of the Punjab in 1849. As you enter the premises of the library, on the right is a building that contains records of all the newspapers published since 1941. Bound copies of an exhaustive range of prominent (Dawn and Nawa-i-Waqt) and lesser known newspapers since are available to the public at large to browse through or use this archival data for research.

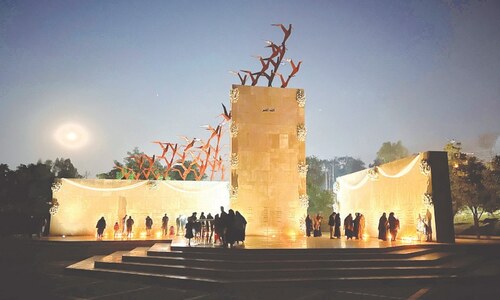

However, when you take in the view from Punjab Public Library’s main gate, you see an impressive structure. This is the baradari built by a Mughal nobleman, Wazir Khan, better known for the beautiful Wazir Khan mosque that he built in Lahore’s walled city. On all four sides of this baradari are placed four fountains whose symmetry and geometry leaves one to wonder at the exceptional sensibility of the Mughal builders.

The spacious, open and airy baradari now hosts some wooden stands on which a wide range of daily newspapers are placed and its central quadrangle has tables and chairs for people to sit and peruse them. On a bright, crisp Sunday morning you see students absorbed in reading the news of the day.

To the left of the baradari is the main library that has a vast variety of books placed on shelves in a number of halls. One of these halls is devoted to children’s books whose walls are decorated with bright, colourful posters exhorting young minds to develop a reading habit. On the first floor is a gallery that displays a number of unique Qurans in different scripts including some well-worn personal copies belonging to a number of famous subcontinental personalities.

The Civil Secretariat with its commanding colonial buildings and spacious, manicured lawns is two kilometres or so, just up the road from the Punjab Public Library. Hidden behind the main building is the mausoleum of Anarkali whom, the Emperor Akbar as the story goes, had had entombed alive. The myth surrounding this mausoleum has fascinated many over the years and more so when it was encapsulated in Imtiaz Ali Taj’s legendary play.

Anarkali’s mausoleum was actually built between 1605 and 1611 by the Mughal Emperor, Jehangir, over the grave of his wife, Sahib Jamal, who lived here in a grand villa surrounded by a pomegranate orchard. Although the tomb was placed in the middle of the mausoleum it was removed to one side of the hexagon building by the British who then used it as a church. Today, the mausoleum is the proud repository of archival material dating back to the Mughal era, Ranjit Singh’s rule of the Punjab and British colonial rule. It is all the more important since the British had made Delhi and its surrounding areas a part of the province of Punjab.

Thus, a treasure trove of rare, original manuscripts preserved here includes among others, all records connected to the 1857 War of Independence because Lahore was the headquarters. Others worth mentioning are the original sale deed by which the British sold Kashmir to Gulab Singh in 1854 for Rs7.5 million; Mirza Ghalib’s petition for his pension from the British and the record of the trial of Bhagat Singh.

Recently, Majeed Sheikh’s article in Dawn had carried a horrific description of archival material being trundled in wheelbarrows to be housed in a moldy stable in the vicinity of Anarkali’s tomb. Needless to say that such valuable archival material stored in our public buildings must be preserved at all cost as it is invaluable data for research in all kinds of disciplines. For that to happen, today’s technology should be used to digitalise and preserve all archival material and fields such as preservation of library archives, conservation of artefacts and historical research into archival sources must become an essential part of higher education in the country.

Lessons learnt from our rich literary heritage is that gains in literacy are a valuable asset for any nation and Pakistan’s ever burgeoning young population needs positive outlets to use their abilities for a brighter future. To ensure that, a culture of public libraries set up by public money or donated by private enterprise has to be initiated across Pakistan to provide a meaningful outlet to the youth in the country.

These libraries must be publicised well and equipped with computers and internet access for under-privileged students to use at their time and convenience. Nothing can be more practical, rewarding and fulfilling than having free access to books and computer technology for those who wish to educate themselves despite the setbacks of increasing inflation and poverty levels faced today.

The writer is an educational consultant based in Lahore.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.