IT road to cooperation with India

WHAT a difference can a year make. The climate for Indo-Pakistan cooperation seems to have changed radically since Mr Vajpayee’s visit in January last year for the Saarc summit.

Formerly tabooed subjects, such as Kashmir, canal waters, oil pipelines and the MFN status are on the table. There is talk of porous borders. Connecting people is the buzzword. But aren’t we forgetting the obvious, the enormous possibilities of cooperation in the field of information technology?

Arguably, IT is potentially the most promising area for cooperation between India and Pakistan. India’s enormous achievements in this field have gained world recognition, yet its expansion possibilities are not infinite. However, for rather mysterious reasons neither government is paying much attention to it. Pakistan, perhaps, because of its diffidence and apprehension and India because of pride in its pre-eminence in the field. Both need to shed their complexes and work for mutual benefit through the recognition of each other’s potential strengths and limitations.

Lest it be considered that IT’s case for mutual cooperation between the two countries is a bit of a stretch and that IT doesn’t matter, at least politically, let us recall two recent episodes which have highlighted the political potential of India’s IT prowess. Some five years ago, President Clinton pointed out, in a major foreign policy speech, that there are 700 high-tech companies in Silicon Valley headed by Indians, and called for an end to the “cold war estrangement” between the US and India, and the start of a systematic, committed relationship.

The Bush administration has not only followed that path but strengthened it further, notwithstanding its need for Pakistan’s friendship. More recently, Thomas Friedman reported in his column in the New York Times that the near-nuclear confrontation between India and Pakistan in mid-2002, was averted, at least partially, by the intervention of India’s IT leaders in Bangalore who warned the Indian government that it could have a disastrous effect on their industry.

The IT sector in India has grown from humble beginnings towards the end of the last decade of the 20th century to become an important part of its economy. The Indian IT software and services industry is expected to account for about 2.64 per cent of India’s GDP and 21.3 per cent of exports during 2003-04 and is projected to grow to seven per cent of India’s GDP and 35 per cent of exports by 2008. In little over a decade, the Indian IT industry has grown from producing an output of $150 million (mostly for export) to become a nearly $10 billion a year industry (with a quarter of the output being absorbed domestically). Pakistan is eager to emulate the Indian example. The question is: can it succeed? Pakistan’s efforts in the field of IT, as in many other fields of economic development, have been sporadic and characterized by missed opportunities and a failure to institutionalize individual success stories. The government’s efforts have generally been too little and come too late. As a result, Pakistan’s IT sector never achieved the critical mass of human talent pool, state support and a conducive environment for research and experimentation that is needed to make the industry a leading sector of the economy.

At the same time, with the worldwide boom in the IT industry, there was no dearth of opportunities abroad for promising young IT specialists stifled by the stagnant culture of “sifarish” and sycophancy at home. Although there were a number of multinational firms present in Pakistan, some even before the Indian IT boom took hold, the work base was narrow and their operations remained limited. Pakistan’s political, economic and cultural climate did not make it a preferred destination for outsourcing and related activities.

The Pakistani IT industry is hamstrung by the bureaucracy. There are squabbles as to who would run the IT ministry of the software export promotion Board, rather than encouraging IT professionals to take a lead. The military runs a major software outfit, National Database & Registration Authority (Nadra), which pre-empts the space for creative development of professional expertise. The IT professionals do not seem to have much clout or role in policymaking.

The Indian IT story is quite the reverse. It is one of painstaking nurturing by both the government and the private sector. Initially, up until the mid-1990s, Indian companies were hired mostly to do tedious work — writing repetitious code for software programmes and so on. These jobs were ignored by most information technology professionals in the US and other countries, since salaries were low and the offices were mostly white-collar sweatshops located in Chennai and Bangalore. India’s reservoir of educated and skilled personnel was able to meet the ever-increasing demand for these “dirty” IT jobs.

The better trained among them were also recruited by US companies to work on H-2 visas in United States. Many of them cut their teeth on the Y2K and dotcom booms. By networking with highly trained IT specialists many of whom had established their own firms in the Silicon Valley, the Indian IT community abroad fuelled the growth of the Indian IT industry.

This led to the rapid expansion of giant firms like Infosys, Wipro, Tata Consulting Services (TCS) and a host of other companies on the back of the outsourcing boom, which followed the bursting of the technology bubble in 2002 and resulted in the export of technology-oriented jobs from the US. The wages in the IT industry in India reportedly rose an average of 12 per cent in 2004 and were projected to increase by another 15 per cent in 2005, blunting its competitive edge.

The breakthrough in telecommunications technology was an essential element in making Bangalore a major IT centre. In 1987, Texas Instruments opened a software-development centre in Bangalore, followed by Hewlett-Packard in 1989. Texas Instruments established a satellite link between Bangalore and its Dallas headquarters and shared that link with other companies.

That opened an electronic highway for Indian companies on which software jobs travelled from the US and finished products were sent back from India. Almost all major technology companies established their presence in India. They did so not just to be able to produce for the US market. In many cases, they moved there to profit from the domestic Indian market, which is expanding rapidly.

What keeps India’s IT industry ticking and competition at bay, despite its phenomenal growth, is that it has both a large reservoir of trainable workforce, willing to work at a fraction of the costs in the US and other industrialized countries, as a well as an enormous infrastructure of education and human development built during the last half century.

It is estimated that India has over four million technical workers, over 1,832 educational institutions and polytechnics, which train more than 67,785 computer software professionals every year. India’s sheer size and its continuing investment in the expansion of its educational system enables it to rapidly expand the number of computer science and knowledge workers, as it is now doing with an investment fund of $1 billion.

The elite Indian Institute of Technology, which produces 4,000 graduates (only two per cent of the 200,000 students who apply are admitted) each year from the seven schools that provide the backbone of India’s IT infrastructure. Although they are formally a part of the public education system, they receive liberal donations from the alumni and the private sector. As a result. when the tech industry boomed in the mid-1990s, the government increased enrolment at the IITs — 50 per cent in the past seven years — in order to produce more tech workers.

Pakistan’s ability to partake in the current outsourcing boom is limited by the inadequacy and the narrow base of its educational system. Its past neglect of the social sector in general and education sector in particular, as well as the low social and economic esteem enjoyed by its academics, stands in the way of producing on a large scale the kind of labour force required.

While Pakistan needs to repair and overhaul its leaky and outdated educational and human resource development system, it should also look at the possibility of benefiting through mutually cooperative arrangements with countries which have achieved outstanding results in these areas.

Pakistan’s IT industry can benefit a great deal by seeking collaborative arrangements with Indian IT companies which have begun to feel the market pressure in hiring quality personnel. The rate of turnover in the Indian IT industry is very high and wages have reportedly risen by an average of 12 per cent in 2004 and were projected to increase by another 15 per cent in 2005, blunting its competitive edge. These developments provide a conducive environment for collaboration between the IT firms of the two countries which could prove to be of mutual advantage to both countries.

A major hurdle in the way of such cooperation is the slow speed of electronic communications between the two countries. Typically, Internet connectivity between our countries is via the US, which adds delay and cost. At a time when both countries, are heavily investing in optic fibre cables, it would not cost much to take such a connection to the border as well. This would help increase market size for the products of both countries. Since India has access to its own and other countries’ satellites, we could get greater access by having a leasing or transit arrangement.

As we are witnessing a growing spirit of cooperation on the oil pipeline and other issues, including Kashmir, there is every possibility that India will be willing to engage in similar cooperation in the IT area, to the mutual advantage of both countries. Cooperation in IT will inevitably have to be linked to cooperation in the field of higher education and will lead to the invigoration of academia and research institutes, through healthy interaction and exchange.

E-mail: sm_naseem@hotmail.com

A blow to European Union

THE negative vote, by large majorities, in two founding member states of the European Union, in referendums on the new constitution has caused shock as well as concern to proponents of regional cooperation. France, together with Germany, was regarded as the driving force behind the European movement. Rejection of the new constitution by a plurality of 55 per cent there is no doubt a reflection of the current unpopularity of the Chirac government, but also a demonstration of dissatisfaction with the direction envisaged in the constitution.

The Dutch vote, three days later, by an even higher plurality, shows how far the elite in the government had lost touch with the public at large. While the Netherlands had been in the forefront of European economic integration since 1957, its electorate has voiced strong reservations over the goal of political integration that has been stressed in the proposed constitution. There are other undercurrents of national concerns that have emerged, which point to lack of support for turning the European Union virtually into the United States of Europe, a la USA.

The establishment of the European Economic Community in 1957, with six founding members, has been regarded as a landmark venture in multilateral cooperation that started a trend in the post-war world. Regional cooperation in Europe became a model for regional integration and set the pace for the rest of the world by a progressive increase in areas of integration. The community became the European Union in 1992, when its membership had reached 13. It so accelerated economic and social progress in the member countries and virtually the whole of Europe joined it. By 2004, the membership reached 25.

As the membership was due to reach 25, the organization began work on a constitution that would provide the foundation for a truly united Europe. It required a great deal of negotiations and debate to reach consensus among the authors representing membership at different stages of economic development. The founders, notably France and Germany, envisaged a change in the principles of equality and consensus that had hitherto characterized the decision-making in the grouping, to a more pragmatic system in which the role of members would reflect their size and strength.

Before the constitution could take effect, it had to be ratified by all 25 members, in accordance with their procedures. In many member states, ratification by parliament was sufficient. However, many states either chose to go to the people through a referendum, on account of the important changes involved, or were obliged to do so by their laws.

The agenda for European integration had been driven from its early days by the elites in various countries, and major decisions were taken without a reference to the electorates in member states. It was only when such far-reaching changes as the conversion of the grouping from a community to a union, through the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992 were being undertaken that the process of national ratification was invoked. This was secured narrowly in many cases, such as in France, where the supporters had a plurality of only one per cent over the opponents.

The process of ratifying the draft constitution of the expanded union has brought to surface many popular discontents with the scope and direction of European cooperation. So far, 10 countries have ratified the constitution. These include Germany, Italy and Spain. However, the rejection by two founding members is a setback. President Chirac has urged the other members to continue with the process of ratification. If the other 23 members ratify, France and the Netherlands might be persuaded to reconsider.

However, the fact remains that the two ‘noes’ have drawn attention to the need to move forward with greater deliberation, and not impose the goals of a few visionaries on a continent consisting of numerous states with their own history and traditions. The next meeting of the EU council of ministers, due in Brussels on June 16-17, will take up a host of complex issues thrown up by this rejection.

The French rejection was primarily a vote of no-confidence in President Chirac, during whose incumbency unemployment reached 10 per cent, despite the fact that the French economy was doing well. The main problem was that new industries were being set up by French corporations in countries with cheap labour, such as Romania and Madagascar. Another factor in the rising unemployment was immigration, mostly from North Africa, and the fact that the immigrants were Muslims, with a different culture, led to the upwelling of racial and religious prejudice. The feeling also grew that with the EU expanding to 25 members, the prominence France had enjoyed would be diluted, and, indeed, its national interests sacrificed for collective advantages.

In the case of the Netherlands, which was already witnessing popular discontent over their small country making the highest per capita contribution to the budget of EU (5,000 euros), but getting back only 2,000 euros, immigration became a major issue, with 1.7 million immigrants in a population of 14 million. The Dutch had seen their living costs go up due to the overvalued euro, and became convinced that the aim of creating a European super-state would mark the end of their proud history.

Many Dutch voters, including leaders of political parties, stated that while they had gone along with economic integration, they were not ready for political integration. Many opposed the creation of posts of president and foreign minister that the constitution proposed.

The major advocates of European integration, Chancellor Schroeder of Germany and President Chirac of France, are going through a slump in their political fortunes, and would have no choice but to accept this setback for the time being. Many other major players have a stake, with Britain, which assumes the presidency of EU in July, well placed to assume a leading role. The US, despite the reservations of President Bush over European dissent with its war on Iraq, has publicly affirmed its faith in the alliance with a “united Europe.”

Viewing this event in a global context, doubts will be accentuated about the process and scope of globalization, with which the developing countries are already discontented. The most serious outcome of the Franco-Dutch rejection of the constitution would be the need to pay attention to all members, great or small. The general expectation is that the EU will continue to pursue its economic policies but the process of consultation will be stepped up and that of hurrying political integration slowed down.

It is generally felt that the rejection of the constitution by France and the Netherlands will have a negative effect on the prospects for the admission of Turkey. The immigration issue has been a major factor in the negative vote. The vote affects not only the employment but also raises concerns over the fact that most of the immigrants are Muslims, who are considered alien to European traditions and culture.

With the rate of population growth falling, Europe will experience growing labour shortages, for which immigration would be the only answer. However, many European countries would prefer to import workers from Eastern Europe, rather than the belt of Muslim countries to the south. In the post 9/11 scenario, historical prejudices and centuries-old antagonisms are being revived and that may even affect the process of globalization. Signs are visible in the reaction to the quantum increase in Chinese textile exports that have taken place under the WTO regime. Thus, the emerging sentiment in Europe suggests that the pace of global economic reform will be affected as protectionism and restrictions on movement of labour become stronger.

Justice before politics

By Floyd Abrams, Bob Barr and Thomas Pickering

AFTER the attacks of September 11, 2001, came widespread shock and horror — and some tough questions. Could the United States have prevented this catastrophe? What corrective action might we take to protect ourselves from other terrorist attacks?

After political struggles and initial resistance by many political leaders, Congress and the president created the September 11 commission in 2002. This bipartisan group of 10 prominent Americans was charged with conducting an independent and complete investigation of the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and with providing recommendations for preventing such disasters. In July 2004 the commission released its report, and in December Congress passed legislation to implement many of its recommendations.

In the spring of 2004, the scandal involving the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib became public. Additional allegations of abuse surfaced in connection with prisoners detained by the United States at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and elsewhere. Many Americans asked themselves the same painful questions about these allegations: How could such terrible actions have taken place? Who was responsible? What reforms might we implement to prevent such problems? Once again, a year later, these questions remain unanswered.

We believe that the American public deserves answers. We are members of the bipartisan Liberty and Security Initiative of the Constitution Project, which is based at Georgetown University’s Public Policy Institute.

We have joined with other members of the initiative — Republicans and Democrats, liberals and conservatives — to call for the establishment of an independent bipartisan commission to investigate the issue of abuse of terrorist suspects. We urge Congress and the president to immediately create such a commission and to use the 9/11 commission as a model.

No investigation completed to date has included recommendations on how mistreatment at detention facilities might be avoided. Even the Pentagon’s much-heralded report by Vice-Adm. Albert T. Church, completed in March, concluded only that there were “missed opportunities in the policy development process” and that these opportunities “should be considered in the development of future interrogation policies.”

Establishing an independent, bipartisan commission would also be beneficial for US relationships abroad. The abuse of terrorist suspects in US custody has undermined the United States’ position in the world. This is a time when we should be making extra efforts to reach out to Muslims and to ask them to work with us in the war against terrorism. Instead, our failure to undertake a thorough and credible investigation has created severe resentment of the United States.

An independent, bipartisan investigation can generate widespread acceptance and support for its findings. Only with such a commission are we likely to enact the reforms needed to restore our credibility among the nations of the world.

We must move beyond the partisan battles of our highly charged political climate. To provide a credible investigation and a plan for corrective action, and to show the world that the United States takes seriously its obligations to uphold the rule of law, we urge Congress and the president to establish a commission to investigate abuse of terrorist suspects. — Dawn/ Washington Post Service

Floyd Abrams is a lawyer who specializes in First Amendment cases. Bob Barr, a former Republican representative from Georgia, deals with civil liberties issues for the American Conservative Union. Thomas R. Pickering, a former diplomat, has served as undersecretary of state and ambassador to the United Nations.

Advani’s finest hour

THIS was his finest hour. BJP chief Lal Krishna Advani wanted to turn a new leaf in the history of relations between Hindus and Muslims in the subcontinent, different from the past frozen in animosities and bitterness.

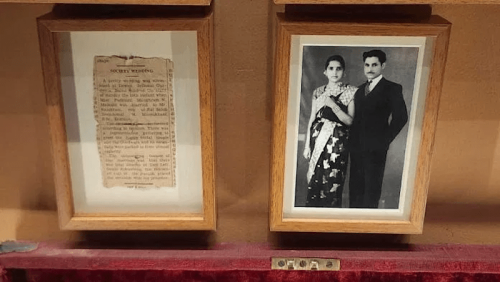

He hailed Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah as “secular.” Advani even “regretted” the demolition of the Babri masjid which he watched going down brick by brick.

Advani, a hardliner, probably thought that he and his party could alone initiate a new process of understanding between the two communities, nay between the two countries, to usher in an era of peace. He courageously enunciated his views, knowing well that in the process he might destroy himself. Yet, this was the way he felt, not emotionally but thoughtfully. But he should have known the RSS — he is its product. It has only anti-Muslim as its ideology. It cannot change because it has lived since 1925, the year it was born, within the walls of bias and prejudice that it has built.

When Advani said, “Jinnah was a great man who had espoused the cause of secular Pakistan,” the BJP chief tried to remind the Islamic state that its founder wanted secularism to be its ethos. For Advani, who had plugged a communal line all his life, it was a big departure. In a way, he raised the perennial question: Why religion and politics were mixed in Pakistan or, for that matter, in India?

I expected a discussion on those lines. But the RSS parivar, dyed deep in saffron, does not want such a debate which would challenge its raison d’tre. Instead, it has made Advani resign from the BJP presidentship after futile efforts to make him withdraw what he had said in Pakistan. Two points have been proved once again. One, the BJP continues to be under strict discipline of the RSS. Two, it does not want to dilute its ideology of Hindutva.

Advani is not a novice in politics. Nor is he given to histrionics. His praise for Jinnah in Pakistan was not an off-the-cuff remark. What he said was measured and discussed before he left New Delhi. The furore in the Sangh parivar was more than he expected. That explains why he wrote his resignation letter in Karachi itself. But there was no doubting his genuineness in saying what he did.

Probably, Advani, who built up the BJP after the erstwhile Jan Sangh members parted company with the Janata in 1980, felt that his party could not make a headway with the anti-Pakistan posture which took the shape of anti-Muslim sentiment. (Muslims in India constitute 15 per cent of the electorate and they, probably to the last person, shun the BJP.) A party that wants to rule India one day could not afford to run down the founder of the second largest Muslim country in the world. Yet, the BJP’s anti-Jinnah posture is the grist to its propaganda mill.

Historically also, the BJP is wrong. Jinnah advocated the two-nation theory till he secured an independent country comprising the states where the Muslims were in a majority. He accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan which gave autonomy to the Muslim majority areas but kept India together though with a weak centre. In his personal report No. 41, Mountbatten recorded on April 24, 1947: “I am still doing everything in my power to get the Cabinet Mission Plan accepted. But Jinnah and the Muslim League leaders are convinced that Congress has no intention whatever of complying with the spirit of the Plan.”

Jawaharlal Nehru sabotaged the plan when he said that Assam could opt out of the group to which it was allotted in the three-group federal structure which the Cabinet Mission Plan had proposed. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad wrote in his book, India Wins Freedom, “I warned Jawaharlal that history would never forgive us if we agreed to partition (instead of the Cabinet Mission Plan). The verdict would then be that India was divided as much by the Muslim League as by the Congress.”

That Jinnah wanted Pakistan to be secular was also clear from the name he gave to the country. He called it Pakistan. The word, ‘Islamic,’ was added after his death. After the acceptance of Pakistan Jinnah said: “You are free to go to your temples. You are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed; that has nothing to do with the business of the state. You will find that in course of time, Hindus will cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the state.”

I know from experience that our family felt secure in Sialkot city once the statement was made. We decided to stay back. But when the Muslims ousted from India began to pour in to the city, our living became impossible. During partition, the two communities rendered 20 million homeless and murdered one million in cold blood.

At a time when India and Pakistan are in the midst of the biggest exercise to normalize relations, questioning the credentials of Jinnah, as the RSS parivar is doing, is like renewing the age-old debate whether Pakistan should have been there. This is one way of sabotaging the peace efforts. I think the matter was settled once and for all, if there was any doubt, when Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee travelled by a bus to Lahore and wrote in the visitors’ book at the Minar-e-Pakistan that the integrity and prosperity of India depended on the integrity and prosperity of Pakistan. (The minaret is located at the place where the Pakistan Resolution was passed in 1940).

Advani is lonely today. Even the best of his supporters, the younger lot whom he groomed, are quiet. This should awaken Advani to the realities of today’s politics in the country. Power is with the chair. Once you lose it, even the best of friends shun you. However, his acceptance in the country has increased. He should be satisfied that he has won hearts in Pakistan where he was once demonized. In the process, he has made even the hardliners in that country think that if Advani can change, the entire edifice built on differences between India and Pakistan, between Hindus and Muslims, can be pulled down so that the two communities live in harmony. After all, they have lived together for centuries.

It would be a pity if hardliners in India were allowed to have their way at a time when the desire for peace with Pakistan is strengthening. All that the BJP leaders have to realize is that India’s ethos is secularism, not Hindutva. In the same way, the Muslim leaders in Pakistan have to recall that Jinnah did not want religion to be mixed with politics.

The writer is a leading columnist based in New Delhi.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.