Cricket is perhaps the only sport in which a captain actually does more than just play the game or wear an armband.

Apart from having good, consistent cricketing abilities, he has to also exhibit a penchant for the kind of leadership found in a military general or in a political leader.

Most good cricket captains have also been inspirational and innovative thinkers. In fact, sometimes this quality has taken precedence over cricketing ability, as was demonstrated by one of the finest captains the game has seen in the shape of Mike Brearley, who captained the England side between 1977 and 1979 and then again in 1981.

Brearley, who was at best a mediocre opening batsman, lifted the English side to become the world's leading Test team between 1977 and 1979.

But this supremacy crumbled after his retirement, so much so that two years later, he was recalled to lead the team again (at the age of 43) half-way through the 1981 Ashes series against the Aussies.

England were 1-0 down in the series when Brearley was recalled. His presence turned the tables and England went on to win the series 3-1!

A cricket captain has to manoeuvre his men like pieces on a chessboard. This allows the whole idea of 'mind games' to play an important part in the game.

One of the finest practitioners in this regard was Australian skipper, Ian Chappell. When Chappell was made the Australian captain in 1971, he consciously went about changing the way a team was supposed to conduct itself on the field.

He asked his players to grow their hair long and get rid of the idea of wearing their cricketing whites as if they were about to attend a formal wedding reception.

Under Chappell, the Australian side became one of the most feared and intimidating teams in cricket. Its quick bowlers chugged beer in the dressing room and publicly declared that they liked watching batsmen bleed.

It was under him that the Australian side developed the kind of never-say-die attitude it is still famous for.

Sometimes cricket captains have had to quite literally play the role of statesmen. That's exactly what another great captain, Clive Lloyd, found himself doing when he was handed the captaincy of an underachieving West Indian side.

Though he managed to lead the Windies into winning the first cricket World Cup in 1975, the same year the team was hammered in a Test series 5-1 by Ian Chappell's Australians.

Lloyd managed to gel them well and play as a fighting unit. Inspired by the radical black civil rights movement in the United States, Lloyd convinced the players that through cricket, the Caribbean nations could rise above their political problems and differences and make the West see that they were a lot more than just a bunch of happy-go-lucky 'black entertainers.'

For the next 15 years, the Windies would go on to dominate the cricketing world as perhaps the best cricket team of the 20th century.

So, now keeping in mind all that makes a good cricket captain, who have been Pakistan's finest in this respect?

One should remember that apart from being a skilful player and a good, innovative thinker, a Pakistani cricket captain also has to be a clever politician, considering the politicised and volatile state of the game in this part of the world.

Ever since Pakistan made its debut as an international Test playing nation in 1952, it has had 30 Test captains!

Out of these only eight's captaincies have survived for five years or more, and that too in stints.

Experts and cricket historians all agree that captaining the Pakistan side is perhaps one of the most stressful tasks. A Pakistani cricket captain has to not only tackle the power games that are played in the country's cricketing board, but he also has to face constant player rebellions, groupings and power tussles that Pakistan cricket teams are infamous for.

And then, of course, there is the knee-jerk media and an entirely emotional fan base that blows hot and cold at the drop of a hat.

Yet, not only has Pakistan continued to generate an impressive number of exciting and skilful cricketers, it has also produced its own batch of Brearleys, Chappells and Lloyds.

Below is a study of some of the best cricket captains of Pakistan. A position that usually rotates between men like the heads of state do in banana republics.

Abdul Hafeez Kardar

Given the task to lead an almost entirely inexperienced bunch of talented young cricketers of a country whose first cricket board could not even fully pay for the players' cricket kit and equipment, Kardar soon turned the team into a side that every Test playing nation of the world came to admire.

In Kardar's six-year-reign as skipper (1952-58), Pakistan managed to win a Test against every Test side of the world, except, of course, South Africa, that at the time was under an apartheid regime and was boycotted by India, Pakistan and the West Indies.

Under Kardar, Pakistan played 23 Tests; it won 6 and lost 6 while drawing the rest - an impressive record for an underpaid team of young novices.

Despite his autocratic demeanour and average cricketing skills, Kardar was deeply respected by his teammates and was treated as a father figure by most of the team's young players.

He almost always drew the playing strategies and plans on his own and expected his players to stick to what he had laid out in team meetings. Dissenting views and voices were discouraged.

Another thing Kardar managed to do was to strike friendships with influential political leaders who subsequently stayed away from meddling in the affairs of the board and the team.

Since Kardar had led the young and cash-strapped team to victories against some of the top sides of the world, his almost dictatorial hold over the team and his overwhelming influence in selection matters were largely tolerated by the board.

But sometimes this did lead to him preferring friends over other more deserving candidates. For example, he kept the highly talented brother of the equally talented batsman, Hanif Mohammed, out of the squad just to make room for his buddy and drinking partner, Maqsood Ahmed.

Raees Mohamed was taken on tours but never given a chance because that would have meant dropping Maqsood, even though Maqsood too was a skilful batsman.

Kardar's departure suddenly created a long-lasting leadership vacuum in Pakistan cricket.

As the fans and the media couldn't stop comparing every new captain with Kardar, the team's performances nose-dived and it saw the coming and going of seven captains between 1958 and 1975.

Captaincy Record (1952-58):

Tests: 6 won, 6 lost, 11 drawn.

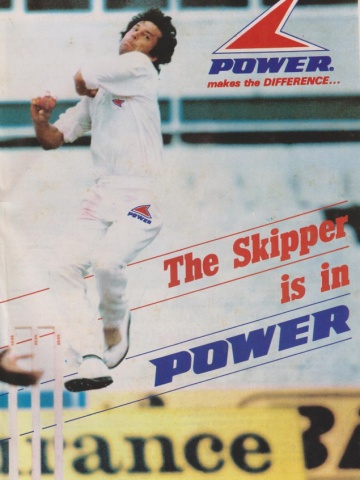

Mushtaq Mohammed

From the year that Kardar retired (1958) till Mushtaq was appointed as captain (in 1976), Pakistan had played 48 Tests (under seven captains) out of which it could win only 5 and lose 15.

Kardar was made the chief of the Pakistan Cricket Board in 1972 and it was he who appointed the captain who would finally be able to beat his (Kardar’s) long-standing record of 6 victories. That man was Mushtaq Mohammed.

Unlike Kardar, Mushtaq wasn't an Oxford graduate. In fact, he never attended any college. He was still in school and just 16 when he was selected to represent the Pakistan side in 1959.

Coming from Karachi's famous cricketing family, the Mohammed brothers, Mushtaq had established himself as a solid middle-order batsman and a useful leg-break bowler in the team. He was 33 when he was made the captain in 1976.

There was one thing common between Kardar and Mushtaq, though. The latter was equally stubborn. It was this aspect of Mushtaq's personality that almost cost him his captaincy during his very first Test series as captain.

No Pakistani captain before Mushtaq had ever demanded a pay raise for his players. But Mushtaq did exactly that during Pakistan's home series against New Zealand in 1976.

The Kardar-led cricket board out-rightly refused the demand and in fact threatened to remove him as captain. Mushtaq responded by leading the team to win the New Zealand series 2-0.

With a huge win in the bag and support of the team’s top players, Mushtaq again asked for a pay raise for the team just before Pakistan’s long tour of Australia and the West Indies. Both were the top two sides in the world at the time.

The board again refused and finally dropped Mushtaq as captain. But just before Intikhab Alam was set to return as captain, the government stepped in and agreed to meet Mushtaq’s demands.

Mushtaq was reinstated as captain and led Pakistan to a gruelling 5-month tour of Australia and the West Indies that included eight Tests.

After being 1-0 down against the mighty Australians, Mushtaq regrouped his troops and managed to famously win the third Test to square the series 1-1.

It was during the Australian series that Mushtaq (inspired by the aggressive on-field tactics of the Australian side), adopted sledging and intimidation.

The turn-around came during the first Test when as a tradition some Australian players came into the Pakistan dressing room to share a few beers.

Mushtaq asked Australian tearaway fast bowler, Dennis Lillee, how can he expect the Pakistani players to share a drink with the Australians when the latter had abused and cursed them on the field?

Lillee laughed and replied: ‘Drink up, Mushy, what takes place on the field, stays on the field.’

From the second Test onwards, Mushtaq encouraged his players to abuse the Australians on the field, and during the third Test he gave his quick bowlers, Imran Khan and Sarfraz Nawaz, a free hand to bowl as many bouncers as possible to the Australians.

Pakistan’s flamboyant opening batsman, Majid Khan, once related how, apart from what Mushtaq had learned from the Australians, he also had a great knack of correctly reading how a pitch would play.

Just before the third Test in Sydney, Mushtaq eyed and marked out a spot just short of good length on the pitch and asked Imran to keep hitting that mark.

Consequently, the Australians just could not understand how Khan and Sarfraz were getting so much pace and lift on a pitch on which Australian tearaway pacers were being taken to the cleaners by the likes of Asif Iqbal (who scored the only century of the match).

On the West Indies leg of the tour that included 5 Tests, the team showed exceptional fighting spirit against a belligerent West Indian side and hostile crowds, going down 2-1 in a hard-fought series.

Mushtaq lost the captaincy when he joined five other Pakistani players to play for Australian media tycoon, Kerry Packer’s renegade World Series Cricket (WSC), in Australia. The event destroyed a number of teams.

Mushtaq, thus, missed the two series against England in late 1977 and 1978. However, after Pakistan had lost the away series against England 2-0 (under Wasim Bari), the board lifted the ban on the five players.

Mushtaq was recalled as captain for India’s tour of Pakistan in late 1978. The series was won by Pakistan 2-0. In the third Test in Karachi, Pakistan was set a seemingly impossible target of chasing 164 runs in 25 overs on the fifth day.

Though one-up in the series, Mushtaq refused to close shop and decided that his team would attempt to win the Test. He promoted Asif Iqbal to open the batting with Majid Khan. He then sent in young Javed Mianad after Majid fell early.

In an era when ODI cricket was still new and the T20 format was decades away, Asif and Javed thrilled the huge crowd at Karachi’s National Stadium by scoring at almost 7-runs an over.

But Pakistan still needed 44 runs in four overs when Asif got out. Instead of sending in Zaheer Abbas, Mushtaq gambled again and sent in the young hard-hitting all-rounder Imran Khan.

Khan struck a quick-fire 31 and Pakistan reached the target with an over and a half to spare.

When Mushtaq led Pakistan to a 1-0 series victory against New Zealand (in New Zealand) in 1979, he surpassed Kardar’s record of 6 victories.

Pakistan then went on to level the series against Australia (1-1), before Mushtaq was replaced by Asif Iqbal as captain for Pakistan’s 1979 tour of India. He was 37 at the time.

Though Mushtaq lacked Kardar’s charisma and educational background, he was armed with a bagful of street-smart tricks he had gathered from playing on the roads and in the cricket clubs of Karachi. He also had a wealth of experience of playing county cricket in England.

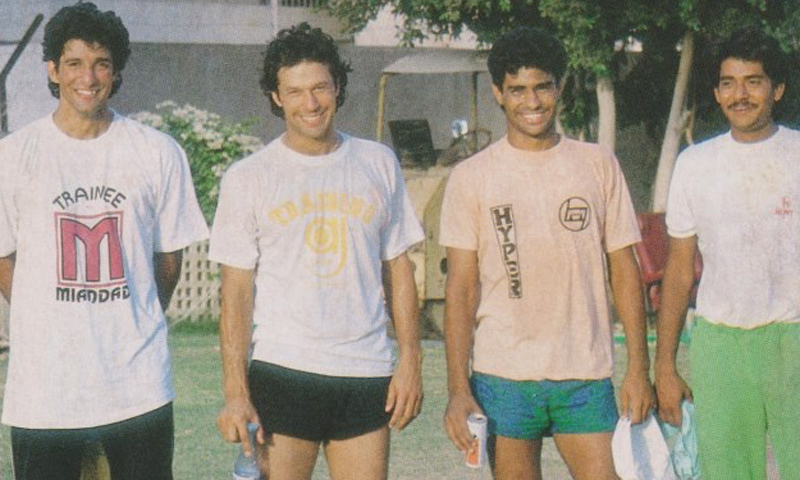

It was under Mushtaq’s captaincy that Imran transformed into becoming a formidable fast bowler. Though not a harsh disciplinarian like Kardar, Mushtaq was a firm and empathetic man-manager. He got the best out of two of Pakistan cricket’s most volatile and eccentric players, Wasim Raja and Sarfraz Nawaz. And it was also under Mushtaq’s guidance that Imran transformed into becoming a formidable fast bowler.

He was asked to return as captain in 1980 when Asif Iqbal retired after losing to India 2-0. Mushtaq declined and instead suggested 23-year-old Javed Miandad for the job.

Captaincy Record (1976-77/1978-79):

Tests: 8 won, 4 lost, 7 drawn.

ODIs: 2 won, 2 lost.

Javed Miandad

During a discussion on great Pakistani cricket captains with some former Test players at a gathering a few years ago, I noticed that though Javed Miandad’s name kept coming up, it wasn’t always about his captaincy skills.

There is still unanimous agreement across the board about Miandad being perhaps the greatest batsman ever produced by Pakistan. But there is, however, no such agreement on him as a captain.

When Mushtaq Mohammad suggested his name to the cricket board in 1980, Miandad was just 23-years-old.

But the board’s new chief, Nur Khan, agreed with Mushtaq that the young batsman had a sharp cricketing brain and his batting exploits had already earned him the respect of his seniors.

Miandad won his first series 1-0 (against the visiting Australians), but went down 1-0 against the West Indies and then 2-1 against Australia in Australia.

Miandad exhibited his youth and inexperience by accusing the senior players for the team’s defeat in Australia. This did not go down well with the team and in early 1982, ten players, led by Majid Khan, refused to play under him. They demanded his removal.

Miandad refused to step down and was supported by Nur Khan. He led a brand new team against the visiting Sri Lankan side and won the first Test match easily.

Mohsin Khan, Wasim Raja and Iqbal Qasim broke ranks from the rebels and joined the team for the second Test. But when Pakistan narrowly escaped defeat against the inexperienced Lankans in the second Test, Miandad offered his resignation to Nur Khan.

Nur Khan encouraged Miandad to continue and soon Imran Khan, Mudassar Nazar, Sarfraz Nawaz and Wasim Bari too broke away from the rebellion.

It is believed that Miandad had asked the local employers of the rebelling players (banks and PIA), to terminate their playing and employment contracts. The only players who still refused to play under Javed were Majid and Sikander Bakht.

Nevertheless, Miandad stepped down after the Lankan series (that Pakistan won 2-0) and agreed to play under any captain except Majid or Zaheer. Imran Khan was appointed as the new captain.

Miandad returned as captain in 1985 when he replaced Zaheer Abbas (who in turn had replaced Imran after he got injured). Javed lost a series against New Zealand before making way for Imran’s return in 1986. Miandad became the vice captain.

Captaincy rotated between Imran and Miandad across the late 1980s. And even when Miandad led Pakistan to a 2-1 series victory against England in 1992 (after Imran’s retirement), he faced yet another rebellion when the team performed miserably in an ODI tournament in Australia in 1993-94.

This time the rebellion was led by the celebrated fast-bowling pair of Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis.

This was Miandad’s last stint as captain.

So how can a captain who failed to retain his position for more than two years at a stretch and faced two players’ rebellions be considered great?

To begin with, out of the 34 Tests that he captained, he won 14 and lost just 6.

Miandad had one of the sharpest cricketing brains and understood the game like any good cricket captain would. But unlike a good captain, his man-management skills were a disaster.

He was a master at sledging and at ‘working up the opposition’ with his continuous chatter and insults. And though he used this as a tactic to disturb the opposition, it also got the team into unnecessary controversies.

But interestingly many experts believe that more than a captain, Miandad was the perfect vice-captain. Apart from captaining the side whenever Imran Khan was injured or unavailable, Miandad always willingly returned to being Imran’s deputy.

Former Australian skipper, Ian Chappell, and Pakistani cricket commentator, Chisti Mujahid, once described the Imran-Miandad combination as one of the most formidable think-tanks in the game.

This combination turned the Pakistan team into a strong side in the late 1980s, and both the players then played a leading role in helping Pakistan win the 1992 cricket World Cup.

During Pakistan’s 1987 tour of England, Pakistan, after being one-up in the series, was in danger of losing the fifth Test match when England needed 118 runs in about 20 overs.

Batting aggressively, England batsmen seemed to be well on their way when captain Imran and his deputy Miandad decided to halt the runs in a unique manner. Miandad martialed the field on the off side while Khan (who was also bowling most of the overs), looked after the field on the on-side.

Famous commentator, Richie Benuad, was fascinated by the tactic. Pakistan saved the game and won its first ever series against England.

Miandad was also instrumental in forcing Imran to drop an out-of-form Abdul Qadir and fly in left-arm spinner, Iqbal Qasim, for the last Test of the 1987 Pakistan tour of India.

Miandad convinced Imran that on a turning wicket, not only Qasim’s bowling will be effective, but since he was a left-handed batsman, he could neutralize India’s spin bowling attack. Pakistan won the game and the series.

Miandad retired from cricket in 1996.

Captaincy Record (1980-82/1985-86/1988/1992-3):

Tests: 14 won, 6 lost, 14 drawn.

ODIs: 26 won, 33 lost, 1 tied, 2 no result.

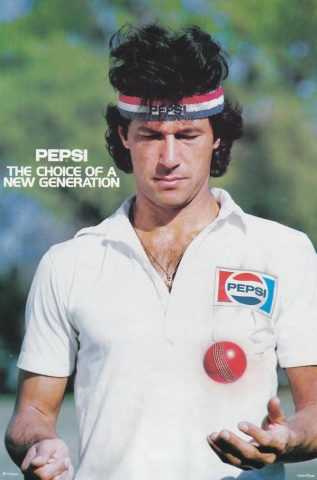

Imran Khan

The decision to make Imran Khan the captain of the Pakistan cricket team in 1982 took a lot of people by surprise.

Known more as a flamboyant fast-bowler/bowling all-rounder and ‘playboy,’ nobody quite expected him to ever lead the national cricket team. Not even Imran himself.

When Javed Miandad was ousted by a players’ rebellion, he was expected to be replaced by either Zaheer Abbas or Majid Khan.

But since Majid and Zaheer were the central figures in the rebellion against him, Miandad (after resigning from the captaincy), made it clear to the cricket board that he was not willing to play under either of the two aspirants.

The board came up with a compromise candidate in the shape of Imran Khan. Khan was reluctant. His close friends warned him that captaincy would destroy his career and form.

Nevertheless, after some thought, Khan accepted. Quite the opposite happened to his career and form. Not only did he win 7 of the first 12 Tests that he captained, his form as all-rounder also reached a peak.

With his performances he was able to quickly gain the respect of his teammates and successfully weave a fragmented side into a tightly-knit unit. However, in 1983 he suffered a career-threatening stress fracture in one of his shins that prevented him from bowling.

He tried to hang on as a batsman and captain, but couldn’t help arrest the team’s sudden decline. He finally decided to take a break from the game and heal his fracture.

When he returned to the team in 1985, Miandad was once again the captain but he voluntarily handed over the captaincy to Khan.

Khan’s second stint as skipper was equally successful but at the same time a lot more controversial.

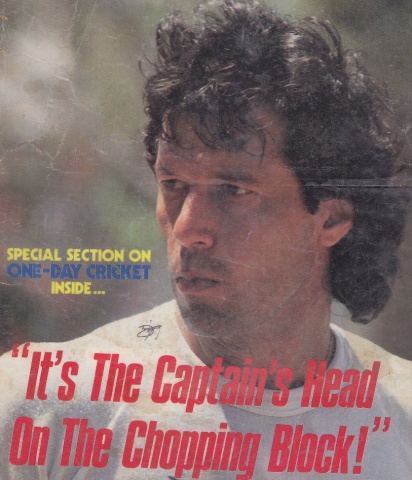

After reestablishing himself in the team as its premier all-rounder and captain, Khan began to exercise an almost dictatorial hold over the team and regularly clashed with the selectors and members of the board.

He claimed that since it was the captain’s head that lands on the chopping block when the team does not do well, the captain should have the most say in selecting the team.

Khan would often throw away and reject touring squads selected by the selectors, and refuse to play if his recommendations were not entertained in selection matters. This attitude bore both fruit and frustration.

For example, he fought hard with the board to get in players like Abdul Qadir (who would go on to become a world-class spinner). He also dotingly nurtured fast men like Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis and Aaqib Javed who went on to lead a fast-bowling revolution in Pakistan in the 1990s.

However, the attitude also saw him disastrously bet on some losing horses. He stuck with batsman, Mansoor Akhtar, at the expense of more deserving players in spite of the fact that Akhtar, albeit talented, clearly lacked temperament for international cricket.

He also gave an undeserving run to average fast bowler, Zakir Khan, just because Zakir had become a close buddy of his.

But the board could not do much about Khan’s tantrums as long as he had the backing of the team, was performing well as a player, and producing unprecedented victories.

For example, it was under Imran that the team notched its first ever Test series wins against England (in England) and against India (in India) – both in 1987.

No player, except his vice-captain, Javed Miandad, dared disagree with him, and the selectors and board officials mostly did what he told them to.

He would also often exhibit his anger on the field at players he thought weren’t giving their all, and the spectacle of Khan admonishing players with some choice Urdu and English abuses became a common sight.

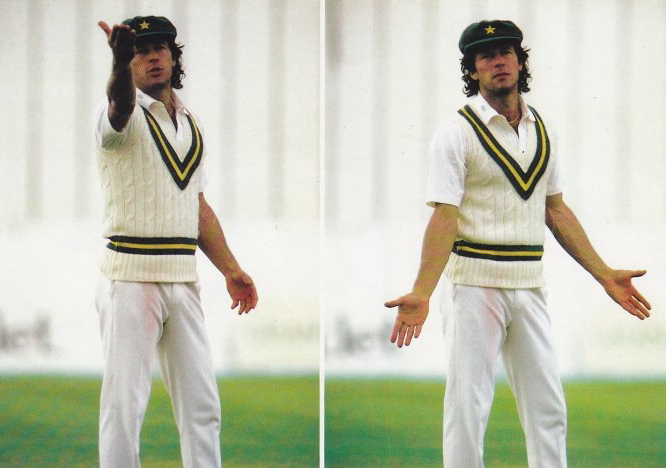

No wonder then that one of Khan’s heroes was former Australian captain, Ian Chappell. Like Chappell, Khan regularly applied tactics involving mind games.

For example, when he managed to bring back Abdul Qadir from oblivion for the team’s 1982 tour of England, he told the British press that there has never been a trickier leg-spinner than Qadir. He then asked Qadir to grow a ‘wizard’s goatee’ so he would look like a mysterious magician.

During an ODI tournament in Australia in 1986, Khan advertised all-rounder, Manzoor Elahi, as being ‘perhaps the hardest hitter of the cricket ball in the world.’ Of course, he wasn’t.

In 1989, while playing an international ODI tournament in India (that Pakistan won), Khan (to distract the Indian team), told the press that the issue of Kashmir should be resolved and settled (between India and Pakistan), on the cricket field!

Players found him to be uncompromising and stern on the field, but also remember his captaincy to be a ‘very fun period’ in their careers.

Khan was famous for being a ‘party animal’ who encouraged his team to live it up, especially when it came to women.

However, his dictatorial on-field disposition and off-the-field antics did not always go down well with some players.

Qasim Omar, a dashing middle-order batsman, after he was admonished by Imran in the dressing room for getting out playing a rash stroke in Australia, returned to Pakistan and accused Khan and his team of being ‘compulsive hashish smokers’ and for ‘regularly bringing women into their hotel rooms.’

Younis Ahmed, whom Khan had brought back into the side in 1987, accused Khan of offering him a hashish-filled cigarette at a nightclub in India.

Khan finally wrapped up his career by leading Pakistan to win the 1992 World Cup in which his vice-captain, Javed Miandad, and he played pivotal roles.

Imran retired immediately after the World Cup, aged 41. After getting married, he entered politics as a ‘born-again Muslim.’

Captaincy Record (1982-84/1986-88/1989-92):

Tests: 14 won, 8 lost, 26 drawn.

ODIs: 75 won, 59 lost, 1 tied, 4 no result.

Wasim Akram

Ace fast bowler, Wasim Akram, made his debut in Test cricket at the age of 18 in 1985. He had been plucked by Javed Miandad to tour New Zealand, but it would be Imran Khan who would go on to nurture and train him into becoming one of the game’s finest left-arm fast bowlers.

With Waqar Younis and Aaqib Javed, Akram unleashed a fast bowling revolution in Pakistan that also saw the emergence of genuine pace men like Shoaib Akhtar, Mohammad Zahid and Mohammad Sami.

Akram’s march towards captaincy, however, was controversial. When he was made captain in 1993, Javed Miandad, who had replaced Imran Khan as skipper in 1992, accused Imran of inciting Akram and his fast bowling partner, Waqar Younis, against his captaincy.

Akram’s first stint as captain ended in a disaster. After squaring a closely fought ODI series in the West Indies, Akram and at least three other Pakistani players were arrested from a beach in the Granada Island, for publically smoking marijuana.

The incident almost turned into a serious diplomatic row between the Pakistan and Granada governments till the players were finally released for the Test series which Pakistan promptly lost 2-0.

In spite of the incident, Akram was retained as captain. However, he soon faced a full-blown rebellion from ten players led by Waqar Younis and spinner Mushtaq Ahmed after the 1994 series against Zimbabwe.

The rebelling players accused Akram of being rude and abusive and exercising nepotism. Akram was ousted and replaced by Salim Malik.

After a few players turned whistle blowers and accused Malik of indulging in match-fixing, Malik was removed by the board and replaced with Ramiz Raja.

Raja soon gave way to Akram’s return as skipper in 1996.

His second stint as captain saw him leading a formidable team of batsmen, all-rounders and fast bowlers, and it was under Akram that Pakistan became one of the most powerful cricket teams of the 1990s.

Though Akram continued to perform well as a player and capably led the team, his dream of winning the World Cup never came true. He was captain during the 1996 as well as the 1999 World Cup events.

In 1996, after leading the team into the quarter-final of that year’s World Cup, Akram suddenly dropped himself from the squad due to a muscle injury. The match was against arch-rivals India (in India).

After Pakistan lost the game and was ousted from the tournament, Akram’s decision was severely criticized by the media and fans alike, and some even went to the extent of accusing him of throwing away the game for money.

Akram’s home in Lahore was also attacked by angry protesters.

But Akram’s third stint was extremely brief (but in which he led Pakistan to its first ever white-wash against the West Indies in a 3-Test series in Pakistan).

He soon decided to step down after accusations of match-fixing and nepotism continued to chase him. He was first replaced by Saeed Anwar and then by Aamir Sohail, both of whom did not last long.

In 1998-99, Akram was back for his fourth stint as skipper. He proved his growing maturity as a player and captain after leading Pakistan in a tense series against India (in India) when political hostilities between the two countries had reached a new peak.

Facing hostile crowds, threats from extremist Hindu groups, and a hawkish Indian media, Akram’s team won two of the three Tests that were played on the edgy tour.

During the 1999 World Cup Pakistan under Akram galloped its way to the final of the tournament where it was defeated by Australia.

In 2000, Akram relinquished the captaincy and in 2003 retired from the game.

Cricketers and experts around the world have continued to praise Akram as being perhaps the finest left-arm fast bowler the game has ever seen.

He (along with Waqar Younis), led one of the most feared and potent fast-bowling attacks in world cricket in the 1990s that included Aaqib Javed, and (from the late 1990s), Shoaib Akhtar and Muhammad Zahid, all capable of bowling deliveries over 90 mph.

But in spite of the fact that during his second and fourth stints as skipper he managed to largely realise and utilise the unprecedented talent available in Pakistan cricket in the 1990s, and convert it into becoming a powerhouse, many experts still hesitate to call him a great captain.

Akram led by example, but the accusations that he faced of match-fixing, gambling and throwing tantrums on the field against his players have sullied his reputation as a captain - even though the match-fixing allegations were never fully proven (as they had been against players like Salim Malik, Mohammad Azaruddin, Hansie Cronge and a few others).

Also, on many occasions, he would simply announce his unavailability to play in a Test series for Pakistan, opting instead to play county cricket in England.

His critics also point out that his job as captain was made easier by the fact that in the 1990s Pakistan cricket was regularly producing some outstanding batsmen, bowlers and all-rounders. However, the same talent was also available to stop-gap skippers like Ramiz, Anwar and Sohail, all of whom could not transform it into producing the kind of results Akram’s captaincy was able to.

Akram’s greatest achievement in this regard remains to be Pakistan’s tour of India in 1998-99, where Akram amicably led the team on a politically tense and somewhat hazardous tour.

Captaincy Record (1993-94/1996; 1997-98/1998-2000):

Tests: 12 won, 8 lost, 5 drawn.

ODIs: 66 won, 41 lost, 2 tied.

Inzamam-ul-Haq

Purely as a batting talent, Inzamam is rightly placed alongside three of the greatest batsmen produced by Pakistan: Hanif Mohammed, Zaheer Abbas and Javed Miandad.

Just like Zaheer and Miandad, Inzamam too was a natural when it came to batting, something that cannot be said about him as a captain.

In fact, he was an unlikely candidate in this capacity, having an extremely laid-back personality and not much experience as a captain even across his local first-class career.

But certain events conspired to not only make him a more responsible and serious person, but also prompt the cricket board to actually hand over this once lazy, relaxed but highly talented batsman, the captaincy.

One of these events was the way he lost all form during the 2003 World Cup in South Africa and produced a series of low scores, as the Pakistan team crashed out of the tournament.

The (albeit erratic) powerhouse that the Pakistan team had become in the 1990s had clearly begun to crash, and by the time the team exited from the 2003 World Cup, it at once lost a number of players that had helped it become this powerhouse: Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis, Moin Khan, Saqlain Mushtaq, Saeed Anwar, Aamir Sohail, etc.

Inzamam’s position in the team also became doubtful and he, along with other remnants of that era, Rashid Latif and Shoaib Akhtar, seemed to be on their way out.

Though the selectors brought in a number of new players into the side, they also decided to stick with Rashid Latif (who was made the captain) and Inzamam. Later, Akhtar too was recalled.

Latif’s captaincy did not last long and the selectors decided that an experienced player like Inzamam should be handed over the captaincy because much of the new team was packed with youngsters.

Inzamam, who had made his Test debut under Imran Khan in 1990, had experienced the dizzying highs and sudden lows of the Pakistan cricket team across the 1990s and early 2000s. He had witnessed the emergence of outstanding talents (of which he was one), and the team pulling off some unbelievable victories in the 1990s.

At the same time he had also seen vicious power struggles between players over the issue of captaincy, angry player rebellions, accusations of match-fixing, drug taking, womanising and infighting.

He knew well the erratic, volatile and perplexingly flamboyant culture of Pakistan cricket when he was handed the captaincy to lead a team that was now mostly made-up of young players.

Inzamam did not have an urbane and aristocratic background that great captains like Kardar or Imran had; nor did he possess the street-smarts and sharpness of captains like Javed and Mushtaq Mohammed.

Also, though he was a contemporary of Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis, unlike them he did not readjust his petty-bourgeoisie disposition and turn himself into a more cosmopolitan entity.

He held on to his small-town moorings even though he was a willing participant in many of the team’s raunchy off-field activities (in the 1990s).

The question was how would this easy-going gentle giant face the rude, awkward challenges that the country’s cricket culture often throws at captains?

Instead of adjusting his demeanor to suit the ways of this culture, Inzamam decided to change the culture itself.

Cleverly, he decided to use religion as a tool, in spite of the fact that till he joined the large Islamic evangelist outfit, the Tableeghi Jamat (TJ), in early 2003, Inzamam had not been a very religious man.

Though respected in the team as an outstanding batsman, Inzamam, initially, was not entirely accepted as a captain by the team. But backed by his Tableeghi colleagues and mentors, he went about constructing a whole new culture in the team that would be more suited to his new-found temperament and world-view.

The TJ as a movement, though apolitical, is highly exhibitionistic and ritualistic. It were these two aspects of the movement that Inzamam used as a way to instill discipline in the team and to also keep at bay dissent from the players.

Regular prayers and gatherings were organized and the players lectured by TJ men on the virtues of faith.

The young lot soon fell in line believing that failing to do so may isolate them in the squad or even cost them their place in the team.

Players were also encouraged to openly display their religiosity and many of them hailed the team’s new-found culture. But it wasn’t only the players that did that.

After the team under Inzamam began to settle down and produce impressive results, the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) and the team’s South African coach, late Bob Woolmer, also began to praise Inzamam’s tactics.

They agreed that these tactics had not only changed the team’s culture for good, it had stabilised Pakistan cricket (after the 2003 World Cup debacle) and made the players more hard-working and disciplined.

Inzamam’s captaincy reached its peak when his team toppled the Ashes-winning English side 2-0 in 2005-6, and then went on to not only square the hard-fought Test series against India (in India), but pulverise the Indian side 5-1 in the following ODI series. Inzamam himself was in devastating form as a batsman during these series.

By 2006, however, Inzamam’s tactics had begun to wear thin. By then the team was regularly going on tours with an entourage of famous TJ members and preachers. As his insecurities as a captain grew, so did his demands for a show of religiosity from the players.

Some players began to react negatively. His vice-captain, Younis Khan, though a religious man (who kept his faith private), never fell in line with Inzamam’s demands.

Former PCB chief, Shahryar Khan, claims that Inzamam was never secure as a captain and was weary of Younis whom he thought was out to usurp his captaincy.

Khan also suggested (in a 2013 book), that Inzamam kept talented players like Misbah-ul-Haq and Saeed Ajmal out of the team. According to Khan, Inzamam thought that Misbah’s cosmopolitan, world-weary and liberal disposition might threaten his (Inzamam’s) regime based on a particular brand of the faith.

But it was tear-away fast bowler, Shoaib Akhtar, who reacted the most aggressively against Inzamam’s devices. Being a throwback of the more flamboyant and extroverted era of Pakistan cricket, Akhtar regularly clashed with Inzamam and refused to toe the new party line.

Inzamam’s captaincy finally collapsed during the 2007 World Cup. Officials touring with the team complained that Inzimam and other players who had joined the TJ were putting more effort in trying to find fresh recruits for TJ than in playing cricket.

Inzamam retired from the game in 2007 and became a full-time preacher with the TJ.

The most remarkable thing about Inzamam’s captaincy was how seamlessly he managed to change the culture of the Pakistan team, smartly using religion and then actually succeeding in infusing a sense of stability and focus back into a fragmented, young squad.

However, apart from the fact that this tactic isolated some of the players, it eventually collapsed under its own weight.

In one of his many outbursts at the time, Akhtar had claimed that the exhibition of piety from most players was based on hypocrisy and only practiced by them to remain in the captain’s good books.

He seemed to have judged his colleagues correctly because Inzamam might have diverted players from drinking and womanising, the culture of piety that he constructed only managed to replace these ‘sins’ with more damaging ones.

After his retirement, the same players were exhibiting unabashed greed and some of them could not find anything wrong in getting money from bookmakers for spot-fixing.

Then the same players who would so willingly take part in Inzamam’s demonstrations of public piety began to conspire against each other for the captaincy slot.

Inzamam’s exit from the game was a sad affair. A brilliant stroke-maker and a surprisingly influential skipper had to exit with tears in his eyes and fend accusations of misusing religion to promote favoritism and nepotism.

Captaincy Record (2003-2007):

Tests: 11 won, 10 lost, 9 drawn.

ODIs: 55 won, 33 lost, 3 no result.

T20: 1 won.

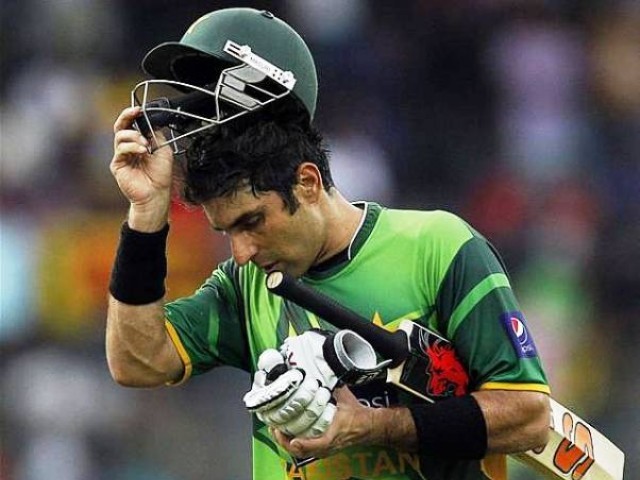

Misbah-ul-Haq

As captain Misbah-ul-Haq is unique. Not only in the context of Pakistan cricket, but also world cricket. He might be the modern-day game’s first war-time captain.

Consider: When he was handed over the captaincy in 2011, Pakistan was already facing a terrible existentialist crisis. Religious extremists were bombing mosques, shrines and schools and slaughtering civilians, cops and soldiers.

Pakistan was on the brink of a civil war that today has become a forgone reality, as the government, the military and the country’s ravaged polity prepares for an all-out war with the extremist insurgents in the country’s mountains and cities.

Misbah’s captaincy is also unique because he has never led the Pakistan team in Pakistan. No foreign team has been willing to tour the country ever since extremists attacked the Sri Lankan squad in Lahore in 2009.

All of Misbah’s games as captain have been played, won, lost and drawn on foreign soil. Teams have to do well outside of their own countries, on foreign tours and in front of foreign crowds, to fully prove their prowess. That’s what the Pakistan team has been doing ever since 2009, especially after Misbah took up the captaincy in 2011.

When Misbah was handed over the captaincy, he was making his third comeback to the side (at the age of 36). He had made his debut for the national squad in 2001, but lost his place after losing form in 2002.

But in spite of the fact that he continued to perform well in the domestic circuit, he could not break back into the team till five years later when he was finally recalled in 2007. Though this time around he lasted longer and did well, he again lost form and his place in early 2011.

Between Inzamam’s retirement (in 2007) and Misbah’s elevation to the post of captain in late 2010-11, the team went through five captains! It could not play at home that kept plunging into extremist violence and political turmoil. The team was being torn from all sides by vicious infighting, multiple players’ rebellions and charges of spot-fixing.

What’s more, when a struggling, disoriented cricket board decided to hand over the captaincy to Misbah, he was in the process of making yet another comeback.

Asked to hold the fort till the board could come up with a more permanent candidate for captaincy, Misbah began to play his best cricket.

After consolidating his place in the team again, Misbah began to undo whatever that was left of the culture weaved by Inzamam.

Cricket alone became the devise to measure a player’s worth. Misbah also tried to subdue the team’s reputation of being highly unpredictable by promoting a more watchful and cautious approach towards the game.

He was vehemently criticized for this by some critics and fans, but quietly he managed to pull the team out of the doldrums and make it begin its slow march upwards in world rankings.

Misbah’s steady approach and tactics not only encouraged the curbing of flamboyant batting skills for the benefit of a more cautious attitude, it eventually (and consequentially), made the role of spinners become more prominent than that of the quick bowlers.

This was a clear break from the past in which for almost three decades the Pakistan team had largely banked on fast bowlers to win matches. Under Misbah, the spinners took precedence, and this precedence saw him introduce one of the finest and most innovative off-spinners in the game today: Saeed Ajmal.

Misbah’s tactics bore fruit ever so slowly but surely. However, on the way, he also managed to gather some highly vocal critics who seemed disturbed by his cautious attitude and the way he was dismantling the team culture designed by Inzamam and then by the short-term captains that followed him.

Nevertheless, within two years, Misbah had notched up more Test and ODI victories under his belt than most Pakistani captains. He was able to establish himself as a highly respected and liked skipper in the team by both the seniors and especially by the younger players, all of whom treat him like a father figure.

His batting average as a captain has remained to be over 50 and he has notched up more fifties and hundreds as a skipper than he was able to at any time in his career.

Teams under good and influential captains begin to reflect the personality of that captain. Mushtaq and Imran’s teams reflected the daredevil and flamboyant ways of their captains, and same can be said about the team under Akram.

Inzi’s team became as introverted and conservative as Inzamam had become. The current team under Misbah seems to be as down-to-earth, stoic and determined as the man himself. Also, like Misbah, the team does not wear its religion on its sleeves. Faith has once again become a strictly private matter in Pakistan cricket.

With a stoic, quiet but secretly ferocious determination, Misbah has managed to become one of the few great captains that Pakistan cricket has produced.

And it won’t be wrong to suggest that with his advancing age, the criticism that his tactics had to face, and especially, the kind of circumstances he as a Pakistani is faced with both at home and abroad (with all the violence and turmoil in his country), he had to beat mightier odds to become a great captain compared to his contemporaries in this elite group of cricketers.

Captaincy Record (2011-Current):

Tests: 12 won, 7 lost, 8 drawn.

ODIs: 36 won, 26 lost, 2 ties, 1 no result.

T20: 6 won, 2 lost.