At a recent conference held at the Alliance Francaise Karachi on French Contributions to Pakistan Studies, I learned about all the amazing research in Pakistan conducted by French paleontologists, archeologists, sociologists, political scientists and biologists. It's heartening to know that for them, Pakistan is not seen as a hotbed of terrorism but as a rich cradle of ancient civilisation, encompassing the Indus Valley and also the millennia preceding it.

Gregoire Metais, a French paleontologist, talked about the investigation into biodiversity in the early Paleocene era. The fact that the Indian continent broke off from Africa and "drifted" in the ocean for eons allowed very specific groups of flora and fauna to develop in isolation – a great opportunity for paleontologists who want to test the “Indus Raft” theory first developed by Krause and Maas in 1990.

The French palaeontologists are studying those same flora and fauna that Henry Thomas Blanford, a 19th century British geologist, explored around Ranikot in the Kirthar Range of southern Sindh. Metais, who is also a part of the Jean-Loup Welcomme group that discovered the bones of the Baluchitherium in Dera Bugti, described the beauty of the Khadro Shale, dark grey and green in colour, with gypsum thinly intercalated between it, and Bara Sandstone, inlaid with clay and kaolinite and white sand. He shared the discovery of seven-meter long snakes, crocodile, fish, and snake vertebrae, and a huge turtle shell 63 million years old: all hard science that looked like art and sounded like poetry.

A paper by the eminent archeologist Jean-Francois Jarringe described the amazing civilisation of Mehrgarh in Balochistan from 8000 to 500 BCE and described 35 years of excavations conducted there and in Pirak. Mehrgarh was part of the Neolithic era when people lived in mud-brick houses, surrounded by pine, juniper, poplar, elm, oak, cereals, graminaceous, reeds and moss growing around them in a humid, dense forest. Skeletons lay in graves, legs flexed and frames oriented east to west, surrounded by pendants and jewellery made of lapis lazuli and turquoise, the skeletons of goats and sheep, as well as tools and pottery. Jarringe and his team also discovered traces of cotton and copper, the earliest use of both in the entire Indian subcontinent.

The later period of Mehgarh, saw the emergence of painted pottery, clay-fired and glazed, gold beads, lost-wax copper objects, and terracotta artifacts. Dr. Jarringe found links between Mehrgarh and the Indus Civilization based on their water installations for sanitation and drainage. But it was at Pirak that the agricultural revolution of the world's first irrigated agriculture system, as well as the first crops of rice and jhovar, were discovered, and figurines depicting camels, horses and horse riders.

Dr. Aurore Didier and Dr. Roland Besenal told us about 20 years of archeological work in Makran, on the Baloch coast, also called Gedrosia by the armies of Alexander the Great who crossed there on their way back to Greece after their defeat in India. In the excavations in Shahi Tump, archeologists discovered circular hut basements and quadrangular buildings, and decorated pottery that has also been found in south eastern Iran. Most fascinating was the emergence of a “cemetery culture” where bodies were coated in red ochre and wrapped in reed mats for burial.

The work of the French Archeological Mission in Sindh, led by Dr. Monique Kevran for 25 years, began in the Persian Gulf, where Dr. Kevran found ceramics from Sindh in Oman. She came to Sindh to investigate and has stayed here ever since, working in Bhanbore. Her team, co-lead by Dr. Paul Wormser, discovered six different ports in the sea, which were outer harbours to protect and tax boats as they came to trade in the Indus Delta. The main port at Bhanbore is better preserved and considered to be an exceptional site from which to study the Indian Ocean trade, which runs from China to India to Yemen to the Persian Gulf, Iran, and all points west.

Michel Boivin spoke on the establishment of the Centre for Social Sciences in Karachi, where Pakistani students are trained in studying and researching culture and society in Pakistan and South Asia. Sophie Reynard spoke about GIS, the Geological Information System which is a next generation mapping tool that is digital and can incorporate all manner of information into a multilayered map; she showed us how all the shrines of Sindh are being mapped with information about the lineage of the Gaddi Nasheens, routes for the Urs of each saint, and photographs of the shrines from all angles.

Finally, Alix Phillippon, a PhD at Science-Po in Aix, spoke about French contemporary studies on Pakistan. She noted that most studies focus on the Middle East, with only two scholars at her institute focused on peripheral Muslim states – Turkey and Pakistan. Yet her work investigating the Sufi culture of Pakistan, including several books on the subject, illustrates that there is scope for many more scholars to conduct research in Pakistan.

Having met this dozen-strong team of the best and brightest that France has to offer in their fields, and listening to them as they spoke about their rich and important findings, and testified to the wonderful partnership with their local colleagues, I can't help but feel proud that Pakistan has so much to offer in terms of scientific and sociological research.

Yet it takes world-class expertise, scholarship, and training to unlock these treasures. I look forward to the day when Pakistan is able to produce a surplus of researchers and scholars of similar calibre. Until then, we should be inspired by the cultural cooperation between France and Pakistan that encourages their scholars to come to our country, fall in love with it, and dedicate their lives to revealing its mysteries to the world.

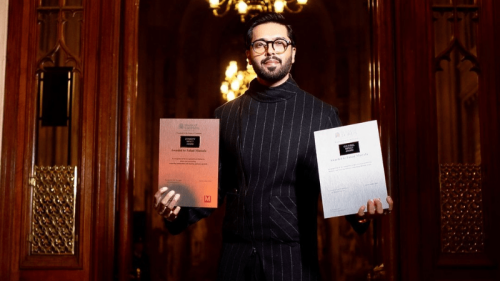

![Jean-Loup Welcomme [center] with Gregoire Metais [left]. –Photo Suhail Yusuf/Dawn.com Jean-Loup Welcomme [center] with Gregoire Metais [left]. –Photo Suhail Yusuf/Dawn.com](https://i.dawn.com/primary/2014/02/52f38c4d09dfd.jpg)