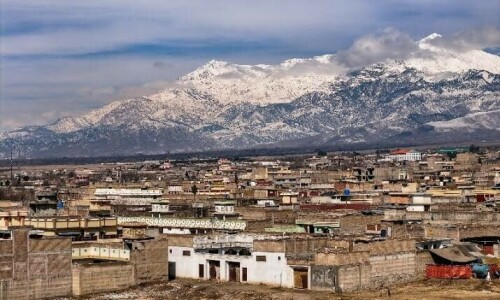

HOW does one tell of a calamity without turning it into a cliché, suffering into spectacle? We are immune, now, to the images, numb to the voices. Since 2005, there has been a debilitating run of natural disasters — of those man-made, we have lost count. Our compassion has long since turned into fatigue. The 2005 earthquake, we heard, was a national tragedy. What is this tragedy unfolding in North Waziristan? Is it Ours or Theirs, the innocents caught up in a war in a region that is so dangerous and so isolated you can’t even go there for disaster tourism? If the army allows you through, that is.

Read more: The IDP conundrum

What do I tell this young man from Mirali whose displaced family — two brothers and two cousins — has sought refuge in a village school in Bannu’s outskirts when he asks, hopefully, if the newspaper report will be able to bring him help? Do I tell him it is not a national tragedy, that no tragedy can shake the state’s numb conscience? He wouldn’t be here in the first place if that wasn’t the case.

Or do I tell him that speaking to a newspaper will highlight the trial he and hundreds of thousands of others face, stranded on the road between Bannu and Mirali, and on the streets of Bannu, looking for shelter in a town where the hotel rooms are all taken and the houses all rented for prices unimaginable for a young man like him?

But I have said that before, that talking to the media will help, to many in Abbottabad, Swat, Mohmand and Khyber, to Afghan refugees and local IDPs. Mere platitudes; a manipulation to get my story, an exploitation! All that media overkill has ever done is to shorten our attention spans. With disasters like grains of sand slipping through our fingers, we can’t seem to focus, to plug and prevent them. Worse, it has turned us, including the state, into numb voyeurs.

What do I tell my photographer friend who shows me the picture of a woman out on the Mirali-Bannu road, following a donkey laden with the pots and pans of her poor household, out walking on the burning road, lost and vulnerable because women like her have hardly ever ventured out of homes or villages, let alone been exposed to a world gone wrong? He says the sight made him cry. On the same road that day, I saw scores of the displaced, with thousands of heads of cattle; they had no money or transport to carry animals to safety.

Some of them have walked the road, all 60 plus kilometres of it, pushing unwilling cattle to an unknown destination — who will take their families in, let alone the cattle? They stop on the roadside to take a respite from the blazing heat and exhaustion, women sitting in ditches, men on the side squinting at the traffic of others like them. The number of people stranded on this road is staggering. A displaced person, an education officer who wants to remain nameless, says the displacement is “a calamity, a paradox”. “Look at our women here,” he says. “We gave them Kashmir, and this is what we get.”

“There was a child today, walking the road with his dog Moti [as in pearl],” says an AFP reporter as we eat dinner at a local restaurant. “His sandals were completely worn from walking the road, blisters on his feet. He said his family had died in a drone attack and people took his brothers and sisters to Bannu. But they wouldn’t take Moti along so he decided to walk instead. I asked him where would he stay and he said wherever Moti did.”

I went disaster reporting and ended by doing a bit of disaster tourism because I wasn’t allowed to report, to cover the camp or registration. Above a mound at the Saidgi registration centre where I find myself, watching the parched thousands pour in from Waziristan, I have a glass of cool Rooh Afza while listening to soldiers speaking into crackling walkie-talkies.

But all that I have is voices of the displaced: stories about air strikes, about jirga deadlines not kept, about children being brutalised and traumatised, of homes and lands left behind, with no idea about where they are headed and whether they’d ever go back home.

They have fumbled through the dark night and the day under a scorching sun, an exodus of man and beast trudging the road for more than 24 hours now. Among them I see a mad man, wearing the long, flowing dress of a Bedouin, walking barefoot on the burning road. He walks in the direction opposite to the one the displaced people take. I try to see poetry in that but there isn’t any. Stepping like he’s walking on coals, he walks back to Waziristan, to home. In the chaos of cars, trucks, tractor trolleys and pedestrians, he is a lone figure walking in the wrong direction. Nobody stops him, no one gives him water or food, or sandals for his singed feet. Nobody stops to tell him he can’t go back that way anymore.

Published in Dawn, June 22nd, 2014