BASS: Yashpal Mor grew up watching men in his village stay single rather than defy the rules of the traditional council which controls Indian rural life with an iron grip.

For as long as anyone can remember, families in a cluster of villages north of the capital have lived under two sets of laws, those of the government and another imposed by unelected but powerful men.

From marriage to property and even the wearing of jeans, all-male councils, or khap panchayats, have issued diktats that have controlled life in much of Haryana state, which borders New Delhi.

“I have seen many men in our village remain unmarried all their lives,” Mor told AFP in Bass, a village surrounded by lush farmland. “I don't want to share their fate. “Now, in a sign of major reform coming to a corner of the country steeped in tradition, the state's largest council has allowed couples from neighbouring villages, and even different castes, to marry.

For generations, the council had banned men marrying women from neighbouring villages or different castes, assuming that they were already related, and also because of caste prejudice.

With female infanticide rampant because of a preference for boys, eligible women were in short supply, fuelling an insidious “bride buying” industry and leaving many other men unmarried in a culture that prizes matrimony.

“The (new) decision that they have taken will have a lot of benefits,” said Mor, 24, whose parents are now looking for a bride, a task made easier by the lifting of the ban.

“Earlier there could be no marriage alliances but now it will start happening. So it's really something to be happy about,” he added.

'Kangaroo courts'

Often embroiled in controversy, khaps have been branded “kangaroo courts “for their punishments, including fines but also horrific violence.

They have been blamed for provoking honour killings, public beatings and even fuelling the buying of brides.

In some cases, khaps have ordered young couples be stripped naked, thrashed in public and even lynched by mobs for defying their orders on relationships.

Council head Inder Singh, who led the push for reform, said he was trying to “erase the bloody past” of khaps, which dominate swathes of mainly rural, northern India, and are often bastions of caste prejudice.

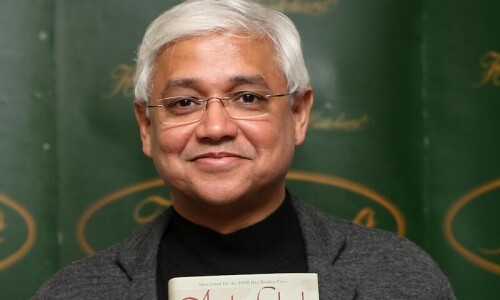

|

| In this photograph taken on May 5, 2014 Inder Singh More, the head of the 42-village Khap Panchayat or local village council, prepares for an interview with AFP at his residence in Hissar district of the northern state of Haryana. — Photo by AFP |

“We began our efforts some three years back to get rid of the caste bias. I went to every village and tried to build a consensus,” said Singh, 78, at his two-storey house in Bass.

“There was a lot of resistance initially. Some five per cent are still against but I am glad the majority have agreed,” he told AFP.

Analysts hailed the move, announced in April, as a sign of easing khap control over villages.

Last year, girls were banned from wearing jeans and using mobile phones in a khap ruling issued elsewhere in Haryana for fear of fuelling sex crimes.

“It's a very important decision and it may prove to be a turning point for other khaps as well,” Anand Kumar, a professor of sociology in Delhi, told AFP.

“It will push others to become more reflective and liberal. It'll force them to think if they are really being fair to their sons and daughters,” he said.

According to those living in Bass and neighbouring villages, the marriage restrictions led to an acute shortage of “suitable” brides, placing intense pressure on families.

The problem was compounded by the fact Haryana already has one of the country's worst gender ratios.

This sparked a rise in “bride buying”, in which local men paid impoverished families in other parts of the country cash for their daughters, residents said.

Although there are no official figures, council head Singh estimated 10-15 “brides” were probably sold into each of the 42 villages under the khap's control in the last 10 years.

'I hate my life here'

Meera Deka is one such bride who says she was forced to leave her parents and her home in remote northeast Assam state when she was 25 after she was sold for 80,000 rupees to her now husband.

|

| In this photograph taken on May 6, 2014 Assamese villager Meera Deka poses in the yard of her home in Hissar district of the northern state of Haryana. — Photo by AFP |

“All day I am washing, cleaning and cooking. I don't understand their language, I don't like their food. I hate my life here,” Deka told AFP, as she tended buffalos in Bass.

Under the council's complicated rules, men were allowed to pay for a bride from another caste in another state - but were barred from having a consensual relationship with a woman from a neighbouring village.

Singh conceded the trend of “bringing in outsiders” as brides created numerous problems, with most of the women struggling to adjust.

“We realised it is better to have a daughter-in-law from a different caste but who is accustomed to our culture than bring in a complete stranger,” Singh said.

The move also addresses prejudices against lower castes, which are deeply entrenched in mainly poor, rural areas. Marriages between higher and lower castes are few in a country where despite rapid modernisation, tradition still holds sway.

And the reforms, which also include the appointment of the first woman to the khap, also go some way to softening the reputation of local councils, experts said.

|

| In this photograph taken on May 5, 2014 Indian social worker Sudesh Chowdhary (C), the first woman representative in the local village council, looks on during a meeting in Hissar district of the northern state of Haryana. — Photo by AFP |

With her days revolving around her many chores, Deka welcomed the new rules, saying hopefully fewer women would be forced to move to Haryana.

“I am glad women will no longer have to suffer like me,” she said.