It is perplexing to see the Pakistani currency in a tightly managed peg against the dollar despite the lowering of the interest rate in recent months.

Indeed, as a result of the sharp shift seen in global currency dynamics, the rupee on a real effective basis (x-rate estimated after taking into account bilateral trade shares and inflation rate differentials) has appreciated by more than 17pc since December 2013.

Interestingly, this sharp rupee appreciation move is even stronger than witnessed by the dollar over the same period. As such, when various emerging markets are scampering to weaken their currencies in order to generate economic growth, the rupee managed peg is transferring ‘economic growth’ to her trade partners via a stronger currency.

The global context in which this is happening makes things even more perplexing. As numerous central banks around the world have moved to ease monetary policy in recent weeks (with accompanying implications for currency dynamics), the spectre of ‘currency wars’ is back in focus. With interest rates in many economies currently very low the line between foreign exchange intervention via deliberate devaluation or monetary policy has become increasingly blurred.

On one side is the strength of the dollar which has gained 16.5pc (on a weighted basket basis) since mid-June 2014 as economic dynamics in the world’s largest economy decoupled from rest of the world. Here, clear strength of the US economy against anaemic economic growth and deflation in the euro area leading the European central bank to deploy quantitative easing, Chinese growth slowdown and after-effects of Japanese monetary policy easing is a powerful driver behind the relentless rise in the greenback seen in recent months.

In the emerging markets too, the broad dollar rally has clearly manifested itself with a number of currencies reaching record low levels in recent weeks (for instance, Turkish Lira, Brazilian Real etc). Interestingly, the reaction of authorities in various developing countries to this latest bout of currency weakness has been markedly different to the episode seen during the mid-2013 to early-2014 period, when monetary policy/capital controls were directly used in a number of countries to stem the sharp and volatile depreciation pressure triggered by a perceived shift in Federal Reserve policy.

The rupee has peaked against the dollar and the main question mark now is around the shape/speed of the currency move rather than its direction

However, this time around the weakness in domestic currencies has been cautiously welcomed and in some cases encouraged against a backdrop of slowdown in domestic and external demand in a number of countries. For instance, in recent weeks, Singapore and China have modified their currency bands, South Korea has been talking about a rate cutting cycle, Indonesia and India initiated rate cutting while the latter has also been accumulating reserves by selling the local currency against the dollar to build buffers.

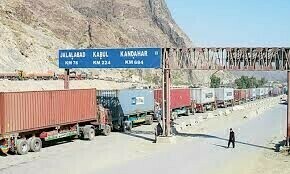

Around the world, developing countries are taking advantage of the rally in the dollar to strengthen their external sector via currency depreciation. In Pakistan, on the other hand, the external picture remains mixed at best with nominal export growth currently running roughly flat based on January data, while the trade balance remains depressed despite some uplift from lower energy bill. Deep structural issues — power shortages/law and order — continue to challenge exports but an over-valued exchange rate appears to be adding to this burden as well.

If the fundamentals don’t reverse soon, two scenarios will become increasingly likely. Under the first scenario, if the government recognises the above discussed important shift in global currency dynamics, then it can use the ‘strong’ rupee to build further reserves and in the process, let the currency depreciate gradually in coming months (especially against the euro and the yen).

Under the second scenario, the build-up of imbalances will only worsen going forward as Pakistan’s major trade partners keep their currencies weak against the dollar leading to further pressure on the external side. This will eventually show up in a sharp period of depreciation once the positive impact of lower oil prices pass through.

Specifically, the currency’s over-valuation (visible in the real effective x-rate metric) and the resulting loss of competitiveness is likely to keep pressure on the external sector. This in turn will lead to pressure on the exchange rate in coming months. Finally, the reduction in domestic interest rates and the accompanying increase in domestic money supply as the rate hiking cycle starts in the US later this year will also blunt rupee’s yield advantage. Indeed, whichever scenario shapes up, one thing is clear: the rupee has peaked against the dollar and the main question mark now is around the shape/speed of the currency move rather than its direction.

Published in Dawn, Economic & Business, March 2nd , 2015

On a mobile phone? Get the Dawn Mobile App: Apple Store | Google Play