Parsis in Pakistan: Beloved but left behind

|

By Ahmed Yusuf

There was a royal feast at Aunty Villy Engineer 96th birthday. There was cake, and there was suuji ka halwa too. Everybody inside the Parsi General Hospital came to the party; Aunty Nargis Gyara, Aunty Khorshed Malbari and her sister too. Then there were Gulbanoo Bamji and Homy Gadiali, secretaries of the hospital. The men from the male ward came too. So did the doctors. And the physiotherapist. All the attendants too. Nobody wanted to miss it.

And why would they? After all, Aunty Villy is a superstar. Some boast that the 96-year-old Parsi woman was the first lady admiral of the country’s navy. But Aunty Villy dampens all such talk. “You know I don’t like boasting,” she says dismissively.

Outside her ward, in the corridor, the evening shuffle begins to pick up. It is almost time for tea, and some of the other women have already secured their place on the benches.

On one of the benches are Aunty Nargis and Aunty Ami Jeriwalla, two sisters, both spinsters, now living in one of the wards. “People ask us why you didn’t get married,” exclaims Aunty Nargis. “But then they tell us it was the best decision of our lives!” In terms of agency and choice, the Parsi women living in Pakistan were well ahead of their times.

The chatter in the corridor steadily grows louder.

Meanwhile, the men lodged in the adjoining male general ward are only beginning to rise from their afternoon slumber. Word has spread though that teatime is nigh; there is some shuffling on the beds and some make an effort to sit up. Nobody has bothered to switch on the television till now.

A little later, a male patient from a private ward heads outdoors to smoke a pipe. He chooses the entrance by the main road to smoke, while an attendant keeps him company. The noise and smog around him don’t seem to matter; this is an evening ritual that must be performed.

|

The 30-bed Bomanshaw Minocher-Homji Parsi General Hospital, commonly known as the Parsi General Hospital, is a pre-Partition facility that was built to provide subsidised quality healthcare to poor Parsis and was run by the Bomanshaw Minocher-Homji Parsi Medical Relief Association.

Although the hospital was inaugurated in 1942, the association expanded the premises as needed. “We didn’t have the 30 beds that you see today, we just had three rooms. We didn’t have the population either that necessitated the setting up of a larger facility,” explains Homy Gadiali, secretary of the association. The infirmary, for example, was set up in 1965.

But the story of the Parsi General Hospital and its inhabitants perhaps mirrors the fortunes and fate of the Parsi community in Karachi.

They were once the crème de le crème of Karachi society and polity, with the city’s first mayor, Jamshed Nusserwanji, also hailing from a Parsi family. Those admitted to the hospital today are all septuagenarian, octogenarian or nonagenarian; many would have seen Nusserwanji and witnessed how the city evolved too.

|

|

| Photos by the writer |

But over time, the number of Parsis in Karachi has dwindled. Gadiali estimates that the Parsi community has shrunk from about 5,000 at Partition to about 1,200 people now. Much of this decline in numbers is attributed to migration and birth rates.

“Even though Parsi people live long lives, deaths were never replaced by a corresponding number of births,” explains Gadiali. “There was a time when people didn’t get married because there was a lack of housing facilities for them. Now, much of the community-run accommodation facilities are lying vacant.”

While the Parsi community set up trust funds to take care of their own, the community saw major demographic shifts within. In pursuing their careers and sometimes due to insecurity, the younger generations began migrating from Pakistan. The older ones were left behind, sometimes out of necessity and sometimes out of choice.

“It is difficult to travel with an ill parent or parents if you are migrating from Pakistan,” says Gadiali. “There is the obvious tension of travelling, sometimes with kids, handling them, looking for a new home, settling down in a new place and other teething problems. Many people can’t afford to take an ill parent along, because medical costs abroad can be extremely prohibitive.”

It is because of this dynamic that the many of the 30 beds in the hospital are now occupied by elderly people whose families have either migrated or who have nobody to take care of them at home or even those whose families cannot afford caretakers able to tend to them around the clock.

In its essence, the Parsi General Hospital also doubles up as an old home facility. The hospital is a safe space for many Parsi elderly, because a sense of community and belonging pervades the hospital environment. Room rents are minimal in general wards; only Rs300 are charged per day. The maximum daily cost is Rs1,750 for a private ward. Four meals are served to patients every day. Every now and then, some Parsi families also send food and fruits over.

Many families arrange live-in attendants for their loved ones, but those who can’t still rely on the hospital without much hesitation. In the infirmary, for example, an elderly woman in her 90s is taken care of by an attendant around the clock, except at 7pm every evening, when her son arrives from work. The woman’s memory is failing, but what she knows is that her son will have dinner with her every evening.

Life is assisted for many old Parsis but it is normal too; there are no qualms about accepting medical help, nor does it hurt anyone’s ego or sense of self in doing so. Their age brings with it peculiar ailments; the majority admitted on temporary basis have arrived due to fractures, weak muscles, and other orthopaedic complaints. The hospital employs a physiotherapist; he helps patients practice movement exercises and walk.

“We might have a small staff, of doctors and attendants, but what we ensure is that those admitted here will be taken care of. There is an element of trust and reliability involved, since those living abroad need to know that their loved ones are safe,” says Gulbanoo Bamji, joint secretary of the hospital.

From time to time, donations received by various trusts and individuals have allowed the hospital to expand and keep the existing operations running smoothly. Gadiali regrets that it is only a matter of time before none of it will be needed, since there wouldn’t be many Parsis around to begin with.

But for those who live at the hospital, there is much to be grateful about, much happiness to share and many more days to look forward to. There are no regrets of being left behind. There is only an acknowledgment that those in the hospital shall take care of each other, in the best ways possible. This year, they celebrated Valentine’s Day too. They sang songs together, they ate extra snacks too, and they chatted for hours on end.

“All you need is three magical words,” says Aunty Villy, “Thank you God. Thank you for the gift of another day to serve you better. If you run into mishaps, know that ‘this too shall pass.’ Life is what you make it, so make it nice and bright.”

The writer tweets @ASYusuf

The original shippers

As Karachi’s oldest shipping moguls, the Cowasjees have many stories to tell about the city by the sea and its port

By Madeeha Syed

There is an old sign from the Colonial era that reads ‘Cowasji’ outside the brick structure of the Cowasjee building in Karachi’s port area, Keamari. Inside, 86-years-old Cyrus Cowasjee’s office still maintains its rather vintage design and interior. There are portraits of several generations of Cowasjees adorned on the walls: his father Rustom Faqir Cowasjee, his brother Ardeshir Cowasjee, and a grand uncle, Hirjibhouy Cowasjee, who died very young.

The Cowasjees have been a part of the city by the sea since 1883.

“I think they came by boat,” says Cyrus Cowasjee, referring to his ancestors. He is the ‘youngest’ board member of Cowasjee group, the oldest shipping company in Pakistan. “They came on an old sailing ship from Bariawa from the West Coast of India,” he adds.

“We started off as coal and salt merchants and then moved on to ship owning,” he says, “it went on until last year when we shut down the business.”

After 107 years of being in business, this legacy of Karachi too has come to an end. But equally, it does give him a lot of stories to tell.

“I started work after leaving college in late 1946,” relates Cowasjee. “Back then, we could cycle from home to the office in 10 minutes! We lived near the Cantonment station at the time. The first project I was assigned to by my family was to dump ammunition into the sea. Isn’t that strange? Why should we throw ammunition into the sea?”

Why indeed, I wonder.

“Just before Partition, the British government decided that there was too much ammunition in the country. And since there was friction among the people, the fear was that it would escalate into conflict,” he explains. “We were given the responsibility of dumping 15,000 tonnes of ammunition. It was live ammo and any mistake would make it blow up. That was my first experience.”

A young Cyrus Cowasjee managed to learn the ropes of the business by 1947; the rest was for him to enjoy and savour.

“Immediately after Partition, we worked at the port and there were labourers of every community. In those days, only women would work on the coal on the ship. Once a woman came to me and told me another woman was in labour in the hull of a ship! I went down and found that a child had just been born,” he narrates.

“There were no clean clothes for the child to wear. There was no way to get her up, so after covering her in a piece of clothing we had to lift her up in a tub. We’ve progressed to a point where this doesn’t happen. But since then, minorities have been slowly pushed out.”

|

Did the Parsi community ever face any kind of major discrimination, I ask.

“Discrimination? Not really,” he says, remembering an incident in early 1948. “Back then there were only two shipping companies. It was our turn to buy ships. The other side came to the government and says we are representing one million Muslims and this is only one Parsi family so we should get the priority.”

The minister at the time gave it to them out of turn.

“My father went to Jinnah to complain. He went with Jamshed Nusserwanjee. Jinnah replied, ‘Mr Cowasjee, this was the best government I could give you. The next one is going to be worse.’ So forget about it. So what if the Paris community is small? We are entitled to that port around the ship. That was early 1948. Such minor things go on but nothing major.”

And what of the community at large?

“The community is safe. Because it’s so tiny, it’s out of people’s minds. It’s not a threat to anyone because we don’t convert others so the orthodox Muslim doesn’t feel threatened in any way,” he responds. “Everybody has to move with the times and assimilate with the majority communities. They make do and live in their colonies. My children now have more non-Parsi friends than Parsi friends. It’s a good thing in a way.”

The community has strict rules against converting or including ‘outsiders’ into the community. “The original objection was that if you let non-Parsis become Parsis then they would get access to the trust funds!” laughed Mr Cowasjee, “There was a very serious case in the Bombay High Court, whether that should be allowed or not allowed. We were far more affluent as a community. The money in the community was so much more as compared to the other communities.”

He’s referring to the case in 1906 regarding the right of the French wife (Susanne Brier) of Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata ‘to be initiated into the Zoroastrian religion and to gain access to religious and charitable institutions, including those maintained by the Panchayat: for example, funeral grounds and temples.’ Not surprisingly, the verdict went against her: she could call herself a Zoroastrian but couldn’t enjoy the ‘benefits’ the community provided for being a Parsi. Since then, no one has challenged this ruling predominantly because the term ‘Parsi’ is more ethnic, referring to descendents of those that followed the Zoroastrian faith and who migrated to India in the 1800s.

But the draining of Parsi brainpower out of this country is of great concern for Cowasjee.

“It’s slowly going down. It’s going down very fast! Younger people don’t feel there is much of a future here, that’s why. They usually come back when they get old because it’s not easy living in countries abroad once you get old. Basically, it’s like an elephant coming back to die.”

India’s Parsis grapple with tradition

The Parsis may have continued endogamy to safeguard their identity but today they confront a dwindling community

By Raksha Kumar

“It is not hidden, but it is so seamless that it goes unnoticed. That reflects how the Parsi community has quietly sunken into the societal fabric of India over the past 1,500 years,” said the 74-year-old Cyrus Dajee, talking about the Parsi Colony — a bunch of buildings owned by the Parsis in Dadar, Mumbai.

|

Unlike the other Parsi Colonies in this coastal city, it is not bound by a wall or fence that would isolate it from its surroundings.

The corners of his starched white kurta flapped in the moist evening breeze, a black oval cap sat comfortably on his head. He spoke with ease and confidence, even though age had made his voice slightly shaky. Wielding his walking stick was his favourite distraction, I noticed.

It was 2013 and I was strolling in a garden in the Dadar Parsi Colony, when Dajee approached me and struck up a conversation. We just sat on a nondescript bench in the middle of the worn-down park. When asked for details about his religious community, he said, “I am a nobody; there are those who run the religious bodies, ask them.”

But, in time, he went on to tell me all about it anyway.

“Don’t you think we only talk about the glorious past of the Parsis?” I asked. “We rarely talk about the turbulence that the community is going through.”

“Well, you certainly haven’t spent enough time in a Parsi household, then!” he smiled. “All we talk about over dinner is the decadence in the present generation.”

When I said turbulence, I didn’t mean that the young were at fault, I pointed out. But, Dajee didn’t seem to concur. “When we were young, Zoroastrianism meant something to us — a religion, a way of life,” he began his long monologue. “Today, the religion and its practices are lost,” he shook his head disapprovingly.

According to several accounts, the Parsis first came to the subcontinent from Persia in the eighth or 10th century, in order to avoid persecution by the Arabs who were conquering that country.

|

The Parsis follow Zorastrianism, a religion based on the teachings of Zoroaster. According to the 2001 census, there were a little less than 70,000 Parsis in the India. More than half of them, about 45,000, live in Mumbai. And about one third of those live in the upmarket Dadar Parsi Colony.

Even though Dajee began his monologue with the rehearsed contempt for the younger generation of the faith, his views on the problems Parsis face, gradually became more nuanced.

Any community that imposes rigid rules on its people relentlessly is walking straight into its end days, he said. “Remember,” he continued, “the Zoroastrians came from the Iran of yesteryear where the pressure to convert to Islam was really intense. Therefore, the Parsis began to marry within the community. I think when they arrived on the shores of India, they were scared of the caste system in this country. They feared the upper castes would not let them be one of them, and they didn’t want to be relegated to the lower castes. So, they were left with no option but to continue their tradition of endogamy.”

I nodded at his complex historic reasoning. “But, why should the young girls of today be forced to marry within the dwindling community?” he asked rhetorically. When a woman marries outside the community, her children are not considered Parsi.

|

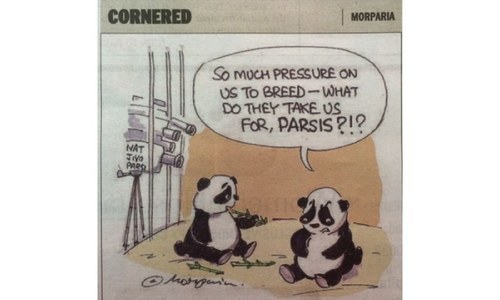

| Advertisements run by Parsi organisations such as the one on the left returns to the original legend of the raja of Sanjan and Parsi elders to encourage procreation.Cartoonist Hemant Morparia takes a dig at the campaign through a drawing published in the Mumbai Mirror on November 14, 2014 (above). |

Dajee’s granddaughter is 28 and works as a business analyst at a technology firm. While Dajee would love to see her married off to a Parsi following all the religious ceremonies, the way he and his wife of 50 years did, he understands that there might not be a suitable match for his outgoing, intelligent granddaughter within his small community.

“After all,” he waved his hand at no particular thing, “religion is only one of the identities of a person, isn’t it? My granddaughter is a professional, she is a confident global citizen who also happens to be a Parsi,” he said.

Such lucidity of thought is absolutely uncommon even in majority communities in the country. Whatever happened to the young generation bashing he began with, I asked teasingly. “Well, we are unhappy at the way things are, but I love my granddaughter too much to let my obsessions with religion affect her,” he said

Newspapers have reported that women in the Parsi community have been under pressure to bear more children so as to increase their numbers. Some Parsi organisations have also announced SOPs (standard operating procedures) such as subsidising visits to fertility doctors and providing for larger homes to accommodate bigger families.

But the community is one of the richest and highly educated in India. Therefore, women in the community tend to marry while in their early or mid-thirties, after the passing of some crucial fertile years. Also, most Parsi women are professionals, making it very tough for them to have many children.

Dajee has four sons. His wife used to teach at a local school in Dadar before she retired. “It was easier back then,” he said. “Neither of us worked too much,” he laughs. He was an employee at the state excise department and retired 14 years ago.

Since then, he walks around in the tiny park at dusk every day. I found my daughter-in-law in this park, he proclaims happily. Dajee was walking one evening when he bumped into his old-time friend who had come down from Gujarat. A few months later, Dajee’s oldest son married his friend’s daughter.

It is only Dajee’s oldest son who has married a Parsi woman. The others have married out of the community. But, Dajee insists that it is not why his oldest daughter-in-law has been his favourite. “She is simply a nice woman, the daughter I never had.” he said.

It is almost 7pm and Dajee gets up to leave. “We have dinner together every night,” he says. It is the only ritual he doesn’t miss. It is the only ritual that has been the same for all of his adult life. It is the only ritual he would fight to keep intact.

Flyways of fortune

While the upper crust stayed in Pakistan, the professionals and working class mostly opted for greener pastures abroad

By Teenaz Javat

The Zoroastrian diaspora as we know it today is spread across the globe. As a mercantile community the Parsis have been traders and no place was considered too far or too dangerous to venture, if it meant we could trade with the other.

|

| All about the kids: a traditional Parsi birthday ceremony / Photo by White Star. |

Towards the middle part of the 19th century Parsis had established links to the far-flung corners of the British Empire, Burma and as far east as Shanghai in China. By the time we gained independence from the British, the Parsis of Pakistan were a well-established community, having contributed toward the growth of the country far more than any other minority community pre-partition. For that reason and more, Parsis were often looked upon, and admired as beacons of success and respected city builders.

However, something changed in the mid-1950s and Parsis started moving out of Pakistan and emigrating to the West. Yazdi Kabraji was one such pioneer and among the first Karachi Parsis to come to Canada. According to his niece, Nilufer Mama, who came to Canada in 1972 to join her husband Danny, “Yazdi uncle had no compelling reason to leave a well-established life in Karachi, except that he wanted to live the Western lifestyle,” she says.

What started as a trickle in the mid-1950s turned into a flood by the time the 1971 war started.

It was then that a young Pakistani-Parsi chartered accountant by the name of Sam Vesuna decided that enough was enough and wanted out of the country.

“The loss of East Pakistan, the nationalisation of many industries by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and the threat (which did not materialise) to nationalise private schools spurred me to leave.”

Vesuna came to Canada in the winter of 1972. The tragic loss of East Pakistan and the conditions he witnessed during his business trips to Dacca, coupled with rampant bureaucratic corruption, was cause for concern. “As political conditions deteriorated, so did the economic environment. That’s when I realised that I didn’t want to bring up my three sons in this scenario, so we left,” he adds.

Vesuna, the son of a Parsi doctor, initially had a lot of hope for Pakistan. “After completing my studies I returned to Pakistan in 1961 to contribute my knowledge and skills. Pakistan was a developing country with great potential. In the late 1950’s and early 60s, the World Bank and IMF had cited Pakistan as an example of solid development and the best return for every dollar invested in loans and grants. Sadly, I left in December 1972 with my family, completely disappointed and frustrated.”

|

The first Parsis to move out of Pakistan were the professional class. They had no businesses or property of great value to leave behind. These professionals felt confident that their skills will be recognised and accepted in the new country. They were prepared to accept the early sacrifices of loss of job status, extreme cold and other hardships new immigrants face, for the reward of a safe, uncorrupt and secular environment.

Jang Engineer was one of them. As a 20-year-old commerce graduate, he was part of a group of almost 15 young Parsi men who left Pakistan, a majority of them for England. “I had many friends in the UK working to become chartered accountants. And we used to hear stories of rampant racism in England. I decided to try another country and zeroed in on Canada.”

The trigger to leave happened at a job interview at a British bank in Karachi, when the white man interviewing Engineer told him that while he found his qualification matched the job profile he had applied for, the bank needed to hire someone from the ‘political class’ for obvious reasons. “That did it for me,” says a not-so-bitter-now Engineer. “I said better to leave now than later.”

He came to Canada in 1970 and while he’s returned several times to visit a large extended family, he has no regrets. A recent grandfather, the Engineers have thrived in Canada and never looked back.

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, family class immigration allowed many young men to sponsor their wives, parents and siblings, thereby eliminating to a large extent the anxiety and loneliness that a new immigrant faces when going to a new country. Soon, the numbers were such that by the mid-80s, the Parsis had established places of worship in Toronto and Vancouver.

In the mid-1990s the lesser skilled among the Parsis decided to leave Pakistan. These immigrants to Canada faced greater initial hardships, but were prepared to make the sacrifice for their children.

That said, the well established, wealthy business and landlord class were not inclined to take chances and leave Pakistan as they had a very comfortable lifestyle, a lot to lose materially and socially, and could afford to live with corruption and still get what they needed.

“The moneyed Parsis stayed behind,” says ZavareTengra who came to Canada in 1996.

“Life in the beginning was tough; the long cold winters, the lack of social status and above all the downgrading in workplace, were challenges I knew I would face and have to cope with when I came here.”

Tengra who owned and operated a small family business was deeply involved in the socio-cultural scene in Karachi. Once in Toronto, he was prepared to take up any job to make do in the early days. “I missed my domestic help a lot. But then, that was expected and I was prepared for it even before I came here.”

While Tengra’s immigration process took less than a year, settling in took longer. He soon realised that coming to Canada was the easy part. “I really can’t think of a reason why I left except to experience a differing lifestyle. I wasn’t a professional back home so was willing to take on any challenge.”

Nineteen years later, Tengra has no regrets. A well-known figure on the Toronto arts and social scene, he is the face of Pakistani Parsis in Canada.

Through participation in interfaith activities, the Parsis are slowly being recognised both as a faith group and a religious community. Vesuna has been a long standing president of the Zoroastrian Society on Ontario. He also sits on the board of the Ontario Multi-faith Council and Toronto Area Interfaith Council. As well, the Parsis have been represented as Zoroastrians in the annual opening services of the Courts of Ontario.

Ron Kharas an early immigrant to Canada succinctly puts it, “The Parsis who came to Canada have been trained to work at a job and few have businesses to write home about. It’s the professionals and working class that came here. While we haven’t reached the social standing we had in Pakistan, Parsis have been in Canada just over 50 years, and for that I think we’ve done well for ourselves.”

Like sugar in milk

They built educational institutions, hospitals, contributed to local architecture and even after achieving personal feats, remained modest and down to earth

By Shazia Hasan

Legend has it that when the Parsis first arrived in the Subcontinent, the raja of Sanjan, who didn’t speak the same language as them, presented their elders with a glass of milk that was filled to the brim. He was trying to indicate that there was no room for them in the land, which the wise people understood immediately. They responded by adding a spoonful of sugar to the glass. Without saying a word, they told the raja that they would blend into the locality while sweetening it with their presence.

And that’s what they did: they integrated into the society giving it back what they could. Here we recall a few prominent Parsi citizens of Pakistan.

Jehangir Kothari

The gentleman after whom the Jehangir Kothari Parade in Karachi is named was a great philanthropist and well-travelled man, who among other things was a member of the Karachi Chamber of Commerce, an honorary special magistrate in Karachi, member of the cantonment and municipal committees in Karachi, a lieutenant in the Sindh Volunteer Rifle Corps and a patron, trustee or president of many charitable and other institutions in Karachi. He built the pavilion, parade and pier after demolishing his own house in 1907, to give the people of Karachi a recreation spot.

Jamshed Nusserwanji

Also known as the ‘Builder of Modern Karachi, he was the first elected mayor of the city who had previously also worked for the Karachi Municipality as a councillor and president. He built roads lined with shady trees and parks, hospitals, schools, libraries, a transport system with well-planned sanitation and water systems.

Seth Shapurji Hormusji Soparivala, Seth Edulji Dinshaw and Ardeshir Hormusji Mama

Both the Bai Virbaiji Soparivala (BVS) Parsi High School and the Mama Parsi School are offshoots of the grand tree planted by Seth Shapurji Hormusji Soparivala and his family in 1859. BVS Parsi High School was then a small Parsi Balakshala housed in the residence of Dadabhoy Palonji Paymaster. But as the school-going community grew, it had to move to a bigger place.

In 1869, Seth Shapurji, the school’s biggest benefactor, donated Rs10,000 to the school with the request that it be named after his late wife Bai Virbaiji. The new school building at Abdullah Haroon Road was completed in 1905. Instead of remaining exclusive to Parsi children, BVS School opened its doors to children of all faiths in 1947 on the request of Quaid-i-Azam.

The Mama Parsi School for girls was established in a portion of the BVS School in 1918. In 1919, it was shifted to another building on the same road known as the Mama Mansion. The school in its curent campus started lessons in April 1925 and opened its doors to girls of other faiths in 1947.

Justice Dorab Patel

He was a Supreme Court judge who refused to take an oath of allegiance to Ziaul Haq in 1981. Had he done so, Justice Dorab Patel would surely have become the chief justice of the SC. A campaigner for human rights throughout his life, he later devoted himself to such causes; besides being the founding member of the Asian Human Rights Commission, he was also the co-founder of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. In 1990, he became the second Pakistani to be elected a member of the exclusive International Commission of Jurists.

Jamsheed Marker

A speaker of over half a dozen languages, one of Pakistan’s top envoys, Jamsheed Kaikobad Ardeshir Marker is a record-holder in the Guiness Book of World Records for being ambassador to more countries than anyone else. A huge lover of cricket who has also been a radio commentator, he has the distinction of being the first to broadcast live from the National Stadium Karachi.

Ardeshir Cowasjee

Driving around town in his convertible silver Mercedes, Ardeshir Cowasjee was as fearless as they came. Born into a shipping family, Ardeshir too joined the family business but was heartbroken when his shipping company, the East and West Steamship Company, was nationalised by the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1974. Still, he carried on with his philanthropy work. The Cowasjee Foundation has been responsible for providing funding for the higher education of many Pakistani students, while many of Karachi’s major hospitals are among the beneficiaries of the foundation.

Bapsi Sidhwa

Author of The Crow Eaters, Ice Candy Man, Their Language of Love, Jungle Wala Sahib, etc., Bapsi was one of the first English language authors of Pakistan to make a name for herself abroad. She has encouraged many of Pakistan’s younger authors.

Byram and Goshpi Avari

Byram Dinshawji Avari is the winner of two gold medals for yachting in Asian Games: first in the ‘enterprise class’ in the 1978 Asian Games in Bangkok, Thailand with partner Munir Sadiq; then with wife Goshpi at the 1982 Asian Games in New Delhi, India. Byram also has a silver medal from the Enterprise World Championship held in Canada in 1978. Following a career in politics, Byram now serves as the honorary consul for Canada while also concentrating on his hotel business these days.

Goshpi is the president of the Pakistan Scrabble Association. Having attended a scrabble competition at the US Consulate in Karachi, she opened the doors of Beach Luxury Hotel, gratis, to scrabble enthusiasts where since the formation of the association in 1989, professional and amateur scrabble lovers gather to play every weekend.

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, March 22nd , 2015

On a mobile phone? Get the Dawn Mobile App: Apple Store | Google Play