RECENTLY, I had the opportunity to attend a conference in Herat on the cultural and social aspects of security followed by a bilateral meeting on the latest developments in Afghanistan-Pakistan relations. Herat is the only surviving city among the four centres of historical Khorasan. The others were Balkh (the home of Maulana Rumi,) Marv and Nishapur.

Herat is from where the two greatest saints of Islam in the subcontinent came: Hazrat al-Hujveri Data Ganj Baksh to Lahore in the ninth century and Hazrat Gharib Nawaz Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti to Ajmer in the 11th century. Under the Tahiri Sultanate, Herat was the successor of Baghdad as the most brilliant centre of mediaeval Islamic civilisation. Its influence radiated in all directions: to Samarkand and China; to Nishapur and Constantinople (Istanbul;) to Marv and Bokhara; to Mashhad, Kerman, Shiraz and Isfahan; and to Kashmir, Lahore, Ajmer and Delhi.

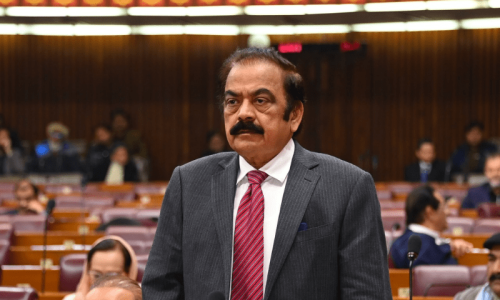

The conference was held in the magnificent 800-year-old Fort of Herat which testified to the city’s past glory. It has been excellently described by Senator Afrasiab Khattak in a recent newspaper article. He is appropriately known as a ‘bridge-builder’ between Afghanistan and Pakistan. His services are needed more than ever in the current fragile phase of the bilateral relationship.

When President Ashraf Ghani chose Pakistan as the first country to visit after his election he was making a very bold statement. He was also taking a very significant risk. But he was determined to break out of the morass in which the bilateral relationship had sunk during the presidency of Hamid Karzai. To be fair to Karzai, he visited Pakistan around 20 times in an effort to develop a relationship of confidence and cooperation between “conjoined twins” as he described Afghanistan and Pakistan.

There are many Afghans who believe the Taliban will have to be included in a ‘transition’ process.

Unfortunately, for a number of complex reasons, including the tunnel vision of politically insensitive and generally uneducated decision-makers, that effort completely failed. As a result, the relationship degenerated into mutual recrimination. Ashraf Ghani was determined to bring the relationship out of this quagmire.

The new Afghan president acknowledged Pakistan’s pre-eminent role in brokering a peace settlement between Kabul and the undefeated Taliban. He was even willing to displease India — a traditional and generous friend of Afghanistan — in order to cultivate political and security cooperation with Pakistan. But he insisted Pakistan had to make a choice. It had to decide who were its friends or ‘assets’ in Afghanistan: the elected government in Kabul or the Taliban and its allies who sought to overthrow it? Pakistan apparently assured Ghani that as the elected leader of the Afghan people he was Pakistan’s obvious choice as strategic partner for peace and development in Afghanistan and the region. Ghani emphasised that if Pakistan did not live up to its undertaking his political position in Afghanistan would be undermined.

It seemed a new era of hope in relations between the two countries was about to dawn. Overnight, Ghani became one of the most popular international leaders in Pakistan. High-level civil and military exchanges followed; joint counterterrorism operations were planned; and a memorandum of understanding on intelligence-sharing was signed between the ISI of Pakistan and the NDS of Afghanistan. This, however, caused outrage in Afghanistan. The ISI is seen as very bad news by most Afghans, Pakhtun and non-Pakhtun. The NDS is seen in Pakistan as a hotbed of “anti-Pakistan” sentiment and whose officers coordinate closely with advisers from India’s RAW. Moreover, both Afghan and Pakistani governments are seen as unable to stand up to hawkish pressures.

Unsurprisingly, Taliban attacks not only continued but began to reach Kabul with politically destabilising consequences. The Afghans insist that without the availability of facilities on Pakistan’s territory the Taliban would be no match for the Afghan National Security Forces. Pakistan argues the Taliban are ‘self-sufficient’ inside Afghanistan as indicated by their targets which are located far from the border with Pakistan. This is because the Taliban allegedly enjoy significant support in Afghanistan. Moreover, Ghani supposedly ‘overestimated’ Pakistan’s influence on the Taliban and, accordingly, blamed Pakistan for every setback in Afghanistan. Finally, if Pakistan cut off all ties with the Taliban how would it be able to persuade them to come to the negotiating table?

The Afghan government rejects Pakistan’s arguments and insists a militarily strengthened and politically recalcitrant Taliban would not enter negotiations with Kabul on acceptable terms. Pakistan, allegedly, was playing its usual double game to counter perceived Indian influence in Afghanistan despite Ghani’s assurances that he would never allow India to use Afghan territory against Pakistan. While Pakistan complained of attacks on targets in Pakistan that were planned in Afghanistan and asked Kabul to ‘do more’ to stop them, it knew Kabul had little control over the border areas with Pakistan

Nevertheless, Pakistan was able to arrange the Murree (or 2+1+2) talks in July which all sides pronounced a good beginning. But the mutual recrimination that followed the revelation of Mullah Omar’s death two years ago prevented a second round of talks. Instead, the Taliban offensive intensified culminating in deadly suicide bombings in Kabul and the temporary fall of Kunduz. An embarrassed Ghani alleged Pakistan was “at war” with Afghanistan and the bilateral relationship was no longer “brotherly.” He refused further Pakistani help in negotiations with the Taliban insisting it first deny its territory to them and their allies. The endorsement of Mullah Akhtar Mansur as Mullah Omar’s successor in Kuchlak, 24 kilometres from Quetta, confirmed Afghan suspicions about the role of Pakistan.

It must be admitted there are many Afghans, especially around Kandahar, who believe the Taliban will have to be included in a ‘transition’ process. The majority, however, believes the Taliban can and must be isolated and weakened before any reconciliation process becomes feasible. They see ‘Pakistani duplicity’ as the major obstacle. Ghani feels betrayed. He had warned Pakistan that if it let him down his political position would become untenable. A comprehensive Afghan policy review to restore mutual trust is, accordingly, an urgent priority.

The writer is a former ambassador to the US, India and China and head of UN missions in Iraq and Sudan.

Published in Dawn, October 17th , 2015

On a mobile phone? Get the Dawn Mobile App: Apple Store | Google Play