Cull of the canines

Rabies kills, dogs don’t … so why kill dogs in the first place?

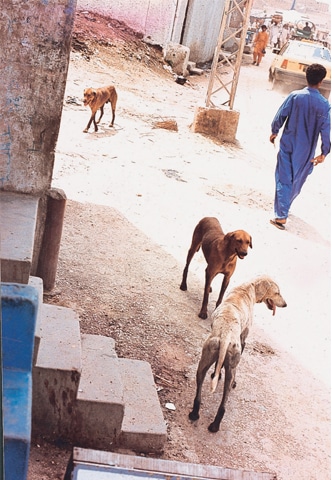

All it takes is 10 minutes for a stray dog to die — poisoned, asphyxiated, twisting, turning and dying a slow and painful death. Municipal administration officials in Karachi believe that poisoning stray dogs is the most effective way of reducing the canine population in the city, but for dog bite victim Zafar Mushtaq, a resident of Karachi’s Garden area, this was a disproportionate response to getting bitten.

“No living being deserves to die this way,” he says. “I was writhing in pain after I got bit, but even I could not bear the sight of the stray dog being chased into a corner and fed poison pellets. How could they have possibly known that this dog was carrying rabies?”

Mushtaq was walking home from the bus stop last month when he was chased by a stray dog and bitten on his calf. Now hobbling around with the support of a crutch, he rushed to a hospital nearby and was administered precautionary injections for rabies. “Each injection cost Rs1,200, and I have been to the hospital thrice now go these injections administered,” he says.

“Poison pellets tend to explode inside a dog’s stomach when they are consumed,” explains a senior officer of the District Municipal Corporation (DMC)-East, speaking on condition of anonymity. “Town administrations tend to conduct this activity once every week.”

The killing of stray dogs in Karachi seems to have resumed as a city-wide activity, prompted by news of “successful operation” against stray dogs inside the University of Karachi (KU). Inspired by the coverage it received — both positive and negative — other town administrations have also followed suit.

Not all dogs need to be killed but it is easier to get rid of them all at once. We don’t have the capacity or the personnel to identify which dog is dangerous and which isn’t. It’s an issue of capacity at the moment; without capacity, how can you expect the government to have the will to save animals?

“It costs between Rs170,000 and Rs180,000 for a kilo of poison pellets, which is imported from France. Towns don’t necessarily get the entire kilo; sometimes, our quota might be half a kilo. Not all of it is used all at once, because it takes us two to three months to procure them,” says the DMC-East official.

Every district municipal administration is tasked with procuring the poison and then distributing them onwards to various town administrations. With the poison pellets in hand, town administrations tend to mix them in chunks of meat and drop them in various areas, particularly in and around dumpsters.

“Many years ago, we had a different system. We’d extract a dog with a fork and remove him from one area and take them to a more secluded one — by the banks of Malir Naddi, for example. But times have changed now,” says the officer.

Much of the drive against stray dogs is driven by a fear of rabies, which is almost always fatal if contracted by humans. Humans can only contract rabies if they are bitten by a rabid animal, but once they do and if it goes unvaccinated, it is only a matter of days before the victim dies.

Animal rights groups argue that the only humane way to manage the canine population in the city is to carry out mass vaccination drives in stray animals across the city.

“Even in the KU case, we proposed to the university administration that there is a humane way to control canine populations but they didn’t want to listen,” says veterinary physician Mohammad Ali Ayaz, who owns and runs the Animal Medical Care (AMC).

For Ayaz, there are no short-term fixes to the problem of rabies, or indeed that of stray animals.

“KU did what they had to, but the walls of the university are porous for animals. Any stray dog or cat or other animal can simply walk inside. Will we then have this debate of killing stray animals all over again?” he asks rhetorically.

On World Rabies Day this year, the World Health Organisation (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the Global Alliance for Rabies Control (GARC) called on governments across the world to invest in cost-effective mass vaccination programmes of dogs.

For Ayaz, this is the way forward.

“The only way to think about this issue is long-term: what you need to do is to catch stray dogs, vaccinate them, and if possible, neuter them,” he says. “This way, incidence of disease is controlled and so is the population of stray animals. Over a longer time frame, you’ll see the population of stray dogs to reduce dramatically.”

This perspective is lent weight by a former senior town official, who was in office during the tenure of the last democratically-elected city administration.

“We tend to adopt a one-size-fits-all mentality,” he says. “Not all dogs need to be killed but it is easier to get rid of them all at once. We don’t have the capacity or the personnel to identify which dog is dangerous and which isn’t.”

In an ideal scenario, says the former officer, town administrations would have teams of veterinary physicians operating alongside town staff. But in practice, the culling of stray animals is an inconvenience for municipal administrations as it adds a layer of responsibility that they’d much rather avoid.

“Our municipal administrations don’t have enough personnel to do human-related jobs, let alone those of animals. It often takes months just to pick up garbage or construction debris, because of a shortage of staff. It’s an issue of capacity at the moment; without capacity, how can you expect the government to have the will to save animals?” argues the former official.

“If you talk about humane ways of killing animals, we always issue a notification through newspapers to inform residents that culling will take place on so and so date and in such and such areas, and therefore, to keep their pet animals inside their homes and not let them wander about,” says the officer.

“But sometimes, there is very little time to react if a rabid dog has held a neighbourhood hostage. We aren’t against dogs, but in such situations, we need to react and protect human life,” says the DMC-East official.

What happens to the dogs that are killed?

“Their hides are used in making shoes,” claims the DMC-East official. “There was a Korean contractor some time ago who was given the contract of killing stray animals. But since it wasn’t breeding season yet and he was in a hurry to collect dog hides, he cancelled his contract.”

The writer tweets @ASYusuf

Barking up the wrong tree

As developing countries are confronted with poverty, illiteracy, sanitation, disease, women’s empowerment and now even terrorism, animal welfare does not figure anywhere. Stray dogs could be deemed a public health issue and perhaps more humane methods could be used to control the population of street dogs. Here is what is being done in other countries to cull stray dogs:

Bangladesh: Beaten to death

Dogs were beaten to death with sticks in the streets.

Philippines: Carbon Monoxide euthanasia

Car exhaust is piped into a metal box which causes a slow and painful (20-30 minutes) of carbon monoxide euthanasia.

Bhutan: Shot dead

Cold and simple. Dogs are shot dead.

Mauritius: Chemical poisoning

Dogs are killed using extremely painful, lethal chemicals.

India: Electrocution

Dogs are made to stand in a room knee deep in water in which electric current is introduced.

All these methods have proved to be ineffectiveas neither rabies nor dog populations have gone down. Dogs have a unique ecology; the only way that their populations can be reduced is by ensuring a healthy population of sterilised and vaccinated dogs, who will prevent new dogs from coming into the territory.

Pawfect Samaritans

In a society that is largely dismissive of animal rights and abuse, some souls in Karachi and Lahore offer a lease on life to stray animals

Step in to the Edhi Animal Shelter and a clowder of cats is most likely to greet you. Some clamber with an amputated leg and bruises, but that doesn’t stop any of them from purring around your feet, coaxing you till you pet them. The puppies soon follow; wagging their tail in excitement and finally settling down somewhere near your feet.

Far away from human habitat, this shelter is situated on the outskirts of Karachi, a little ahead of Toll Plaza on the Superhighway connecting the city to Hyderabad. Although barren and deserted, in this sprawling four acres of land, the voiceless, injured and abandoned animals have found a safe haven.

In a country where animal cruelty has taken many forms, from lifting the ban on the hunting of Houbara Bustards to deplorable conditions in zoos and brutal killing of pet animals with bullets, the existence of an animal shelter gives a tiny glimmer of hope in a largely hostile environment.

Not many of the animals here are pure bred; they are indeed stray, picked up from across the city in a severely injured state and battling for their lives. But after treatment, care and much taming, they have proven to be no less lovable than pure breeds.

While some animals sustain natural injuries, there are also those that are subjected to abuse and cruelty at the hands of humans.

“We usually get injured animals with bullet wounds around celebratory days because of aerial firing. But this one time we found a dog who had been shot six times,” says Ayesha Chundrigar, founder of the non-governmental organisation Ayesha Chundrigar Foundation (ACF) that has been actively handling the Edhi animal shelter since March 2013.

“He was deliberately shot and we don’t know who did it. It was a miracle that he survived because the bullets didn’t penetrate his organs. He is now healthy and alive,” says Ayesha.

ACF has a single ambulance that patrols around the city from 10am to 6pm with a vet and responds to distress calls that report an injured animal; they are then brought to the shelter for treatment.

We usually get injured animals with bullet wounds around celebratory days because of aerial firing. But this one time we found a dog who had been shot six times.

With limited resources and almost no assistance from the government, this sanctuary does it best to rescue injured stray animals from the city, including donkeys, horses and birds. But they are very stern about not taking in any pets.

“People get bored of their pets and want to abandon them but we strictly don’t take pets in. They at times call us for veterinary help for their pets but we only want to focus on stray animals that don’t have any owners to look after them,” says Dr Ghulam Fareed, sitting in a shed surrounded by cats lounging about, most of them take an afternoon nap while some kittens play under the cool shade.

On the far end are a few cages lined up against the wall with animals in a seemingly deep sleep, this is where the severely injured cats or dogs are kept for recuperation.

“We do need a surgical room and a more hygienic setup. We are planning to have one in a shelter that is under construction for now,” says Dr Fareed.

Religious restrictions and a nil response to adoption

Separated from this shed is a locked door that paves the way for a ground that stretches far into the open. Here, there is harmony as the animals play together in kennels and a visitor is welcomed instantly with friendly jumps and wagging tails.

Seeing them tamed and healthy, it comes as a surprise that not many are willing to adopt these friendly animals.

“We have tried posting their pictures in the past in the hope that someone will come to their aid but the response has been nil, people always want pure breeds,” says the doctor with dismay.

“We have pure Persian cats too but even then people don’t want to adopt from a shelter. At times people come in to check up on us to see if the injured animal they had reported over the phone was looked after properly, but they never adopt.”

With the fear of dog bites, rabies and citing ‘religious concerns’, the response towards adopting or helping dogs is even more disappointing.

“Both of our caretakers, Mehru and Manji are Hindus and they don’t mind taking care of the dogs,” says Dr Fareed.

Dog bites and why do they occur

In a society that terms dogs as ‘unhygienic’ and ‘dangerous’, and regularly subjects them to violence which includes kicking and hurling rocks and sticks, it is then most likely that the animals perceive every onlooker as dangerous.

“Stray dogs on the road do not know what love or petting is. They are so used to being treated with cruelty.”

The Sindh government culled a significant number of dogs earlier this year when reports of dog bite escalated and steps were needed to be taken to control their population.

“The government thinks culling them is the solution but that will not stop their population, they need to be vaccinated and neutered and that’s the only thing that will help,” says Dr Fareed.

The cost of medicines, treatment, and food is all handled by ACF but the environment they work in is less than pleasant; there is no electricity and no water.

“We have solar panels which we use to run the motor for underground boring water but that is salty and animals dip in it to cool themselves. For drinking water, we get a tanker once in about 10 days,” says Mehru, one of the workers responsible for cleaning and feeding the animals.

A do-it-yourself rescue

A low cry emerged from a nearby dumpster, it was a painful moan. The cries got louder as the flames blazed and smoke from the burning garbage thickened. Passing by the place was 24-year-old Aijaz Hussain who heard the soft cries and immediately went to investigate.

What he saw changed his life forever; six kittens were dumped in the garbage, most of them burned and whimpering in pain.

“Four of them died because of deep burns and only two survived out of which one is still with me. It’s been six years since the incident and since then I have made it a point to rescue injured cats whenever I see them,” says Aijaz, now 30 and a teacher by profession.

There has been a time when Aijaz had 19 cats in his house, waiting to be adopted. He would wait for the animal to heal and overcome the trauma fully before uploading its pictures on Facebook for people who would be interested in adoption.

“I once found a cat which had maggots in the chest and it took three weeks to heal. She was very aggressive because of the illness but I tamed her over time and now she has been adopted and the owner is very happy too.”

With the government’s slow response to safeguarding both human and animal rights and a ‘constitutional silence’ over protection of animals, concerned citizens have taken matters in their own hands.

Much like Aijaz, there are other independent rescuers who have been actively saving animals from the streets of Karachi and taking care of their health and nurturing on their own.

The team suffered another blow at their next shelter in Chungi Amar Sadhu area of Lahore where the rescued animals were beaten as were the members. “The land we had rented out was in dispute between two brothers, we were not aware of this and were told by the landlord to evacuate.

But the limitation they face is similar: shortage of space.

“I have to lecture my friends regarding adopting a stray. There are some very good individuals who would open their doors to any animal but the majority switch off as soon as you tell them the animal is from the street,” says Aijaz.

But even those who can’t adopt due to space issues, there are some small acts that would go a long way in making a significant difference.

“I keep clay pots in my car and some water at all times. Whenever I see a donkey on the road in the hot weather, I keep the water in front of them. This is something that everyone can do.”

From Facebook to a shelter house

When two 22-year-olds in Lahore took upon the task of rescuing animals around the city, never had they imagined they would end up having a shelter for their cause.

Sehrish Neno and Mubeen Shahid from Lahore had been happily making a number of rescues in the city on a short scale, taking in injured dogs and cats and finding them homes through Facebook. But a single incident made them lose all hope from the system, forcing them to take complete charge of their rescue missions alone.

The young duo had found a stray dog run over by a car, bleeding and in pain with a broken leg. He was rushed to a clinic in a dire state where he underwent surgery, the rescuers visited him every other day to check his progress, hoping against hope for his survival.

But they went back after a two-day break, only to find a horrible sight in front of them.

“His bandage had not been changed, that dog hadn’t been let out at all. He was lying on his own filth because of which his congestion worsened and he had to be put down. If only the clinic had taken post-surgery care, he could have lived,” says Kiran Maheen, who is now managing the shelter as well.

This is when the two youngsters pledged to take all their rescued animals under their own care. Today, they function under the name ‘Society for Protection of Neglected Animals (SPNA)’ with a five member team that looks after stray and injured dogs in a shelter on Multan Road which has approximately 20 kennels.

Similar to ACF in Karachi but working on a smaller scale, SPNA rescues dogs across Lahore that are reported to them through Facebook page, groups such as Pet Talk or word-of-mouth. But just like other animal saviours, the young team of university student battles with negative perceptions about keeping and caring for dogs.

“There is a perception that dogs are impure and they would bite. I have handled stray dogs for years and I have yet to be bitten. Dogs don’t bite until they have rabies and not all stray dogs have it,” says Kiran.

The negative mindset towards animals, particularly dogs, has not been the only problem, finding a stable shelter has been an irksome task for the young rescuers.

“We have had to shift our animals twice from different areas because of the hostility inflicted upon them by neighbours,” says Kiran.

The team was forced into leaving their very first shelter in Makkah colony near Gulberg when a woman in the neighbourhood left phenyl tablets near the animals, resulting in the death of two puppies.

“She said they were impure and was downright annoyed by their presence, although the animals never directly affected her. When we confronted her, she said she would continue if we didn’t shift.”

“The puppies had been adopted and were ready to leave the very next day,” says Kiran remorsefully.

The team suffered another blow at their next shelter in Chungi Amar Sadhu area of Lahore where the rescued animals were beaten as were the members. “The land we had rented out was in dispute between two brothers,

we were not aware of this and were told by the landlord to evacuate. We asked for a week’s time to find an alternate place to which he agreed, but the very next day we found the shelter locked.”

Worried about the safety of the animals, some members tried to move past the door to feed the animals only to be beaten up by the landlord and neighbours. “Even the police intervened and arrested one of our team members and caretaker on false charges of trespassing, all this time the rest of us were not told if the rescued animals were safe inside.”

Early morning the next day, the team found out much to their dismay that the shelter gate where the animals had been kept was left open, and only three of the 16 rescued dogs were found inside.

“For a week after that incident we searched for our dogs but only managed to find four. We asked everyone in the neighbourhood but no one helped, we even put up a Rs2,000 cash reward for finding them but it was all in vain. The most devastating part is, four of those dogs were paralysed, they cannot even run or protect themselves.”

Forced to drink acid

Being an animal enthusiast since her childhood and her years of rescuing stray dogs, Kiran has seen all kinds of atrocities subjected to stray dogs. They have been beaten up for no reason, poisoned by phenyl tablets, abandoned by their owners out of boredom, but amongst all of these harrowing experiences, one incident has left an ever lasting impact on her.

“I got a call one day from a girl who reported that there was a dog outside her house on the street who was screaming in pain, she thought he was beaten up and his legs were broken.

“We went there and found that he was in immense pain and found that something was coming out of his mouth and we weren’t sure what it was. We rushed him to the clinic where the doctor said someone had poured acid in his mouth, his mouth had disfigured and by midnight we found that his organs were slowly melting away.”

Devastated and horrified, they waited for six hours to see if there was any progress, praying for a miracle to save him but there was nothing that could be done.

“He had to be put down. That dog used to live on the street and the people in the area used to take care of him, no one had any idea who put the acid in his mouth.”

‘Not my responsibility’

In the midst of the barbarity and heartlessness, there is an existing minority that reports, donates and is interested in doing their part to save the dying animals. But their numbers are very few.

“There was a case in Gujranwala where someone had broken the legs of a dog. We got a message on Facebook for help and almost immediately, a member volunteered to give his car so that we could go and rescue the dog all the way from Gujranwala,” says Kiran. “He was saved in time and we named him Burrito.”

Such cases though are rare, and apart from few positive responses and a handful of dedicated helpers, the team still receives a dearth of cases everyday where people simply call up SPNA to take their pets away giving reasons like shifting houses, or simply stating that the animal ‘is no longer my responsibility’.

“Animals have feelings too and when they are given up, they feel the rejection and trauma. The rescued dogs feel the most, and they are more responsive than pet ones, they would do anything for a little bit of love.”

SPNA survives through the monetary help that they receive for most of the surgeries, even for food for the animals in the shelter.

Having shifted two shelter homes so far, the group of youngsters now struggle to continue their mission on few donations, limited resources and an altogether discouraging response from society.

“We have decided to put a stop to our rescues for the time being because we just don’t have enough funds and people are not ready to adopt stray dogs. We are still going and treating injured animals but there is no room for us to take in any more. Finding another shelter too is a gruelling task,” says Kiran gravely.

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, November 22nd, 2015