Gendered nutrition

by Hilda Saeed

In many households across Pakistan, women and girls often get smaller food portions ... but at what cost?

A crisis has been hiding in plain sight for many decades: Pakistani women suffer immense micro-nutrient deficiencies, which in turn, are adversely affecting their visibility and contribution to society. This goes beyond traditional notions of healthy mothers; it is equally about healthy working women, whose nourishment is critical to any national development project.

Medical studies have been pointing to this alarming situation for long: a study carried out in 2000 reports that the health of the population is adversely affected by inequities, with women and children worst affected. More than half our children lack the all important protein energy component. Such a magnitude of malnutrition points to stark inequities within the country.

When it comes to statistics, there isn’t much in the way of up-to-date numbers and analyses. The last official survey, National Nutrition Survey (NNS), was conducted in 2011. Its findings were released in 2013, and as expected, the situation had taken a turn for the worse.

As per the NNS-2011, 51 per cent pregnant women were anaemic, 46pc suffered from vitamin A deficiency, 47.6pc from zinc deficiency and 68.9pc from vitamin D deficiency. Malnutrition was only slightly lower among non-pregnant women — 50.4pc of whom were anaemic, 41.3pc had vitamin A deficiency, and 66.8pc had vitamin D deficiency. A remarkable 58.1pc of households are food insecure and only 3pc of children receive a diet that meets the minimum standards of dietary diversity.

Where does this leave Pakistan in global standings for gender empowerment? Lodged at the bottom, ranked 144 out of 145 countries.

This begs the question: are Pakistani women deliberately being deprived of food?

The NNS-2011 found that nutrient deficiencies affected over 35-39pc of adolescent married women, while the problems only increased with age. Major reasons for high maternal mortality are malnutrition, severe anaemia, poor access to prenatal care (28pc) and dearth of trained attendants at birth (20pc).

As per the NNS-2011, 51 per cent pregnant women were anaemic, 46pc suffered from vitamin A deficiency, 47.6pc from zinc deficiency and 68.9pc from vitamin D deficiency. Malnutrition was only slightly lower among non-pregnant women — 50.4pc of whom were anaemic, 41.3pc had vitamin A deficiency, and 66.8pc had vitamin D deficiency.

Gender discrimination, gender roles, and social norms affect women more: they can lead to early marriage and childbearing, close birth spacing, and under-nutrition, all of which contribute to malnourished mothers.

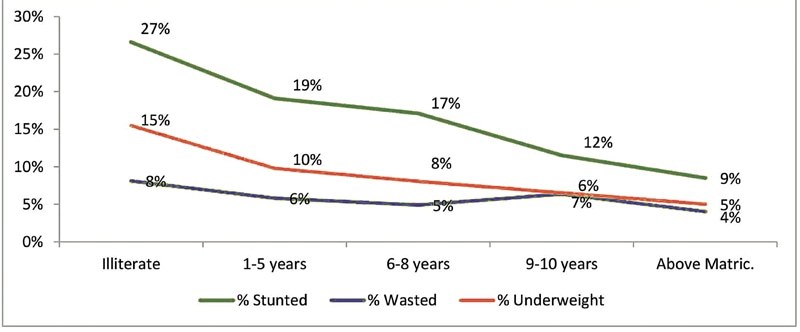

This in turn affects children: even though the proportion of underweight children has declined during the last one-and-a-half decades, approximately one-third of young children are still underweight. Stunting and wasting have actually increased: among children under the age of five years, stunting has increased from 41.6pc in 2001 to 43.7pc in 2011, and wasting has increased from 14.3pc in 2001 to 15.1pc in 2011. There has been no change in the percentage of underweight children since 2001, which is 31.5pc.

“If you notice, people do not allow housemaids to bring their babies along. As a result, their children are often not well fed,” argues Dr Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, the founding director of the Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health at Karachi’s Aga Khan University (AKU).

“Unfortunately, society does not encourage breastfeeding, and daycare centres for working women’s children are absent,” he adds, while emphasising the need to encourage breastfeeding, as this decreases the risk of death in the first two years of a child’s life.

While it is convenient to assume that malnutrition is merely a problem borne of poverty, it is in fact a problem that cuts through class and income backgrounds, and is not restricted to women of a certain class. Poor income is not the only predictor of malnutrition; gender, urban-rural differences in access, utilisation and quality of healthcare also influence health. Then there are underlying factors such as illiteracy, unawareness of the mother about healthy behaviour, lack of decision-making power of women, and deep-rooted cultural values of a patriarchal system that hinder women’s nourishment.

It is a ‘culturally’ accepted norm, particularly among the unlettered, that women can survive easily on minimal food without encountering any ill effects. Gender biases exist within households in patterns of food allocation, with women often receiving a lower share of food requirements than men. Even expectant mothers are given no additional food portions.

Traditions and superstition are plentiful too: for instance, it is believed that adolescent girls shouldn’t eat ‘hot’ foods, i.e. foods that are nutritious and energy giving, such as eggs, meat or fish.

Because of such customs, not only are their lives endangered but the continued malnutrition may lead to further dire consequences: it weakens women’s ability to survive childbirth, makes them more susceptible to infections, and leaves them with fewer reserves to recover from illness.

Marriage and childbirth brings greater predisposition to illness and even death; further, the babies born to them are at higher risk of malnutrition. Adolescents and young married women become even more affected, because their access to services is curtailed by their low decision-making power in the household, limited mobility, and strict veiling norms.

The well-being of a population is based on prevailing economic factors, particularly income and consumption patterns; however, it doesn’t depend solely on these; social indicators such as life expectancy, health, education and nutrition are also important dimensions. Given the nutrition status quo, it is no surprise that Pakistan has the highest maternal mortality in the South Asian region, and among the world’s worst maternal mortality ratios, and prominent nutrition-deficiency diseases.

Financial crises and scarcity of food are described by the NNS survey as the prime culprits. But an assessment of the proportion of boys and girls (ages 13-18) consuming below 70pc of recommended nutrients indicated many gender discrepancies, including in consumption of high-protein foods such as meat, fish and eggs. This may be because boys are given preference within the family in the consumption of more costly high-protein foods, while girls rely more on high-calorie staple foods, and remain undernourished.

The status quo points to Pakistan’s failure to address malnutrition among women despite the Constitution emphasising the right to food in Article 38: “The State shall provide basic necessities of life, such as food, clothing, housing, education and medical relief.”

Pakistan has keenly signed and even ratified various covenants, treaties and conference recommendations. The human right to adequate food has been recognised in different international instruments, most notably the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR); the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW); and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

It’s a depressing picture, but to look ahead at future promise — Pakistan’s adolescent promise — it’s critically important to safeguard and improve their nutrition, step up their calorie intake, and to enable them to become healthy, productive members of society.

To begin with, successive governments need to do away with their short-sighted and reliance on donor agencies to fill the nutrition gap. There needs to be adequate allocation of funds from the national exchequer for human resource development, with well-planned policies and programmes, and targeted, time-bound solutions.

It is equally important for Pakistan’s new nationalist project to ensure gender justice and gender equality by removing discriminatory laws, customs, policy decisions that relegate women to subservience. Malnutrition in women leads to economic losses for families, communities, and countries; it reduces women’s ability to work and can create ripple effects that stretch through generations.

Adolescent girls are especially vulnerable to malnutrition because they are growing faster than at any time after their first year of life. They need protein, iron, and other micronutrients to sustain the adolescent growth spurt and meet the body’s increased demand for iron during menstruation. But usually they suffer from iron deficiency anaemia, and protein energy malnutrition, iodine deficiency; they have low serum calcium, vitamin D and vitamin A levels.

It makes sense therefore to further step-up girls’ and women’s nutrition, health and education — much more than the steps being currently undertaken. Fortification of staples with iron, iodine, vitamin A, and other micronutrients; fortifying sugar with vitamin A and salt with iodine and wheat flour with iron are all relatively simple steps to take forward. Adolescent girls and pregnant women are especially in need of iron and folic acid supplementation. Cheaper sources of high biological value protein, legumes and soya beans are also good alternatives for the purpose.

Malnutrition can be addressed by long-term initiatives including food security, child protection, empowerment of women, targeted agriculture safety nets and early childhood development programmes. Improving female education, enabling women to become economically self-sufficient, and motivating them to utilise health facilities, emphasis on balanced diets for mothers, sensitising caregivers and health personnel to gender issues will help enhance their health status.

The writer is a development worker and women’s rights activist

Early marriages and nutritional deprivation

by Zofeen T. Ebrahim and Madiha Latif

Marrying girls off robs them of more than just their innocence

To best understand malnutrition in women, one has to look at the issue more holistically, as malnutrition does not just suddenly occur in women. The “nutrition deprivation” in the life cycle of women, where they are in a constant state of nutritional stress from childhood to adolescence to childbearing period, is the central issue.

Public health expert Dr Inayat Thaver explains the “inter-generational cycle” thus: “A female baby of low birth weight (LBW) is born, fed inadequately; reaches puberty, is married off early, delivers a number of babies who may also be of LBW.”

Malnutrition plays a key role in maternal mortality, just as in infant and child deaths. “A pregnant mother’s nutritional status is linked to what she was as a child, a young girl and then an adolescent,” argues Dr Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, the founding director of the Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health at Karachi’s Aga Khan University, while emphasising on the need to end teenage motherhood.

Arshad Mahmood, advisor to SUN-Civil Society Alliance, Pakistan, a coalition of over 100 organisations working for the rights of food and good nutrition of the people, contends that the link between maternal under-nutrition to child under-nutrition has already been proven.

“It is evident from the fact that the 1,000 days plus approach has strongly been recommended focusing on pre-conception, conception, pregnancy and lactating women,” he says.

“The growth of the unborn baby which is drawing all the nutrients from the mother and the physiological changes the young woman is going through, increases the need for iron. If she’s already deficient in micronutrients, she will be more susceptible to anaemia and its consequences,” agrees Bhutta.

Further, multiple pregnancies is another cause of anaemia and reduces a woman’s ability to survive bleeding during and after childbirth.

Unfortunately, malnutrition may not always be visible unless the woman is taken to a doctor. But the signs to look out for, according to Thaver, are fatigue or “undue tiredness”.

In addition, says Bhutta, if a woman is short of breath, complains of dizzy spells, or suffers from loss of appetite, it can point to anaemia.

“This, in turn, is mainly due to iron deficiency which can also be attributed to other factors, such as chronic infections, but a major reason is lack of nutrition,” he insists.

In 2014, in a significant move, the Sindh Assembly passed a bill prohibiting the marriage of children under the age of 18. According to Unicef’s State of the World Children report in 2013, about 21pc of marriages included children under the age of 18.

Early marriages of girls are common practice in Pakistan, despite widespread condemnation. This custom is primarily driven due to poverty, and gender discrimination. Girls are viewed as an economic burden on families, and thus early marriage is a form of relief. Many girls are married off to settle disputes. These marriages are forced, or arranged, causing serious damage to the emotional, mental, physical and psychological health of a girl child.

When married early, they tend to become pregnant at an early age. According to Plan UK, “complications in pregnancy and childbirth are the leading killer of young girls in developing countries”.

Dr Shaista Effendi, a doctor at the Ziauddin University, has worked on many cases regarding underage pregnancy and childbirth. She explains that vital organs may get torn during the process of giving birth, and with repeated birth, sexual intercourse and even abuse, the repair of these organs is difficult and long drawn, making them susceptible to infections.

According to Kausar Saeed Khan, associate professor, department of community health science, Aga Khan University, appropriation of healthcare resources are focused on those better off in Pakistan; she says there are no special resources allocated for underage mothers, and the resources available are inadequate.

Both Kausar and Dr Effendi affirm that underage brides are susceptible to physical and sexual violence, and lead subservient lives. They are denied the right to education and freedom, which stunts their personal development and self-growth. The psychological trauma of marrying at a young age puts them at risk of depression and there is also an increased risk of psychological / psychiatric disorders.

Dr Effendi is of the opinion that the change in home environment, emotional stress of leaving the loved ones behind, and the pressure of being “wives” and “mothers” cause a lot of stress-related issues. Kausar articulates that they are suppressed, forced into roles that they are not ready for, are unable to express themselves and have to cope with unimaginable pressures.

Since they are young and often malnourished, with added pressures of child rearing they never gain health and always remain malnourished; children born to them are also malnourished and as the mother hardly has any knowledge about nutrition and health, the children fail to gain much health.

Education on the impact on health of early marriages is of utmost importance. Early marriage is a gross violation of a child’s rights, which needs to be fundamentally and firmly protected and preserved.

Zofeen T. Ebrahim is a freelance journalist and tweets @Zofeen28

Madeeha Latif has a special interest in social issues.

She tweets @madiha_latif

Smart economics

by Moniza Inam

More control over household finances for women translates into better nutrition for the family

Two years ago, tragedy had become a permanent resident of Amna’s house. At just 25 years of age, Amna is already a widow and mother to two. She lost her husband first, in a terrorist attack, back in 2014. She was then forcibly evicted from her in-laws’ residence along with her children. And although they found shelter with Amna’s parents living in a slum in Karachi, the young family had been pushed into food insecurity.

Without any education and skills, Amna no longer has a viable source of income to afford a decent standard of living and education. Her children now suffer from malnourishment; their growth has been stunted due to a low calorie intake and poor diet.

Many miles away, 35-year-old Mumtaz Bibi, who lives in a village near Multan where she works as a farm worker, can empathise with Amna’s helplessness. Like most women of her community, Mumtaz was married off at a very young age and bore 11 children.

She looks significantly older than her age and suffers from acute iron deficiency, asthma and low blood pressure because of repeated pregnancies as well as a lifetime of hard, menial, and at times, unpaid work. Despite her poor health, she still needs to work as an unregistered worker which deprives her of labour rights including paid leave, medical cover, maternity leave, pension and other entitlements.

In both cases, fate is blamed for the many different everyday struggles that the two women brave. In truth, this adversity is entirely artificial and completely avoidable: were the state to step in and provide social security to the most vulnerable, it would likely offset the lack of access to nutritious food and abject poverty.

“The state is obligated to provide social security to its citizens, which should be seen as a necessary investment and not a burden on the national exchequer,” says Karamat Ali, executive director of the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research.

As the two cases above illustrate, the health and well-being of women and children suffer disproportionately, more than their men counterparts, when families are pushed into a poverty trap due to a natural calamity or death of a breadwinner.

What does social security entail? And how can it protect the most deprived groups, such as poor women, the elderly, the disabled and the casual workers who are often caught in a systematic cycle of poverty and vulnerability from vicious market economy?

Transferring income to women also raises levels of human capital and economic growth, often breaking the inter-generational cycle of poverty. Research studies have proven that for every dollar a woman earns, she invests 80 cents in her family, whereas, men only invest around 30 cents and are less likely to squander resources.

Social security has been enshrined in Article 22 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and discussed in detail in the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Conventions.

Social protection serves to shield vulnerable individuals, groups or communities against the abject destitution and hardships by providing the needy with cover. It has been an integral part of European societies and the cornerstone of their welfare-state model.

International agencies and organisations have established that investing in women’s health and well-being is smart economics as well as very important in combating malnutrition in the household. It is believed that when women hold assets and receive income, the money is more likely to be spent on nutrition, medicines, education and housing. Consequently, their children are more educated and healthier.

Transferring income to women also raises levels of human capital and economic growth, often breaking the inter-generational cycle of poverty. Research studies have proven that for every dollar a woman earns, she invests 80 cents in her family, whereas, men only invest around 30 cents and are less likely to squander resources.

On a broader level, the greater control over household resources by women also enhances countries’ development prospects. A World Bank report published in 2011 claims that evidence from countries as varied as Brazil, China, India, South Africa and the United Kingdom shows that children are primary beneficiaries when women control household income.

Pakistan is amongst the few countries where there is a provision for social security in the constitution. Additionally, Islamabad has also signed and ratified many international covenants and treaties as ICESCR, CEDAW, and the ILO Conventions, which makes Pakistan bound by international law to implement social security measures in letter and spirit.

But the only recent social security programme that has found some success is the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), which reached out to 1.7 million families in the first phase in 2008 through elected representatives. The programme has met more success because the funds are transferred to the female members of the family. The number of families benefitted has increased to 4.7m families in 2014.

This programme has also played an important role in empowering women. Data suggests that there were around 17m women with CNICs in the country in 2007 but more than 23m women received their cards in 2008.

“The majority of its beneficiaries, 4.7m women, have also been using debit cards at ATM machines, which involves their mobility as well as introduction to new technologies and official procedures,” explains Asad Sayeed, a senior researcher at the Collective for Social Science Research, who has researched extensively on the effectiveness of the BISP.

Despite such benefits, the BISP suffers from certain shortcomings such as lack of clearly defined nutrition goals. Farhat Perveen, the executive director of NowCommunites, whose organisation is working on social security, suggests certain improvements in the programme including targeting pregnant women and children under the age of two, increasing the number of trained lady health workers to impart nutrition knowledge to women in remote, rural areas, and, finally, increasing its size and coverage.

Explaining the phenomenon, Priti Darooka, seasoned women’s rights activist and the executive director of Programme on Women’s Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (PWESCR) says, “The government’s policies should recognise women as individual rights holders and not only just as members of family household or group. Their marital status should not have an impact on their entitlements.”

The way government implements its social security programme is in need of a change. Women should not merely be perceived as vulnerable groups in need of state protection, but women should be recognised as economic agents — workers, producers and gatherers, adds Darooka.

If widespread hunger and malnutrition has to be eradicated, the government, NGOs, development sector, donor agencies, and civil society should work together to implement internationally recognised social security policies while recognising women’s role in such transfers of resources.

The writer is a member of staff and tweets @MonizaInam

In Thar, raising women’s empowerment with resin trees

In 2013, under a project by the Society for Conservation and Protection of Environment (Scope), some 2,000 women in Tharparkar district having the country’s highest caloric deficit, a by-product of what it labels a “chronic” food crisis, were engaged in the plantation of the endangered guggal gum tree.

For each plant they tended they were given Rs100 and with each woman growing at least 500 plants on a one-acre plot, they earned a minimum of Rs5,000 monthly. Due to ruthless extraction of resin, the indigenous tree was fast becoming extinct, and thus, conservation efforts to keep the species alive were tied in with women’s empowerment.

“Though completely unlettered, money brought power to the women,” says Tanveer Arif, who heads Scope. Over two years into the project, with the tree almost ready to produce the resin (whereby they will be able to earn more), he has noticed change in the community.

“It has translated into women getting a share in decision-making. They chose to use their income to buy food items like eggs, milk and fruits for their children, stuff they could never afford to earlier,” he says. Along with earning a steady income, the women were also armed with kitchen gardening skills.

Today, instead of feeding their children dried vegetables, many women cook fresh vegetables from their own little vegetable patch. Many have started sending their children to school; one even sent her eldest to college in the nearby city.

With the shift in the balance of power at home, there are fewer fights. “Husbands now treat them with more respect and even help them with household chores, something they never used to do,” observes Tanveer Arif.

But more importantly, with the shift in the balance of power at home, there are fewer fights. “Husbands now treat them with more respect and even help them with household chores, something they never used to do,” observes Arif.

Dr D.S. Akram, a paediatrician heading HELP, a non-governmental organisation working on maternal and child health believes that the family’s nutrition is more directly related to a woman’s employment than a man’s. There is evidence that where women can exercise control over their wages, their earnings are spent on goods which improve the health of children.

Studies upon studies have shown that where the woman has higher economic “value” she receives a greater share of food and healthcare. She may also be able to exert more influence on the household nutritional status. But for a woman to continue to be gainfully employed, factors like: ensuring ‘fair’ wages, improved working conditions, providing access to services such as daycare, healthcare, as well as be able to lighten domestic workload, are important considerations.

The way out: investing in girls’ education

In a country that seeks set formulae out of crises, is there one to get rid of malnutrition in women and girls?

“The formula is quite simple,” says Dr Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, the founding director of the Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health at Karachi’s Aga Khan University. “Put your daughters in school to become food secure and break the cycle of malnutrition that afflicts Pakistani women. The dividends of educating daughters will span several generations.”

It’s globally proven now that keeping girls in schools longer, offering them life skills, training and providing livelihood opportunities and making them economically empowered; informing families about the adverse effects of adolescent pregnancy and allowing girls to grow into women before becoming mothers, will lead to the entire family’s wellbeing and scoring better on the report card on the family’s overall health.

“You do not have to look too far; Bangladesh is a living example,” says Bhutta. “Their government’s investment in education in general and female education in particular [the percentage of women in secondary education in Bangladesh is 55, while in Pakistan it is just 29 has brought about a sea change in the last 40 years. Gender discrimination decreased as women became economically empowered. The number of children a woman has is three, with 67pc of women using modern methods of contraception compared to only 35pc of Pakistani women using any method of contraception and have four children on average.”

“It is important to focus on girls and women if the cycle of malnutrition is to be broken,” says Arshad Mahmood, advisor to SUN-Civil Society Alliance, Pakistan, a coalition of over 100 organisations working for the rights of food and good nutrition of the people.

Obstetrician and gynaecologist, Dr Sadiah Ahsan Pal seconds Mahmood’s argument, and points to nutrition and health deprivation of women and girls in all strata of society. “The choicest of meat pieces go to the male members. Among children, sons get more meat than daughters and the poor mother gets to eat the last and the least of whatever is left over. In poor households, it may very well mean the mother eating a roti with just onions dipped in chutney, rendering her most susceptible to malnutrition.”

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, January 17th, 2016