THE convoluted history of the labour movement in Pakistan is replete with negativities: state oppression by both military and democratic regimes, ethnic and ideological divides among workers, employers’ subversion of genuine workers’ representation through pocket unions, to name a few. Yet it was a brief, two-year flicker of industrial labour struggle that stood out for its promise of labour solidarity and potential for sustained movement, had it not been extinguished by Z.A. Bhutto’s civilian martial law regime in June 1972.

The years 1969-72 were politically tumultuous. The country was falling apart, struggling to hold on to whatever remained. Labour had suffered under the military rule of Ayub Khan (1958- 1969): the Trade Union Act 1926 was repealed, trade unions became dysfunctional, the industrialist class had free rein, workers were retrenched in large numbers, and labour activists were arrested and tried in the military courts.

The workers played an active role in Ayub’s downfall. His successor, Yahya Khan, in a bid to control the situation, promulgated the 1969 Industrial Relations Ordinance — a repressive, exclusionary law that allowed registration of trade unions only under certain conditions. When the PPP won the 1970 general elections in the West Wing, the workers were infused with socialist ideals and the promise of a better bargain.

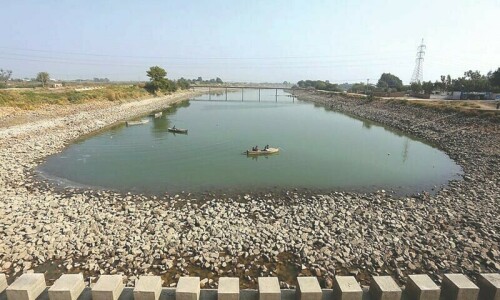

When the PPP government was installed on Dec 20, 1971, the workers’ demands intensified. Labour militancy increased as disillusionment with the new regime set in. Beginning from January 1972, strikes and lockouts in Karachi became routine. What distinguished this phase of labour unrest was the coming together of trade unions and federations of diverse trades, ethnicities and ideologies from both the public and private sectors.

June 1972 marked the end of a briefly resurgent labour movement.

The government was compelled to announce a new labour policy in February 1972 promising certain concessions and an improved legislative framework. But confrontation between the workers and the state and employers continued, only to end on a tragic note. On June 7, 1972, a worker was shot dead by police outside a factory in the SITE area where workers had gathered to collect their wages. The following day, five workers were killed when police opened fire on the funeral procession.

In retrospect, if you sift through the archives, you could identify a number of factors which led to extreme polarisation of stakeholders; a unity among workers that was (and is) rare and the use of force by the state to respond to workers’ grievances. But, as a veteran trade unionist and labour analyst very aptly pointed out to me in a recent conversation, it was the absence of tripartite mechanisms and effective labour institutions that led each party to resort to unilateral decisions and actions. There was no dialogue between the workers and the employers, and the state did not play its role as mediator of conflict: it sided with the industrialists.

After the June 7-8 incident, the government did call the Tripartite Labour Conference. The workers put up tangible suggestions for amendments in labour laws. But the state used the conference as a ploy to placate workers as it had done previously in the first Tripartite Labour Conference 1949 and through the 1950s, and it continued with unilateral decisions to deal with labour unrest. In October 1972, police firing led to four workers being killed in the Landhi industrial area. A few days later, two more workers were shot dead and 50 injured when the police disrupted a workers’ meeting in a labour colony in the SITE area.

Lessons are aplenty, but who pays any heed to history? Till today, there is no evidence of sound social dialogue and effective tripartite mechanisms to facilitate cooperation between two unequal partners. Tripartite mechanisms provide institutional framework for negotiation, consultation and information exchange between and among workers, employers, state officials and other key stakeholders. It leads to dispute prevention, resolution of conflicts and collective bargaining, and creates an enabling environment for economic growth and social progress.

Pakistan ratified the 1976 Tripartite Consultation Convention (No. 144) in 1994. The institutional arrangements for tripartism in place in Pakistan include the Tripartite Labour Conference, provincial standing committees on labour and human resources, provincial and district labour advisory boards, and minimum wage councils.

So what is the complaint about if the institutions are in place? Well, the arrangements do not deliver because the government has failed to establish preconditions for sound social dialogue as outlined by the International Labour Organisation. There are no strong, independent workers’ organisations with the technical capacity and access to relevant information. The government has no political will and commitment to engage in social dialogue. There is no respect for the fundamental rights of freedom of association and collective bargaining. The state institutional arrangements lack genuine workers’ representation. Indeed, it is time to reform labour institutions.

The writer is associated with Piler.

Published in Dawn, June 8th, 2016