Could a smartphone app give Pakistan the push it needs to be polio-free?

After years of frustration battling polio, Pakistan appears to be getting closer to the finish line. Government officials and experts working to eradicate the virus from the country are celebrating the World Health Organisation's (WHO) recent announcement that Pakistan could see the end of polio within a year.

Indeed, there is reason to celebrate. According to WHO data, vaccination campaigns across the country have dramatically reduced new cases of polio from an alarming 306 in 2014 to 54 in 2015. This year, only 11 new cases have been reported so far, and officials are keeping their fingers crossed to make more gains in limiting the scourge.

Despite being closer than they have ever been to reaching their polio-free goal, the government's campaigns still have some problems: areas are often missed by health workers and unvaccinated children continue to fall through the cracks. Some of these areas are avoided for being hard to access and unsafe. In other locales, families are still resistant to vaccinations because of misconceptions about what they are.

In these conditions, persuading a reluctant family to administer the vaccine to their children is no easy task.

Altogether, these barriers give rise to another major obstacle: low health worker motivation.

The average Lady Health Worker (LHW) has up to 200 houses to visit in one day, for which she receives a paltry sum of a few hundred rupees. With such low reward for difficult and often dangerous work, many are unwilling or unable to perform to the best of their abilities.

The result? Missed targets, fewer (and sometimes unsuccessful) vaccinations.

How do we counter this problem?

A study funded by the International Growth Centre offers a simple and inexpensive solution to this problem: smartphones.

Smart solutions

Researchers from UC San Diego, Harvard, University of Southern California and UC Berkley pitched an initiative to the Punjab government with an aim to understand health worker behaviour.

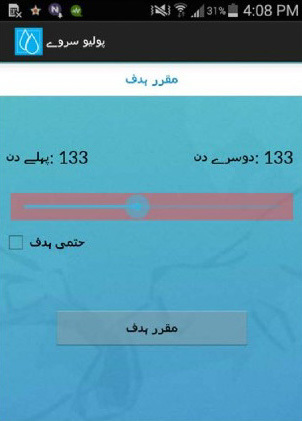

With the support of then commissioner Rashid Langrial, the deputy district health officers in Lahore’s Allama Iqbal and Nishtar Town areas were tasked to coordinate with the university's researchers to facilitate the trial of a special app called Polio Survey.

505 LHWs participated in a trial in the two locales. For the research, they were given smartphones with the app that aims to understand the behaviour of health workers and introduce measures to improve health worker performance.

The women were instructed to set targets of the number of houses they wanted to visit across two days. During the trial, they fed into the app information about the number of children in each household they visited. The information, including GPS data on where they were and what time they visited each household, was received by the researchers in real time.

With this system in place, the researchers began to test the effect of new incentives for motivating the health workers.

Rewarding health workers with bonuses

The first was a pay-for-performance scheme. As part of this scheme, one group of LHWs could receive bonus payment in addition to the flat rate, if they met their target number of households for both days. The other group only received a flat rate.

The result: Smartphone data showed that LHWs working with the possibility of a bonus administered 17% more vaccinations than LHWs with only a flat rate.

Analysing data from this trial, researchers came to a conclusion that would form the basis for the next incentive: LHWs often did not meet the targets they set for themselves.

During a two-day campaign, some LHWs were too ambitious on the first day and fell short. Others put off too much work to the second day, and found themselves rushing to meet their targets.

Rushed service, the researchers speculated, was not smooth service. In a typical campaign where workers tried to meet the target of around 200 houses per day, polio drops could be administered incorrectly and less effort could be made to convince hesitant parents to vaccinate their children.

Implementing a penalty system

To address this problem, a new scheme was introduced which tailored vaccination targets according to each LHW’s behaviour in the first trial. Depending on how a LHW set targets the first time around, the scheme imposed a penalty that either added or subtracted from the value of one visit towards the total goal of 300.

Let’s take the example of a LHW who, during the first trial, decided to perform 200 vaccinations on the second day, so she could do less on the first day. For her, each vaccination on the second day would count as a fraction of one vaccine. She would have to administer more vaccinations to reach her goal. If this worked, she would divide her work evenly between the two days, to avoid being overburdened on the second day.

The result: The researchers found that tailoring vaccinations according to personal preferences increased the likelihood of adopting a more balanced schedule by 33%.

There are limitations to these results. Firstly, replicating these policies in districts with different political, social and economic contexts may not yield the same results. Another problem was that LHWs were unaware that their tailored targets for the second trial were based on their behaviour from the first trial. If they knew this, there is a possibility they would alter their behaviour to game the system.

But the researchers say that as long as incentives continue to be adjusted based on the most recent vaccination campaign data, this should not be a problem.

Dr Mohammad Akhtar, the deputy district health officer of Iqbal Town maintains that providing technology to workers who are actually on the ground can be very effective, "That is where it will have maximum use," he says. He cautions, however, that "some people take time in grasping the use of technology so training should reflect that".

Health workers report that this technology may also help make them appear more credible to parents of children. "Using smartphones in front of parents legitimises our presence," says Chand Sultana, a LHW who participated in the trial.

The researchers have recommended to the government that adopting smartphones for monitoring LHWs could offer a viable solution for increasing vaccination coverage. But it will take time — and more trials — before the government rolls out the system on a large scale.

Today, Pakistan is one of the only two countries where polio is endemic (the other country being Afghanistan). There is certainly a need to understand why certain areas still remain unvaccinated. Perhaps most valuably, the smartphone app for health workers can help provide this data to the government.

The author works with the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR), which disseminates the research. CDPR is also funded by the International Growth Centre.

Header photo courtesy AFP