THE outpouring of anger and revulsion at the recent spate of murders of young women who tried to exercise their basic rights will go to waste if the causes of increase in such cases are not seriously tackled.

The first thing to be noted about these murders is the escalating level of brutality. The young woman from Murree who was severely tortured before being set ablaze by her closest relatives was punished for refusal to marry against her wishes.

In Kasur a young woman paid with her life for arguing with her husband and the latter was helped by his female relatives to burn her alive.

A woman in Lahore strangulated her daughter for taking a spouse of her choice and then set her on fire. In another incident in a village near Lahore, a man shot dead his daughter for having exercised her right to marry of her free will a year earlier, along with her husband and a bystander.

It has not been possible to make women-friendly laws due to the orthodoxy’s opposition.

Apart from confirming the continued brutalisation of society these incidents reveal a growing intolerance for women’s rights not only among men but also among women themselves.

While civil society organisations, women activists and some politicians have felt outraged, the public outcry has not been as loud as it is sometimes in other cases of violence against women, such as gang-rape under panchayat orders. Obviously, a section of society, including women, has been influenced by the orthodoxy’s opposition to women’s rights to the extent of justifying violence against all those who rebel against unjust constraints.

Oddly enough, in the debate over the surge in violence against women, the remedy is generally sought in developing new legal instruments to punish the culprits. This became abundantly clear from the brief debate in the Senate a week ago, thanks to chairman Raza Rabbani’s decision to suspend the business of the house and invite members to discuss woman-burning. All the members who are reported to have joined the discussion backed the chairman’s call for a strong law to punish the burning of women to death.

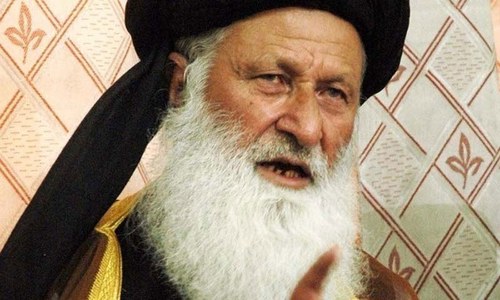

The Senate proceedings, though welcome, underscored the limited nature of the debate. First, no member of a religious party is reported to have considered the burning of women worth talking about, and that betrays how far Pakistan’s religio-political elements have gone in their psychopathic hostility towards women. Secondly, except for one senator’s reference to the role of the Council of Islamic Ideology in increasing society’s hostility towards women, the honourable senators seemed reluctant to discuss the causes of the failure of laws to protect women.

It is perhaps not correct to assume that there is no law to deal with burning women to death. The offence is recognised as premeditated homicide punishable by death. What is needed is only a reversal of the process whereby rich criminals or gangsters can escape punishment by forcing the victim family to forgive them.

The real issue is the fact that it has not been possible to make women-friendly laws, nor to fully implement such laws, because of the orthodoxy’s opposition. Only the other day the prime minister’s special assistant for law and human rights revealed how two bills, one on ‘honour killing’ and the other on rape, have been stuck in parliament due to the opposition of a single religio-political party, which is, incidentally, as indispensable an ally of the present government as it was of the previous one.

The seeds of misogyny in Pakistan were sown 66 years ago when the authors of the fundamental rights chapter of the Constitution ignored Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which upholds the right of both women and men to marriage by choice and equal rights of spouses. (The article has been excluded from the fundamental rights chapter in all of Pakistan’s constitutions.) Ever since then, the state has acted on a one-sided understanding with the most obscurantist among the religious lobby that women’s fate will be decided by the latter.

That women’s rights will forever remain subject to the veto of those who abuse religion for political purposes is a proposition the people of Pakistan cannot afford to accept. Their right to challenge the professional clerics’ invocation of religious injunctions cannot be denied. Also, the rise in woman-bashing in Pakistan since the Zia period, to a greater extent than in any other Muslim country, is a question the ulema must ponder over.

The reality is that the combination of patriarchal constraints, feudal emphasis on male supremacy and misogyny has left Pakistani women with little space to even breathe. That the party of Mufti Mahmud, who had backed the Family Laws Ordinance, should be represented by Senator Hamdullah only shows that arrogance has been added to the obscurantist’s armoury.

Unfortunately, the state has failed to convince the religious scholars of the disastrous consequences of a retrogressive interpretation of the scriptures for women, Pakistan society in general, and for Islam itself. One hopes that the few religious authorities who have begun to denounce ‘honour killings’ as un-Islamic will devote more time to converting their community of ulema than informing laymen of their sympathy for women.

However, a vast world of opportunities for women lies beyond the religious rigmarole in which the state has trapped itself; women can be enabled to fulfil their hopes through a strong social force of enlightened women and men. Such a force will surely materialise if women are given weightage in their share of jobs in the education and health sectors, are allowed a leading part in the local bodies, and if their role in policymaking institutions and services, including the judiciary, is progressively enhanced.

Much of this can be done if the state discovers its will to move earnestly against misogyny.

Published in Dawn, June 16th, 2016