Of human organs, desperate poverty and greed

For a hospital, this centre for kidney transplants appears to have a lot of secrets.

“No photography allowed”, reads a prominently displayed notice by the entrance.

In the waiting room, an employee curtly tells the people present to not take any photographs and to switch off their cell phones. To confirm compliance, he even walks around peering over people’s shoulders.

At least two security cameras are attached to the ceiling.

One of the doors leading from the room bears the sign “Society of transplant physician [sic] and surgeons (head office)”.

These are not regular OPD hours and there are only about a dozen people in the waiting room. Leaning back against a two-seater is a young woman accompanied by a little boy about six years old, solemnly eating a packet of crisps. Her hands are rough and calloused, and her complexion has the sunburnt look of someone who works outdoors all day. A plastic bag with documents lies next to her.

The hospital staff asks that cell phones be left outside with them before the patients and their attendants go in to see the doctor.

In his office, the transplant surgeon, sporting a thick, jet-black moustache and wearing a flashy, diamond-edged gold watch, is in the midst of a consultation. The patient, who has developed liver problems, is referred to another doctor, a retired colonel, who the surgeon says, “sees all our patients”.

Turning to this reporter, unaware he is actually speaking to an undercover journalist, the surgeon agrees that charges for transplants are high:

“It’s the media that’s created such hype about it. They talk about the donors, whereas we say the problem is not about the donors, it’s about the patients.”

A seven-day package, he says, which includes medication, transplantation and hospital stay costs Rs1.8m, including Rs600,000 if a donor is arranged from outside.

“Unrelated donors becomes a complicated issue, there are lots of legal aspects which we have to cover. Because of all this, the cost has gone up.”

RISE OF THE ORGAN TRAFFICKING RACKET

Organ trafficking is a practice that involves organs – almost always kidneys – purchased from living donors. It was criminalised in Pakistan when the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Ordinance was promulgated in 2007. That briefly led to a steep drop in transplants using vended kidneys, estimated at around 2,000 per year earlier.

Despite aggressive efforts mounted by the influential pro-organ trade lobby to derail the Ordinance before it could become law, the anti-organ trade campaigners won the day and in 2010, the National Assembly and Senate passed the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act.

The law lays emphasis on organ donation that is “voluntary, genuinely motivated, not under duress or coerced”. It says that if a donor is not available within a patient’s immediate family (parents, siblings, spouse and offspring), “a non-close living blood relative” willing to donate his organ can do so provided an evaluation committee of the transplantation facility concerned is satisfied that no financial consideration is involved. Only in very special circumstances — such as unavailability of a family donor — can a non-related person donate an organ, provided there is no financial compensation.

Contravention of this law is punishable with up to ten years imprisonment and a fine extending to Rs1 million.

Under the 2007 ordinance, a national body — the Human Organ Transplantation Authority (HOTA) — was formed to register, regulate and monitor institutions offering transplants in the country. After devolution, provincial HOTAs were set up to discharge this regulatory function and the erstwhile federal HOTA assumed responsibility for Islamabad Capital Territory alone.

The 2010 law appeared to have brought down the number of illegal transplants — that is, until two or three years ago. Since then, say several leading urologists in the country, organ trafficking has once again become a flourishing racket.

WEB OF HOSPITALS

The institution in Rawalpindi profiled above is far from the only offender. Multiple sources as well as kidney donors to whom Dawn spoke pointed to another hospital in the same city, as well as several in Lahore and Islamabad, and certain urologists and nephrologists affiliated with these institutions who carry out transplants using vended kidneys.

There are also a number of other medical facilities, some of them fly-by-night clinics in rented premises, involved in this illegal, unethical practice that preys upon the poorest of the poor.

Given the areas where such criminal activity is centred, Punjab HOTA and federal HOTA, as well as the evaluation committees giving the go-ahead for these illegal transplants, have much to answer for.

Contrary to the claims of parties involved in organ trafficking, it is greed, not altruism that drives the business.

“In a country like Pakistan, where families tend to be large, suitable related donors should be easily available,” Dr Philip O’Connell, president of the Transplantation Society of Australia, told Dawn while on a working visit to Karachi.

“If you have siblings, there’s a 25pc chance you’ll have a perfect match among them, a 50pc chance there will be a 50pc match, and a 25pc chance there will be a zero match. But even with a zero match, transplants can be carried out in most cases, provided a few conditions are met, such as the same blood group. To say an organ will have to be purchased because there’s ‘no match’, it’s just a game.”

Another Australia-based kidney specialist accompanying him, Dr Jeremy Chapman, who is recognised as one of the foremost experts in the field of transplantation, added: “On the one hand, you have desperate, uninformed, wealthy patients who think they’ll die without a transplant; on the other, there are profit-driven doctors who will take those patients to the cleaners.”

TRANSPLANT TOURISM

An email dated Dec 9, 2014 from the Kuwait Transplant Society president, Dr Mustafa Al-Mousawi, and available with Dawn, reads:

“Was just talking to a… patient who came back yesterday from Pakistan. He is Saudi and was transplanted [along] with another Saudi and five Omanis in one week in Islamabad in villa which he described as clean and furnished like a hospital…He says surgeon performs two transplants daily for patients from the ME (Libya, KSA etc).”

Dr Mousawi told Dawn that no patient went to Pakistan for transplants from 2008 to 2011 (see graph), which he believes was because of international pressure and the legislation passed in 2007 and 2010.

Such ‘transplant tourism’, which refers to people coming to Pakistan to get transplants done with organs purchased on the black market, is the most lucrative sector of this racket with each transplant costing the patient around $100,000.

Because of the legal implications, particularly when such large sums of money are at stake, those involved go to great lengths to stay below the radar, including carrying out the transplants in temporary, rented premises.

An email dated Feb 14, 2016 from Dr Chapman about a transplant patient who visited Pakistan for the procedure, reads:

“[H]e was operated in a makeshift ‘house/hospital/clinic’ with an epidural anaesthetic. Conditions he … describes as terrible (“couldn’t wait to get out of there”). … Many similar recipients were being dealt with — US citizens etc.”

These cloak-and-dagger operations can be risky for patients in other ways too. In an email to Dawn, Dr Mousawi wrote:

“Most patients are told to return to Kuwait within few days after surgery, often with catheters and drains still in place. Once the patient is out of their sight they are not their responsibility anymore. This is very dangerous for transplanted patients with low immunity to infection.”

Other accounts mention patients as being taken from their hotel “through different routes every time”, “being instructed to wear Punjabi clothes” and that “the middlemen kept changing their mobile numbers”.

Meanwhile, a hospitality industry has been functioning for years at a stone’s throw from the abovementioned Rawalpindi hospital to accommodate transplant patients.

There are four hotels around the corner — Noor Mahal, New Noor Mahal, Decent and Royal Palace — and a number of houses for rent in the vicinity specifically catering to transplant patients.

According to the proprietor of the 20-room New Noor Mahal, each twin-bed room rents for Rs30,000 or Rs45,000 per month (without meals) depending on whether it is air-conditioned or not. “At the moment there are five or six families here,” said the proprietor. “Most stay for at least three weeks, sometimes longer.”

Transplant recipients are dependent on immuno-suppressant drugs for the rest of their lives to reduce the chances of organ rejection, so they need regular follow-up consultations and tests.

To that end, some commercial transplant patients from Karachi when they return after their operations, register with the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation, the city’s leading public sector hospital in this field. According to records maintained by SIUT — which has been promoting ethical organ transplantation in the country — six commercial transplant recipients registered with the Institute in 2014; nine registered in 2015. These were the highest annual figures since 2007 when the transplant ordinance was promulgated.

And this is only a partial picture: these patients are mostly Karachi-based, and generally from the lower income segment of society. Those from more affluent backgrounds often opt for facilities in the private sector.

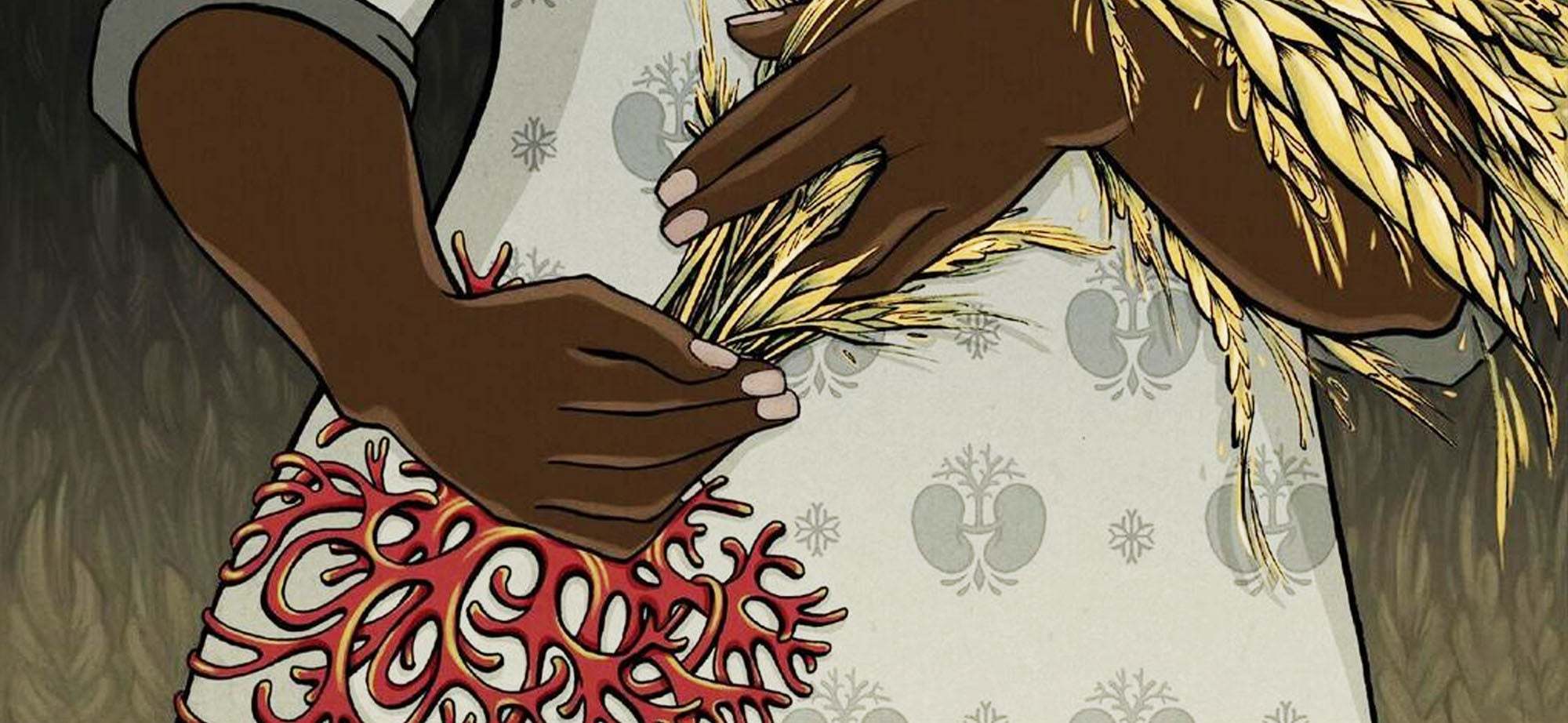

THE DONORS: POOR, DESPERATE, IN DEBT

About 200 kilometres from Rawalpindi is the town of Kot Momin. Its proximity to the international standard motorway that connects Islamabad with Lahore throws into stark relief the chasm between the modern and the medieval in certain parts of Pakistan.

Lush fields of corn and rice stretch across the landscape, as do orchards of malta. This is Pakistan’s ‘citrus basket’: the crop earned Pakistan around $365 million in foreign exchange last year.

Yet there is dire poverty here, among the bonded labour that toils on the farms, at brick kilns and in the homes of the landowners. These modern-day slaves work to pay off crushing debts in an opaque system of usury that ensures generations-long servitude.

Such deprivation is the natural hunting ground of ‘agents’ — affiliated with hospitals that conduct illegal transplants — seeking people desperate enough to sell their organs.

A study cited at a Harvard conference in 2008 found that:

70% of donors in Pakistan were bonded labourers

90% were illiterate

88% had no improvement in economic status from the donation

98% reported a subsequent decline in health, including chronic pain from large incisions.

Several villages in the Kot Momin area had become notorious for vended kidneys before the organ transplantation law was passed. According to residents, the media attention in the mid to late 2000s led to agents looking for donors in other similarly deprived parts of the country.

One of the locals, Mohammed Zafar said, “There was an agent here named Khalid who had arranged for scores of people to sell their kidneys, but he ran away after an arrest warrant was issued for him. Once it was almost a fashion here to sell a kidney and buy a motorcycle or a television with the money.”

However, bonded labourers willing to sell their kidneys can still be found here, as can agents who continue to scout for them. “Before, one would get around 60,000 rupees for selling a kidney. It’s gone up since then,” said a resident.

According to locals, the agent of the moment is Afzal, who visits from Rawalpindi, armed with a portable kit for basic blood sampling.

Halima, a young mother of seven, sold her kidney eight months ago for Rs180,000.

Her children have never been to school: the government school which offers free education is too far. Her family owes Rs400,000 to the zamindar on whose fields her husband works seven days a week. Twelve years ago, two months after their marriage, her husband had undergone the same procedure. He had taken a loan from the landlord for his nuptials, and selling his kidney seemed like a good way to defray some of it.

“First Afzal [the agent] took me to court where I had to put my thumb impression on some documents. The operation took place at Rawalpindi’s dil hospital [as the facility is known in local parlance],” said Halima. “They kept me there for four days, and discharged me with some painkillers. The doctor’s name was Khalid.” (Unknown to her, she was in the third month of her pregnancy at the time: no one at the hospital informed her of the fact.)

According to a local journalist, donors are sometimes made to submit affidavits claiming they are having their failing kidneys removed. “It’s all very clandestine. The police are not interested in looking into it, neither is the administration.”

Halima was fortunate her incision healed well. When donors develop complications, such as incisions becoming septic, sutures tearing, etc they have to bear their own medical expenses.

The tehsil hospital, said villagers, offers substandard care, and donors in need of medical attention opt for private ‘doctors’ — in reality, smalltime compounders with hole-in-the-wall ‘medical practices’.

A local doctor who was sympathetic to their plight, used to treat them for free. But two years ago, after repeated threats from religious extremists in the area — he was Shia — he closed his practice and left the country.

Twenty-seven-year-old Rashid, who suffers from night blindness, sold his kidney six weeks ago.

Relatives said he was in such despair over the debt he owed his landlord that he had been contemplating suicide. But even selling his kidney did not appear to have brought him relief. Hunched on a charpoy, he seemed weighed down with misery.

Occasionally wiping his rheumy eyes with a cloth, he did not look up while speaking. The eight-inch scar from his surgery had not quite healed, and he grimaced with pain as he lifted his shirt to show it. He had not yet been able to resume working in the field.

According to Rashid, the agent Afzal handed him over to another agent named Cheema, who took him for his initial test to a laboratory at Rawalpindi’s Pir Wadhai Mor. The transplant took place in the evening a week later at a hospital in Rawalpindi.

“A doctor named Zahid operated on me,” he said. There, he came across another donor, who was from Sheikhupura. Rashid was discharged after three days with two painkillers, no prescription and no advice on any precautions he needed to take in the post-operative period.

“Afzal had promised me Rs250,000 but gave me only Rs150,000.” Asked what he did with the money, Rashid said: “I handed it over to the zamindar.” Despite knowing at what cost he had obtained that cash, the landlord pocketed the entire amount. Rashid still owes him Rs300,000. Until he pays that off, he and his family remain indentured.

Ejaz, a bonded labourer working at a kiln in Lahore’s Batapur area, sold his kidney 18 months ago.

“I wanted to free myself of debt bondage, so it seemed like a good idea,” said Ejaz. “I went to [a hospital in Lahore] and had it done. The buyer was an Arab, and the hospital paid me Rs200,000.”

He soon discovered that selling his kidney was simpler than extricating himself from debt bondage.

The brick kiln owner took the money Ejaz had ‘earned’ but informed him there was still Rs.400,000 outstanding against him. Ejaz remains at the kiln to this day.

Last week, an FIR was filed by one Tasleem bibi at Mela police station in Kot Momin tehsil alleging that Mohammed Afzal took her to Akram Medical Complex in Lahore where her left kidney was removed.

According to the FIR, she was paid Rs300,000 out of which Afzal kept Rs50,000.

Dr Waqar Ahmed, a nephrologist at Akram Medical Complex, told Dawn that Tasleem bibi was the kidney recipient’s servant and that both parties had gone before a judge, the recipient to declare she had no family donor, while Tasleem bibi had stated that no compensation was involved. “HOTA also interviewed them, took video statements, and gave them permission.”

A senior police official told Dawn that the police’s special branch is investigating.

LOCAL RECIPIENTS OF VENDED KIDNEYS

Dawood Waheed, 47, was deeply dejected after his consultation with a urologist in a Rawalpindi hospital early last year. The doctor had told him his wife was not a match and he had to find another related donor for a transplant. But Mr Waheed had no hope left. “One brother suffers from hepatitis C, another has himself had a transplant and the third had refused to give his kidney.”

In the foyer, he was approached by one of the hospital’s employees who told him there was someone outside who could help him. When he stepped out of the gate, a man seated in a taxi beckoned to him and told him he could get him a kidney.

The entire process, from that meeting to the transplant in April 2015, took three months and cost him around Rs.2m, which he managed to collect with help from relatives. That amount included Rs500,000 he paid to the man who obtained a donor for him.

When he went back to the same urologist after having agreed to purchase a kidney, the doctor did not ask him anything about the donor. “I wasn’t surprised. They’re all mixed up in it. Their lower staff does all the groundwork,” said Mr Waheed. He has no idea who his donor was.

Samir Ahmed, who works at a medical facility in Karachi, had his transplant done one and a half years ago at a Rawalpindi ‘kidney centre’. He suffers from a congenital kidney disorder that renders his family unsuitable as donors. “The hospital said if they arranged a donor for me, the cost would go up from Rs.1m — which they would have charged had I brought a donor myself — to Rs1.7m.”

After his transplant, Dr Ahmed stayed at the hospital for a week. “The place was full. There were lots of foreigners too. Close to my room — there were between 15 and 20 rooms, all private — there was a Saudi, a Libyan and a Bahraini.”

According to him, a lot of documentation had to be completed before the transplant including stamped affidavits to show he had no related donor. That was handled by his brother and his wife, given Dr Ahmed’s critical condition at the time. However he added, “They definitely must have had them sign documents saying they weren’t giving monetary compensation to the donor, whom we never saw.”

Did he believe the donor was paid? “Of course. 100 per cent.”

AIDING AND ABETTING A MEGABUCKS RACKET

“Having a law on the books and not implementing it has done more harm than good,” said Dr Saeed Akhtar, who is professor of urology and director of transplant surgery at Shifa Hospital in Islamabad as well as president of the Transplantation Society of Pakistan.

“The quality of transplants has gone down, while the cost has gone up. From Rs500,000 to 600,000, it now costs Rs1.5 to 2m. After all, they have to cover all the illegalities.”

The impunity with which the racket is carried out is no secret in the community of kidney specialists, both local and international.

An email dated April 21, 2016, from Dr Francis Delmonico, a world-renowned transplantation expert and executive director of the Declaration of Istanbul Custodian Group — an international initiative to address organ trafficking and transplant tourism — was scathing in its condemnation.

Referring to a 60-year-old woman who had become “acutely ill” after returning home to Vancouver after a transplant in Pakistan, he wrote: “…she had every expectation that she could buy a kidney in Pindi. Because that is the track record for Rawalpindi — everybody knows it, including the Pakistani government.”

However, the Punjab police appears unaware of the scale of the problem.

“This is frankly not an issue that is on our radar,” said Dr Haider Ashraf, DIG Operations Lahore. “Moreover, we can only look into a case on the basis of a complaint. That’s not happening, not even on the part of the health authorities.”

Several years ago, following the transplantation ordinance, law-enforcement personnel carried out some raids against facilities engaged in this outlawed practice. After that, however, a lull has descended.

According to police, although 63 people were arrested between 2013 and 2016 in Lahore district on suspicion of involvement in organ trade, only two cases are currently being investigated, one from 2014 and another that was registered this year.

As per police records, only 12 instances of illegal organ transplants have occurred since 2013 till date.

The fact is that those involved in this business are well-connected individuals who consider themselves above the law.

In 2010, a HOTA enquiry team — there was only one HOTA at the time — accompanied by police personnel, visited Al-Sayed Hospital in Rawalpindi on account of repeated claims that doctors at the facility, which is owned by a retired colonel, carried out transplants using vended kidneys. However, members of the team found themselves stonewalled.

Hospital staff told them their computer system was down so they could not share details of their transplant cases. When asked for hard copies, they said they didn’t keep any.

“Then there were six or seven big operating theatres on the premises but strangely, no operations were being performed there although we went in the daytime,” said a former member of the team. “The people there said operations take place in the evening, which was very odd.”

Despite recording their findings in a report to the health ministry, no action was taken.

Various organs of the state — including the health bureaucracy, local government, police, etc —all have a price for colluding in the racket.

An Islamabad-based urologist narrated an incident that took place a week ago.

“My colleague in Pindi was approached by what was apparently a middleman offering Rs1.6m ‘packages’ to do unrelated living donor transplants, with the proceeds to be divided between the doctor, police, HOTA, and the donor. ” Not only that, the man said he would also have FRCs — Family Registration Certificates issued by the National Database Regulatory Authority that show an individual’s family tree — prepared accordingly to show donors as being related to the prospective recipients.

A urologist at a clinic in Islamabad’s Blue Area stated in the presence of this reporter that it was possible to carry out a non-related transplant and that his nephrologist would line up everything, including the permission from HOTA.

Speaking with Dawn, Dr Faisal Masood of Punjab HOTA said:

“We don’t allow unrelated transplants. I interview the donor and recipient in each and every transplant case to ensure there is no duress or money involved.”

However, according to him, the inspection team makes scheduled, not surprise visits, and checks only “technical” matters.

When asked if Punjab HOTA had taken any action against any medical facility for carrying out illegal transplants, he said with considerable vehemence that they could only do so if a complainant came forward “with evidence” and laid the blame squarely at the door of the police who he said were bribed to keep quiet.

When asked whether Punjab HOTA was planning to take any action against hospitals about whom complaints had been received, he said that three hospitals, including Al-Sayed in Rawalpindi, and Badar and Genex in Lahore were currently “under scrutiny”. Interestingly, Al-Sayed was recognised by Punjab HOTA only this May as a transplantation facility.

There was a point when it appeared that the federal HOTA — whose mandate was later limited to the Islamabad Capital Territory — was on the cusp of achieving some real progress in the country’s transplantation programme. During 2013, while it was still engaged in policymaking on a federal level, it laid down the framework for a deceased organ donor programme: this included the development of organ procurement organisations and a national organ sharing network, with the army promising helicopters to fly out organs to wherever needed in the country.

Systems were put in place for monitoring transplantation centres through inspection teams to ensure compliance and prevent illegal transplants; and a central database was set up where cases from all around the country could be logged.

Unfortunately, helped along by the administrative disarray that hobbled many government institutions after devolution, HOTA fell prey to corruption and nepotism, the typical afflictions of bureaucracy.

Instead of strengthening the deceased organ donation programme that would have addressed the issue of organ shortage used by the pro-organ trade lobby to justify commercial transplants, HOTA became a rubber stamp for all manner of irregularities that aided and abetted the organ trade.

In 2014, a three-member official committee was constituted to look into personnel appointments made at HOTA from September 2012 to May 2013 by the Authority’s then administrator Dr Fazle Maula. (The latter was in that post until a few weeks ago.) The committee in its report dated July 3, 2014 concluded two to one in its report, “…that against the 17 sanctioned/vacant posts, 85 persons were illegally recruited and set the worst example of favouritism and nepotism.”

Annexures to the report show multiple recruitments —14 in some places — on single posts as well as appointees with educational qualifications far short of eligibility criteria.

According to a source, “Many of them were personal servants, cooks and security guards of secretaries in the Capital Development Authority. What would they know about transplants, let alone illegal transplants?” Incidentally, Dr Suleman Ahmed, monitoring officer at Federal HOTA is Dr Fazle Maula’s nephew.

On its Facebook page, Federal HOTA declares it “is committed to work against the menace of organ trade” and that it has “issued an Advisory letter to foreign office regarding provision of a mandatory certificate by foreigners visiting Pakistan that their stay in Pakistan will not involve any illegal activity such as seeking a donor for organ trade”.

The Supreme Court is currently hearing a petition about proliferating illegal transplants in the country. Proceedings have been heated, with allegations flying back and forth.

“It is not true that those who are against the trade in organs disregard people in need of kidney transplants. Such patients have a backup, which is dialysis,” said Dr Mirza Naqi Zafar, general secretary of the Transplantation Society of Pakistan. “At the same time, we also need a proper deceased donation programme.”

MNA Kishwar Zehra, who was one of the principal campaigners behind the transplantation law, has introduced an amendment in the National Assembly that would simplify the procedure for deceased organ donation from individuals who lose their lives in vehicle accidents.

As part of her research for the earlier legislation to regulate transplantation in the country and promote ethical practices, she met scores of kidney donors in villages across Punjab.

One incident still brings her to tears.

In a village close to Kot Momin, she met a woman who narrated how she sold her kidney in Islamabad.

“Did you manage to pay off your debt?” she asked her.

“No,” said the woman. “Not yet.”

Then she glanced over at her daughter next to her and said: “She’s too young right now. When she’s a few years older, I’ll sell her kidney. Maybe then we’ll be free.”