It is a universally acknowledged truth that an overwhelming majority of Karachi’s immigrant intellectuals once lived in Nazimabad. Talking about it invariably turns into a litany of famous names who resided there.

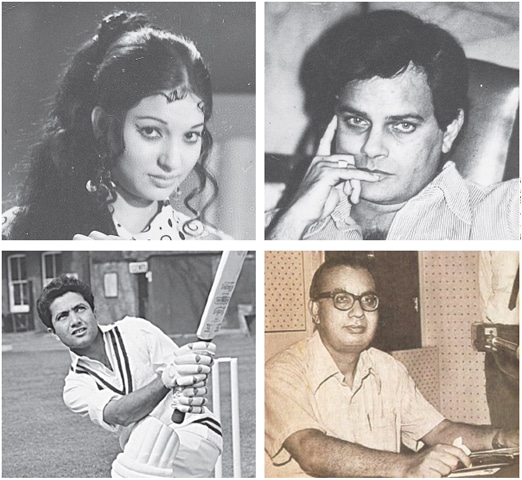

Some well-known former Nazimabad residents include artists Sadequain and Iqbal Mehdi, Justice Lari, actor Shakeel, film-maker Saeed Rizvi, actress Sangeeta, writers Mukhtar Zaman and Ibn-i-Insha, scholar Alia Imam, poet Ahmad Siddiq aka Majnun Gorakhpuri, journalist Mujahid Barelvi, columnist Nasrullah Khan, singer Salman Alvi (then known on radio as Salman Mian the banjo player), plastic surgeon Dr Mohammad Jawad (of Saving Face fame), and Aale Raza, brother of Hashim Raza.

This isn’t surprising as from the 1950s to 1970s Nazimabad was the centre of India’s Muslim culture and an inheritor of Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb. Partly this has to do with the way history unfolded: most refugees to Punjab or Bengal, who fled persecution, moved from the Indian part of the province to the Pakistani. As a result, homogeneity of language and culture in Lahore or Dhaka was maintained.

From the 1950s to 1970s, Nazimabad was the hub of intellectual and cultural activity in Karachi

Immigrants who came to Karachi, however, were different. Many did come due to unrest in their hometowns but most came for opportunities in a new nation. They originated from cultural centres of the subcontinent such as Lucknow, Delhi, Amroha and Hyderabad.

Among these new immigrants was the first generation of educated, socially-mobile Muslims; graduates of Aligarh or Osmania University who had played an important role in the Pakistan movement. As Jaun Alia once acidly remarked, “Pakistan ... ye sab Aligarh ke laundon ki shararat thi” (Pakistan — this was the mischief of boys from Aligarh).

Karachi’s character, till then, was that of a mercantile port city. The Urdu-speaking intelligentsia altered it dramatically and engineered a mini-renaissance.

Consider, for instance, Muslim members of the Indian Civil Service. At Partition, there were 980 ICS officers of which 468 were Europeans, 352 Hindus, and 101 Muslims — the rest were from other communities. Karachi, as the country’s capital, got the bulk of Muslim ICS officers. Along with Urdu-speaking intellectuals, they settled at the outskirts of Karachi in areas such as PIB Colony, Martin Road, and Jehangir Quarters where small homes were allotted to them.

By 1951 the city’s population had gone from 400,000 at independence to one million. Soon residential areas were marked out. One of these was the area that stretches from Paposh Qabristan to Liaqatabad Flyover abutted by Orangi Stream and Gujar Nala.

In the days before Partition it was an arid piece of land, 10km from Karachi’s centre and dotted with Sindhi and Baloch villages. In 1950, however, the government bought the land from tribal leader Masti Brohi Khan. By 1952 the locality was marked out and named Nazimabad after Khawaja Nazimuddin, the second governor general of Pakistan.

Another new locality, Liaqatabad, was named after Liaqat Ali Khan.

Nazimabad’s plots were sold at reduced prices to immigrants who had been characterised as ‘Mohajirs’ in the 1951 census. The new residents were given plots at subsidised rates of 3.5 rupees per square yard, most of which were 216 square yards but the ones off the main roads could go to 600 square yards.

The immigrants only bought one even if they could afford many as they knew that a land rush would have meant that some would be left out. The strong values they espoused would not allow this sort of business-minded thinking.

For the immigrants this was the chance to reclaim the lives they had left behind. As Dr Asif Aslam Farrukhi said, “Having a house in Nazimabad was a sign of affluence and development. It was about putting down roots and ownership. A home was critical and for many middle-class, educated immigrants it was their first owned property in Pakistan.”

Nazimabad had a strong sense of new beginnings. In this spirit writer and scholar Shan-ul-Haq Haqqee named his house Shua-i-Saaz (first ray of creation). Other people named homes to carry on a tradition of honouring the place of origin or an ancestor.

There was a great desire to transplant culture of immigrants’ towns and the architecture reflected that. Homes in Nazimabad featured verandas and gardens that were reminiscent of houses dotted across North India. Liminal concepts and classic indigenous styles harmonised to produce a new style that featured art deco, Mughal columns and external spiral staircases. Open spaces were critical since electricity was not available till 1956 and the whole family often slept in the veranda or dalaan to escape from summer’s heat.

By the mid-1950s Nazimabad was well-populated. Poets, artists, civil servants and other members of Muslim intelligentsia created a heady environment not seen since. Nazimabad of that time could be compared with Paris’s locality of Montparnasse in 1920s when Picasso, Hemingway, Becket and many other legends lived there.

Walking on the wide lanes and tree-lined streets you could have bumped into Sadequain who was living in his home ‘Sibtain Manzil’ located in Nazimabad Block 2. If you were looking for prose then writer Ibn-i-Insha was nearby for a quick discussion on one of his travelogues. Politicians, doctors, lawyers and educationists all often resided on one street.

Today it’s difficult to imagine the cultural environment. Houses would stay unlocked late into the night without fear of robbery. Everyone knew each other and gathered either at homes or places like the Nazimabad Club where evenings would be spent playing bridge or watching a theatre production in the auditorium.

If they were fond of reading they could head to one of the many libraries in Nazimabad. Ghalib Library, with its 3,000 books and 375 literary magazines, was a popular destination. The double-storey structure was built by Habib Bank under the guidance of Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Mirza Zafarul Hasan.

The two had worked earlier to set up the Idara-i-Yadgar-i-Ghalib and Ghalib Library was the result of their vigorous efforts. It had the unique distinction of its tin sign painted by Sadequain who also made a painting for its interior. Literary personalities would read out or give lectures there and Ghazi Salahuddin remembers being treated to talks by Ismat Chughtai, Sibte Hasan, Josh Maleehabadi, Jilani Bano, Sardar Jaffri and many others.

Walking on the wide lanes and tree-lined streets you could have bumped into Sadequain who was living in his home ‘Sibtain Manzil’ located in Nazimabad Block 2. If you were looking for prose then writer Ibn-i-Insha was nearby for a quick discussion on one of his novels.

For movie lovers Nazimabad was a veritable paradise and had several picture halls with general enclosure at six annas and a box seat for one rupee. There was Chaman Cinema towards the Pak Colony side and Naya, Relax, Liberty in Block 2. Shalimar was at Petrol Pump Chowrangi, named so because the pump installed there in 1956 was the first in that area, and further down was Regent Cinema.

During Muharram it was a hub of marsia recitals and majlis events at which Rasheed Turabi and Z.A. Bukhari would recall the martyrs of Karbala. In the days when PTV would be off on every Monday, Ashura once fell on Monday. Such was Turabi’s influence that one message from him made sure that the Sham-i-Ghareeban telecast would go ahead as it always did.

With such a large population of educated people it was no wonder that academics were taken seriously. Happy Dale School in Block 4, established in 1951 produced some leading alumni, as did Government Boys Secondary School in Block 2. On one side of the school was Government College Nazimabad, which was a bastion of student movements of 1960s including the one against General Ayub Khan.

Another place of learning was Sir Syed College which had different branches for men and women. Salma Zaman, the principle of Sir Syed Girls College, strongly believed in female education. Another was Nazimabad School of Art in Block 1, the first art school in Karachi. Opened in a house by Rabia Zuberi it later became the Karachi School of Art.

Nazimabad also has an enormous sports legacy. Badminton national champion Minhaj Ahmed started playing the sport in the street outside his home. Table tennis and bridge teams were also nationally competitive but the sport that defined the neighbourhood was cricket.

The Mohammad brothers, Hanif, Wazir, Mushtaq and Sadiq all represented Pakistan while Raees played first class. Sadiq Mohammed recalls the time when he played club cricket in Nazimabad, “We used to live in Nazimabad Block 1 [from 1963 to 1986] and I represented Pak Crescent Club. Across the road was Saadat Ali, the club owner, whom we used to call ‘Bhai Jaan’. Hanif Bhai, Shoaib (nephew), Asif Iqbal, Zaheer Abbas were all involved in Nazimabad’s club cricket. People used to come from afar to watch us play and the quality of games rivalled English county cricket.”

Pak Crescent used to play at a ground close to the Education Board Office. Zaheer Abbas was in the next street, while Salahuddin ‘Sallu’ and Intikhab Alam also lived close by. National Cricket Club was famous for its fast bowlers while the Rizvia Society Diamond Cricket Club had a spin bowler named Mehmood-ul-Hasan who once clean bowled Hanif Mohammad with a sharp leg spinner after which the Little Master called for a tape measure to see how much the ball had spun. Now living in Houston, Mehmood recounts that moment as the highlight of his cricket career — cut short due to family pressure.

Few neighbourhoods in the world can claim a larger influence on cricket — not even Lahore’s Zaman Park. The Nazimabad XI of 1960s could have competed against international test teams.

Food was a passion and Nazimabadis wanted their old favourites. As Dr Asif Farrukhi observes, “Along with the architecture and intellectual activities even the food reflected the transplanted culture. The sweets and foods of India came here as good or better because the cooks and bakers also moved here. So the nihari in Nazimabad was as good as the one in Delhi and pera made here was better than even in Badayun.”

There were several options for gourmets in Nazimabad. One could go to the original Agha’s Juice Shop for thick mango shakes or Ambala Sweets at Nazimabad Chowrangi for its famous ras gullay and chaat. Mullah Cholay near Rizvia, now in its third generation of owners, was a popular spot as was Wazir Restaurant that used to close only between 3 to 5 am for cleaning and served two anna tea for 22 hours every day, seven days a week. You could discuss Saadi and Firdausi with the patrons dropping by for a hot cup of syrupy tea and get a superb education for a pittance.

Further down towards Chowrangi was Mullah Halwai and also Mullah Restaurant which introduced chicken tikka to Karachi at the princely sum of 1.25 rupees. Café Zaiqa was famous for its nihari but was demolished some years back and replaced with a mosque. If you were feeling plush then it was Al Hasan in Block 1, where, instead of an unkempt boy thumping down a cup, tea was served by a well-dressed steward who would put down the different components with an obsequious whisper.

Today it all seems like a mirage but the Nazimabad of those days was a microcosm of the finest of Delhi and Awadh. However, its role as the epicentre of culture was lost once its residents started moving away in the 1970s. Regarding this phenomenon Ghazi Salahuddin says, “The intellectualisation process of Karachi moved from PIB Colony to Nazimabad to PECHS and slowly dissipated with relocations. At each stage there was some loss but it was most definite when writers, poets, artists, scholars and other people of Nazimabad moved to PECHS and other areas. The de-intellectualisation of Karachi can thus be traced back to when these people started moving away from Nazimabad.”

The Nazimabad of those days may be gone but it lives on in sepia-coloured memories of the thousands of its previous residents who are proud to be part of what was once, arguably, the most culturally-rich locality in the subcontinent.

Sibtain Naqvi is a cultural historian and works in academia.

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, November 20th, 2016