What Pakistan's film industry lost in 1971

THE WAY WE WERE

December 16 marks the 45th anniversary of the secession of the eastern wing of Jinnah’s Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. Much has been written about the traumatic events of the time and the political repercussions of the country being cleaved into two. But the loss of East Pakistan was not just devastating on a psychological, economic or political level. In very real terms, it also affected Pakistan culturally and socially. One of the things lost in the discourse is how the events of 1971 affected Pakistan’s film industry.

In the chaos that reigned on the streets of Dhaka towards the end of the civil war in December 1971, Zahir Raihan’s older brother, the eminent journalist and author Shahidullah Kaiser, had gone missing. He had been rounded up by pro-West Pakistani forces on December 14 along with other intellectuals and his whereabouts were not known. After the Pakistan Army surrendered on December 16 and the nation-state of Bangladesh was declared, Zahir kept looking for him.

In late January, despite the danger, Zahir went searching for his brother to Mirpur on the outskirts of Dhaka. Mirpur was a stronghold of the pro-West Pakistan Bihari community which had fought against the pro-independence forces that Zahir had actively aligned with. Zahir too disappeared.

The setting up of the Film Development Corporation Studios, with modern facilities — including a film processing laboratory — in Dhaka came as a boost to film-makers. From merely five movies in 1963 the number jumped to 16 the following year.

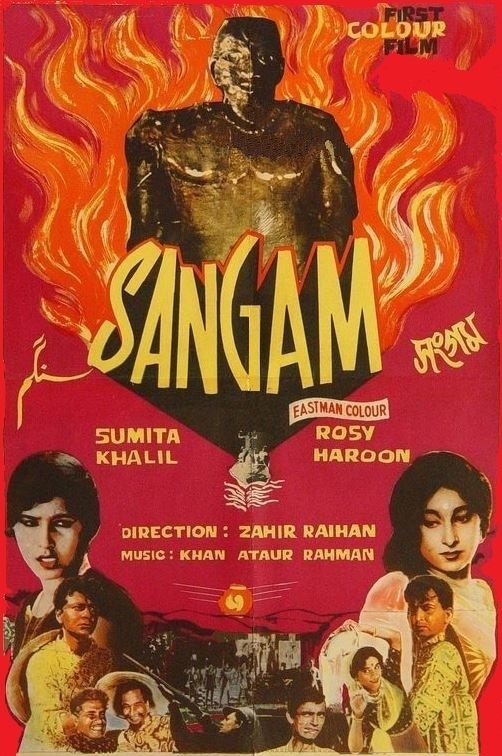

Zahir Raihan had been one of the most promising directors of united Pakistan. A prolific writer and journalist himself, Zahir had cut his teeth in practical filmmaking as the chief assistant director on Jago Hua Savera, the celebrated Urdu-Bengali 1959 film penned by Faiz Ahmed Faiz and directed by A.J. Kardar. Since then he had produced and directed Pakistan’s first colour film Sangam (1964) and Pakistan’s first CinemaScope (widescreen) movie Bahana (1965). He had also directed a number of artistic Bengali films such as Kakhono Asheni (She Never Came, 1961), Shonar Kajol (Golden Eyeliner, 1962) and perhaps most memorably Kanchar Deyal (The Glass Wall, 1963) which had been compared to the films of Bengali Indian auteur Ritwik Ghatak. His disguised political satire against Ayub Khan’s regime Jibon Theke Neya (Taken From Life, 1970) had also been praised by the likes of Satyajit Ray.

The loss of talented film-makers such as Zahir Raihan was only one aspect of the loss that befell the Pakistan film industry with the secession of East Pakistan. Aside from the loss of creative people and skilled technicians, Pakistani cinema was also deprived of a major market and production centre. In 1971 there were 400 cinemas in all of Pakistan and a quarter of them existed in East Pakistan. In 1970, 114 films had been produced in the eastern wing of the country alone, including three in Urdu.

This setback to Pakistan’s film industry has often been mentioned nominally by filmmakers but never really written about in any detail. It would take another decade for the Pakistan film industry to recover somewhat — only to run into another disaster during Gen Ziaul Haq’s martial regime, the effects of which are being felt to this day.

The story of East Pakistan’s influence on Urdu filmmaking is no less riveting.

The year was 1962 and there was nothing much to write home about on the film scene in what was then West Pakistan, except perhaps for the debut of Waheed Murad as a supporting actor in veteran S.M. Yousuf’s film Aulad. On August 3, the first Urdu film from East Pakistan Chanda was released without any fanfare.

Producer Anis Dossani, who had earlier got the East Pakistan-based Ehtesham and Mustafiz to make Bengali films for him, commissioned the brothers to produce the first Urdu film in Dhaka. While Jago Hua Savera and Shaukat Hashmi’s Hamsafar (1960) had earlier been shot in the eastern wing of the country, they were essentially West Pakistani movies.

There were initially no takers for Chanda. Jagdish Anand, the proprietor of Eveready Films (now Eveready Communications), agreed to distribute it in Punjab and the NWFP (now KP) but producer Anis Dossani was left with no choice but to release the movie in cinema halls on ‘commission basis’ in the other territories — comprising Karachi, the rest of Sindh and Baluchistan.

If one is looking for the effectiveness of word-of-mouth publicity, then there can be no better example than Chanda’s. Like the Bengali films from Dhaka, it was aesthetically pleasing. But in addition to the picturesque background, there was also the realistic acting and lilting music. The movie didn’t draw large crowds initially but later went on to celebrate a silver jubilee (25 weeks in the cinemas). Jharna, the Hindu girl who made her debut playing the secondary heroine and would become known as the superstar Shabnam, ended up winning the Nigar Award for Best Supporting Actress, while Subhas Dutta bagged the Best Comedian Award.

A greater success was achieved a year later by the same team’s Talash. The Shabnam-Rahman starrer, studded with fine music by Robin Ghosh, was among only three Pakistani films that stayed in the theatres even after old Indian movies were allowed back into cinemas. It withstood the onslaught for 50 consecutive weeks and celebrated a golden jubilee (50 consecutive weeks on screen).

The setting up of FDC (Film Development Corporation) Studios, with modern facilities — including a film processing laboratory — in Dhaka came as a boost to film-makers. From merely five movies in 1963 the number jumped to 16 the following year. Of these seven were in Urdu, which included Sangam. Naila, West Pakistan’s debut in colour cinema, came only a year later, at the same time that Dhaka produced Zahir Raihan’s widescreen Bahaana as well as the Dossani-Ehtesham-Mustafiz team’s Mala, Pakistan’s first colour widescreen movie.

Scoring the music for Zahir Raihan was Khan Ataur Rehman, a man of many facets. He was a producer, director, screenplay writer, composer and also an actor. Khan Ata, as he was commonly called, made great contributions to Pakistani cinema. Among the extraordinary films that he made were Nawab Sirajuddaulah (1967) and Soye Nadya Jaage Pani (1968), which were released in both Bangla and Urdu. Since Kabori, the heroine of the latter film, could not speak Urdu, he got his friend’s daughter, the singer Najma Niazi — who had also recorded songs in her mellifluous voice for the movie — to dub the leading lady’s dialogues.

Another bilingual movie to be produced in East Pakistan was Shaheed Teetu Mir (1969). But these films were bilingual in a different sense from the earlier Jago Hua Savera, in which the fishermen of East Pakistan spoke in Bengali and the urban population conversed in Urdu. Some thought this was perhaps the main reason behind its failure at the box-office in both the wings of the country because half the movie was not understood by cine-goers of both the wings.

The neo-realistic Jago Hua Savera was based on a short story by Bengali writer Manik Bandhopadhyay with a screenplay by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, who also wrote the lyrics of the songs. They were set to music by the Calcutta-based Timir Baran, known as the father of the Indian symphony orchestra, whose first film score was for P.C. Barua’s Devdas (1935). Baran had earlier also composed music for two Karachi movies — Anokhi and Fankar (both 1956) — including the famous song ‘Gaarri Ko Chalana Babu’. Jago Hua Savera starred Khan Ata and Zurrain Rakhshi from East Pakistan while the the Calcutta-based theatre actor Tripti Mitra played the female lead. Director AJ Kardar, like producer Nauman Taseer, was from Lahore but took on the immensely talented but new-to-film Zahir Raihan from Dhaka as his chief assistant director.

As pointed out earlier, Zahir would go on to forge a stellar career in films. A point worth noting is that while Raihan’s Bengali films fell in the realm of arthouse cinema, his Urdu movies were in the genre of commercial films. It is said that he made Urdu films (read commercial movies) to finance his forays in the realm of artistic Bengali movies.

According to Mushtaq Gazdar’s invaluable book Pakistani Cinema 1947-1997, in all 47 Urdu movies produced in East Pakistan, ranging from Chanda to Jalte Suraj Ke Neeche (also by Zahir Raihan, 1971), were released in the country’s west wing. Making films in Dhaka was a boon for West Pakistani filmmakers because the cost of production was lower there. Rahman, for example, charged a fraction of what Waheed Murad or Mohammad Ali would. The most notable of the Urdu films made in East Pakistan were Chanda, Talash, Bandhan, Milan, Indhan, Sangam, Kajal, Nawab Sirajuddaulah and Chakori.

Talash, the Shabnam-Rahman starrer, studded with fine music by Robin Ghosh, was among only three Pakistani films that stayed in the theatres even after old Indian movies were allowed back into cinemas.

Suroor Barabankvi who had been fortuitously plucked from the offices of the Anjuman-i-Tarraqi-i-Urdu in Dhaka to write the lyrics for Chanda, would go on to write the lyrics for most Urdu films made in Dhaka as well as direct two films himself. One of them, Aakhri Station (1965) was based on a story by the famous Urdu writer Hajra Masroor and was appreciated by viewers with a taste for artistic movies. Shabnam played a mentally challenged woman to perfection. Whenever she was asked why her subsequent performances could not match the standard set by her in Aakhri Station, her patent answer was “Simply because I have never been offered such a challenging role again in my entire career.”

There were exchanges of stars from both wings before the creation of Bangladesh. While almost all of them were in Urdu films, Shamim Ara did play the main character in a Bengali film Misher Kumari (1970) and earlier Zubaida Khanum had recorded a Bengali song for Azan (1961). Nasima Khan, the Bengali actress who played leading roles in both Urdu and Bengali films, produced her movie Geet Kahin Sangeet Kahin (1969) in Lahore where she shared screen honours with popular actor Mohammad Ali.

One more East Pakistani worth mentioning was singer Bashir Ahmed (1939-2014), whose Urdu pronunciation was flawless. He recorded songs in both languages and composed lilting music for some films and occasionally also penned Urdu songs under the pseudonym B.A. Deep. He was from Calcutta (now Kolkata) and was married to a Bengali. He stayed in Dhaka when Bangladesh was created.

The remarkably mellifluous Ferdausi Begum also remained in Dhaka while the composer Muslehuddin, who’d achieved his fame in West Pakistan, settled in London with his West Pakistan wife Naheed Niazi after the country’s split.

Most immigrants from Dhaka to the truncated Pakistan after the creation of Bangladesh, including Naqi Mustafa, the Nigar award-winning screenplay writer for Nawab Sirajuddaulah, could not make it big in what was left of Pakistan.

Producer Anis Dossani, the pioneer of Urdu films in East Pakistan, didn’t do too badly on the other hand. He engaged the well-established director Pervez Malik and together they made such successful movies as Anmol (1973), Pehchan (1975), Talaash (1976) and Gumnam (1983). He did, however, always lament the loss of the empire that he had left behind in Dhaka, which included his family’s shares in two cinemas.

Likewise, director Nazrul Islam (1939-1994), who too was from Calcutta and could speak Urdu only with some difficulty, achieved even greater success in Lahore than he had in Dhaka, where he had already made hits such as Kajal (1965). He moved to Lahore because his wife was Urdu speaking from Uttar Pradesh and she felt insecure in Bangladesh. Nazrul, or Dada as he was widely known within the film-making community, would go on to make some highly successful films such as Ehsaas (1972), Bandish (1980) and Nahin Abhi Nahin (1980) as well as one of the biggest hits ever in the country, Aina (1977) which would play in cinemas for eight years straight. He won Nigar Awards’ Best Director’s trophy three times.

There were, however, two further interesting cases. Nadeem, who got his break as an actor and singer in Dhaka, was originally from Karachi. On the other hand, Bengali-speaking Runa Laila, actually made her debut as a playback singer in Karachi in Hum Dono (1966) while still in school. Her father, a government servant, eventually opted for Bangladesh in 1974. By that time Runa had become a front-ranking singer, winning two Nigar Award trophies for Best Female Playback Singer, once for Commander in 1968 and two years later for her ditty from Anjuman. She later sang for films in Bangladesh and India. The one song she sings invariably and draws huge applause at desi concerts the world over is ‘Shahbaz Qalandar.’

While on singers, one cannot forget Shahnaz Begum, who rendered some lovely national songs and film ditties in the early seventies. She later went back to Dhaka, where she was accused of conspiring against Bangladesh. She has of late become very religious and doesn’t respond to queries about her career as a singer, which seems to be true because this writer made at least two phone calls but met with no success.

Who knows how Pakistan’s film industry might have evolved had the creative forces, diversity and intellectual subtlety of East Pakistan continued to influence Pakistani film-making. It can only be speculated upon. But 45 years on from the trauma of the break-up of Pakistan, it is important to acknowledge that we are culturally poorer because of it. It was not just territory that we lost in 1971.

Click on the tab on top to read about how Ferdausi Begum's voice still haunts music lovers and to revisit some of her songs.

Ferdausi Begum's voice still haunts music lovers

As in other aspects of film-making, Chanda (1962), the first Urdu movie to be produced in what was then East Pakistan, brought a whiff of fresh air. Among the most notable aspects of this change was its music. The songs were largely based on Bengali folk music. The one voice which took the lead over other singers was that of Ferdausi Begum (known as Ferdausi Rahman after her marriage to Rezaur Rahman).

In the years that followed we heard several other singers, such as Anjuman Ara, Shahnaz Begum, Fareeda Yasmin and Sabeena Yasmin, each talented in their own way, but it was Ferdausi who dominated the scene because of her sheer versatility.

After Chanda came Talash, Preet Na Jane Reet, Chakori, Paise, Caravan, Bandhan, Sangam and Mala, to name a few, and Ferdausi excelled in all forms of music from folk tunes like Bhawaya and Bhatiali to ghazals — arguably the most memorable being Suroor Barabankvi’s ‘Ye arzoo jawan jawan’ from Kajal. While on ghazals, no poetry-cum-music buff can forget her rendition of Faiz’s immortal ‘Rang pairahan khushboo’, the cover version of which was recorded a few years later by no less a singer than Iqbal Bano.

Ferdausi once came to Karachi to record a duet, composed by Nisar Bazmi, with a new singer Nazeer Baig for Sehra. But as bad luck would have it, the film never went into production and the song was lost to posterity. She later helped the young singer in getting a couple of singing assignments in Dhaka and, as fate would have it, led him to become an actor of repute in both wings of the country. The man then began to answer to the name of Nadeem.

When PTV began its transmission in Dhaka on December 25, 1964, Ferdausi sang a live number, and from the following day she produced and directed a weekly music programme for kids. Eisha Gauon Shikhi, as the programme was titled, has been a regular TV show for the last 52 years. It inspired the creation of Padma Ki Mauj, which was jointly hosted by singer Nahid Niazi and her Bengali husband Moslehuddin in Lahore until the couple settled down in the UK in 1971.

Ferdausi came to what was left of Pakistan twice with cultural delegations, once sometime in the late 1980s (she doesn’t remember the year), and next in 1991 when she led the group. On both occasions she gave doses of her mellifluous voice. Thanks to YouTube you can have a glimpse of that.

One may like to recall that she did her fellowship from the Trinity College of Music in London in 1963 and in 1965, and when she was merely 24 years old, she was awarded the prestigious Pride of Performance Award.

To say that with the secession of the country’s eastern wing we lost a singer who had enthralled music buffs of West Pakistan for at least seven years is to state the very obvious. —AN.

Click on the tab on top to read about the partnership of Lahore-born singer Nahid Niazi and Dhaka-born composer Moslehuddin.

Best of both worlds: Nahid Niazi and Moslehuddin

Lahore-born singer Nahid Niazi (her real name being Shahida Niazi) and Dhaka-born composer Moslehuddin, who tied the nuptial knot in 1964 were in the UK on a performing tour in 1971 when Pakistan was, to use an expression common in those days, ‘dismembered’.

The two families were highly concerned about their future. Mosleh’s near and dear ones wanted him to return to Dhaka as they thought he would be unsafe in what was left of Pakistan. Meanwhile Nahid’s parents feared that if she were to settle with her husband in the country’s former east wing, she would be highly vulnerable to those seeking revenge, mainly because she also happened to be a close relative of Lt Gen A.K. Niazi, who was the last military commander of East Pakistan.

The best alternative was to stay back in the UK, where they taught music and performed occasionally.

One may like to recall what Nahid’s equally talented singer sister Najma Niazi said about their marriage. When Moslehuddin came to Lahore and scored music for Luqman’s Aadmi, he met his future wife. He went with his proposal to Nahid’s father, the well-known composer, musicologist and broadcaster Sajjad Sarwar Niazi. Nahid’s father said he wanted to meet Mosleh’s, who then flew to meet his son’s father-in-law to be.

Niazi’s father then said he and his immediate family would like to visit Dhaka and meet the rest of Mosleh’s family members. Thus Nahid, her parents and all four of her sisters took a flight to Dhaka. The hospitality offered to them was heart-warming. To cut the story short, the young couple got married in January 1964. The same year in November they had their son Feisal.

Both of them pursued their successful careers. Soon after TV made its debut in Lahore, President Ayub Khan, through Altaf Gauhar, suggested to the PTV chief that a music programme for children be launched with Nahid and Mosleh. The idea was to promote national integration. Thus Padma Ki Mauj, which featured Urdu and Bengali songs, made its successful debut.

In 1969 both of them were decorated with Tamgha-i-Imtiaz for their contribution to music. Those were individual awards, and so were the coveted Pride of Performance awards, which were announced a year later. But sadly they couldn’t get to see the gold medals.

Due to political turmoil, the awards ceremony had to be postponed. When the function eventually took place the couple were abroad. An East Pakistani officer, based in Islamabad, took the gold medals on their behalf but the winners could not see their prizes. Nahid says that the officer was transferred to the country’s eastern wing and gone with him were the prizes.

Nahid and Mosleh settled down in Birmingham with their two children, Feisal and Narmeen. The couple took to teaching music, which is what Nahid continues to do even after the death of her endearing husband 13 years ago. —AN.

Click on the tab on top to read about Shabnam and Robin Ghosh, the 'golden' couple.

The golden couple: Shabnam and Robin Ghosh

Two highly popular and immensely talented East Pakistanis, who stayed behind after the creation of Bangladesh, were actor Shabnam and her husband composer Robin Ghosh.

Shabnam (Jharna in real life) and Robin Ghosh were both Bengalis, but while she was (rather is) a Hindu, Robin was a Baghdad-born Christian. They made their debut around the same time in Bengali movies. When the first Urdu film Chanda was produced in Dhaka, the Ehtesham-Mustafiz team signed the two who had by then tied the nuptial knot. They neither confirmed nor denied the matrimonial alliance. Shabnam played the second lead. Sultana Zaman was the heroine but the younger woman stole the show.

Chanda (1962) proved to be a big hit, if one may use film parlance. The soft, soothing folk music of Bengal, the picturesque beauty of the outdoor locales, and more than anything, the sultry charm of Shabnam, who personified what the Urdu press called ‘Bengal ka jadoo’ (the proverbial magic of Bengal), contributed immeasurably to the movie’s success.

Talash (1963), produced by the same team, was a bigger triumph. It went on to celebrate golden jubilee, paving the way for many Urdu films produced in the country’s east wing.

Robin had a chequered career initially, but Shabnam continued to go from strength to strength.

In 1967 came the record-breaking flick Chakori, which is remembered today for the new male lead player Nadeem (Nazeer Baig) as also for the scintillating songs scored by Robin Ghosh, who got his second Nigar Award trophy for best music (the first was for Talash).

The husband-wife team came to Karachi, which they found to their greater liking than Lahore. They bought a house in the PECHS area. Shabnam’s first assignment was Eastern Film Studios’ multi-starrer Ladla, but the movie hardly created ripples at the box-office.

Also read: 10 timeless Robin Ghosh tracks that will take his fans down memory lane

Producer-director Pervez Malik’s Jahan Tum Wahan Hum was the US-trained film-maker’s first flop. He had directed super successes like Heera aur Patthar and Armaan, a few years earlier. Robin’s fine compositions didn’t reach the masses. Shabnam, however, remained in great demand both in Karachi and Lahore. Robin’s career would have taken off but he spent most of his time escorting his star wife. Shabnam remained among the top heroines and she also acted in a few Punjabi films when they came in vogue. She found it easier to speak in Punjabi than in Urdu when she made her debut in Chanda. It was because Urdu was not widely spoken in Dhaka but, on the other hand, Punjabi was the lingua franca of Lahore, where she spent most of her time.

Robin’s career blossomed from 1972 onwards when he recorded some memorable ditties for such movies as Ehsas, Chahat, Sharafat, Do Saathi, Jio Aur Jeene Do, Amber, Dooriyan and the box-office bombshell Nazrul Islam’s Aina. Then came the lean period, from 1988 to 1995 when his name appeared on screen only three times.

A tragedy occurred when sometime in 1995 Shabnam suffered a stroke, from which she ultimately recovered. In 1999 she and her spouse moved back to Bangladesh, where they had large families to support them, carrying with them a number of awards and medals.

In Dhaka Robin officially retired but would occasionally work with musical programmes on TV. As for Shabnam she did what are called ‘character roles’, the most successful of which was Mummy, the title role which won her kudos. About five years ago, they paid a visit to what was once West Pakistan and were warmly received.

Robin unluckily died in February 2016. Shabnam is alive and still resides in Bangladesh. According to a close friend in Dhaka, in her old age, few things please Shabnam more than recalling the fruitful years she and her husband spent in Karachi and Lahore. —AN.

Click on the tab on top to read about what made music different in the country’s two wings.

What made music different in the country’s two wings

It is a well-known fact that music happens to be an integral part of almost every household in Bengal, irrespective of caste or creed. One can hear the keynotes of folk songs like ‘baul’ ‘bhatiali’ and ‘bhavaiya’ reverberating all over the rural areas (particularly across rivers) and songs based on Rabindra Sangeet and Nazrul Geeti being sung in the cities.

The situation was no different in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The release in 1956 of Mukh-o-Mukhush, the first Bengali feature film produced in Dhaka the provincial capital, ushered in the era of Bengali film music in East Pakistan. The movie paved the way for regular production of Bengali films. However the tunes composed by well-known music directors remained confined to East Pakistan because of the language barrier between the two wings of the country.

With the beginning of production of Urdu films in Dhaka and their release in West Pakistan in the 1960s, the music lovers in this part of the country were introduced to different kind of melodies composed by Robin Ghosh, Khan Ata-ur-Rehman, Subal Das, Ali Husain, Karim Shahabuddin, singer-turned-composer Bashir Ahmed and others. The journey began with Chanda in 1962 and continued till Jalte Sooraj Ke Neeche, the last Urdu film produced in Dhaka and released on September 10, 1971.

The commercial as well as musical success of many of these films helped popularise the till then unknown singers such as Bashir Ahmed and — despite their less-than-perfect Urdu pronunciation — Ferdausi Begum, Anjuman Ara, Farida Yasmin and Sabina Yasmin.

Film songs, recorded in both Lahore and Karachi, were already the most popular genre in West Pakistan. Based on Punjabi folk and/or North Indian classical music these songs were often quite heavily orchestrated and rendered in high pitched voices. In comparison the simple, soft and Bengali folk-based Urdu songs recorded in the Eastern wing of the country were like a breath of fresh air and were lapped up by listeners in this part of the country. In spite, or maybe because, of their light (and at times wanting) orchestration, these songs were soothing and didn’t put the listeners’ ear drums to the test.

Moslehuddin and Deebo Bhattacharya were the two Bengali composers who began their careers in West Pakistan in the 1950s and composed some lilting as well as popular songs. However, it was Ghosh who really made a name for himself through his western-oriented tunes blended with soft Bengali compositions such as the ones he recorded for Chakori, Ehsaas, Aaina, Bandish, Chaahat and so many others.

Another unique aspect of some of the songs composed by Ghosh was the usage of choir singing which later became a hallmark of his compositions. Barring Khwaja Khurshid Anwar, no other composer in West Pakistan could make such an excellent use of choir. It may be mentioned here that Ghosh being a Christian had taken part in choir singing in the church from his childhood. He later took formal training with composer Salil Chawdhury’s choir group at Calcutta (now Kolkata).

While drawing a parallel between the film music of the two regions of Pakistan, one can say that the music composed in West Pakistan had more variety — there used to be different types of songs in a single movie such as classical, garnished by intricate murkis and taans, Punjabi folk and cabaret. Moreover the songs were supported or at times over-weighed by heavy orchestration. The playback voices used here were mostly trained in classical music and possessed enviable range.

In comparison, the tunes composed in East Pakistan were simple, almost devoid of intricacies (barring a few compositions of Ata-ur-Rehman’s for Nawab Sirajuddaulah and by Subal Das for Kajal and Indhan), heavily influenced by Bangla folk music and generally easy on the lips.

The voices one heard in East Pakistani songs were rather subdued and middle-aged as compared to their counterparts in West Pakistan who tended to (or were made to) sing in the third octave, sometimes due to the demands of a situation and many times out of habit.