Campus diaries: Forbidden friendships in Pakistan’s universities

With girls huddled at the back and boys at the front, a chemistry lab class is in full swing at Lahore’s historic Punjab University (PU) - ranked second in Pakistan.

For Urooj, a science student at PU, this kind of segregation is quite common. “As long as we can hear the lab attendant’s voice, we have to stand at the back of the class,” she says.

The kind of gender segregation Urooj is referring to extends well beyond her classroom. She reveals; “Even outside the classrooms there are different spaces for girls and boys. There are a number of canteens where girls aren’t allowed. In the ones they are, curtains are drawn to separate them from the boys."

According to the 2015 fact book of Punjab University there are only two percent more boys than girls studying at the institution. With the population evenly divided, segregation on logistical grounds is a flimsy argument.

Rather, it appears to be a moralistic pursuit based on one of Pakistan’s widely accepted and deeply problematic social constructs: the belief that girls and boys mingling and interacting leads to immorality, and the disintegration of society.

Systemic moral policing and gender segregation seem to have become a norm at university campuses, manifesting a kind of intolerance that is deeply uncharacteristic of a progressive academic culture.

A sense of resignation in Urooj’s voice reflects that there are in fact a number of layers to the on-campus gender politics that influence her university experience.

Late in October 2016, a group of agitated, club-wielding students marched through a part of the campus. They were looking for a boy who they had found sitting with a girl in the vicinity of PU's sociology department.

“Some of them stormed the building, broke the gate and tortured the guard. They slammed doors and shattered the windows. All this hooliganism lasted more than an hour or two,” narrates Hanain Afridi, a student who witnessed the events that took place at the college’s Institute of Communication Studies (ICS).

These student activists were believed to be part of the Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba (IJT), a right wing student organisation that acts as the unofficial student wing of the Jamat-e-Islami. Elements of the IJT are notorious, students say, for using aggression to assert power.

Today, it seems that the IJT is behind much of the moral policing that happens in one of Pakistan’s largest public universities. How do they command such a position of authority? Some say the IJT owes its success to the consistency and organisational ability it has embodied over the years. Others feel that factions of the university administration are complicit in nurturing and facilitating the organisation.

Urooj feels that the administration, in turning a blind eye towards such incidents, stands complicit in aiding violent elements.

On some occasions, she says, students do resist forcefulness of student organisations but the administration remains silent; “It seems that the administration is also following an unwritten agenda of moral policing.”

When asked how the organisation justifies its stance on gender segregation, a representative of the IJT Furqan Khalil says they have always protested against co-education in Pakistan. “We demand that the government should establish separate educational institutions for boys and girls,” he said.

“Local culture demands that young girls and boys should not sit as couples. We never discourage girls and boys in groups,” said Furqan.

To strengthen his argument, Khalil reveals that there are departments in the university where faculty heads too, restrict girls and boys from sitting together. He added there are other departments, where such restrictions do not apply.

While PU has its segregation ‘code’ controlled by the activities of the IJT, in other universities, the administration ensures ‘morality’ on campus.

Gender segregation is enforced through codes of conduct, policies, notices and fines. The ‘codes of conduct’, usually found on an institution’s website, vary greatly from explicit to ambiguous rules leaning towards the bizarre.

Case in point: at one of Comsats university’s colleges, the university seeks to implement a rule barring, “Entering entryway [sic] of opposite sex on campus or allowing the same,” leaving much room for imaginative interpretation.

Muhammad, a student at Comsats’ Abbottabad campus feels that the regulations are merely lip service.

“We don’t have many restrictions but couples are fined if they’re found sitting together. The fine is Rs5,000 for both individuals,” he said. Not quite concerned about the restrictions, he added; “people in Punjab have a relatively freer mind, but here in Abbottabad, boys and girls don't interact that much anyway.”

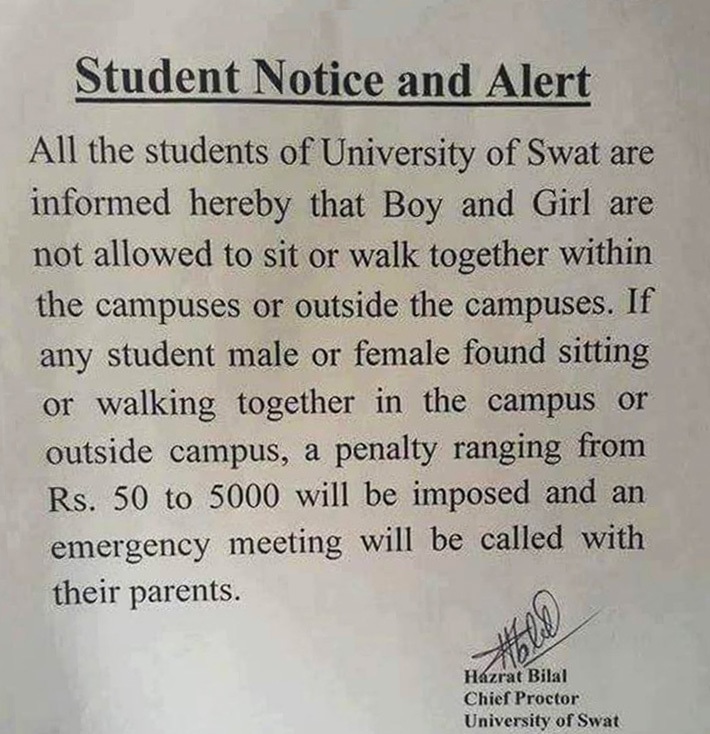

Similarly, at the University of Swat, a fine applies to boys and girls found sitting or walking with each other. Earlier in March 2016, the university announced “a fine of between Rs50 to Rs5,000 on any two people of the opposite sex found sitting or walking together.” The notification barred boys and girls from sitting or walking even “outside the campuses”. It further stated that as a consequence, an “emergency” meeting would be called with the student’s parents.

The National University of Science and Technology (NUST) presents a regulation in its policy and procedures document that encapsulates a profoundly ambiguous moral compass.

Nust, the document states, is against; “Indecent behaviour exhibited at the campus including classes, cafeteria, laboratories etc, defying the norms of decency, morality and religious/cultural/social values by a single or group of students.”

The moral settlement embedded within Nust's ‘code’ falls squarely in the realm of non-falsifiable, fluid and arbitrary notions of morality. To that degree, it casts a wider net on unsuspecting students who could at any point, find themselves in trouble over having violated the university’s norms of decency, morality or religion.

Nust’s website also states; “Undue intimacy and unacceptable proximity, openly or in isolated areas will not be tolerated. The tendency of taking advantage of common places like cafeteria and shops is objectionable and undesirable. Also, students are advised to avoid movement in mix groups [sic] in the campus after sunset.”

Nust's student, Sara Ansari argues that such rules are rarely implemented but when they are, it is done arbitrarily. “For example, girls and boys are not allowed to play football together but they can play squash and table tennis. Similarly, while the rules for both genders are the same, girls bear the brunt of these restrictions. If a boy is caught smoking on campus they are given a warning but if a girl is smoking, she is reported to the department and official action is taken,” she explained.

Ironically, while zeroing in on policing heteronormative behaviour, much of the systemic moral policing at Pakistani universities illustrates a blindness to the more transient shades of gender.

It's a Wednesday afternoon at the Quaid-e-Azam University (QAU) Campus in Islamabad and classes for the day have just finished. Students stream in and out of the building in small groups, chatting amongst themselves. Some even sit as couples enjoying the winter sun and the vistas of the Margalla Hills that the campus offers.

This is seem as problematic by some students. Sheroon, a student of linguistics at the QAU, feels that the university should play a more active role in imposing certain rules over the interaction between men and women.

"Once a couple were kissing on campus and when the students complained, no action was taking by their department. When students see such behaviour on campus, it causes moral confusion, they no longer know what's right," he complains.

Director of the Centre of Excellence in Gender Studies, Farzana Bari has been affiliated with the university since the early eighties when she was a student. The culture of the university, she says, has changed a lot over the years, becoming more and more conservative. "Back then there was free mixing between students and girls and boys treated one another as friends. Nowadays, many women choose to hang around in women-only groups," says Bari.

She has, in the past, received complaints regarding teachers who attempt to police students on morals, expressing displeasure over their 'frankness with one another'. The university, however, does not have official policies or rules regarding either the interaction between men and women on campus.

At QAU, gender separation seems largely self-imposed. Bari argues; “Such voluntary forms of segregation are detrimental for larger society because students are then ill-prepared for workplace interactions.”

For now, a murky set of moral 'codes' are going to stay in place for the foreseeable future. Until more tolerant guidelines built from socially progressive values are introduced, students who wish to have friends outside their own gender may need to keep a spare Rs5,000 note in their pocket to pay the impending fine.

Do you have an interesting story about university life? Share it with us at features@dawn.com