Back in the 1980s, Alamgir and the Benjamin Sisters sung the iconic patriotic song Khayal Rakhna which was a directive to the youth to take care of things. Today, some three decades on, the trio have all migrated from Pakistan and Alamgir has been running from pillar to post in Canada, trying to collect money for his medical treatment. A music icon of the past lives in abject helplessness today — such has been the curse of being a professional musician in Pakistan.

But this time round, it is Pakistan’s music industry itself that is facing its worst crisis. Today, major record labels exist in name alone, album sales have dried up, the infrastructure to support music distribution has crumbled in the face of technological changes, television exposure for music has dwindled despite the overarching popularity of avenues such as Coke Studio, and public concerts — which have often been the bread and butter of the country’s musicians — are few and far between. Add to that the ever-present dilemma of piracy which deprives artists of making a living from their creative efforts. In this atmosphere of gloom, the question most struggling musicians are asking themselves is whether there is a future for them. Will the vibrancy of Pakistan’s music scene of yore become just a faded memory?

The economics of producing music

For any artist, music production is no longer a straightforward process. First, there is the creative process — experimenting with lyrics, melody, instruments and the like. This is followed by countless hours of practice and perfecting the routine. Then comes the recording — artists tend to approach record labels or prospective investors to help them with studio space, equipment and production expertise.

Pakistan’s music industry is facing an existential crisis today...

Once the recording and post-production process is complete, the issue of marketing and distribution rears its head. In the past, this was often handled by the recording companies which stocked the albums at stores and also often handled the publicity angle, funding videos that would air on dedicated music channels eager for new content. They had also made some headway in ensuring that at least their content was not pirated in the major metropolitan areas. Eventually this marketing would translate not only into greater sales — though musicians would get a raw deal even then — but lead to bookings for concerts which is where musicians actually earned, from ticket sales and sponsorships.

All of that has now changed. With big-name recording companies such as EMI, Fire Records and Sonic now dormant or out of business altogether, musicians often must pony up the expenses for their recordings — which can be as substantial as up to a million rupees — and still not have the resources to stock their product at music stores or to combat piracy. Album sales have virtually disappeared with the advent of digital distribution which is far more geared towards the release of singles. Cassette tapes, which were the cheap staple of long-haul truckers and which led to the viral popularity of many once-obscure musicians such as Ataullah Essakhelvi, have become outdated. And the four main TV channels that were dedicated to music have folded. Thanks to security fears and excessive taxation, public concerts have also dried up. ‘Security concerns’ have pushed music indoors back into smaller performance areas — the same venues they may have hired as college bands.

While the creative suffocation of the 1980s no longer persists, the current freedom for musicians has an ironic paradox. Musicians can make whatever kind of music they want, but very few people are listening and even fewer paying for the privilege.

The past is another country

Back in the 1990s, as Pakistan was emerging out of the suffocation of General Ziaul Haq’s dictatorship, music received a boost as both the state-run Pakistan Television (PTV) and the privately-run channel NTM ran separate music shows to promote local pop music. That was the time when Junoon, Awaz, Hadiqa Kiani, Shehzad Roy and others were entering the scene as newbies. They’d create songs, send them in to the music shows such as Music Channel Charts (PTV) or VJ (NTM), get noticed, and sign up with a record label to produce an album. These artists would subsequently release their albums on cassettes and later, on CDs too.

But even before Junoon and Awaz, the sound of Ataullah Essakhelvi was reverberating in buses and wagons across Pakistan. Essakhelvi was the original trailblazer of releasing cassettes in Pakistan and bypassing the ‘music establishment’ to produce affordable music. He was given a cold shoulder by PTV as his music was not deemed highbrow enough but he began producing and releasing music on his own.

At the time, TV, film and radio were deemed to be the gatekeepers of music — music had to be a certain way to find acceptability. But Essakhelvi changed the trend. He employed the tape recorder revolution to herald a cassette revolution in Pakistan. “He became a sensation in the 1980s well before anyone heard him on television, film or radio. And that, back then, was unheard of,” writes Dr Adil Najam on his blog Pakistaniat.

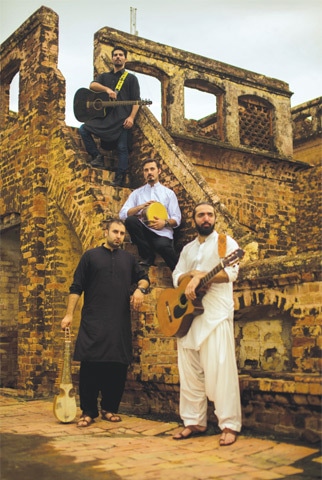

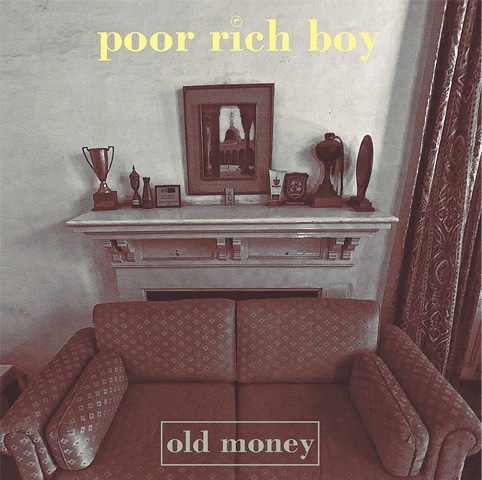

The past, though, is another musical note. While record labels around the world have adapted to newer digital online medium of distributing music, in Pakistan, they haven’t or refuse to do so. More and more artists are now self-publishing or willing to give their music out for free. There are some that have exclusively built their careers through their presence on the internet — Ali Gul Pir, Khumariyaan and Poor Rich Boy come to mind — before being picked up by TV channels. In part this is because the record labels don’t really exist anymore when it comes to producing music.

“I think the last time record labels were relevant in Pakistan was probably the early 2000s when Fire Records was around,” says Ahmer Naqvi of the online platform, Patari. “Record labels’ relevance, in a traditional sense — where the record label is scouting artists and giving them albums and releasing their music and promoting it — has not happened since probably the late 1980s or the 1990s. Even then you had very few bands that

were signed to them. Prior to that when the film industry was around, and there were a lot of (folk) artists [that would record for films], record labels were really, really big in Pakistan.”

Lapse of the labels

But as the world changed around them, record labels stood still.

“There weren’t many issues when we started,” says Dr Akbar Yezdani, the former chief operating officer (COO) of Fire Records, a label that stirred quite a bit of controversy in the industry but also had the largest repertoire of modern big-name artists in the country. “I’m talking about 2006-2007. CDs and cassettes were still being sold. The ratio of sale of cassettes to CDs was 1:3 — for every one cassette, three CDs were being sold. Within three years of that time, cassettes and CDs went on par and then cassette sales started to dwindle before completely grinding to a halt.”

Around that time, says the former Fire Records chief, there was still a trend of artists performing in concerts. “I remember all these artists used to perform a lot. They were constantly shuttling between Karachi and Lahore. I remember Jawad doing four to five gigs a night,” he claims. “I remember attending a gig every weekend. That means on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays, there were at least four or five concerts happening across the country every night.”

At the time, there were also at least four dedicated music channels — MTV Pakistan (formerly Indus Music), ARY’s The Musik, Geo’s Aag and Aaj’s Play — which showcased Pakistani music.

“All of a sudden, a new channel came up. It was called G Kaboom. It began airing 100 percent Indian content and its rating just shot through the roof,” explains Dr Yezdani. “It took over the whole music scene [on TV]. All of a sudden, people dumped all other channels. Even MTV took a hit, which was part of the same network.

“When G Kaboom came, people saw that Indian music sells like nobody’s business. G Kaboom was doing around one crore rupees business a month. And their expense was very minimal. They just needed a small server and the minor cost of up-linking content. They were just pirating music and airing it, there was no licensing, nothing. The rest of the channels woke up to this new reality and started doing the same. That’s when things started to change.”

Meanwhile, in the rest of the world, as music started going online, artists began to make money off downloads. iTunes, for example, began charging 99 cents on each track downloaded. This option seemed to evade Pakistani artists, till recently, when various online music streaming platforms emerged.

Dr Yezdani’s independent label, which represents one of the biggest portfolios of Pakistani artists and albums, is signed up with the international music streaming mobile application, Saavn. He hints that he made the move to digital after witnessing music platforms switching from physical forms (cassettes and CDs) to purely online hosting/streaming.

“[The switch happened] roughly three years ago,” says Dr Yezdani, “And the switch happened very, very quickly. You have to understand that from one physical format to the next, change is very difficult. But the switch from physical to digital is not very difficult.”

Labels such as EMI, which has been around since 1948, were hit badly. From a record label that once boasted Noor Jehan, Mehdi Hassan, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Ghulam Ali, Iqbal Bano and Farida Khanum among others on their roster, EMI’s role in the industry seems to have changed.

“We are primarily working on the implementation of copyrights,” explains Zeeshan Chaudhry, general manager of EMI, “because otherwise, our music business model will not be able to survive. Piracy isn’t just when you copy our songs into another CD — those are hardly being used now. Piracy is when you use a song without license and permission. On TV, when they play music in the background without any proper permission or due — that is piracy.”

“We are facing challenges on a different level. If we release anything, TV channels are not willing to run our videos because they want to use that as an arm-twisting measure against us since we’re asking for royalties,” Chaudhry continues. “Similar is the case with radio stations. To this day, 8XM is violating Pemra regulations by playing foreign music. They do play a little Pakistani music but they’re also asking for Rs20,000 per airing of any video.”

The digital medium is akin to a rip tide that can wash away even a good song into the shadows. “About 99 percent of artists on digital platforms remain obscure,” says Dr Yezdani, “You’ve made a product but it is now lying at the back shelf of the store. You don’t even know it exists.”

“Copyright is one area that is least understood by our legal system,” says Dr Yezdani, “Aap kay enforcers hi trained nahin hain [your enforcers are not trained] in what is ‘copyright’ and how to tackle it.”

But it’s not just the authorities, according to Naqvi, it’s also the artists that are unaware. “Most Pakistani artists are not aware of the copyright law,” he says. “Expecting Pakistani artists to know how an industry works when there is no industry is asking too much.”

EMI has almost 60,000 tracks in their archives, out of which they claim to have digitised about 20,000. “This is an ongoing process. Aur distribute bhi kar rahey hain [And we are also distributing]. Whenever you release any album or track with us, it releases worldwide over 800 online stores,” claims Chaudhry.

For Naqvi, though, EMI has altered its traditional function as a record label — to discover and to patronise music talent and help them launch a career. While labels used to be the primary avenue for hunting and promoting talent, many musicians were left frustrated by their machinations and control of content. A promising band from the northern part of the country, for example, chose to go with a big-name record label for their debut album. This was also the label’s big comeback. But that excitement soon turned into frustration. Even months after their album had been launched, it wasn’t available to listeners across the country.

“The situation is so bad right now,” said one of the band members back then, “that they’re actually couriering the CDs to local shops here.” Their album was later pirated and released for free online. Completely disillusioned by the treatment meted out to them by the record label and their lack of professionalism, the band decided to put their second album out on the internet for free. “Why sign your music off to a corporate entity when it’s not actually doing anything for you?” they argued.

In another case, a band was left upset with a record label company for not releasing their album on time. Months of hard work had gone in by the band, there was constant speculation in the media about their upcoming album, but the label did not cash in on the hype being generated.

“Things just got delayed,” says one of the band members with a hint of frustration in his voice. “We’d call the executives at the label and they’d assure us that they were going to release it soon, but it would constantly get delayed. To the point that it took well over a year after the album was complete for them to release it.”

But by then the buzz had died down, the band had broken up, and audiences had moved on. The career of what was once one of the most promising new bands simply crashed. It wasn’t the music. It was just really bad timing. And like a lot of artists around that time, they blamed their record label for their fall.

The digital rip tide

But do the traditional media and big-name record labels even matter anymore?

The trend of the last few years is that more and more artists are now forgoing physical distribution in favour of digital. Of the options available to them, three platforms stand out: GanaHungama, Saavn and our very own Patari. The first is based in India, the second in the United States and third in Pakistan. Where the first two host artists from around the world, the latter focuses solely on Pakistani music.

All of Dr Yezdani’s clients are found on Saavn where, as he argues, they are in the company of international stars. But the digital medium is akin to a rip tide that can wash away even a good song into the shadows. For a medium that is open to all, there are hundreds of aspiring artists from Pakistan, who have put their music online. On bigger platforms they’re competing with hundreds of thousands of other artists from around the world, not just for space, but for attention.

“About 99 percent of artists on digital platforms remain obscure,” says Dr Yezdani, “You’ve made a product but it is now lying at the back shelf of the store. You don’t even know it exists.”

Perhaps this compelled some bands and artists, including well known ones such as Noori, to turn to Patari, where their audience is largely Pakistani and the commercial traction they find is also Pakistani. Patari’s business model operates on a per-click basis: the more times a song is listened to, the more is the royalty earned by an artist.

But for Naqvi, it’s not just the volume but the quality of content that is being put out there that is contributing to this. “I think definitely right now the problem is that music doesn’t have the same cultural cache as it used to,” he says. “There is a way of breaking out,” he continues, “but it requires certain approaches which we don’t see from the artists and often there is no one else really to work with that. I would refer to the Patari Tabeer series where artists that came out not only were very obscure but also the lacked the financial or social resources to break through.”

And yet they did. For Naqvi, their success boils down to the ‘presentation’ of their music. “It’s really important how you package and promote your music online,” he says. “There is so much noise these days — from the internet, other channels and all sorts of entertainment options that didn’t exist 10 years ago. You have to be smart about this.”

But even if they do all the right things and their music goes viral online, what is the endgame? “The only sort of endgame for Pakistani artists is that you come on Coke Studio,” claims Naqvi. “But going from SoundCloud or Patari to Coke Studio is a massive leap.”

When YouTube first entered Pakistan, there was the impression that Pakistani artists will now finally be able to make money off their content hosted on that platform. “First of all, YouTube was a huge platform in Pakistan,” says Naqvi. “Then it got banned for five years and consumer behaviour changed. Pakistan is one of the few places in the world where Facebook is the premiere video platform.” And Facebook doesn’t pay for your content. In fact, the artist ends up paying Facebook to promote it.

This begs the question: are Pakistani artists making money from digital content?

“I don’t think they are,” argues Dr Yezdani about those that are hosted on more ‘international’ platforms such as YouTube, GanaHungama, Saavn etc. “They’re struggling to be noticed.”

In financial terms, things look more positive for artists hosting content on local platforms. “Last December, we paid out royalties worth 1.25 million rupees,” says Naqvi. “That’s a process we will be continuing.”

Not all artists are created equal, though, even online. The dynamics of who is the bigger star online seems to be as it has been offline. “Of the payouts that we did,” says Naqvi, “The major beneficiaries were Strings and Noori — the really big bands. The smaller ones are not going to be making enough money at this moment to sustain themselves purely on that.”

“We are the third-most listened-to act on Patari after Atif and Noori,” says Sparley Rawail from Khumariyaan. “Even then we need live music concerts [and a part time job] to earn. Right now, I am writing to you from my office, I have a day job and so do the other boys,” says Rawail. “But if you put in the effort and have a sound that people like, then between royalties, live shows and opening a studio and producing, one can make a decent living. [Having said that,] one has to know their craft very well and is willing to jump to the production side to become successful.”

The bit about the primacy of concerts is echoed by Naqvi. “Streaming your music online is a revenue option, but the bigger option has always — and certainly now — is live performances,” he says. “And that’s something that’s not easy to do in Pakistan: taxes are high, the security situation is often insecure, and there are not enough venues.”

Does that automatically mean that there is no money in music? Not quite.

“Corporate capture of music is huge. We calculated recently that 50 million dollars were spent by just four brands on music last year. That’s an insane amount of money in an economy such as ours,” says Naqvi. “Yet each of those shows had the same faces, similar sounds. By and large very few of them are committed to creating newer stars or finding new people or knowing what to do with them.”

Coke Studio is often cited by the average listener as a great promoter of Pakistani music with excellent production values. But the question to ask is how many musicians actually make it to its select roster. The ones who have really benefited from its worldwide fame are the already established acts. And for every previously lesser known artist such as Asrar or Momina Mustehsan that it has featured, there are hundreds who will never get the chance to have their musical talent judged.

Meanwhile, for the thousands of Pakistani artists trying to eke a living, they find themselves as fodder for the industry’s experiments with production and payments. While we pledge Khayal Rakhna for our country, sadly the same does not apply for our musicians.

The writer is a member of staff.

She tweets @MadeehaSyed

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, February 12th, 2017