THE quality of villainy in our land has acquired sinister overtones. The recent cry of anguish in this regard by a provincial police chief is the collective voice of the forces of law and order. As his course commander in 1989, I am proud of my under-training assistant superintendent, now the inspector general of Sindh Police, to have spoken the truth and conveyed a loud and clear message to the powers that be, in highlighting the vendetta killings of police officers who bravely carried out an operation against the militants of a political dispensation in the 1990s.

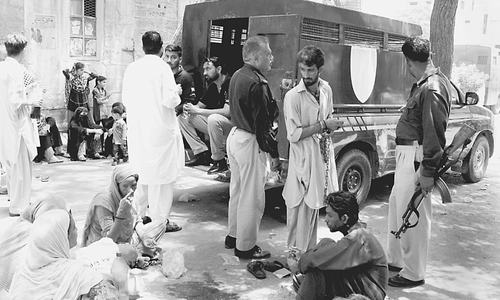

One cannot forget the betrayal of the then rulers and policymakers who abandoned the fearless warriors to the vicious militants that went on a rampage, unhindered and emboldened by complicit political power-seekers. That sordid saga will forever remain etched in the institutional memory of the Karachi police. IG Khawaja reiterated the sentiments of the force and said the Sindh police was quite capable of restoring peace and order provided that the political will was there to support it in its endeavours.

The lack of political will to reform the police was reflected in the IG’s second observation. In 2011, the PPP-led Sindh government repealed a modern police law promulgated in 2002 and replaced it with an archaic colonial constabulary model of policing. That was the most retrogressive step taken to reverse the process of police reform. Balochistan soon followed suit and introduced legislation that was a carbon copy of the Police Act 1861. A blatant attempt to reintroduce the executive magistracy was, however, struck down by the Balochistan High Court.

Where is the political will to reform the police into a modern, independent institution?

In the words of Aristotle, “law is a form of order; and good law must necessarily mean good order”. In this context, the Police Order 2002 is a law “in sync with the spirit of the times”. It contains five basic features under which the police “has an obligation and duty to function according to the Constitution, law, and democratic aspirations of the people”. First, and the foremost objective, is to depoliticise the police through institutional safeguards in the form of public safety commissions at national, provincial and district levels in order to ensure democratic rather than political or bureaucratic control over the police, hitherto exercised for far too long, resulting in politicised and partisan police services all over the country.

The second feature of modern law is to make police a highly accountable institution by establishing independent police complaints authorities at the federal and provincial levels. This external oversight mechanism is meant to ensure impartial accountability of the police, which has become notorious for corruption, misuse of authority, torture, illegal detentions, improper investigations and lack of sensitivity to the citizens’ needs.

The third feature is to grant police departments operational and administrative autonomy in order to avoid undue interference and use of extraneous influences in its work by recognising that the provincial police chief’s powers are those of an ex-officio secretary to the government, meaning he has administrative and financial autonomy as the head of the department. Moreover, the law provides security of tenure to senior police officials at provincial, regional, city and district levels. This crucial provision to ensure administrative stability and autonomy has been violated with impunity by the chief executives of the federal and provincial governments. A recent example was the unjustified attempt to send the IG Sindh on ‘forced’ leave, which was resisted by civil society, media and the higher judiciary. This is a welcome development that may hopefully lead to the beginning of an end to use of arbitrary authority to transfer heads of police on whimsical or capricious grounds.

The fourth basic feature recognises police as an instrument of law and accountable to the judiciary for carrying out fair and impartial investigations. The modern concept of functional specialisation has been introduced in the law to ensure a high degree of professionalism in the investigative processes and reliance on scientific methods to achieve convictions in court.

This also entails specialised investigative cadres that work closely with prosecutors in order to meet the ends of justice through due process and observance of human rights. Sir John Fielding lamented in 1768 that “the police of an arbitrary government differs from that used in a Republic” and “it must always be agreeable to the just notions of the liberty of the subjects, as well as to the laws and constitution of the country”. This 18th-century dilemma in England haunts our Islamic Republic even in the 21st century.

The final feature of the police law of 2002 is the need for the police to be a community service instead of being perceived as the coercive arm of the state. Police is a public service and the Constitution and law are its real masters. Its responsibilities and duties are spelt out in the law, and violation entails disciplinary action and criminal prosecution in case of wilful negligence. For far too long, our police have followed Charles Napier’s military model of the Irish Constabulary and ignored “the democratic aspirations of the people”.

The above five features constitute the basic architecture of the Police Order 2002. It is a pity that the federal government never made an attempt to promulgate this law in the Islamabad Capital Territory. The National Internal Security Policy announced in 2014 cannot be implemented without establishing the National Public Safety Commission or independent police complaints authorities through the National Police Bureau.

While Sindh and Balochistan have reverted to the 19th-century colonial models, the Punjab government too has paid lip service to the modern police law. It has established neither the Provincial Public Safety Commission nor an independent Police Complaints Authority, which is required to carry out accountability of the police under either a retired judge of the Supreme Court or a retired IG police of impeccable repute selected by the chief minister and notified by the governor along with six members of unblemished credentials selected by the public service commission for a period of three years.

Indeed, as correctly summed up in an editorial in this paper, “bitter pills need to be swallowed in order to reform” the police as “a responsive and modern” institution. Who will rid us of this state of amnesia?

The writer is a retired police officer.

Published in Dawn, February 18th, 2017