Given the smallest chance, some people can spend hours talking about themselves. Aziz Fatima is not one of those people. She is the granddaughter of Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar, one of the most significant men in Pakistan’s history, but even that does not imbue her with the slightest bit of self-importance, and her conversation is filled with stories of everyone and everything but herself.

Illustrious parentage notwithstanding, she was a famous baby in her own right. There is a video of her aged around six months, when she accompanied her parents and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to the United Kingdom for the Second Roundtable Conference in 1931 on the ship SS Rajputana. It was a meeting Gandhi did not want to attend and his displeasure was evident. When the photographers covering the journey realised that Gandhi smiled only when in the company of the infant belonging to Congress member Shuaib Qureshi (who was also editor of Gandhi’s newspapers Young India and New Era) and his wife Gulnar, “they asked my father if they could borrow me,” says Aziz Fatima. “The pair of us was called the ‘toothless grins’ since neither of us had any teeth!”

The baby with the toothless grin celebrated her 86th birthday this year. Born on Feb 23, 1931, in Bhopal, India, she takes obvious enjoyment in telling the story of how her parents met. “My father and his friends were deeply involved in the freedom movement, and vowed never to get married in order to be able to devote all their energies to the cause. One day, however, Baba came to my grandfather’s house for a meeting. My mother was watching from upstairs. She held a rose in her hand, which fell towards him. He looked up at the beautiful young woman and they were soon married. She was 18, he was 40; it was a very large difference in age, but there was great love between them.”

Aziz Fatima, Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar’s granddaughter, is a treasure-trove of fascinating stories

The eldest of seven sisters and one brother, Aziz Fatima was educated at the Cambridge School in Bhopal, and in 1946 sat for her matriculation exams from the Ajmer board. “We were educated mostly in English,” she says, “but when Khaliq Chacha (Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman) visited we would engage in baet baazi, which was how we learned Urdu poetry.”

In 1948 the family left Bhopal for Karachi. Living arrangements were a ‘flat’ in the Urdu College, consisting of two classrooms with another small room between them. “The rooms were bare except for a thick layer of dust on the floor; my mother asked for jhaaroos and we set to work sweeping it clean.” There was no kitchen in which to cook food and no bathrooms either; “We had to put on burqas and go over to the main section of the college where one of us would keep watch while the others used the facilities.”

Her marriage to Dr Zainulabidin Kamaluddin Kazi (founder of the department of orthopaedic surgery at Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre) took place in 1951, just before she completed her Bachelors in political science. It was an arranged marriage — arranged before she had even been born. “Baba’s friend, Abdur Rehman Siddiqui, said to him that whichever of my sister’s sons is closest in age will be married to your eldest daughter,” says Aziz Fatima, and so it came to be that Dr Kazi, 11 years her senior, became her betrothed. “He was going to England for FRCS studies and requested permission to write to me. My mother said no, because she was worried I would be hurt if he ended up falling for someone there.”

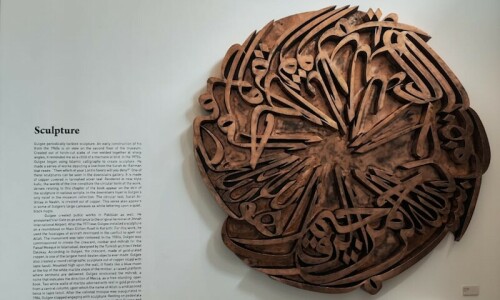

Nothing of the sort happened, though, and the new bride went to live with her husband in what was then Jinnah Central Hospital. She rode her bicycle, played tennis, and raised her children — Faiza, Durriya, Muna and Salahuddin. In 1954 her mother passed away; in 1962 her father. It was when she was in her 60s, visiting her youngest daughter in the United States, that her childhood interest in art sparked again. “An artist named Bob Ross used to do a 45-minute show on television. He’d say, ‘you are going to paint for yourself. If you like what you’ve painted, keep it. If you don’t, whitewash the canvas and paint again.’ I liked that, and when I returned to Pakistan I bought the materials and started painting.”

The walls of her room are covered with canvases depicting scenes of nature. Eschewing easels, she prefers to paint lying down on a sofa. Not concerned with publicity (she’s never exhibited, although her daughter, renowned artist Durriya Kazi, plans to hold a show of her mother’s paintings), she often gives her canvases away as gifts or to those who ask, such as the cleaning woman who requested two paintings to hang in her home in order to impress her daughter’s prospective in-laws.

She once painted a tiger for her neighbourhood fruitwallah because the picture the man originally had looked less like a tiger and more like a monkey, but her affinity for animals extends beyond simply drawing them. Her living space is filled with animals — a dog, five cats that lie curled up at her feet, a cage full of chirping birds hanging over her sofa, and aquariums of fish. Random animals casually stroll into her home, knowing they will be welcomed.

Her living space is filled with animals — a dog, five cats that lie curled up at her feet, a cage full of chirping birds hanging over her sofa, and aquariums of fish. Random animals casually stroll into her home, knowing they will be welcomed. “Once an injured donkey showed up at our door and I treated the wound on his head with some ointment. He came every day for his bit of treatment, and when the wound healed, he brought four or five donkeys along as if to tell them ‘this is the place where you can get help’.”

“Once an injured donkey showed up at our door and I treated the wound on his head with some ointment. He came every day for his bit of treatment, and when the wound healed, he brought four or five donkeys along as if to tell them ‘this is the place where you can get help’.” Word must surely have spread, for how else could anyone explain the audacity of the unknown horse which — on a day with rain pouring down — trotted into her house and made himself comfortable until the rain stopped.

There are numerous such stories, all punctuated with her endearing chuckles. “I went to Empress Market to buy birds, and this man began chatting with me. I told him how lovely the place used to be in my day. After a while he asked me if I’d ever seen the film Titanic. I said I had, and he exclaimed, ‘You look just like the old lady in it!’” She laughs warmly at the memory, and later I wonder what that man would have said, had he only known that the person whom he thought resembled a famous lady on a ship was, in fact, at one time the most famous baby on a ship.

The writer is a Dawn staffer Visit Dawn.com for Aziz Fatima’s video with Mahatma Gandhi

Published in Dawn, EOS, February 26th, 2017