Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has led the BJP to an unexpected sweep of state elections in Uttar Pradesh, a vast, bellwether electoral battleground.

Having defeated regional rivals and now set up the party for consolidation in the upper house of the Indian parliament, Mr Modi has reaffirmed his general election victory of 2014 and established the BJP as India’s pre-eminent political party. What does this mean for Pakistan?

First, Mr Modi and his ultranationalist party resorted to familiar Pakistan-bashing in the run-up to the election. That must stop. Time and again, when faced with tough electoral battles, Mr Modi and his allies have sought an edge by deploying harsh rhetoric against Pakistan.

In the UP campaign, Mr Modi went so far as to suggest that Pakistan was responsible for a deadly train crash in the state last November that killed 148 people. It may just be a domestic campaign tactic, but it causes ripples across the border and further complicates the bilateral relationship.

Second, with a resounding electoral victory, Mr Modi now has an opportunity to pivot and put behind him the recent anti-Pakistan acrimony. Indeed, the leaderships in both India and Pakistan have an opportunity in the months ahead that may not appear again for several years.

In Pakistan, the civilian and military leadership has renewed their commitment to combating terrorism and extremism in all their manifestations, and the extension of Operation Raddul Fasaad to Punjab takes the country one step closer to fulfilling that pledge. Moreover, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and his government have consistently offered talks without preconditions to India. Most recently, during his visit to Turkey last month, Mr Sharif once again emphasised that Pakistan wants good neighbourly relations with India.

Last year, bookended by the Pathankot and Uri attacks, Mr Modi turned his back on his own recognition that dialogue with Pakistan is the only way ahead. It is time Mr Modi and his government returned to the path of dialogue that had so publicly been embraced in late 2015.

Finally, there is an age-old reality that both countries must confront: political will is needed if a meaningful breakthrough is to be achieved. Neither side has demonstrated the necessary will.

When Mr Modi re-engaged Pakistan, the possibility of spoilers attempting to prevent or disrupt bilateral dialogue was real. But political will crumpled in India after the Pathankot attack. And while Mr Sharif has manoeuvred a crackdown against the LeT/JuD leadership, he has been unable to deliver any meaningful progress on the Mumbai attacks-related trials or the Pathankot investigation.

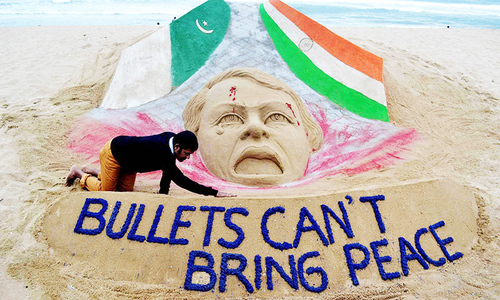

Pakistan and India have a shared past and a common destiny. But to realise that destiny, the leaderships in both countries will need to demonstrate sustained statesmanship.

Published in Dawn, March 13th, 2017