23rd March special: The resolutions after the Resolution

This article was originally published on March 23, 2017.

The first resolve: Head of the All India Muslim League (AIML), Muhammad Ali Jinnah, speaking to party members in Lahore on March 23, 1940. Jinnah was presiding a party session in which the AIML passed a resolution that demanded the creation of separate federations based on Muslim-majority regions in British India. Jinnah resolved to achieve such an arrangement because, he explained, Muslims as a cultural and political polity were distinct from India’s Hindu majority.

A new resolve: Jinnah became Pakistan’s first Governor General in August, 1947. Here he can be seen delivering his first address to Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly. In his address, he resolved to make Pakistan a modern Muslim-majority country where Muslims could advance their economic and cultural aspirations but where communities of all faiths would be facilitated and protected. He said all will be equal citizens in the eyes of the state "because the state has nothing to do with one’s personal religious beliefs."

To demonstrate his resolve of creating a multicultural and pluralistic Muslim-majority country, Jinnah asked the government’s Hindu minister, JN Mandal, to chair the first session of Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly.

From August, 1947 till September, 1948 Pakistan and India shared the same currency notes. Pakistan had emerged as an independent domain of the British Crown, which is why the notes had King George VI’s image on them.

Another resolve: Pakistan’s first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, speaking at the Constituent Assembly in 1949. He was reading out an Objectives Resolution drafted some months after Jinnah’s demise in 1948. The PM announced that Pakistan’s future transformation as a republic and Constitution was to be ‘Islamic.’ The government’s non-Muslim members accused the PM of deviating from Jinnah’s original resolve. But he insisted that the country’s non-Muslim communities need not worry because the future Constitution will be democratic and will safeguard the rights of minorities.

A 1949 Pakistan Railways poster. It was part of the government’s initiative to instil in the people the fact that the Pakistan state had meagre resources.

Between 1950 and 1952, Pakistan’s economy enjoyed a sudden boom when the demand for its agricultural goods grew in the US due to America's war in Korea. As this 1952 article on Karachi in the National Geographic states, Karachi became a boom town because most of the goods were being exported from the city’s port.

The economic boom saw the emergence of Pakistan’s first-ever five-star hotel. It was built in 1951 in Karachi and was called Hotel Metropole.

Angered by the government’s ‘slowness’ to implement the ‘Islamic’ aspects of the Objectives Resolution, religious parties Jamat-i-Islami and Majlis-e-Ahrar used economic turmoil in the Punjab province to launch a violent anti-Ahmadiyya movement. Controversial Punjab chief minister, Mumtaz Daultana, is often accused of 'facilitating' the agitation. The movement was demanding the ouster of the Ahamdiyya from the fold of Islam. Dozens were killed and property belonging to the Ahmadiyya was set on fire. The government called in the military which crushed the movement. The demand of the religious parties was rejected.

During the anti-Ahmadiyya movement, the government and the military distributed a pamphlet authored by Islamic scholar Khalifa Hakim, titled Islam Aur Mullah (Islam and the Mullah). In it, Hakim paraphrased poet and philosopher Muhammad Iqbal’s views on clerics to emphasise that the religious parties were at odds with Jinnah's and Iqbal’s ideas about Islam. The pamphlet was distributed across the Punjab province.

Meanwhile, in the Bengali-dominated East Pakistan, agitation against the imposition of Urdu as the only national language continued. In 1954, after the Muslim League badly lost an election in East Pakistan, Bengali was declared as the country’s second national language. DAWN ran a scathing front-page report on the League’s debacle in East Pakistan at the hands of the United Front.

A Constitutional resolve: In 1956, the Constituent Assembly finally passed the country’s first Constitution. The Constitution declared Pakistan as a republic. The Constitution resolved to turn Pakistan into a parliamentary democracy and an Islamic Republic. It was also decided to celebrate 23rd March as Pakistan Day. The picture shows the indirectly-elected members of the centrist Muslim League, the secular centre-right Republican Party, the leftist National Awami Party, and the right-wing Jamat-e-Islami debating the Constitution.

A cartoon in the Pakistan Times satirises assembly members who had agreed to call Pakistan an Islamic Republic.

The first-ever Pakistan Day parade being held in Karachi on 23rd March, 1956.

The resolve dismissed: President Iskandar Mirza (Republican Party) with the chiefs of Pakistan’s armed forces soon after declaring Pakistan’s first martial law in 1958. The country’s economy had nosedived, there was a spike in incidents of crime and corruption, and constant squabbling between politicians and bureaucrats. Mirza and General Ayub, who had engineered the coup suspended the 1956 Constitution, terming it a way for the politicians "to peddle Islam to meet their cynical political ambitions." Pakistan’s name was changed back to the Republic of Pakistan.

Ayub’s resolve: Ayub, after ousting Mirza, became Pakistan’s president and field marshal in 1959. He resolved to run Pakistan "according to Jinnah’s original vision," which to him meant a robust economy based on rapid industrialisation; a political system which was "more suited to the social realities of Pakistan’s polity" and overseen by a powerful army; and a social ethos constructed through a fusion of ‘Muslim modernism’, widespread education and free-market-enterprise.

Economic growth rose to 6% and manufacturing growth to 8.51% during the Ayub regime’s first six years. New factories and buildings began to emerge. The manufacturing percentage at the time was one of the highest in Asia. Introduction of modern technology, better seeds and fertiliser brought forth a ‘green revolution’ in the agriculture sector.

Students with a lecturer at a college in Lahore in 1962. The economic boom also saw a growth in student enrolment in colleges and universities. There was also an increase in the number of female students.

A 1963 stamp which explained Ayub’s takeover as an economic revolution.

The Minar-e-Pakistan began being built in the early 1960s on the spot in Lahore where the 1940 Resolution was passed.

Passengers being served champagne on a PIA flight in 1966. PIA, launched in 1955, began its meteoric rise as one of the world’s leading airlines in the mid-1960s. It held this position till the early-1980s.

Karachi became the entertainment centre of the country.

A group of Pakistan Air Force pilots during the 1965 Pakistan-India War. The Pakistan Air Force rose to become one of the best and would go on to train fighter pilots in various Middle Eastern countries.

The entrance of Lahore’s historic Badshahi Mosque being renovated in 1967.

The country’s new capital city emerged in 1967. Initially it was supposed to be called Jinnahpur but the government settled for the name Islamabad.

The end: The 1965 war with India badly impacted the economy. A declining economy laid bare the growing gaps between the haves and have-nots. In the late 1960s, a violent movement against the Ayub regime swept the country, denouncing his crony capitalism. Rightists wanted an end to Ayub’s ‘secular regime’ whereas the leftists wanted a socialist setup. Ayub resigned in March, 1969 and handed over power to General Yahya Khan.

Yahya’s resolve, 1969: General Yahya Khan resolved to make Pakistan a parliamentary democracy. He abolished the 1962 Constitution and asked the opposition parties to start work on a new Constitution. For this, he agreed to hold the country’s first-ever elections based on adult franchise.

In 1970 Yahya fulfilled his resolve. Pakistan held its first parliamentary elections based on adult franchise. The Bengali nationalist party, the Awami League, swept the elections in East Pakistan; ZA Bhutto’s populist Pakistan People’s Party won in West Pakistan’s two largest provinces, Punjab and Sindh; the leftist National Awami Party won majorities in NWFP and Balochistan. The religious parties, apart from JUI, were routed.

In 1970, Runa Laila rose to become Pakistan’s first modern pop star.

ZA Bhutto arrives to take over from Yahya in December 1971. The election had set the scene for parliamentary democracy. But the results brought forth the simmering tensions and mistrust between Bengali nationalists in East Pakistan and the West Pakistan ‘establishment.’ A civil war in East Pakistan and then a conflict with India saw East Pakistan breakaway and become Bangladesh. Yahya resigned and handed over power to Bhutto, whose party had won a majority in West Pakistan.

Bhutto’s resolve: During his first address to the nation, Bhutto resolved to "pick up the pieces" and construct "a new Pakistan" which was "dynamic and progressive." He planned to do this by introducing land reforms, reforms in the military and the bureaucracy, and by introducing socialist policies to make the economy ‘people-friendly.’

Bhutto’s ‘socialist’ Jinnah: Bhutto nationalised major industries, claiming he was following Jinnah’s ideas, as this 1973 press ad shows.

A new Constitutional resolve: In 1973, Bhutto managed to conjure a consensus between his ruling party and the opposition in the National Assembly on the contents of a new Constitution. The Constitution was passed and it reintroduced Pakistan as an Islamic Republic and a parliamentary democracy. The photo shows Bhutto announcing the passage of the Constitution at a rally.

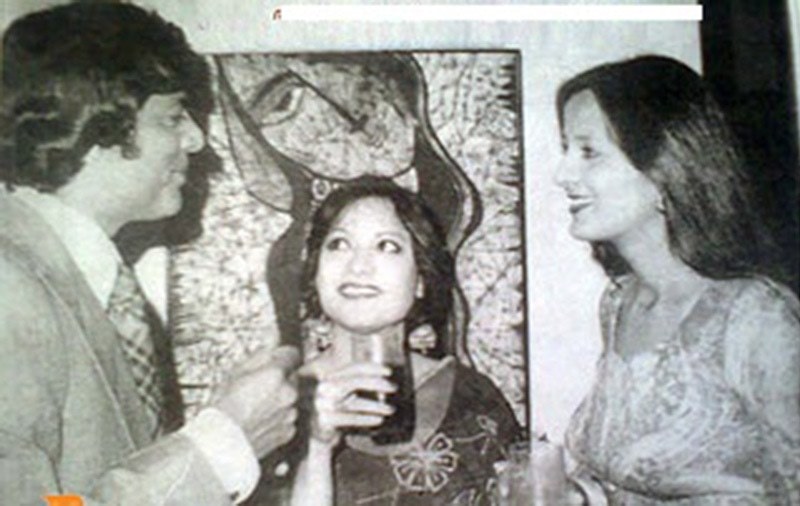

Pakistani film actor Waheed Murad, an unknown guest, and TV actress Saira Kazmi at an art exhibition in 1974. Pakistani film and TV entered their golden age during the Bhutto regime.

In 1974, the ‘Ahmadiyya question’ returned to haunt Pakistan. After a clash between Ahmadiyya youth and members of Jamat-i-Islami’s (JI) student-wing in Rabwah, the JI started a fresh movement to oust the Ahmadiyya from Islam. Bhutto rejected the demand and threatened to use the military against the rioters. Bhutto insisted that the parliament was no place for religious debates. The JI responded by saying that it was because the Constitution had declared Pakistan an Islamic Republic. When the violence intensified and some members of the PPP in the Punjab Assembly too began siding with the demand, Bhutto allowed an anti-Ahmadiyya bill to be tabled in the parliament. The Constitution was amended and the Ahmadiyya were declared non-Muslim.

Bhutto had also resolved to make a ‘third block’ to challenge the 'hegemony' of the Soviet Union and the US. The block was to comprise Muslim countries. For this, Bhutto held a conference in 1974 in Lahore in which heads of states and governments from almost all Muslim countries were invited.

Tourists enjoy a tanga ride outside a hotel in Rawalpindi in 1975. Tourism saw a manifold growth in Pakistan in the 1970s. The government expanded the tourism department and promoted three main types of tourisms: 1) Archeological/Historical Tourism which included trips to ancient sites in Mohenjo-Daro, Lahore, Multan, and Taxila; 2) Nature Tourism which included trips to the northern areas of Pakistan (Swat, Gilgit, and Chitral); and 3) Recreational Tourism which mainly included nightclubs, bars, and beaches of Karachi.

A fleet of PIA planes at the Karachi airport in 1976. In the 1970s, the Karachi airport became one of the busiest in the region and was dubbed the "gateway to Asia."

A hotel in Karachi illuminated during the new year’s eve of 1976.

Another end: Bhutto sitting with party members and his new military chief, Zia-ul-Haq (third from left). Due to an international oil crisis and the Bhutto regime’s haphazard economic policies, turmoil was brewing in the country, especially among the middle and lower middle-classes. Bhutto’s authoritarian attitude had already alienated him from his erstwhile leftist allies. In March, 1977 religious parties began an anti-government movement. The movement demanded Shariah law and removal of the regime. Bhutto closed down nightclubs, banned the sale of alcohol (to Muslims) and promised to reverse his ‘socialist policies.’ But in July ,1977 Zia toppled him in a military coup.

Zia’s resolve: During his first address to the nation in July, 1977 General Zia resolved to turn Pakistan into an ‘Islamic state’ and introduce ‘Islamic’ laws.

Petty criminals, ‘troublesome’ journalists and radical students were regularly flogged in public.

When in 1979 the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, the US and Saudi Arabia began to aid the Zia regime by pouring arms and money to facilitate a ‘jihad’ against the Soviets from Pakistan’s northern areas. Here, a Pakistani Pashtun declares war against the Soviets in the tribal areas of Pakistan.

1981: Unprecedented aid from the US and Saudi Arabia and the Zia regime’s pro-business policies helped Pakistan enjoy an economic boom in the early 1980s.

Pakistan hockey reached the pinnacle of its prowess when Pakistan won the 1982 world cup. This was Pakistan’s third world cup title. It will win it one more time before dramatically declining as a hockey power.

Students protest against the death of a colleague who was crushed under the wheels of a public bus in Karachi in 1985. This gave birth to vicious ethnic riots in the city. Karachi had begun to boil over due to ethnic tensions, a rising crime rate, and drug and gun mafias.

When the Zia regime began to empower extreme clerics to boost the ‘jihad’ in Afghanistan, violent sectarian organisations sprang up. By the late 1980s, sectarian violence spread across the Punjab.

When an alleged bomb went off on a plane carrying Zia in 1988, democracy returned to Pakistan. Benazir Bhutto’s PPP won the 1988 election.

Zia’s demise saw a local pop music explosion which lasted across the 1990s

Benazir’s resolve: Benazir Bhutto taking oath in 1988. She resolved to make Pakistan a democracy again and reverse Zia’s ‘reactionary policies.’ But when American aid vanished after the Soviets left Afghanistan, she did not inherit the 1980s economic boom. But she did receive Zia’s other legacies such as institutional corruption, drug mafias, and sectarian and ethnic violence. Coupled with her own government’s utter incompetence, her first term was a disaster. She would be reelected in 1993 to fall yet again in 1996.

Nawaz’s resolve: Nawaz Sharif taking oath in 1990. His Pakistan Muslim League came to power after the 1990 elections. He resolved to "rekindle Zia’s mission" and not let the PPP "derail Zia’s Islamization." He also promised pro-business policies. Unable to check an economy and polity spiraling out of control, he too fell. In 1997 he was reelected to fall again in 1999.

But as the country struggled to come to terms with things such as sectarian and ethnic violence, corruption, and a sliding economy, its cricket team won the 1992 world cup.

Yet another end: Soldiers climb the gates of PTV during the General Parvez Musharrf coup in 1999. He toppled the second Nawaz regime.

Musharraf’s resolve: Musharraf resolved to put Pakistan on the path which Jinnah had envisioned. To achieve this, he said he will use a doctrine called ‘enlightened moderation.’ This doctrine was actually an updated version of Ayub Khan’s fusion of Muslim modernism, free-market enterprise and a controlled democracy overseen by the military. Musharraf banned various sectarian and extremist organisations, eased ties with India, exiled Nawaz and Benazir and became an ally in America’s War on Terror.

In its first six years, the Musharraf regime remained largely popular. Crime, sectarian and ethnic violence decreased, the economy picked up and the urban middle-class expanded. Cities became boom towns. A revival of Pakistani cinema started to take shape as well.

The bubble bursts: In 2007, the lawyers’ movement began sweeping the country against the regime. The economy had begun to recede and Al-Qaeda increased its attacks on Pakistani soil. The weakening regime’s half-baked measures could not stem the radicalisation of the society. The same year, Benazir was assassinated by extremists and Musharraf seemed to have lost control. He was forced to resign after the PPP and PML-N won the 2008 elections.

More chaos: Extremist terror and mindset gripped the country during the new PPP government. The regime seemed all at sea, plagued by incompetence, corruption, assassinations, political intrigues and a military establishment busy playing mind games with politicians. By 2013, the country stood isolated and wrecked.

A new resolve: When Nawaz Sharif was elected prime minster for the third time, his government seemed paralysed as Pakistan continued to plunge into an abyss. Then, the tragic deaths of school children in an extremist terror attack in 2014 galvanised the government and the new military chief Raheel Sharif to actually reverse political and military policies of the last many years.

The government, military and opposition parties got together and through a joint-resolution, gave the green light to a widespread military operation against extremist and sectarian groups, and also initiate a National Action Plan (NAP) to introduce reforms which would reverse the mindset that facilitates radicalisation and extremism in society. By 2016, the percentage of terror attacks and crime had appreciably lessened. The struggle continues to finally construct Jinnah’s Pakistan.