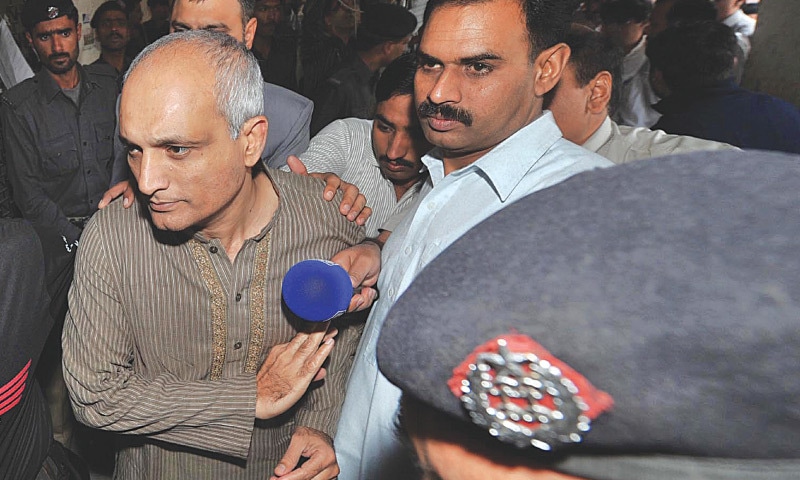

"Tell me,” Munaf Kalia challenged his interrogator immediately after his arrest, “who is not involved in this?” The question hung over the ensuing investigation into money laundering by Pakistan’s largest forex company. The answer came three years later when all involved were acquitted of all charges. “Politicians, ministers, generals, businessmen, tell me who is not a user of our services?”

That was in 2008, the heady year of catastrophe. The financial system had nearly collapsed, with the stock market shut and banks seeing withdrawals so rapidly that fears of a large-scale run the likes of which we have never seen in our history were rising. The country’s foreign exchange reserves dropped from what was touted only a year earlier as “record high” to such a precarious level that the government had to approach the IMF for an emergency lifeline. And the government launched a massive crackdown against illegal hawala traders, money changers who engaged in the illegal transfer of foreign exchange into and out of the country, though in those days almost all the traffic was outbound.

Investigators estimated that Khanani and Kalia (K&K) —of which Kalia was a director — held between 25 to 30 percent of the hawala market at that time, and had transferred close to 104 billion rupees in the 13 months leading up to their arrest. Press reports speculated that these transfers were responsible for depleting Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves, forcing the country to seek an IMF bailout, but the estimated amount would not be sufficient to bring the economy to its knees.

What those transfers, and the subsequent investigation of the enterprise, did reveal though was how far and wide the web of money laundering is spread within Pakistan’s economy, and how central it is to its normal functioning.

Flush with cash

Pakistan has one of the world’s highest cash-to-bank deposit ratios. The amount of money that swirls around the economy in cash is more than one third of total bank deposits. Its fractured relationship with neighbours has also helped create an informal payment systems and a large overland trade designed to bypass normal customs channels. Finally, capital accumulation domestically finds it difficult to locate investment opportunities within the country due to the rigid nature of the industrial system which has not changed much for the past three decades, creating a built-in incentive to accumulate assets outside the country.

For K&K, all these constraints were an opportunity. Their headquarters housed more than 35 servers dedicated to processing money transfer requests received through a network of up to 4,000 branches and franchisees around the country. They had their own software house, located in a five-storey building with hundreds of employees, dedicated to building and upgrading money-transfer software that would connect their branch network across Pakistan with thousands of other branches and franchises spread around the world. Whenever the amount of money travelling through their system approached the regulatory limit allowed to them as a registered ‘A’-class exchange company, the system would automatically route the transfer through their parallel hawala operation. They sold the software to other exchange companies in addition to using it themselves.

For the regulator, the biggest clue that large amounts of money are being routed to the parallel hawala network is when the spread between the kerb rate and the market rate, meaning the exchange rate advertised for a particular currency and the rate at which it is actually being sold, begins to climb. Throughout 2007 this spread climbed, reaching almost 10 rupees by the time the law closed in on K&K. Where the dollar was advertised for 70 rupees, it was going for 80 rupees in the market, and upwards of 85 rupees in the hawala market.

Contrary to popular misconception, hawala actually uses the banking system extensively. The theory about hawala transfers says that no physical movement of money is required, since funds coming to the recipient country are settled against funds going out to the country from where the funds are remitted. So remittances coming to Pakistan from the UAE, for example, would be taken by a hawala trader there, and the requisite amount of rupees would be issued by that trader’s agent here in Pakistan.

$10bn: MONEY LAUNDERED OUT OF PAKISTAN EVERY YEAR, ACCORDING TO US STATE DEPARTMENT ESTIMATES

But the theory describes a system as it would operate in an ideal situation. There would be a total lack of any physical movement of funds in a hawala operation between two countries only if the total flow between both of them was exactly equal.

In practice, the flow of funds changes from time to time, and more often than not, does not match between the sending and the receiving countries. This means money will accumulate in some nodes of the traders system while it depletes from others, necessitating a periodic squaring of accounts between various nodes in the system. This squaring of accounts takes place daily.

Funds sent abroad are also sent via a bank account, usually opened in the name of the exchange company, as well as a large array of “benami” accounts — accounts opened in someone’s name but operated by other people — which they use for their hawala operation. In the case of K&K, the central node in their system was Al Zarooni Exchange, located on Naif Road in Dubai, which received funds from across the world. The sender would be issued a code, which he or she could take to any K&K branch or franchise anywhere in the world and obtain their funds accordingly. Once cleared, their position would be closed.

Their paid-up capital, or the ceiling that they were allowed to legally transact under the terms of their license, was 25 crore rupees daily, but the funds landing in Al Zarooni were far in excess. By 2015, the US Treasury department claimed that the K&K enterprise was moving “billions of dollars” annually on behalf of a global clientele. When he was arrested in a sting in 2015, Altaf Khanani was laundering money for an American law enforcement agent and charging him 3 percent commission.

In Pakistan the commissions varied, depending on how dirty the money was. Simple tax-evaded wealth could move out for a nominal fee, but funds connected with narcotics, kickbacks or extortion could command fees as high as 20 percent of the amount being transferred.

Channels of deception

Exchange companies are only one way to transfer funds into or out of the country without arousing the authorities’ suspicions. The State Department has estimated that 10 billion dollars are laundered out of Pakistan every year, meaning the channels through which to move this quantity of money would be numerous.

There are numerous ways that black money accumulates in an economy like Pakistan’s. Ill gotten proceeds of powerful individuals are only a small amount of the total. By far the largest amount of black money accumulates outside the country in the form of mis-declaration of trade. Exporters will routinely understate the amount shown in their Letter of Credit (L/C) opened with a bank, preferring to receive the rest into an offshore account.

The State Bank has warned that “a tightening regulatory landscape governing cross-border money transfers in the US (which has increased compliance costs for banks and money transfer operators)” could end up with implications for Pakistan’s banks, especially their ability to interact with the outside world through correspondent banking relationships.

Likewise, importers will routinely understate the value of the consignment they are importing to avoid customs duties, and remit the balance through an exchange company, or from offshore accounts held abroad. According to estimates of reported trade between Pakistan and China, the difference in the Chinese and Pakistani reported data of all exports and imports between the two countries is as high as 5 billion dollars, which is slightly more than half of the reported trade deficit between the two countries.

When poring through K&K servers, law enforcement also came across examples of importers who had mis-declared the value of their import consignments by about 50 percent. This volume of accumulation of black money will always require powerful channels for the movement of these funds into and out of the country, for which a variety of pathways have been carved out over the decades.

Making exceptions

One of the most straightforward of pathways is also the most direct. A simple loophole in the Income Tax Ordinance of 2001 deals specifically with unexplained income or assets. This is the infamous Section 111 which empowers the tax collector to treat as taxable all income and assets for which no satisfactory explanation is offered by the taxpayer, but in subsection 4, it creates an exception.

That subsection applies only to individuals, not companies, and reads thus:

“Sub-section (1) does not apply, — (a) to any amount of foreign exchange remitted from outside Pakistan through normal banking channels that is encashed into rupees by a scheduled bank and a certificate from such bank is produced to that effect.”

This simple loophole means anyone can bring in any amount of foreign exchange into the country, provided it “is encashed into rupees by a scheduled bank” immediately upon arrival, and the funds thus received cannot be treated as taxable.

But there is a slight problem with Section 111(4). It provides some measure of protection from the tax authorities, but not from law enforcement. So if the funds being brought in can be demonstrably connected with illicit activity, such as narcotics exports or kickbacks, the transfer can be frozen and investigation can begin under another law known as the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act. There are a number of such cases on record, with the most recent being a 65 million dollars transfer that was coming in from Malaysia, purportedly for investment into “a newly launched housing colony in Karachi” which was frozen by the State Bank after the bank filed a Suspicious Transaction Report (STR).

Those transacting in this market cannot brook exposure or delays. Section 111(4) provides some sanctuary to the small remitter, who might be receiving one or two million dollars from time to time, but for the large player, it can present risks.

This is where trade-related money laundering comes in. This is one of the oldest, and most widely used channels for illicitly moving money across national jurisdictions, as well as moving illicit money out of the country. The mechanism is simple: I own a company in Pakistan, and am in possession of a large sum of money that I want to move out of the country without arousing suspicion. So I register a company in Dubai, of which a family member could be the ultimate beneficial owner.

The Dubai company bills my company for a “service” that I have purchased, for example software or a consultancy, or brokering service in locating an export client for my “product”. Against that bill I make a payment. Or alternatively, my Dubai company “sells” me a container full of shoes, and charges me an outlandishly large sum for it, which I pay through an L/C. I can import or export a fictitious cargo (the container itself could be full of junk) but the L/C provides a safe and ready way to transfer the funds out of the country without arousing undue suspicion.

There are numerous ways that black money accumulates in an economy like Pakistan’s. Ill gotten proceeds of powerful individuals are only a small amount of the total. By far the largest amount of black money accumulates outside the country in the form of mis-declaration of trade. By far the largest amount of black money accumulates outside the country in the form of mis-declaration of trade. Exporters will routinely understate the amount shown in their Letter of Credit opened with a bank, preferring to receive the rest into an offshore account.

The only suspicion that would come into play would be when the cargo undergoes customs valuation. Export consignments are typically not valued by customs. A simple goods declaration form is enough for exports. Import consignments undergo valuation by Customs, but since they are looking primarily for under-invoicing, an over-invoiced import (whose real purpose is to allow the funds to go abroad) passes quite easily, especially considering Customs staff is incentivised to maximise revenue through customs duties, which are a function of the consignment’s value.

It is next to impossible to figure out how much money comes in or leaves the country under this mechanism. Empty containers leave the country regularly due to a large trade deficit that Pakistan runs, which results in containers accumulating within the country so the cost of the container is low. The cost of exporting “trash” is not very large.

Trade related money laundering works better for those who have large sums to send or receive. It is more cumbersome than a straightforward remittance, but offers the benefit of being immune to regulatory scrutiny. The only party that can actually intercept this form of money laundering is the Customs authorities, who at the moment are neither tasked nor incentivised for this purpose.

The pathways to move money in and out of the country are numerous, and given the size of the informal sector in Pakistan, the volumes involved in this stealthy enterprise are also substantial. All manner of black money, whether illicit or tax-evaded, utilises these channels, so the number and type of stakeholders are also very diverse, something Munaf Kalia alluded to when he challenged his interrogator to “tell me who is not involved in this business”.

Tightening noose

Since at least 2012, governments around the world are coming under increasing pressure to choke off illicit pathways of money transfer since they are used extensively for terror financing and moving funds from criminal activity. The regulatory framework is being tightened, and pressure to prevent the formal banking system from being used for illicit movement of funds is mounting. The State Bank has warned that “a tightening regulatory landscape governing cross-border money transfers in the US (which has increased compliance costs for banks and money transfer operators)” could end up with implications for Pakistan’s banks, especially their ability to interact with the outside world through correspondent banking relationships.

Most recently, a long standing demand from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to move more visibly and vigorously against individuals and entities designated as terrorists under UN Resolution 1267 saw a flurry of activity in February, when Hafiz Saeed was placed under house arrest, and the government announced that his name along with an associate was being added to the Fourth Schedule of the Anti Terror Act.

The move was reportedly triggered by a warning from the Asia Pacific Group, a sub grouping of the FATF, that the continued freedom of movement and fund-raising by individuals designated as terrorists by the United Nations could have consequences for Pakistan’s banking system. The warning was repeated in the latest State Department report titled International Narcotics Control Strategy Report that in Pakistan, “UN-designated groups continue to be able to solicit donations openly without apparent government reaction” and “Pakistan does not fully implement UN sanctions obligations uniformly against all designated parties.”

In the years since this report has been issued, this was the first time that explicit mention of this was made, indicating that the country’s financial system’s vulnerability to misuse for illicit purposes, including terror financing, is becoming a growing concern. The next meeting of the FATF to assess the steps taken by Pakistan against these designated individuals is in June.

Determined action against UN designated parties is not the only area where Pakistan law enforcement and judicial authorities have struggled to meet the challenges posed by the illicit payments system, including money laundering. Hawala traders routinely get netted by the FIA in raids, but the prosecution inevitably falls through.

Crimes and misdemeanours

Last year the FIA conducted a series of raids in Peshawar’s currency market near Yadgar Chowk, arresting 45 people and seizing documents which they claimed showed active hawala operations. But a perusal of court cases against hawala dealers shows that they inevitably receive bail. In some cases, bail is granted because the court said that the prosecution needs to establish that the funds seized during the raid were proceeds of crime. In another case, the court said the prosecution failed to connect the arrested individuals with “the commission of the alleged offence”.

In another interesting judgement, the Sind High Court found that “the offense of money laundering will only be attracted if the money’s, assets, property etc are acquired through the proceeds of crime…and there is an attempt to in effect hide the illegal source from there the funds came.” This, the court said, means it is necessary to undertake an investigation “to identify a suspicious transaction and then work backward to see if [it] may have arisen out of proceeds of crime which are the fruits of a predicate offense”.

The courts are widely interpreting the Anti Money Laundering Act to mean that money laundering can only be said to have taken place when the funds in question can be shown to be “proceeds of crime”. The channel through which the funds may have moved, whether hawala or deliberate mis-declaration of a cargo’s value, therefore stands beyond the reach of the law.

Pakistan’s financial system is increasingly caught in this three way bind. First is a tightening global regime that seeks to aggressively squeeze the space in the banking system that illicit actors and designated terrorists can use to advance their purposes. Second, a large and thriving informal sector and large pools of tax evaded wealth, that make illicit channels for the movement of funds salient to the operation of the economy. And finally, a legal apparatus that cannot distinguish between the illicit movement of funds and the movement of illicit funds.

The writer is a member of staff.

He tweets @KhurramHusain

Published in Dawn, EOS, March 26th, 2017