Dr Sajida Hussain*, 54, a general physician does not know what it is like to be happy.

"My son got engaged and my daughter's nikah was performed recently; I did everything from organising the two dinners to shopping for both my daughter-in-law and daughter...everything went perfectly but if you ask me honestly, even these big milestones in my life failed to excite me."

She pines for that zing of pleasant emotion most people take for granted, but which eludes her. "I have everything ─ doting children, money, a successful career ─ what I don't have is inner peace and happiness," she says in a deadpan voice.

The last time she remembers feeling joyful and elated was on her 12th birthday when her father had insisted on a huge celebration since he knew he was not going to live much longer. "My father doted on me and my littlest wishes were fulfilled. I just had to ask!" she remembers fondly.

Hussain has been on anti-depressants for a very long time, almost 20 years, since the time she first tried to commit suicide, when her second child was just three. But no one knows, neither her husband nor even her grown up children. But her battle with depression began much earlier. She pins it to her marriage.

But depression never makes it to the discussion table. When it is spoken about it, is always in reference to others and in uncomfortable and hushed tones. People hardly admit they are suffering from it.

What causes depression?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) says depression is often caused by a combination of physical, psychological, and social factors. These are:

- A family history of depression

- Poor nutrition

- Having chronic physical illnesses like hypertension, diabetes, cancers, thyroid disorders and Parkinson disease

- Repeated exposure to extreme stressors like war, conflict or natural disasters

- Use of licit and illicit drugs

- Rapid change in life situations like marriage, childbirth, loss of job or partner

- Experiencing adversity and abuse in childhood like early loss of parent(s) or non-responsive and non-stimulating parenting

- Long-term difficulties like financial problems, belonging to a minority group, and marital difficulties

"My brother has been on anti-depressants and sleeping pills and has not come out of his room in 20 years, says 53-year old Amena Saeed*, working in a government office in Karachi.

"The doctor has prescribed him sleeping pills to vanquish the demons that haunt him after his best friend died in a car accident which he was driving," she said, adding: "He has attempted suicides several times and someone has to be on his guard all the time."

It's not easy and takes a toll on the care providers, says Saeed who is single and the only family member after their parents passed away.

Since last year, the doctor has prescribed her with anti-depressants as well as sleeping pills after she told him her work was getting affected. But she is not making it public. "I will be sacked," she said.

Even Hussain, a practising doctor refuses to come out of the closet. "There is still a lot of stigmas attached to mental illnesses and if people find out I am on 'paglon wali dawai' [medicines for the mentally challenged], it will not only destroy my career but my social standing."

Stigma is not just peculiar to Pakistan but is a global phenomenon. According to WHO, "Lack of support for people with mental disorders, coupled with a fear of stigma, prevents many from accessing the treatment they need to live a healthy and productive live".

But while she wants to remain tight-lipped, she admits talking to a complete stranger over the phone, thereby providing a cloak of anonymity, is "cathartic".

While both Hussain's brother and her son had also been diagnosed and treated for depression, she is emphatic her condition has nothing to do with the genetic factor, and blames her circumstances.

"I was mistreated by my mother-in-law and my husband would just look on. I felt lonely and unloved and even wanted to abort my first child," she recalls.

But now when so much has changed, she continues to carry the baggage of her past. "My husband and my mother in law dote on me now, but it's too late. I cannot forgive or forget how I was treated," she said with a tremor in her voice.

Her coping mechanism during her earlier phase was finding respite in work and living in separate bedrooms. "I would spend all my time and energy outside my home and come home to help my children with their homework."

It was when her eldest child, her son, who was just 14, tried to commit suicide, she was shaken from the stupor. "I decided I needed to seek professional help for him."

Hussain is the first to acknowledge that silence surrounding depression is the biggest barrier to seeking treatment and which often leads to delays, non-detection and often inappropriate treatment.

"Had I watched my son closely and given him time, maybe I could have diagnosed the disorder much earlier; instead I made the problem worse by sending him away to a hostel where he was alone and scared and took that drastic step." In retrospect, she thinks it was a mistake to shut all communication channels with everyone to keep her sanity.

Today, when her son is getting ready for marriage, he disclosed to her that it disturbed him as a child to see his parents sleeping in separate bedrooms.

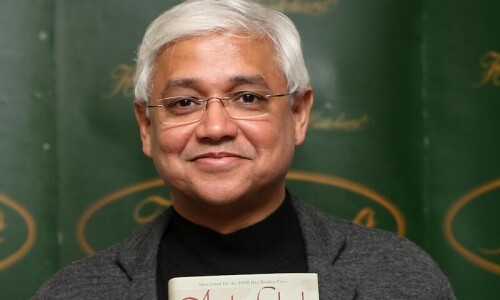

The silence does not really surprise Dr Murad Moosa Khan, professor of psychiatry at the Aga Khan University, "because when you combine lack of awareness with lack of health systems then people will suffer silently.

He finds it worrisome, nevertheless. "Because when people suffer they are not productive. This affects the person, his/her family and ultimately the whole community."

Symptoms to look out for:

- Indecisiveness

- Change in appetite

- Restlessness

- Sleeping more or less

- Feelings of worthlessness

- Guilt or hopelessness

- Anxiety

- Thoughts of self-harm

- Reduced concentration

- Thoughts of suicide and can even lead to suicide.

Depression affects more than 300 million people worldwide (an increase of more than 18 per cent between 2005 and 2015) and is the single leading cause of disability around the world. And while the social cost is incalculable, the economic costs for individuals, communities and nations is estimated to be more than US$ 1 trillion globally according to WHO.

A 2005-2006 Aga Khan University study comes up with grimmer statistics for Pakistan putting the figure for prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders in Pakistan at 34pc. It put schizophrenia and bipolar disorders at between 1-2pc of the population. And 15 of Pakistani kids suffered some form of mental health problems.

Another disturbing statistic shared by Dr Khan is the psychiatrist population ratio (not psychiatrist patient ration as we don’t know how many patients there are) which is one psychiatrist to 0.5-1 million people. The Royal College of Psychiatrists, in the UK, recommends one psychiatrist to 25,000 population. It is the same with psychologists.

Most people, he said, sought help when it starts to affect their day to day activities. "Even when one family member suffers from depression, the entire family gets affected.

However, over the years, to some extent, he says the stigma around depression has decreased as awareness has increased.

Today people acknowledge that depression is the result of a multitude of factors including genetic, environment, personality, upbringing, social etc that come together to make a person vulnerable to it. In addition, disproportionately high poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, lack of health and education facilities, poor housing, poor living conditions, pollution, no regulation of food, medicines, hospitals, poor justice system just aggravate the situation further.

And if depression is not treated, it can lead to suicide. In fact, it is the second leading cause of death among 15-29-year-olds after fatal road accidents. In Pakistan, too, the incidence of suicide had gone up. Citing WHO, Dr Khan said every year between 13,000-14,000 Pakistanis committed suicide, in addition to the 130,000-300,000 attempts.

Attempting suicide is considered a criminal offence under Section 325 of the Pakistan Penal Code and punishable by imprisonment or a fine, or both. Dr Khan, who is president-elect of the International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP) emphasised that given the high numbers of it attempted suicides it should act as a wake-up call for the government to rethink and decriminalise it so that people who have psychological problems can seek help without fear from legal authorities.

"The present law is based on the tenet of Islam that considers suicide as a sin. What is interesting is that while the Holy Quran talks about suicide specifically it does not talk about attempted suicide but legal authorities in many Muslim countries use the edicts of the Quran to apply to attempted suicide - which is wrong," he explained.

"Unfortunately nobody is working on it because firstly, no one is interested in psychiatric illnesses or suicide at the population level; secondly due to the religious edicts against suicide, no one wants to address it for fear of a religious backlash; thirdly, the psychiatrists association of Pakistan is not interested in pursuing this. They are more interested in going to conferences at pharmaceutical industry’s expenses," pointed out Dr Khan derisively.

And yet it was important to make the distinction between human distress and clinical depression. "The level of distress is very high in Pakistan because of dismal social conditions. However, rates of clinical depression (when it becomes a medical disorder, as opposed to feeling unhappy or dissatisfied with life) are about 10pc of the adult population and a similar number of children.

In the last couple of years, Indian actors Deepika Padukone and film producer Karan Johar Jolie etc have disclosed their battles with depression. "In the west actors, musicians, politicians and other celebrities frequently join public awareness campaigns to urge people to seek help for common medical illnesses (including mental illnesses). Everyone knows about the struggles of people like actors Robin Williams, Jim Carrey and Ashley Judd, musician Kurt Cobain, astronaut Buzz Aldrin and even US presidents Abraham Lincoln and John Adams," points out Lahore-based Dr Ali Madeeh Hashmi, an associate professor of psychiatry at King Edward Medical University.

"A celebrity endorsement helps bring more awareness, more research and more money for treatment and prevention," Dr Hashmi says.

What can you do if you think you are depressed?

- Talk to someone you trust

- Stay connected with family and friends

- Seek professional help

- Stick to regular eating and sleeping habits

- Keep up with activities you used to enjoy

- Accept that you might have depression

In Pakistan, too there are a couple of well-known people who suffered from mental illness like writer Saadat Hasan Manto and actor Roohi Bano, but by and large the subject remains a taboo with no one willing to speak on the record, he said and adds: "If more famous people with mental illness would come forward publicly to seek help, it would help raise awareness and reduce stigma."

But Dr Khan thinks otherwise. "It is no good these well-to-do people, who can afford the best treatment in the world- either for their depression or for their heart talk about something like depression- which a poor person in Orangi or in a slums in Bombay is listening to on TV and can relate to well but can do nothing about? She can neither afford the doctor's consultation fees nor the cost of medicines; she will feel even more depressed!" He said it can do more harm than good.

He said these campaigns should be done thoughtfully and sensitively ─ with factual information with mention of resources where and how to seek affordable help.

Affordable psychiatric care in Karachi:

- Pakistan Association of Mental Health (PAMH), charity clinic in Saddar (near Prince cinema)

- Karavan-e-Hayat Psychiatric Clinics, Kemari and Punjab Colony

- Psychiatry clinics at Civil Hospitals, Jinnah Hospital, Abbasi Shaheed Hospital.

- Psychiatry clinics at Aga Khan Hospital, low cost (Rs. 640 per visit)

Interestingly, depression is not a poor man's disease. Everyone who is poor and has nothing is not depressed. Personal coping and resiliency factors often determine whether someone is going to able to overcome the odds and survive or become despondent and depressed, explains Dr Khan. Some of his patients belong to some of the richest families of Pakistan ─ "multi-billionaires who have everything and more".

"In almost all such cases there is imbalance ─ either genetic factors for depression may be very strong or they may be leading imbalanced lives ─ indulging in substance abuse or find themselves in destructive relationships ─ that may affect their self-worth and image leading them to become clinically depressed," he says.

*Names have been changed to protect identity.