The buzz about Balochistan in the rest of the country involves China but at a local blood bank in Quetta, jihad in Kashmir and Myanmar takes centre stage. An activist of the Falah-i-Insaniat Foundation (FIF) — the charity wing of the once-proscribed Jamaat-ud-Daawa (JuD) — is the protagonist, and he is armed with a copy of the paper Ahrar, the JuD’s organ, and other literature propounding jihad.

“You must read these regularly if you want to be good Muslims,” he exhorts others around him. “It will also help you live your lives according to the sunnah.”

Talk of jihad by non-state actors was supposed to die down in the wake of the National Action Plan (NAP). But the FIF activist proudly tells the blood bank employees that their literature is sent across Balochistan — particularly in the northern areas dominated by Pakhtun populations. “Our organisation is better organised there than in Baloch-dominated areas,” he explains to the staff.

The exchange is informal but the FIF activist is unrelenting in his mission: “If someone cannot afford to buy our paper and literature, which are sold at throwaway prices, we also distribute them without taking a single paisa.”

A province in the developmental limelight is also home to competing ideologies. What is Balochistan reading and how does that play out in the province’s politics?

Many blood bank employees are university graduates; most of them show their keen interest in the literature being distributed by the FIF activist. “Yes, of course!” says young Ziauddin*. “We want to read literature that enables us to be successful in both worlds — the finite world and the hereafter. Why read only those books that will land us good jobs?”

Contrary to popular belief, the proliferation of jihadi thought has become an unwanted problem for authorities in Balochistan. Although outfits such as FIF are widely believed to be propped up by authorities as a counter to Baloch militancy — as exhibited by the impunity with which the FIF activist could spread his message — security forces last year arrested at least 34 people during raids in various parts of the province and particularly in the capital city, Quetta.

This change is attributed to the NAP by senior security officials. Independent observers, however, also attribute greater Chinese presence in Balochistan as the key motivator to rein in sectarian outfits.

“Following the enforcement of NAP, we drew up a list of [what constitutes] hate-inciting speeches, materials and sermons,” explains Abdul Razzaque Cheema, the Capital City Police Officer (CCPO) of Quetta. “We have been cracking down [on activities that match our description]. And as a result, hate speech and material in the city are nowhere to be found. Unlike the past, there is no wall-chalking nor are there any sectarian slogans painted on the city’s walls.”

In certain raids, jihadi literature was recovered along with arms and ammunition. “We have also cracked down on mobile shops, CD shops, and other devices containing hate literature,” says the CCPO. “After recovering hate material, mobile phones, CDs etc, we present them in court. With the permission of the court, we destroy them.”

CCPO Cheema adds that the police have now changed their modus operandi: crackdowns are not conducted “in the open” anymore. Rallies and political gatherings are also being “monitored closely” for any hate-speech.

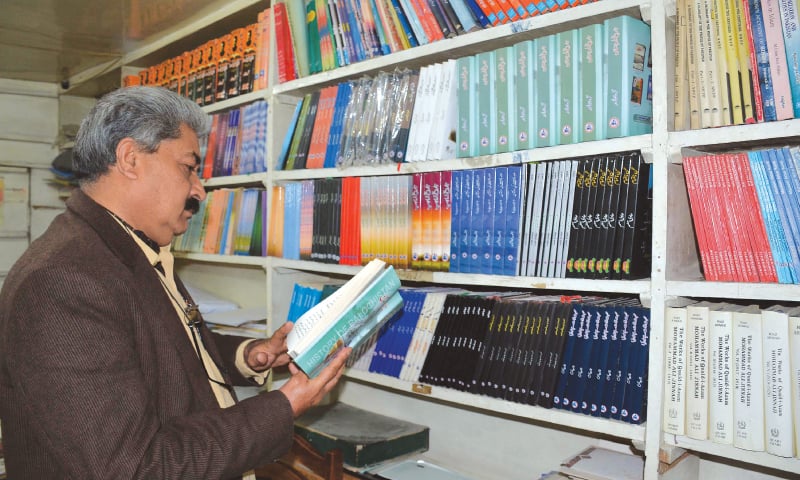

But while the police remain intent on maintaining vigil over speech, it is textual material that is proving problematic. Compared to the number of general bookshops in Quetta or elsewhere in the province for that matter, a growing number of bookshops have sprouted where jihadi and other religious literature is sold. In most cases, the state has been unable to check the proliferation of this material.

“In Balochistan, the Pakistani state’s inability to capture citizens’ imagination has resulted in other ideas and narratives taking root. And over the years, the various political positions have only become more polar.

In other words, a significant section of Balochistan is reading jihadi material without any meaningful response by the state. In this vacuum, is the secular outlook of Balochistan changing?

IDEAS, POWER AND GEOGRAPHY

The preference of what is being read where in Balochistan represents a political trend.

In the Makran belt of the province — home to various waves of separatist movements — left-wing literature is read more than religious material or official text books. Thanks to the region’s proximity with the Gulf and an absence of tribalism, a middle class bulge is ever-growing. This is why Makran is far ahead in terms of education than the tribal areas in eastern and central Balochistan. It is also why the Baloch Students Organisation (BSO), a leftist group formed during the Cold War era in 1967, has flourished in Makran.

The BSO has some influence in the tribal areas but the education ratio there is far below that of Makran. As a result, BSO’s propaganda hasn’t held much sway in tribal areas. Both left and right-wing literature is read in this belt but neither prevails over the other in an ideological sense.

In the Pakhtun belt, right-wing literature is most widely read — as was alluded to by the FIF activist. The Pakhtun area is religiously inclined because of its proximity with Afghanistan and the rise of religious politics in Afghanistan during the General Ziaul Haq era.

Despite polar ideological preferences, however, the absence of a strong state narrative has had larger ramifications. Although General Ashfaq Pervez Kayani had boasted in August 2013 that over 20‚000 Baloch students had been enrolled in the Pakistan Army and the FC-run educational institutions, the situation has now changed. In Balochistan, the Pakistani state’s inability to capture citizens’ imagination has resulted in other ideas and narratives taking root. And over the years, the various political positions have only become more polar.

THE BATTLE FOR QUETTA

In theory, the provincial capital should be a potpourri of ideas. Its universities and colleges should be avenues of polemics — more debate only creates a more democratic society.

“Three [kinds of] ideas are discussed in Quetta,” says Dr Shah Mohammad Marri of the Sangat Academy of Sciences (SAS). “Nationalism; Marxism; Obscurantism. The dominant discussion in Quetta is nationalism.”

Dr Marri is part of a collective of enlightened writers which also includes Waheed Zaheer, Professor Javed Akhtar, Jiand Khan Jamaldin, and Abid Mir. They have gathered under the SAS umbrella and thus far, managed to publish around 25 books, including in Balochi, Brahui, Pashto and Urdu. They also encourage and focus on Balochistan-based scholarship in culture, history, anthropology, and indigenous languages among others.

Nationalism has historically been the dominant thought in Quetta in part because of its reliance on oral traditions and debate. “Unlike Marxism, nationalism has no books. It is discussed [rather than read],” explains Dr Marri. “In the past, people were semi-literate while the new generation is literate. They read books and they discuss different ideas.”

While Urdu is the country’s national language, Balochi does not enjoy much cultural capital within governance structures. The heroes of Balochi literature, for example, are not the heroes of official literature printed in Urdu. In Urdu literature, these same Baloch heroes are described as trouble-makers and unpatriotic.

But both Baloch nationalism and Marxism have been anathema in official Pakistani circles — they are viewed as ideologies that undermine the notion of a homogenous Pakistani nationalism and instead, promote separatism. As a result, those curious about ideas and ideologies may find themselves in hot waters with authorities because of the inherent mistrust of ethno-nationalism and Marxism among official Pakistani circles.

The recent past, however, has seen the rising popularity of theological literature in Quetta.

Like the rest of the country, jihadi literature first made its way into Balochistan in 1979 along with the Afghan war. But while other parts of the country ultimately stemmed the flow of those beliefs, jihadi literature and practices started thriving in Quetta. In the suburbs of the city, sectarian literature would openly be sold at various shops.

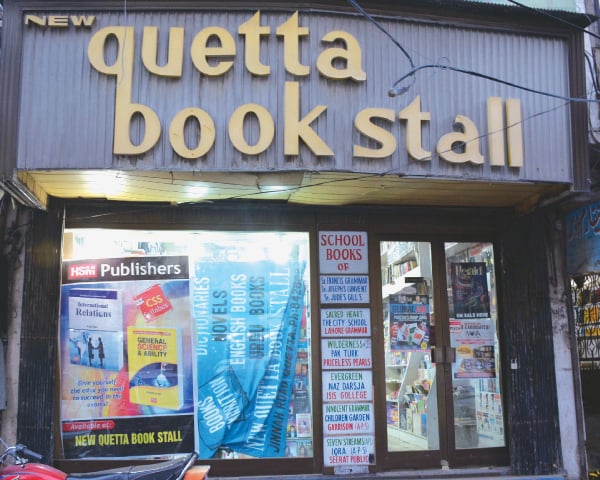

Successive governments remained unable to rein in sectarianism or destroy these shops. They were routed by General Pervez Musharraf and thereafter bookshops selling sectarian literature no longer existed in Quetta.

But the two decades or so that jihadi literature maintained a hold over Balochistan inflicted great damage to the fabric of Baloch society. In various educational institutions, for example, propaganda replaced scholarship.

“A former chairman of the University of Balochistan’s Islamic Studies department dedicated one of his books to the Afghan Taliban,” narrates a lecturer at the varsity while requesting anonymity. “The book would be read as coursework in the Master’s programme of the department.”

Meanwhile, with government oversight falling lax after Gen Musharraf, jihadi bookshops re-emerged in Quetta to restart selling sectarian and hate-material. This state of affairs largely continued till the brutal attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar in 2014. In pursuance of the NAP, a crackdown against sectarian outfits followed in Quetta as well. Bookshops selling sectarian literature were subsequently pushed to go underground.

There are three key reasons why jihadi literature is popular in Quetta. First, one can get a jihadi booklet either free or at throwaway prices. In comparison, even public school course books cost money. Second, in Quetta, there is a great number of shops selling religious literature. Some of them also sell jihadi literature albeit in secrecy. Third, background interviews with senior academics and journalists suggest that banned outfits and religious groups have correspondents in every district of Balochistan, who sell or distribute jihadi literature onwards among the populace. Most of them operate with impunity. Quetta is no exception to this phenomenon.

Despite the recent crackdown on banned outfits and jihadi literature, it is still not hard to get hold of literature that promotes religious extremism — neither in Quetta nor elsewhere in the province.

This is one of the factors why religious extremism in Balochistan is increasing its hold, both ideologically and territorially. Unlike the past, however, Baloch literature is also gradually being coloured by religion. Ruzhn, a magazine in Balochi, now routinely discusses jihadist concerns. The reason: Balochistan has tremendously transformed religiously in recent years.

THE HAZARA SPLIT

The Hazaras even today constitute one of Balochistan’s most literate and educated communities. With hardly four bookshops selling general books in Quetta today, the community in 2012 found some relief when some of its members decided to establish a library by the name ‘Umeed Public Library.’

Situated near the mountains of Marriabad, Umeed Public Library is an oasis of learning. Arif Ali, the incharge of the library, says they have been running it voluntarily. Inside the library, a cabinet catches a visitor’s attention at first glance. There are hundreds of books filled in this cupboard. This collection was donated to the library by the mother of Irfan Ali Khudi, the renowned Hazara activist killed in a bomb blast in 2013.

“There are 600 registered members,” says Zulfiqar Ali, the librarian at Umeed Public Library. “When educational institutions are in session, our library gets thronged by students, who come here to read books mostly of their coursework.”

These days, attendance is thin at the library because students are on vacation. But the librarian promises that it’ll be full once educational institutions are back in session. “On Sundays, though, only children are allowed to come to the library. They read stories here, draw, and paint among other activities.”

According to Zulfiqar, their library boasts a collection of 5,000 books — all of which were donated by members of the Hazara community and range from left-wing literature to right-wing topics. For the librarian, more than any ideological bent, what is more important is for young people to read a variety of topics. “Our main focus is on how to develop an interest in reading books,” says Zulfiqar.

One student to have benefitted enormously by being a member at the library is Mehdi Hassan. “I hardly read general books because these are dry,” he laughs. “Except Dr Mubarak Ali’s books. I haven’t really read any other history books apart from his. I also love reading short stories penned by Manto.”

Mehdi says that his interest in reading novels developed when he’d watch drama serials on television. “The first novel I read was Khuda aur Mohabbat.” The library has merely patronised his passion for fiction.

Such stories pushed the library into organising regular workshops for youngsters to interact with writers, journalists, and poets. The efforts bore fruit as students from the Hazara community began taking greater interest in book reading. “A case in point is a recent bookstall set up at the Hazara Society Hall, where in two days, the Hazara community bought books worth 7, 000 rupees,” argues Zulfiqar.

But while Umeed Public Library is an outpost of hope, sectarian ideas and literature have also permeated among the Hazara and a section of Hazara youth is getting radicalised. “Two political parties enjoy influence over the Hazara community in Quetta: The Hazara Democratic Party (HDP) and the Majlis Wahdatul Muslimeen (MWM),” notes Hasan Raza Changazi, a senior Urdu columnist and author based in Quetta. “The HDP is a liberal party while the MWM aims to unify the Shia throughout Pakistan.”

While the HDP is often described as a “liberal” party, it has a great existential tussle with the MWM. It not only accuses the MWM of being a “proxy” of the Iranian state but also alleges that their rivals are involved in “radicalising” Hazara youth by spreading sectarian literature. Quetta-based security analysts warn that the MWM is ideologically gaining foothold in the Hazara-dominated localities of the city. Many also fear the consequences of Sunni militancy and Shia militancy standing face-to-face.

MARX & MANDELA IN MAKRAN

On January 13, 2014, the Frontier Corps (FC) raided a book fair that was organised at Atta Shad Degree College, Turbat. Later on, Lieutenant Colonel Muhammad Azam of the FC while talking to the media claimed to have seized “anti-Pakistan” literature, books, maps, posters, banners and other subversive material.

The “anti-Pakistan” material the FC officer spoke of turned out to be literature penned by Karl Marx and Bertrand Russell as well as the biographies of Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Nelson Mandela and Che Guevara. Other literature recovered was history books written from a Baloch nationalist lens, including one authored by Mir Gul Khan Nasir, the most famous poet and scholar of Balochistan who died in 1983. Literary magazines including Mahtak Balochi, Sangar, Zrumbish and others were also seized.

In April that year, similar raids were carried out by the police in Gwadar, in which two shopkeepers were arrested. On January 3, 2015, more raids were conducted in Turbat albeit under the auspices of the NAP. The purpose of the security agencies was the same: to confiscate any literature deemed to be dangerous to state interests.

Turbat, the headquarters of district Kech, has been particularly problematic for security forces due to the popularity of ideas that are considered to be seditious or subversive by the state. As explained earlier, Turbat is also the historical home of Baloch separatism — both peaceful and militant. A strict check on what is being read is always maintained in order to stem these ideas.

Although the public education system is largely in the doldrums in the Makran belt (as it is elsewhere in Balochistan), Turbat got its first public university in 2012. The University of Turbat is only the second university in the province — that it was constructed 65 years after Partition tells a story of its own. Institutions such as the Atta Shad Degree College, for example, are now in the process of getting affiliated with the varsity.

But the Pakistani state has largely been unable to institute its narratives in the Makran belt, in part because many have access to the English language as well as to Balochi literature. English in particular is cause for concern among a segment of security forces, who believe with some justification that knowledge of the English language will push students towards the kinds of literature the state does not want them to read.

“Just before I was graduating from college, I was at a gathering with leftist politicians and progressive literature lovers,” narrates one nationalist activist. “At the beginning, it was embarrassing for me since I had hardly read any books. One of my senior colleagues then suggested I start my reading journey with [former communist leader and intellectual] Sibte Hassan. I really liked his books Maazi Kay Mazaar and Musa Se Marx Tak.”

Having started with Sibte Hasan’s books, the activist soon diversified his reading choices. He’d go on to read the primary works of Marx, Engels, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr, Nelson Mandela, Jean Paul Sartre, and Paulo Freire among a host of others. “Reading these writers is very interesting because they teach you how to think rather than what to think,” he argues. “It is somewhat like having a conversation with the great minds of their times.”

Like this activist, others in Turbat too often start off with a writer of their choice before diversifying their interests. But while 2009-2011 saw a great revival of a culture of reading ideas (based on the vibrancy of Baloch students politics in educational institutions), the recent past has once again witnessed a crackdown on private centres teaching English. On January 8, 2014, the FC raided an English language teaching centre in Turbat on the pretext that it was teaching “anti-Pakistan literature.” The centre was subsequently shut down.

One centre that has stood strong despite all that is happening around them is the Delta Language Centre. Established in 2006, one of its primary motives according to its founder, renowned educationist Barket Ismail Baloch, is reading and engaging with the wider world.

“After Quetta, Turbat is the only city where Dawn is widely read by students,” explains Barkat Ismail. “There are daily 50 subscribers to Dawn at my Delta Language Centre but readership increases to 100 on Saturdays and Sundays.”

With public schools largely in disarray in Turbat, access to the English language is a game-changer for many students. Duresham Karim Baloch, studying in class IX at one of the Delta centres, describes how she was introduced to Khalil Gibran’s book The Broken Wings in class VII. Reading habits cultivated back then have stayed with Duresham ever since.

But in various background interviews, it becomes clear that higher literacy in Turbat despite a public education system in disarray is because the city refuses to accept one idea or another as gospel truth. Diversity of thought also exists because official literature propounding the victories of warriors such as Mohammad bin Qasim or Mehmood of Ghazni is at odds with the rich oral traditions in Balochi, where indigenous heritage is given more weight than the culture brought along with foreign invaders.

“The first poetry that was actually penned in Balochi was in the 15th century, by Hammal Kalmati in Makran,” explains Hamid Ali Baloch, chairperson of the Balochi Department at the University of Balochistan. “The tradition of oral Balochi literature dates back to 1440.”

The professor explains that the era of written Balochi literature starts in 1838. It was only in the 1950s that Makran progressed to modern literature writing. “A group of writers were the trailblazers,” says Hamid Ali. “Syed Zahoor Shah Hashmi from Gwadar, Karim Dashti from Dasht, who is said to be mentor of Syed Zahoor Shah Hashmi, and Yar Mohammad from Makran too.”

This encouraged others to turn to the pen. For example, the great poet Atta Shad was inspired by the afore-mentioned wave of the 1950s and he in turn inspired another group of youngsters with an extraordinary interest in poetry and literature. From the 1970s to 1990s, Balochi poetry in Makran was as popular as Urdu poetry was in the rest of the country.

“In the past, academies were not established in Makran because the hub of literary activities used to be Karachi,” explains Hamid Ali. “Lyari, the Baloch-dominated locality in Karachi, was home to magazines published in Balochi on language, literature, and poetry.”

This association seemed to have weakened with political changes in Karachi as well as in Balochistan. As Lyari distanced itself from the murky politics in Balochistan, various academies sprouted in Makran to fill the literary vacuum. It is safe to say that Makran’s contribution to Balochi literature has been second only to Sindh. In fact, Balochi literature produced in the Makran belt now better reflects their political realities in their particular scenarios.

JIHAD IN THE NORTH?

The construction of jihadist thought in northern Balochistan is widely believed to be an outcome of large swathes of Pakhtun populations living there. The argument is that Pakhtun people are conservative by nature and therefore, right-wing ideas have greater appeal in the Pakhtun belt.

But Barkat Shah Kakar, a teacher at the Pashto Department of the University of Balochistan, argues that this construction is artificial. “It is deliberately shown that Pakhtun society is religious but that is not the case in reality,” contends Barkat Shah. “To this day, discussion of nationalistic ideas is dominant among the Pakhtun population in Balochistan.”

For the Pashto professor, the seeds of extremist thought in Balochistan were sown even before Partition. “In undivided India, more than 100 people from our northern belt went to Deoband to study religion. When one of them would return, he’d erect a madressah and get his disciples,” explains Barkat Shah. “In this way, religious thought expanded slowly and gradually. From here, Maulana Abdul Haq, Maulana Mohammad Hassan, among others, went to Deoband for religious studies. Religious education was already present [in the region] but it was not as institutionalised in the beginning as it is today.”

Modern literature, in its written form, arrived in Balochistan’s Pakhtun belt with people who were attached with Persian and Arabic. These included religious ulema who were teaching in madressahs and mosques. “They are your first poets, calligraphers, and even their poetry reflects a religious flavour,” explains the professor.

In the 20th century, he explains, the first short story was penned in Pashto literature. It was titled The Virgin Widow. From the 1920s to the 1930s, literature produced in Pashto had a dominant “reformist” element. Before and after Partition, Pakhtun intellectuals such as Abdul Samad Khan Achakzai, Sain Kamal Khan Sherani, and Ayub Khan Achakzai among others were all considered “anti-imperialist.” These men were progressives who had a pivotal role to play in Pashto literature, language, and politics.

“But while leftist literature was produced a lot in the Pakhtun belt, the problem is that those who produced progressive literature did not associate with the mainstream left despite the fact that their work is progressive,” asserts Barkat Shah.

“Right-wing literature has a fixed and limited readership but it does enjoy patronage from some quarters,” argues the professor. “In Pashto, you can find around half a dozen magazines which enjoy such support that they can be handed out for free. It is somewhat like creating an artificial need.”

CAN THE STATE REBOUND?

Plurality of thought and the healthy debate it generates is central to a vibrant, functioning democracy. But in a place where as columnist Cyril Almeida puts it, “murky things happen for murky reasons,” thought in Balochistan is policed by various quarters. Various ideologies are already considered suspect and therefore, no constructive debate or discussion tends to happen.

Nevertheless, one of the key reasons behind the current state of affairs is governmental apathy in the matters of education, literacy and the production of literature. In the vacuum left by the government, others vie for greater influence.

“Hate speech and material have starting appearing on the internet which the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) should take notice of and prosecute under the cyber crime bill,” says CCPO Cheema. “Since hate-mongers on ground are afraid of selling and propagating jihadi materials, they find it easier to propagate their agenda on the internet. They propagate and distribute hate material very secretly.”

Academics argue that sectarian outfits were given a free hand in Balochistan to undercut the influence of Baloch nationalists, particularly those arguing separation from Pakistan. Although sectarian outfits have recently been reined in, their propaganda continues to spread far and wide. Such are the challenges being faced by the Balochistan governmental machinery on the ground.

But there are other institutional problems too — mistrust of anything in English or Balochi being the foremost of these. While Urdu is the country’s national language, Balochi does not enjoy much cultural capital within governance structures. The heroes of Balochi literature, for example, are not the heroes of official literature printed in Urdu. In Urdu literature, these same Baloch heroes are described as trouble-makers and unpatriotic.

Similarly, religious literature in Urdu is widely read in the central and eastern parts of Balochistan. Interestingly, Balochi writers and readers are predominantly based in Makran but their audience is also largely Makran-based. Even Panjgur, one of the districts of Makran, is comparatively religious in nature. Co-education and private schools were closed down in recent years by religious extremists over there. The situation now is that there are a few magazines in Balochi which solely discuss religious affairs.

These dichotomies and the inability of various political stakeholders to resolve them have left knowledge production in great danger in Balochistan. The ultimate losers of this status quo are Baloch citizens particularly the newer generations — differentiating between fact and propaganda is not something they ought to have been burdened with but it is still a burden they are forced to carry.

*Identity changed to protect privacy

The writer is a member of staff.

He tweets @Akbar_Notezai

Published in Dawn, EOS, April 16th, 2017