Cola wars: A social and political history

‘Cola Wars’ is a term which emerged in the US in the early 1980s. It was coined to describe the advertising and marketing tactics of The Coca-Cola Company and PepsiCo against each other.

Coca-Cola has been the dominant cola in a majority of countries, followed by Pepsi. Both have continued to place their respective communication on positions initially formed during their respective inceptions.

For example, Coke’s advertising has traditionally focused on wholesomeness, nostalgia and the family as a nourishing unit.

Pepsi on the other hand, has been positioning itself as a youthful brand that keeps up with the aesthetic and social shifts which take place with the emergence of every new generation of young people.

Coca-Cola was first introduced in 1886 in the US. Its original recipe included cocoa leaves and a small amount of cocaine. Its early advertising claimed that the cola cured headaches and gave the consumer a ‘slight buzz.’ It was described as a ‘brain and nerve tonic.’

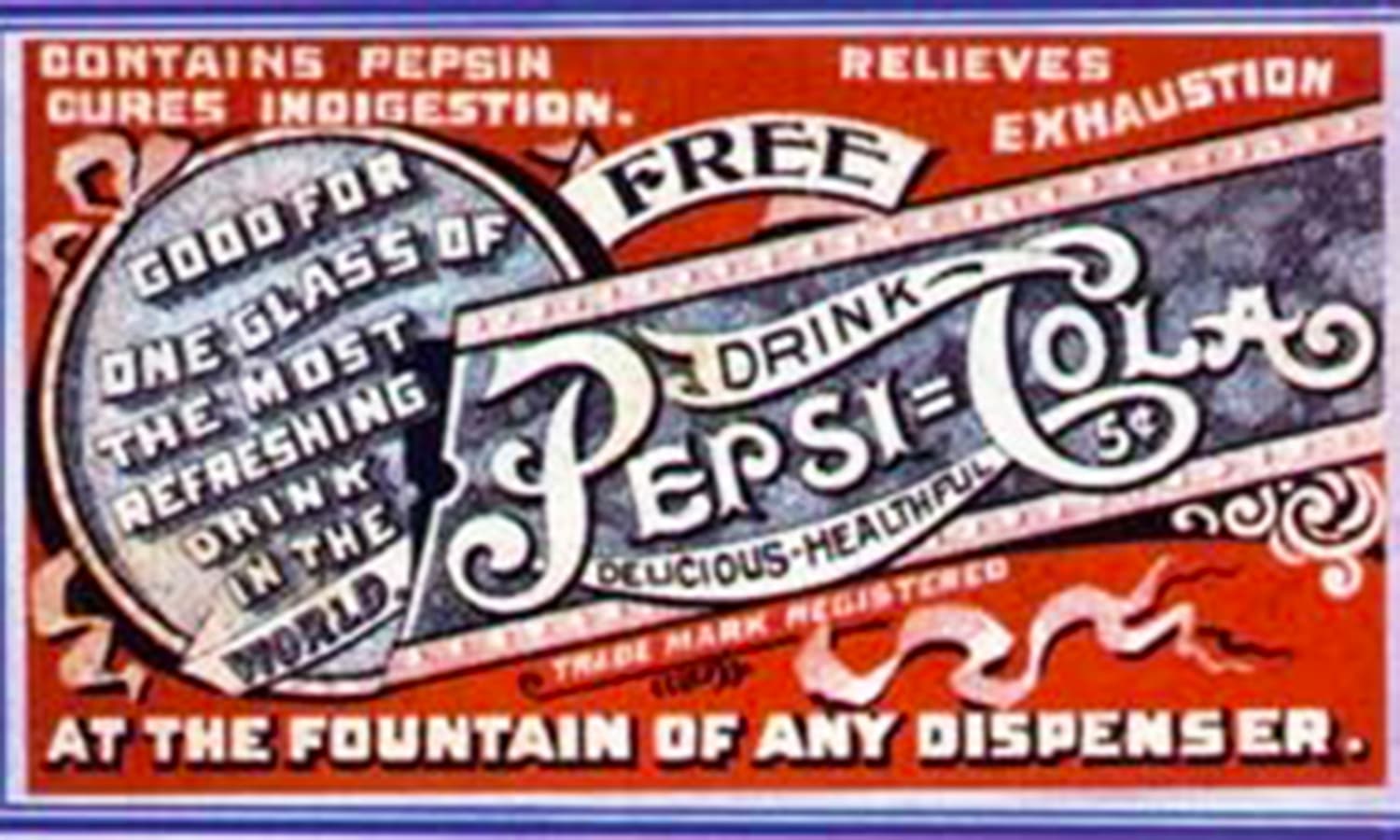

Pepsi arrived seven years later in 1893. Its recipe contained a digestive enzyme called pepsin and kola nuts. Early Pepsi ads claimed that it cured indigestion and was ‘healthful.’

In the early 1900s, when alcoholism started to emerge as a serious problem in the US and various social groups began demanding a ban on alcoholic beverages, Coca-Cola decided to side with the anti-alcohol lobby (the ‘Temperance movement’).

Consequently, in 1903, Coca-Cola removed cocaine from its formula, substituting it with caffeine. It then positioned itself as ‘The Great National Temperance Beverage.’

1915: As Coca-Cola continued to build on its wholesome image and America’s largest-selling cola, Pepsi tried to stay in the race by keeping its price low and offering more cola in bigger bottles. It also began to offer straws (a new invention) with every bottle of Pepsi.

Boom: During the height of an economic boom in the US in the 1920s when fortunes were being made and the American president had declared that ‘America’s business was business,’ Coca-Cola celebrated the zeitgeist of the period by announcing its own success with this ad.

Bust: The good times came to an abrupt end when in 1929, the US economy buckled. An unprecedented economic depression left many businesses bankrupt and millions of Americans unemployed. In 1931, Pepsi filed for bankruptcy.

1935: Coca-Cola survived the crash and continued to play on its wholesome image. Across the 1930s, it encouraged people to ‘take a pause’ and enjoy (with a Coke) moments associated with the ‘American way of life’.

In 1934, Pepsi returned from bankruptcy, reminding people what it was, in case they had forgotten.

1939: During World War II, Coke set up a bottling and manufacturing plant in Germany, which at the time was under Nazi rule. Coke’s other drink, Fanta, was formulated here.

1942: During World War: II, Coca-Cola ran a series of ads which expressed Coca-Cola as a patriotic brand which greeted Americans wherever they went, ‘reminding them of home’.

During World War: II, Pepsi claimed it provided energy to the American war effort (because it had more calories).

In 1947, Pepsi broke the taboo of directly addressing to and showing Black Americans in it ads. Black Americans were still called Negros and hardly had any political or civil rights.

The ploy of marketing to the blacks was scorned at in the Southern segregation states of the US where Pepsi was threatened by racist groups. However, Pepsi managed to greatly increase its sales among blacks in the South.

In the early 1950s, as the US economy began to recover, Coca-Cola offered itself as the taste of tranquility and prosperity. And it also introduced itself as ‘Coke’ for the first time.

In the 1950s, whereas Coke went looking for the romance of the decade’s prosperity, Pepsi defined the same as something which was more youthful.

In 1955 Coke used black Americans for the first time in their ads.

Very white in the South. Pepsi continued to cater to the niche black market. However, to address the disapproval this ploy was experiencing in the Southern states, Pepsi ran a separate campaign in which it claimed that Pepsi was part of Southern Goodness.

The first Coca-Cola plant in Pakistan went up in 1953.

Pepsi hired American Vice-President, Richard Nixon (second-left), as its international brand ambassador. Pepsi had asked him to somehow get the Soviet Communist leader, Nikita Khrushchev (first-left), to take a sip of Pepsi. Nixon managed to make Khrushchev take a sip during Nixon’s 1959 visit to Moscow. Pepsi flaunted the photo of the occasion as a marketing coup: making a communist taste Pepsi.

Pepsi entered the Pakistan market in 1959.

The 1960s were a turbulent decade. A rebellious disposition began to form among the youth against the conformity of the 1950s.

Coke’s traditionalist image made it tough for the brand to convincingly incorporate the radical trends of the decade.

So it addressed concerns arising from the turbulence of the era by reassuring people that things would get better.

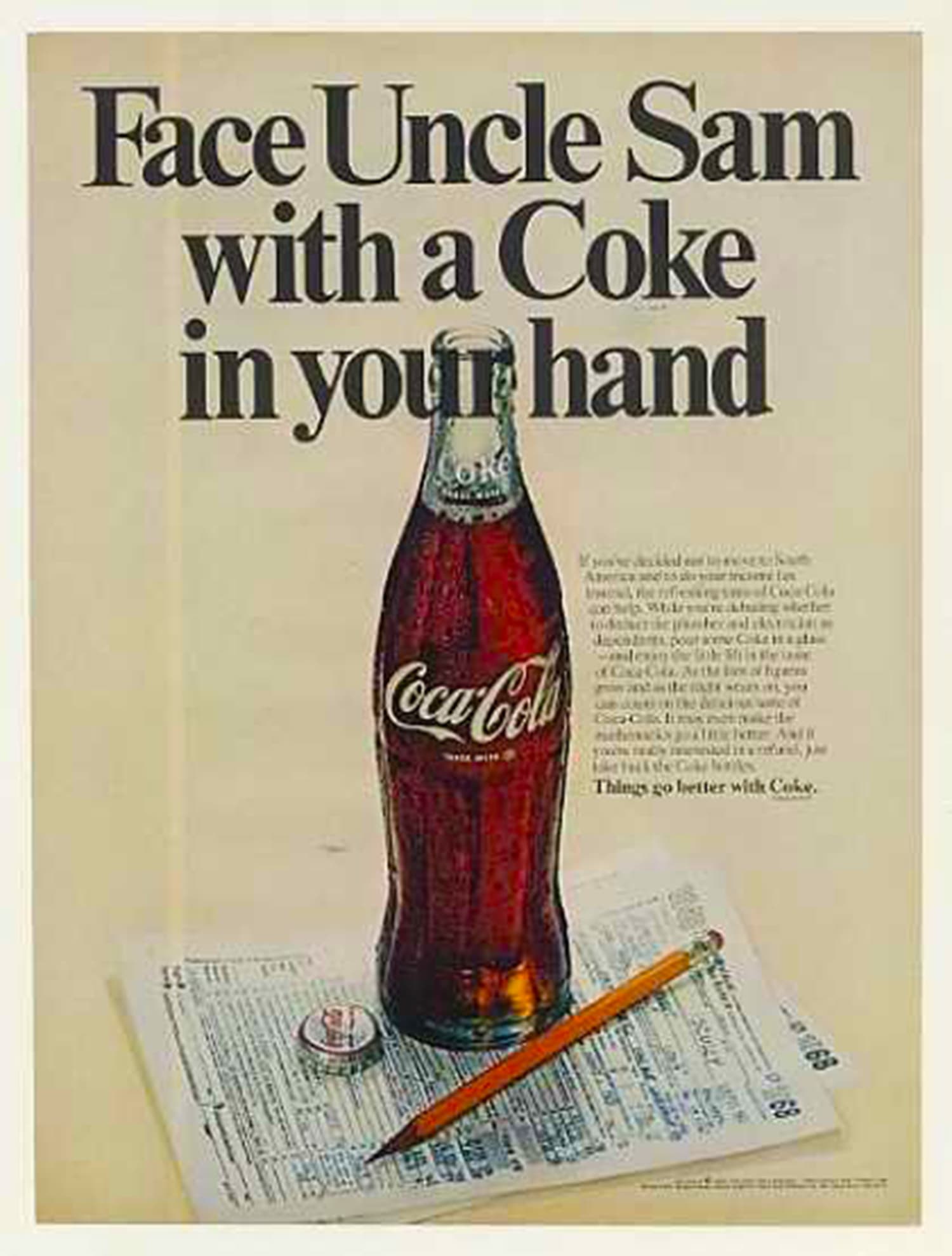

Coke stood for this across the 1960s: A brand which made ‘things go better.’

1961: For Pepsi, however, the radical change of the 1960s proved to be a branding boom. Pepsi’s communication and marketing ploys started to squarely address young people with the slogan, ‘Now it’s Pepsi for those who think young.’

In 1963 Pepsi exited from Pakistan due to dipping profits.

In 1965, when the media began to define the young people of the era as part of a more willful generation (the We Generation), Pepsi claimed ownership of this generation. It called it the Pepsi Generation.

When Richard Nixon became President in 1969, he replaced Coke with Pepsi as the official drink of the White House.

1969: When the late 1960s became marred by student violence and protests all over the world, and when America’s war in Vietnam became more brutal, surprisingly it was Coke which directly addressed the phenomenon.

In a one-off ad it asked young protesters to argue their point of view in a cooler manner.

Coke first came up with its most famous line, ‘it’s the real thing’ in 1969.

In 1972, inspired by the emergence of many New Age spiritual trends and movements of the era, especially the Peace Movement, a Coke TV commercial highlighted the growing multicultural nature of the American society and of the world.

The ad became a massive hit and its jingle ‘I’d like to teach the world to sing’ actually became a pop hit.

Pepsi entered the Soviet Union in 1972. It is believed so did Coke, but the entry was not recognised by the US government. However, Coke made its 'official entry' there in 1979 by selling the company's orange drink, Fanta.

Pepsi was the leading cola in Chile. In 1973, a US-backed military coup ousted an elected socialist government. Later it transpired that when the socialist government was formed in 1970, Pepsi Co. along with a few other major US companies in Chile, had exhibited their concern to US Secretary of State, Hennery Kissinger, hinting for US intervention.

1973: Due to an economic recession setting in the early 1970s; and the rupturing of the utopian spirit of the 1960s’ We Generation, individuals became more self-seeking.

According to sociologist Tom Wolfe, the We Generation had now given way to the Me Generation.

Pepsi responded to the shift by celebrating the desires and dreams of the individual alone (the ‘you’).

In the late 1970s, Coke exited from India due to tough foreign exchange regulations.

Pepsi had not yet been launched in India, and Coke’s departure saw the emergence of a similar local drink, Thumbs-Up.

Pepsi adopted the famous bumper sticker of the 1970s, ‘Have a Nice Day.’ In 1975, it altered it to ‘Have a Pepsi Day.’

In 1975, when American troops hastily abandoned the war in Vietnam and the country was reeling from the impact of a President (Nixon) resigning to escape impeachment, Coke asked Americans to transcend despondency and ‘look up.’

1977: The ‘Cola War’ came out in the open when a marketing ploy by Pepsi called the Pepsi Challenge in which Pepsi representatives set up tables in public places with two white cups, one containing Pepsi Cola and the other Coke.

People were offered to sip from both the cups and decide which one tasted better. Results showed that most people preferred Pepsi.

The campaign was stretched into the 1980s and Pepsi began to successfully win over fans of Coke purely through the perception that was created by the results of the Pepsi Challenge campaign.

When Democratic Party’s Jimmy Carter became President in 1977, he replaced all Pepsi vending machines in the Whitehouse with Coke machines.

By now Coke had become associated with the Democratic Party, and Pepsi with the Republican Party. This was ironic because Coke’s brand philosophy was conservative compared to that of Pepsi’s.

Pepsi re-entered the Pakistan market in 1979 with its famous skateboarding TV commercial which was translated into Urdu.

1980: Pepsi goes yuppie. The feel-good self-absorption of the 1970s’ Me Generation, evolved into a generation that now strived to gratify its ego by acquiring material wealth.

This generation was labeled as the Gimme Generation. The 1980s’ Gimme Generation shaped the Yuppies (or upwardly mobile young people).

Come 1980 and Pepsi was now talking to the Gimme Generation. Its slogan for the early 1980s became: ‘Pepsi’s Got Your Taste For Life’.

The good life: Coke wasn’t all that far behind. In 1982 it informed that Bacardi rum tastes best with Coke.

Cover of the May 1985 TIME magazine. From having a market share of over 60 percent in the US, Coke’s share plummeted to just 23 percent in 1983.

The company went into a panic. As a desperate reaction, in 1985, Coke reformulated its original recipe and introduced the New Coke. It was a disaster.

People were soon seen emptying bottles of the New Coke in the streets. Pepsi took out a full page ad in the New York Times which declared that Pepsi had won the Cola War.

1985: Front page report on the return of the old Coke. Within three months, Coke brought back the original Coke as Coca-Cola Classic. Ironically, Coke’s rash reaction and the way the war got played out in the media, actually ended up giving Coke the momentum which the brand’s executives and advertising agencies had failed to generate from 1976 onward.

After the arrival of Coca-Cola Classic (or the old Coke), Coke sales which had begun to dip, rose dramatically.

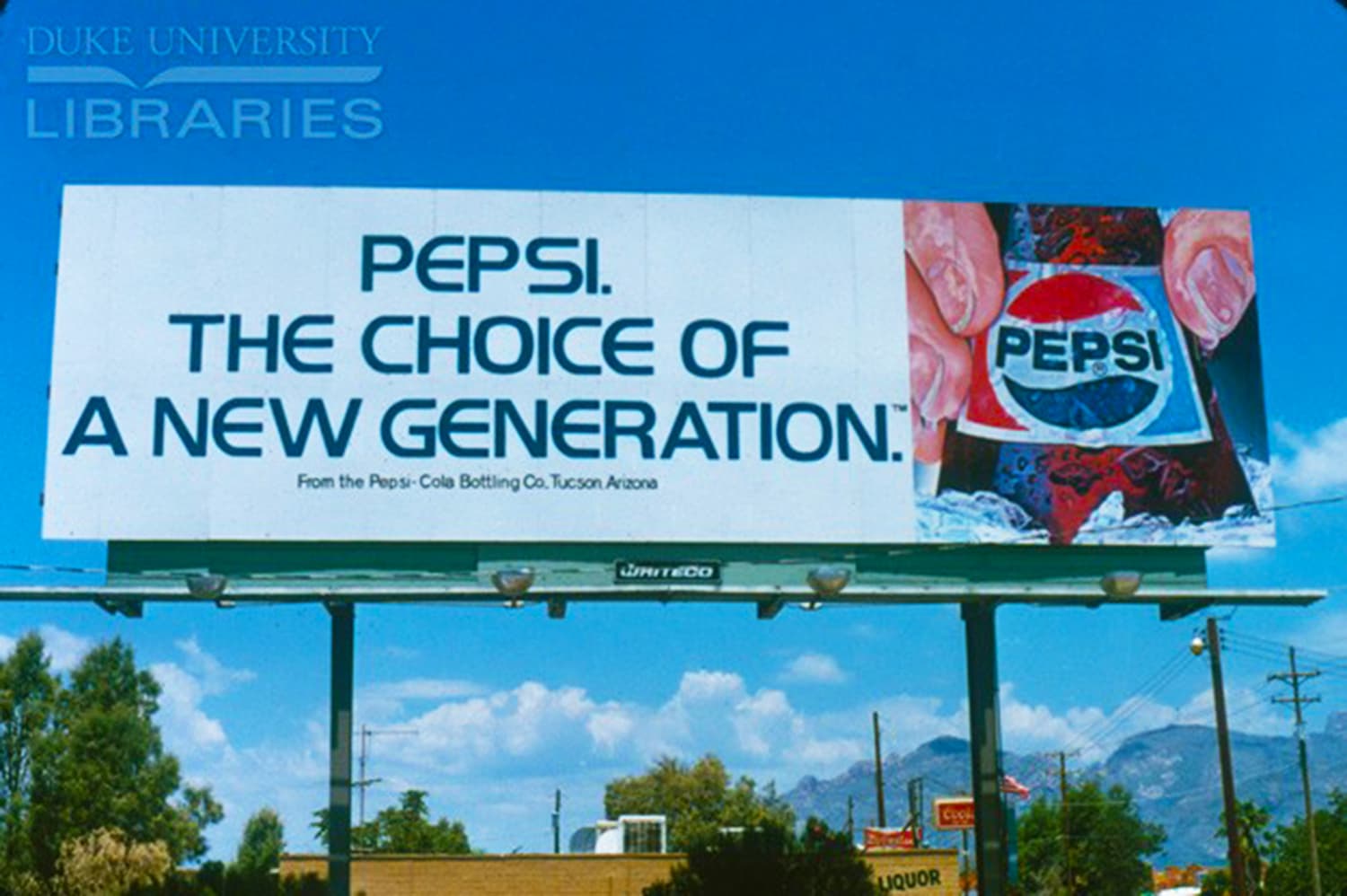

The Gimme Generation started to generate its own brand of culture (based on self-seeking pursuits).

And since the Gimme Generation enjoyed the concept of having various choices in life, Pepsi now became Choice of a New Generation.

Pepsi hired Michael Jackson as brand ambassador after his 1984 album, Thriller, went multiplatinum.

In 1987, Pepsi signed up famous Pakistani cricketer, Imran Khan. By then Pepsi had overtaken Coke as the leading Cola brand in Pakistan.

Due to India’s new deregulation policies, Coke returned to the country in 1993. At the same time Pepsi made its debut in India.

The late 1980s started witnessing a backlash of sorts against the ethos of the Gimme Generation, and in response, the 1990s became a decade in which more embracing concepts such as multiculturalism began to take hold.

The new generation would go on to be called Generation X. Pepsi labeled it Generation Next.

Anticipating the shift in the1990s, Coke rekindled its 1960s slogan, The Real Thing, suggesting that Coke was still the original cola.

Apart from investing heavily in cricketing stars, Pepsi in Pakistan also started to sign up local pop acts which emerged in the late-1980s/1990s. Pepsi managed to bag 62 percent of the cola market in the country.

Though Coke had been associated with the Olympics for decades, in India and Pakistan it, for the first time, it became a sponsor of a major sporting event. It was the official drink of the 1996 Cricket World Cup held in India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

In the 2000s, young people had become more informed thanks to the advent of the internet. With the expansion of social media, the new generation also became a lot more opinionated. Sociologists called this generation, Generation Y (the Millennials).

Being more tech-savvy, Generation Y was also a lot more demanding compared to the more introverted and cynical Generation X of the 1990s.

'Want More' became the central notion of the new generation’s ethos, which was growing up in an age where technology was challenging all kinds of social and technological limits.

Pepsi’s slogan in the early 2000s attempted to encapsulate the cultural dynamics of Generation Y with the slogan: Dare for more.

Coke refreshed its appeal in the 2000s to attract the attention of Generation Y. It tried to capture the concept of happiness in the more diverse and multi-cultural disposition of the Millennials.

Since the 1960s, Coke had been associated with the Democratic Party and Pepsi with the Republican Party.

However, the 2008 US Presidential election witnessed a switch, with Pepsi endorsing Democratic Party’s Barack Obama and Coke backing the Republican candidate, John McCain.

In Pakistan, where ever since the late 1980s, Pepsi had greatly cornered the cola market, Coke began to hit back from 2010 onward. It put Pepsi under pressure for the first time in decades.

When Pepsi abandoned local pop music in the early 2000s (sticking only to cricket), Coke filled the vacuum with Coke Studio – a show which became a massive hit in the region.

In a reversal of fortunes, for the first time in many years in Pakistan, Coke became a trendsetter and Pepsi, the follower.

In 2017, a Pepsi ad showing a demonstrator offering a Pepsi can to a cop was widely criticised. It was seen as trivialising activism. It was pulled off the air.

Getting a tad carried away by its new-found trendsetting status in Pakistan, a Coke campaign suggested that people should replace tea-drinking with Coke! Since Pakistan is a huge tea-drinking nation, the idea was widely ridiculed and mocked.