Much has been said about what the lynching of Mashal Khan revealed about Pakistani society – from the brutal consequences of mob hysteria to the degree to which fanaticism has seeped into the social fabric.

That the tragedy took place in a university, however, spoke to another process that has helped bring the country to its current impasse – the political and ideological brutalisation of its students by the state.

The on-campus lynching of a student by a mob of his peers solely on the basis of his progressive ideas was chilling to all who witnessed it; yet it was also simply the logical culmination of a decades-old state project to neutralise the potential of student politics for resistance and dissent in Pakistan.

This project has largely been successful. Today, with the exception of a few campuses, the Pakistani university is not a space of freedom for learning, ideological debate or critical thinking, but one of apathy, ideological conformity, and moral conservatism, often enforced through a nexus between the state, university administrations and unelected right-wing student groups.

Also read: At Pakistani universities, fear rules supreme on Valentine's Day

The Pakistani university has become a space of institutionalised apathy, where students can be arrested with impunity for celebrating Sindhi culture; where they can be attacked by rightwing vigilantes for performing Pakhtun dance or for talking to a member of the opposite sex; where they can get killed for playing music; and where bright, progressive young men can be mercilessly lynched simply for imagining a less bigoted and unequal society.

An interrupted legacy

How did it come to this? Such poverty of political imagination among students was not always the norm. From the 1950s to the 1980s, Pakistani students were not a rag-tag mob but a collective, organised force to be reckoned with. They stood up to exclusionary education policies, organised strikes in support of organised labour and formed the core of the movement that brought down the dictatorship of Ayub Khan in 1969.

Campuses in the 60s and 70s were rife with healthy ideological contestation between Left and Right, with progressive groups like the Democratic Students Federation (DSF) and National Students Federation (NSF) often electorally ascendant over their right-wing counterparts.

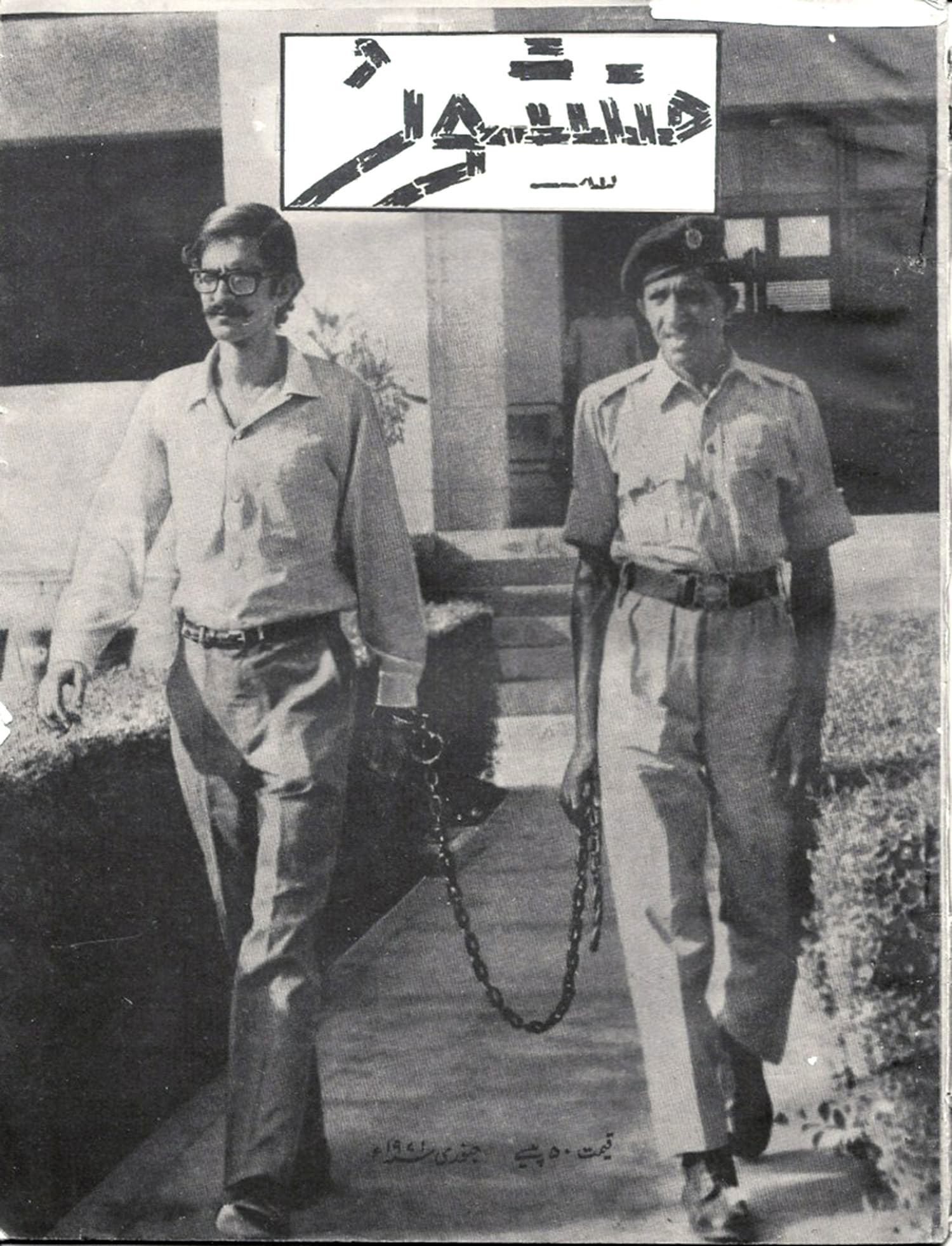

Explore further: I was handcuffed and tied but it was worth my fight against One Unit

At the zenith of student politics in the 1970s, student power could be gauged from the presence of union representatives in all university decision-making bodies through legislation that mandated student consent for university policies.

Some student radicals even got elected to Parliament, like the NSF socialist Mairaj Muhammad Khan, who won on a PPP ticket from Karachi and became Labor Minister under Bhutto in 1971 (eventually resigning after 2 years once Bhutto began to renege on his socialist pledges).

Things changed drastically of course under Zia. As an autocrat opposed to the very idea of popular democratic participation itself, Zia saw student unions, dominated as they were by the Left, as a nuisance that required a permanent solution.

His regime began by arming right-wing groups like the Islami Jamiat Taleba (IJT) in 1979, which started conducting armed assaults on progressive student leaders in major universities, fueled by the anti-communist hysteria of the Afghan War.

When this failed to stop the progressive fightback, in 1984, soon after the country-wide electoral rout of the IJT by the student Left in union elections, student unions were permanently banned by the military regime.

Predictably, the regime cited campus violence – that it had itself initiated and facilitated – as the basis for the ban. The actual reason of course was Zia’s fear of the risk posed by a young, well-organised constituency that had publicly committed itself to his downfall.

Zia’s ban – briefly removed by Benazir but ultimately reinstated by the then deeply conservative and compromised Supreme Court in 1993 – was more successful than he could have imagined. It fundamentally transformed both popular student culture as well as progressive politics, which relied heavily on student cadres in its mass organising efforts.

Over time, campus character mutated from the ethos of politico-ideological resistance of the 70s to the puritanical right-wing conformism of today. From once being a bulwark against military dictatorship and religious extremism, the majority of Pakistani students transformed into unthinking imitators of state ideology – formally disengaged from politics but channeling the dominant religio-nationalist discourse through both their actions and inertia.

The purge of progressives

Campus politics did not disappear altogether after the ban but, over time, gradually degenerated to a shadow of its former self. Unions had allowed students a reasonable amount of collective power – they were institutionally recognised as collective bargaining agents by universities and could negotiate student concerns from fees to accommodation to broader policies that affected them.

They had also allowed a recognised space for ideological debate and non-violent electoral competition, which meant students from varied ethno-linguistic and religious backgrounds could form coalitions around common ideas – as they did in the diverse array of independent student organisations that existed.

When this space was snatched away, the ties that it facilitated for students across ethnic and religious lines also withered. The basis for the informal student politics that remained gradually became reduced to the lowest common denominators – those of ethnicity, religion or sect.

In depth: Mob mentality: How many hands is Mashal's blood on?

While progressive groups were violently persecuted under the ban’s cover, student organisations under the patronage of the military or ruling parties – such as the IJT or the Muslim Students Federation – were allowed to operate.

A steady stream of funds and arms enabled such organisations to continue functioning informally, reinforced by the state where necessary (particularly in the smaller provinces), to eliminate any remaining progressive resistance on campuses.

Without formal, elected organisational structures and legitimate collective authority, student organisations turned into personal mafia-like fiefdoms, sustained by distributing patronage – in the form of hostel space, university admissions or physical protection – and establishing their authority through the exercise of brute force, mirroring the clientelism logic of the state and ruling parties.

Over time, groups like the IJT helped realise what the state had set out to do – wipe out progressive campus politics while ingraining a popular suspicion of the very idea of student politics in the wider social consciousness.

With institutional student politics now a distant memory, the idea of student unions came to be synonymised with the violent thuggery of groups like the IJT. It was, in part, this embedded perception of the illegitimacy of student activism that allowed Abdul Wali Khan University (AWKU) to demonise Mashal as a blasphemer simply for raising legitimate concerns about financial corruption on campus.

Engendering retrogression

Of course, the union ban and its prejudicial implementation did not, by itself, achieve the state’s objectives. It was accompanied by Zia’s manipulation of the education system through policies that sought to induce in students a ‘loyalty to Islam and Pakistan’ and ‘a living consciousness of their ideological identity’.

The social and natural sciences came under particular attack in universities, as anti-communist and anti-science propaganda funded by Saudi petrodollars came to replace critical scientific inquiry.

Ideological conformism on campuses was reinforced by hounding out leftist teachers, replacing them with conservative hardliners, and introducing retrogressive content into the curriculum that demonised religious minorities, vilified critical thinkers, glorified war, and erased popular movements.

On the same topic: Promoting anti-science via textbooks

This legacy of thought control did not die with Zia – as recently as 2014, the Higher Education Commission issued a circular prohibiting educational content that ‘challenged the ideology of Pakistan’ in universities.

It was this same anti-progressive venom that reared its head in AWKU, evidenced by one of Mashal’s professors reportedly declaring at a faculty meeting that the university ‘did not need communists on campus’ even as the leftist student was being hunted by the mob.

As is now evident, the impact of this curricular propaganda on students’ ideological worldviews has been deeply damaging. Instead of being equipped with the analytical means to understand and critically engage with their surroundings, most students have been conditioned to think of complex natural, social, economic and political phenomena in black and white terms – and to conceive of most social contradictions as requiring simplistic moral, technical – and often violent – solutions.

This conservative shift in student opinions has been well-documented. A study by scholar Ayesha Siddiqa found that majority of Pakistani students were suspicious of the democratic process, supported the military’s role in politics, harboured nostalgia about a romanticised theocratic past, agreed with the Clash of Civilisations thesis, opposed a federalist decentralisation of power, and considered political parties to be ‘inherently corrupt’.

Concerns about students’ own rights and collective well-being did not rank highly among student priorities; especially ironic in an era where students have suffered from breakneck educational privatisation and skyrocketing costs, plummeting public standards, on-campus repression by paramilitary forces and even murderous attacks by the Taliban.

A constrained renewal

In this historical context, Mashal Khan’s lynching represents the grisly depths to which student political culture has regressed. Yet, there have been some glimmers of hope amid the gloom in the past decade.

Several campuses rose up briefly against Musharraf’s 2007 emergency, a process that helped weaken the dictatorship and politicised a new generation of student activists, albeit a minority.

Sporadic protests have been generated by Pakhtun, Sindhi and Baloch students against the hegemony of fundamentalist groups in Punjab or state's high-handedness in Sindh. The Baloch Students Organisation (BSO) has continued its politics of resistance to atrocities in Balochistan, often in the face of brutal repression (including enforced student disappearances).

More recently, progressive student organisations of the past, including NSF and DSF, have also seen a revival, while new ones like the Democratic Students Alliance and the Progressive Students Collective have been formed to reorganise students and revive their alliances with workers and farmers.

However, the ban on unions continues to prevent these periodic expressions of progressive student action from coalescing into broader movements. The continued absence of both institutional legitimacy and inter-campus networks for student politics hinder generational continuity, coordinated action, and solidarity.

Unlike in 2016 in India, when thousands of student across dozens of Indian campuses demonstrated in solidarity with Jawaharlal Nehru University students facing a state backlash for questioning the dominant narrative on Kashmir, few Pakistani campuses rose in solidarity with LUMS students when they faced similar state censorship for attempting a dialogue on repression in Balochistan.

Towards redemption

Today, fascism is on the rise globally; yet from the United States to Greece to India and elsewhere, it is being met with stiff opposition whose ranks, more often than not, consist of thousands of progressive students.

In Pakistan on the other hand, the state has stunted the political imagination of the bulk of its students and snatched from them both the capacity to think critically and the mechanisms to act politically, such that they are either indifferent to or complicit in the rising fascist tide.

Reversing this decades-long generational rot will take time, but there are ways forward. In the first instance, this history must be popularised among students as a central component of the answer to why Pakistan has fallen prey to such violent radicalisation with such weak progressive resistance.

The destructive ban on unions has to be overturned. The decrepit curriculum that produces the poisonous bigotry that killed Mashal needs to be comprehensively overhauled. The armed thuggery of groups like the IJT and other vigilantes needs to be met with stern state action and the concerted de-militarisation of campuses.

But there is little evidence in the hollow words and actions of the ruling elite that they will willingly undertake these tasks. A pliant and conservative student body is far too convenient to their interests for them to realise that its character has jeopardised the very future of the country.

Ultimately, these tasks will have to be taken on by students themselves; those who recognise what the state has done and possess the will to become, like Mashal, the conscious agents of history that will help reverse the tide.

This article was first published in April 2017

Are you a student or teacher in Pakistan who wants to see progressive changes in universities? Tell us about it at blog@dawn.com