Sarfraz Ahmad made his ODI debut in 2007 at the age of 20. He had come into the side after leading the Pakistan U19 team to victory in the 2006 youth World Cup in Sri Lanka. The team’s opponents in the final of that event were India.

In 2007, Sarfraz was selected in the country’s national side during its tour of India as an understudy of Pakistan’s then regular wicketkeeper-batsman, Kamran Akmal. Sarfraz’s ODI debut was quiet. He hardly grabbed any catches and was not required to bat.

Born in Karachi into a middle-class Urdu-speaking family in 1987, Sarfraz, like most cricket enthusiasts in this city, began playing the sport in streets and alleys. From the streets, he eventually graduated to playing for various clubs.

Inspired by the exploits of Pakistan’s wicketkeeper-batsmen of the 1990s, Moin Khan and Rashid Latif, Sarfraz adopted wicket-keeping.

For some reason, Karachi has produced the most number of quality keepers. These include Wasim Bari (1967-83); Shahid Israr (1976); Taslim Arif (1979-81); Anil Dalpat (1984-95); Saleem Yousuf (1982-89); Moin Khan (1991-2002); Rashid Latif (1992-2003) and now Sarfraz Ahmad.

Many believe that cricketers from Karachi are always more innovative in their technique and thinking compared to those emerging from other parts of the country. This may be due to the way cricket is played in the narrow lanes and streets of this city. It creates an entombed and almost besieged cricketing mindset which demands innovative methods and thinking from the players.

As batsmen, they need to come up with unique strokes to navigate the limited gaps and spaces available to hit the ball in; and as bowlers and fielders, they, through tight lines and regular sledging and bantering, reinforce the entrapped feeling in the batsmen’s mind.

This mindset remains with those who manage to enter the city’s widespread club cricket scene and even when some of them rise further to play international cricket for Pakistan.

Karachi’s first batch of famous cricketers came from the same family: the Mohammad brothers – Hanif, Wazir, Mushtaq and Sadiq. Hanif had played much of his initial cricket as a child and teen in Junagadh, where he was born, in pre-Partition India.

So when he was selected for Pakistan after the country’s creation in 1947, he played with a straight bat and was the most conventional cricketer among the brothers. Same was the case with Wazir.

However, even though both Mushtaq and Sadiq were also born in Junagadh, they were much younger and started playing cricket on the streets of Karachi when the family moved from Junagadh to Pakistan. Mushtaq was arguably the first batsman to use the now-common reverse sweep. He pulled it out in a side game against the visiting Indian side in 1978. In his 2006 autobiography Inside Out, Mushtaq wrote that he had been playing the reverse sweep as a kid in Karachi.

It was also Mushtaq (as captain) who introduced the whole concept of sledging in the Pakistan team during its 1976-77 tour of Australia. In his book, he wrote that though the Australians invented sledging, he thought since Pakistani players (especially from Karachi) had grown up doing it all their lives, it was easy for them to counter Australian sledging by doing it in a more effective manner.

The most intriguing example of how street cricket in Karachi shapes many curious innovations is associated with Sadiq Mohammad, the dashing left-handed batsman who went on to become one of Pakistan’s most successful openers.

Sadiq was born right-handed but when as a kid he began to play cricket with his elder brothers on the streets, they forced him to bat left-handed by tying his right hand behind his back!

Mushtaq wrote that they did this because where they played, there were more scoring areas for a left-handed batsman and also the fact that there were not many left-handed batsmen in the city’s cricket scene at the time.

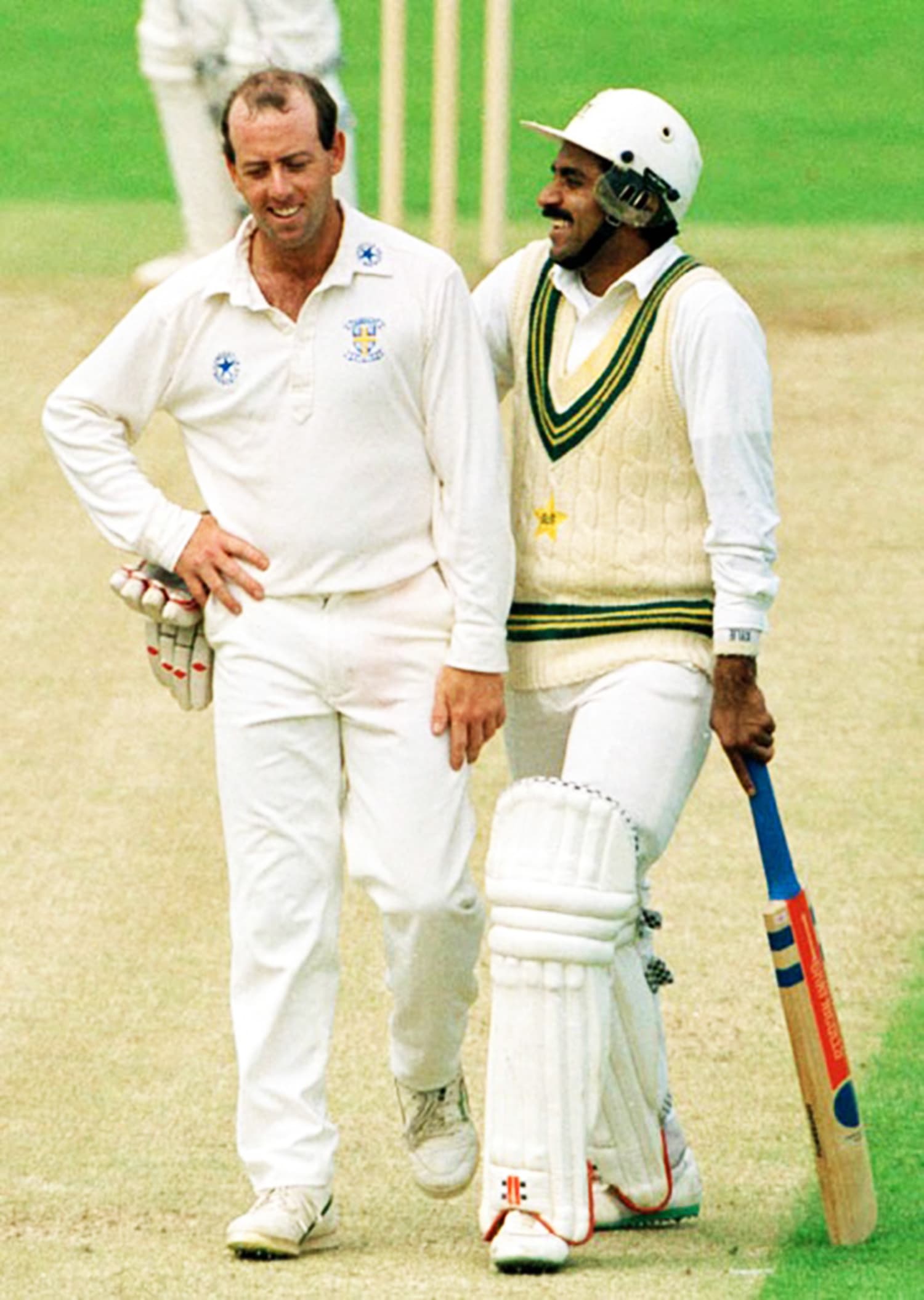

However, the cricketer who most famously reflected the curiosities that Karachi’s street cricket instills in a player was Javed Miandad (1976-96). Considered to be the best batsman Pakistan has ever produced, Miandad’s whole cricketing demeanour – sly, pragmatic, vocal, expressive, innovative, observant, distrustful and bearing a besieged mentality – brought to the world the eccentricities of Karachi’s cricket scene when foreign cricketers and media tried to understand why he was the way he was.

In his book Cutting Edge, Miandad wrote that the label of street fighter was actually given to him by the British press.

Most interesting, however, is the way Karachi’s wicket-keepers have come in and fallen out of the Pakistan team ever since Wasim Bari’s retirement in 1983. In fact, Bari is also part of these curious, fateful tales.

Bari was a regular in the Pakistan team since 1967 until he was suddenly dropped during the third Test of the 1976 series against New Zealand. He was replaced by another Karachiite, Shahid Israr. But Israr vanished as suddenly as he had appeared, and Bari reemerged.

Bari’s longest understudy was Karachi’s Taslim Arif, a much better batsman than Bari but not as clean a keeper. Bari lost his place again in 1979 and Arif finally managed to bag a place in the side. He made an immediate impact, smashing one century and two 50s. But during the 1981 series against the visiting West Indies, Arif suddenly lost all form (both as a batsman and a keeper). He was discarded and never seen again, though he did reappear after a few years as a TV commentator. Sadly, he passed away in 2008, aged just 53.

Bari returned to the side again and held on till he retired in 1983.

In 1982, when Bari became part of the ten-player rebellion against Miandad’s captaincy, Miandad brought in another Karachi wicket-keeper, Saleem Yousuf. But after his first Test, Yousuf fell ill and was replaced by Bari’s then understudy, Lahore’s Ashraf Ali.

Yousuf, briefly returned to the side after Bari’s retirement, but failed to impress.

Another Karachiite, Anil Dalpat (a Pakistani Hindu), made his way into the team in 1984. He impressed with the bat and gloves, but just a year later was discarded when, during an important ODI in Australia, he dropped a few chances off Imran Khan’s bowling. He was never heard from again.

Dalpat was briefly replaced by Ashraf Ali before Yousuf returned in 1985, but soon he was gone again, losing his place to Lahore’s Zulqarnain.

Zulqarnain made his ODI debut in 1985 and after his very first Test series in 1986 (against Sri Lanka), he was described by Imran as “the find of the series.” However, Zulqarnain fell ill after the series (jaundice) and was advised rest. Saleem Yousuf was once again called in as a stop-gap measure.

But as fate would have it, his performance with the bat (termed “gutsy” by captain Imran Khan) meant that for the next four years, he became the regular wicket-keeper for Pakistan . Zulqarnain never returned.

Yousuf’s bashful, vocal and street-smart demeanour greatly impressed two other young Karachi-based keepers, Moin Khan and Rashid Latif. They idolised him, but it was Moin who replaced Yousuf when he finally lost form in 1990 and was dropped.

From 1990 till 2004, Moin and Rashid were Pakistan’s frontline keepers. Both were as bashful and aggressive as Yousuf, but unlike Yousuf (and Moin), Latif was the most technically correct. Latif came in 1992 after Moin lost form. Then between 1993 and 2004, both kept replacing each other for various reasons.

Moin would come into form then suddenly lose it, whereas Latif always seemed to be at loggerheads with the cricket board and most of his captains. By the late 1990s, it became clear which of the two was preferred by the time’s leading fast bowlers, Wasim Akram and Waqar Younus. Akram, as captain, clearly preferred Moin; whereas Waqar, when he became skipper, ousted Moin and brought Latif back.

At one point, both the keepers were in such good form with the bat that one played purely as a batsman in the side (Moin)! Both also became captains: Latif in 1997 and then again in 2003, and Moin in 2000. Both retired in 2004, thus ending the long era of Karachi-based keepers in the Pakistan side. Until the emergence of Sarfraz.

The accidental rise of Sarfraz Ahmad

As a child and then as a teen, Sarfraz had been inspired by the likes of Moin and Latif. Like them and those before them, he was the archetypal Karachi cricketer – cheeky, vocal, innovative and yet wary.

He managed to be selected as captain in the Pakistan youth team in 2005, and in 2006 led the team to that year’s U19 World Cup win. Kamran Akmal had been the senior side’s regular keeper since 2005. In 2007, Sarfraz became his understudy.

But Sarfraz failed to make an impact whenever he was given a chance in ODIs. Finally, when Akmal lost his place in 2010, Sarfraz made his Test debut.

But also emerging during the time was Kamran’s brother, Adnan Akmal. Sarfraz wasn’t able to adjust to the rigours and pressures of the big arena and was eventually surpassed by Adnan who became the Test side’s regular keeper.

In the ODIs (and later, T20s), the team kept rotating Adnan and Sarfraz, and for a while the volatile Zulkarnain Haider and even Kamran. But by 2012, it was becoming apparent that Adnan was to be a regular in all formats of the game. Though a technically-sound keeper and a good batsman, he lacked the power-hitting abilities of his brother.

He was considered to be a notch above Sarfraz who, by 2013, had all but lost the confidence of the selectors and was almost completely discarded. Then, an accident happened.

During the first Test of the 2013-14 series against Sri Lanka, Adnan fractured a finger. Sarfraz was flown in as a stop-gap measure. He smashed a 50 in the second Test and then made a quick-fire 40-plus during Pakistan’s frantic series-equaling run chase in the third Test.

Just as illness had made Zulqarnain lose his place to a struggling Saleem Yousuf in 1986, Adnan Akmal lost it to a discarded Sarfraz due to an injury.

Sarfraz’s fighting 50 in his comeback Test against Sri Lanka in January 2014 finally cemented his place in the side.

After this, Sarfraz never looked back. He began to score big in all formats of the game but still, it wasn’t until after the 2015 World Cup that he also became a regular in Pakistan’s ODI and T20 squads. Ironically, Adnan’s batting brother, Umer Akmal, was asked to keep wickets in ODIs and T20s to make room for an additional bowler.

Nevertheless, after the 2015 World Cup, Sarfraz finally became a regular in the ODI squad and after Misbah-ul-Haq’s retirement from ODIs, was made the deputy of the ODI team’s new captain, Azhar Ali.

In 2016, Sarfraz became the ODI and T20 skipper and right away called to induct fresh talent in the side, something the team’s coach Mickey Arthur was in complete agreement with.

Sarfraz then became the vice-captain of the Test side and is now all set to become the skipper of the Test team as well.

Unlike the recently-retired Misbah who carried Pakistan to great heights during the country’s most testing years with his calm, reflective and subtle demeanour, Sarfraz is an extrovert, very vocal and animated.

Like Miandad, he loves to chat on the field and, like Shahid Afridi, he openly exhibits his emotions. But unlike Afridi, Sarfraz has a much sharper cricketing brain.

He loves to sing, recite naats and crack jokes. At age 30, he has now suddenly risen to become a well-respected character and senior in a dressing room which is now increasingly being populated by younger, hungrier players.