I was 9 the first time I travelled on an aeroplane, in 1986. We were headed to Pakistan, a country that was foreign yet held a part of us.

For my younger brothers, the flight from New Delhi to Lahore meant little glasses of fizzy drinks and an endless supply of individually wrapped chocolates.

My mother was mentally preparing herself for what she thought would be one of her last visits with her “badi ammi”, the beloved grandmother who had raised her.

My own grandmother, whom I call ammi, was thinking of too many things and nothing at all. Just the anticipation of only her third meeting in over a decade with all her siblings and her mother.

I spent the flight trying to conjure up Pakistan in my head. I imagined white, marble-domed mosques, women in flowing hijabs. All the stereotypes of a Muslim country came to mind.

That's not quite what I encountered at Lahore airport, where an aunt greeted us in slim jeans, a chiffon blouse, a Princess Diana haircut and impossibly huge sunglasses.

Pakistan: so foreign for a Muslim like me raised in chaotically heterogeneous India. Pakistan: so deeply familiar to a north Indian like me, with the same warmth verging on over-familiarity, the loud humour and obsession with good food.

Lahore: A city so much like New Delhi and so close. If I jumped in my car and drove fast, I could cover the 400 kilometres in six or seven hours. But Lahore is, in fact, very distant because of the nearly insurmountable wall of mistrust between India and Pakistan.

On both sides of this imaginary wall, live hundreds of thousands of families like mine.

When the British finally departed the Indian subcontinent in 1947, after nearly 200 years, they left it split in two.

On August 14 of that year, Pakistan was born to provide, in theory at least, a home to the region's Muslims. A day later, India awoke to freedom.

The euphoria of independence was short-lived.

Millions of Muslims, unsure and afraid of what awaited them in largely Hindu India, travelled towards Pakistan.

Millions of Hindus and Sikhs, similarly terrified and uncertain, made the journey in the opposite direction.

Hundreds of thousands never made it across.

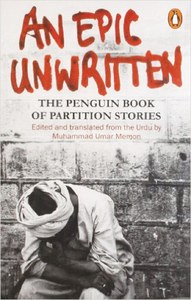

The violence that followed Partition is one of the darkest chapters of the region's history.

Cinema, literature and journalism have captured some of the horrors of that time as Muslim and Hindu mobs attacked each other. There are stories of trains full of corpses arriving in both India and Pakistan.

Of terrified refugees leaving everything they owned and fleeing with just the clothes on their backs. Of the rivers of Punjab province, the main border crossing, running red with the blood of the massacred. My family did not make those terrible journeys.

My family's story is one of a gradual migration made ever more final as hostilities between India and Pakistan made border crossings increasingly hard.

The pain of this separation is what my grandmother calls “a wound that never quite heals”. She lives in New Delhi. Her three sisters and four brothers live in cities across Pakistan.

Their adult relationships have been largely sustained by memories of their childhood in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and too-brief visits made complicated by impossible visa rules.

Very few things bring tears to my stoic grandmother's eyes. Talking about this loss of family makes her voice shake and her eyes water.

My ammi's younger sisters gradually moved to Pakistan from 1952 onward. They had been engaged before Partition, as very young girls, to young men who were from parts of the subcontinent that became Pakistan.

They eventually got married and they moved. The brothers went to visit, found good jobs and in some cases wives and chose to stay on.

Despite the bitter history of Partition and the two wars India and Pakistan fought over the Himalayan region of Kashmir in 1947 and 1965, travel was at first relatively easy, my grandmother remembers. Her youngest sister came and stayed with her for three years in the '60s.

Two of her three children were born in India. Only tight budgets and young families kept them from seeing each other more often.

That changed in 1971, when the South Asian rivals fought their third war in what was then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. Indian troops supported those fighting for Bangladesh's independence from Pakistan.

Unlike the first two wars, which ended in cease-fires, Pakistani troops surrendered to the Indian army. For several years after that, all visits ceased.

“Letters stopped coming. All news stopped,” my grandmother said. “It was a really painful time.”

It would be almost eight years before she would see her sisters and mother again. When her oldest daughter, my mother, got married in the northern Indian city of Lucknow, no Pakistani relative could get a visa to come.

The extreme diplomatic closures of the mid-'70s eventually eased, but travel never became as easy as it once was.

There are no tourist visas between the two countries. Divided families like mine can apply for visas but are not assured of getting them; it helps to know the right people.

With visas, divided families can visit each other's countries once a year for one month. They can visit three cities, reporting your entry and exit each time to local police. And they must visit them in the order listed on the visa application.

And after decades spent enduring this separation and distance from her family, a new problem has arrived for my grandmother old age.

Travel, even when it can be arranged, is now daunting for my ammi and several of her siblings, now in their 70s and early 80s.

“My passport is about to expire. Will you get it renewed for me?” she asked me recently. “I really want to go and see Mehmooda” a sister who lives in Lahore.

Then mostly to herself she said: “It's foolishness, of course. I really am not up to going through airports anymore.” I want to promise her that I will take her on one last visit.

But I don't.

For my grandmother and her siblings, a generation raised on the idea that relationships could be nurtured for long periods on the simple sustenance of letters, physical distance has brought pain, but not an emotional distance.

When my ammi last saw her youngest sister, six years ago at my youngest brother's wedding in New Delhi, there was plenty of family gossip shared.

But as a sense of shared family history fades, so do the bonds.

“The young people and the other relationships they formed ... they know nothing about us and we know nothing about them,” my ammi said to me a few weeks ago, when I asked her what made her saddest about the separation of her family.

I last visited Pakistan more than 10 years ago for a family wedding.

I met a cousin from “that side of the family” two months ago in London. We both knew the meeting would make our parents happy.

We had a cup of tea. An hour was pleasantly spent.

But I knew it, and perhaps so did he, that my two daughters and his twin boys most likely will never spend even that hour together.