Sustainable Development: How far has Pakistan come and how far do we have to go?

In this special report, Dawn's Business and Finance team reached out to SDG champions, some working in silos, to report progress and identify gaps, a year before the country has to report its progress to the UN.

The way forward

By Khaleeq Kiani

PAKISTAN secured a score of 55.6 under SDGs’ global index against a far better regional average of 63.3 and is even lower than regional peers Bangladesh’s 56.2 and India’s 58.1.

As a result, the country ranked 122 on the SDG index of 157 nations compared to Bangladesh’s 120 and India’s 116 position, according to July 2017 results.

The good news, however, is that its preparedness to deliver on 2030 targets is among some of the top in the world, raising hopes that it would not be repeating its dismal performance of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) when it missed almost all targets. Pakistan’s performance would be assessed in about 230 unique indicators on 17 goals set under UN commitments.

To begin with, parliament has adopted the SDGs as a national development agenda unlike the MDGs that were generally considered a UN-driven initiative only to be complied with by four-yearly progress reports. These reports were prepared by consultants, without any implementation mechanism in place to actually deliver.

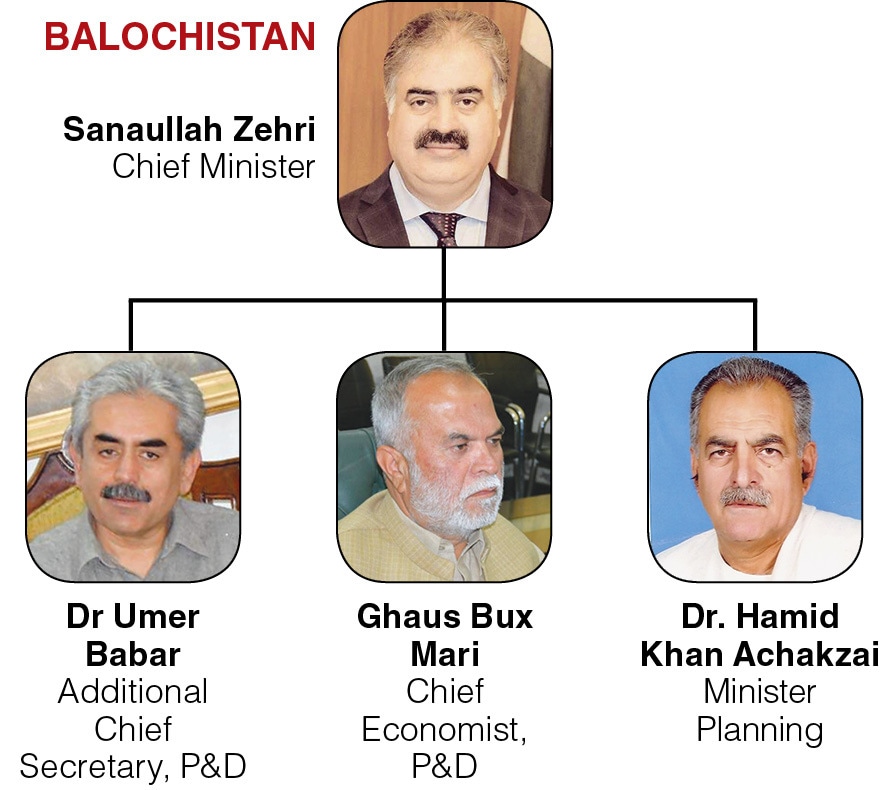

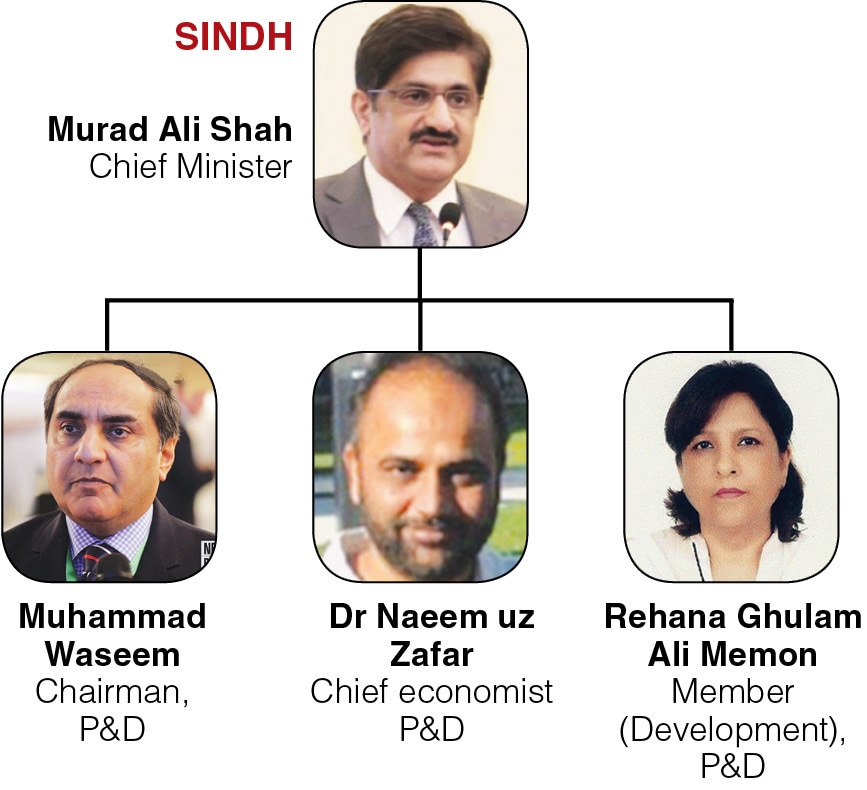

Special SDG units have already been established at the Planning Commission and provinces — as committed early last year by the country’s planning ministers — to mainstream SDG objectives by creating synergies among various federal and provincial organisations and agencies.

At the federal level, however, three separate SDG units have been created — one at Prime Minister Office, another at parliament led by Speaker Ayaz Sadiq and yet another at the Planning Commission. The three do not have an internal interface for policy coordination.

Interestingly, the first two units have huge funds at their disposal on an annual basis, with current’s year allocations estimated at Rs55 billion in the form of prime minister’s SDG programme (Rs30bn) and Rs12.5bn each for clean drinking water for all and electricity for all.

There is zero to negligible information about the outcome of the spending made through parliamentarians mostly belonging to the ruling party. There are fiduciary concerns because this amount is normally spent outside the normal financial regulation mechanism.

A step forward, the mission for SDG implementation has been taken to the grass roots level via the local government (LG) system — for bottom up engagement and implementation of targets as majority coverage areas stand devolved to the provinces — and onwards to the district level.

Representatives of the LGs at the district level were engaged through a national conference where they were given a chance to express their priorities. Most referred to education, health, water and unemployment as top issues. Interestingly, sanitation and climate missed their radars, perhaps because of lack of general awareness. It also emerged that absence of bathrooms was impacting female education.

A major challenge for the planning commission appeared to be the data gap reporting analysis. It was noted that of the 230 indicators, reporting of data on 14 overlapped to where either data was not being reported at all or was being reported on the sidelines. Reporting on around 45 per cent variables was available but was not being computed.

The remaining 55pc variables are of a serious nature. The newly inducted Deputy Chairman Planning Commission, Sartaj Aziz, with his development background has required the commission to replicate these goals as national development goals and be made part of the next five year plan 2018-23 — prioritising education, health, economic wellbeing, water, peace and security and affordable energy, in that order. He has directed that these goals be made part of the planning processes and given to the line ministries for implementation.

Another problem at the gross root level that was noted was the absence of administrative and financial powers of the district governments. An even greater challenge was how to create awareness and knowledge about how critical the SDG goals were to uplifting the lives of the people and how to make the process sustainable. At the planning commission level, the authorities proposing any big project are required to articulate if and how much their project papers were related to the SDGs.

But more importantly, authorities have to work on balancing outcomes of various goals. Pakistan’s performance on prevalence of poverty is impressive with only 4.1pc population reported poor at $1.90 per day and estimated to go further down to 0.2pc by 2030.

But this performance does not appear to be translating into other goals. For example, if the rate of poverty is so low why then are 45pc children under 5 years of age growing stunted and why is 22pc of the population still undernourished?

It transpired that average family budgets had diverted towards dense food — meat, milk etc. The planning commission analysis showed the country’s philanthropic network was actually supporting the social network to a great extent.

Also, while Pakistan’s overall economic indicators were comparable with emerging economies its general social indicators were lagging behind even Nepal and Bhutan.

It has been noted that Pakistan is very poor in terms of water quality despite a number of initiatives at the federal and provincial level. The indicators have gone down drastically over the last 10-15 years resulting negatively on health and nutrition and resultantly education.

Poor water quality arose out of untreated industrial waste and arsenic flowing into drinking water resources, causing increased prevalence of hepatitis, cancer and other diseases.

In fact, all this appeared to boil down to governance problem as housing societies and industries expanded without planning in all major cities, leaving untreated industrial water and sewerage waste into canals and water channels, affecting urban infrastructure.

As part of the SDG monitoring unit, a score card is being developed on how much expenditure out of the federal or provincial development plan has gone into a district and what the outcome has been.

A sample study showed a Rs15,000 per capita expenditure out of the provincial annual development plan last year compared to Rs40 in Layyah District. A next step would be to explain the outcomes of these expenditures on health, education and other rankings.

Click on the tabs below to learn more about the progress Pakistan made to achieve SGDs.

Another chance to score!

By Afshan Subohi

FOR a just, prosperous and secure Pakistan, defending democracy and defeating rogue outfits with obscurantist mindset are vital.

Reorienting the decadent state structure that protects and promotes parasitic segments at the cost of dynamic sections and ideas is also essential. All this naturally is a tall order and is impossible to achieve without public pressure and active citizenry.

There is an undeniable need for improving data, planning, financing, coordination, institution-building, delivery arrangements and development deals, but the experience of the first 15 years of the current millennium at our end has only endorsed the perception that tangible progress in the desired direction will need democratisation and decentralisation at both planning and implementation tiers.

This time around the federal government got the plan endorsed by parliament and made an effort to embed the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in its growth strategy.

It engaged not just the provinces but also the districts, as the responsibility of the social sector has been devolved in the wake of the 18th Amendment.

The engagement of the United Nations with the corporate sector also mobilised various subsidiaries active in Pakistan to incorporate some goals in their programmes. The UN and its multiple organisations are doing their bit as well.

But SDG implementation continues to be an exercise that people know nothing about. On their own initiative, some media houses cover the subject every now and then but this is certainly not enough as the word is not yet out; not with any degree of intensity.

Political parties and leaders might agree with the goals, but do not find them worthy of propagation. On condition of anonymity, a senior official said the governments led by different parties in each of the four provinces are too focussed on the general elections due next year to really care about any global agenda like the SDGs.

“Honestly speaking, SDGs are treated as something of mere academic value, and alien in the world I move in. I am not saying that development is out of sight. No, in KP a lot been has done in the health and education sector but all that is independent of the SDGs,” a top bureaucrat said over the phone.

Pakistan was among the first few countries in the 2000s to translate the MDGs into national goals and draw on paper a detailed framework complete with quantifiable indicators and annual benchmarks for each of the eight goals. In the concluding report in the termination year 2015, Pakistan accepted that goals were missed, some like health and climate, by a wide margin.

Sadly, the country continues to fare low on most global indices gauging efficiency, equity and sustainability. Some progress has been made, but performance is assessed to be far below actual potential.

The asset base continues to be skewed, limiting the accessibility of economic opportunities to the underprivileged. In Pakistan, one per cent farms cover one quarter of the agriculture land and 62pc comprise five acres or less. About half the rural households are landless.

According to the current Social Policy and Development Centre (SPDC) report, the composition of growth tends to widen inequality: every one rupee expansion in national income places 36 paisas in the pockets of the rich and 03 paisas in the pockets of the poor.

The tax regime is regressive; 80pc of tax revenue is derived from indirect taxes. The richest 10pc pay 10pc of their income in indirect taxes against 16pc paid by the poorest 10pc.

The introduction of the Benazir Income Support Programme deserves a mention as an initiative to introduce and extend social protection network for the poorest of the poor. According to data currently over one third of Pakistan’s population (39pc) lives in multidimensional poverty.

Pakistan’s slide on the Global Food Security Index from 75th five years back in 2012 to 79th currently is another disturbing factor. A World Health Organisation study suggests that 40pc of our children are underweight. The Food and Agriculture Organisation has projected that 37.5 million people are undernourished. Almost 60pc Pakistanis are food-insecure because of the neglect of rural economy.

The statistics in the health sector are even more distressing. People are turning to soothsayers as family budgets fail to cover the rising cost of healthcare. It is not surprising that 44pc of all children in the country are stunted and 9.6m experience chronic nutrition deprivation. Pakistan’s ranking in the Maternal Mortality Ratio Index has slipped to 149, recording a pretty high ratio of 276 deaths per 100,000 births.

The situation is comparatively better in education but nowhere near the performance of our counterparts in the region. Millions of children are deprived of education. The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2015 survey found that 20pc of children aged 6-16 years were not in school and the rest were not learning much for lack of quality. Despite several initiatives to strengthen the legal framework for gender parity on Gender Gap Index, Pakistan is ranked among the last few.

Access to clean drinking water is limited, and hygiene and sanitation facilities are considered the privilege of those residing in better city areas. Pakistan is identified amongst the most vulnerable countries to climate change. It threatens food, water and energy security. The devastating avalanches, earthquake and floods have failed to shake the government to pay the required attention and divert resources to respond to threats and risks.

In the last budget, allocation of less than one per cent of PSDP reflects the weight the government assigns to the issue. Pakistan signed the Paris Agreement on Climate Change where signatories pledged to reduce carbon emission by 15pc of the current level. However, the government has since encouraged coal-fired power projects that, by its own admission, would worsen environmental pollution.

The plight of work force in a labour-abundant country that experienced deindustrialisation is too obvious to escape the attention of anyone interested. Limited decent work opportunities and several hundred chasing each job opening has compromised the bargaining position of workers and has made them vulnerable to exploitation. The demise of trade unions has also left them with no option but to turn to their clans and bradaris for support.

Implementing the SDGs is said to be a huge challenge, particularly for Pakistan, which is facing a certain degree of diplomatic isolation and is clearly indecisive about the path it wishes to take for going forward

According to relevant research studies, Pakistan needs to create two million jobs annually to absorb out-of-job youth over the next three decades. The country desperately requires reviving and expanding the manufacturing base to address the employment challenge. If CPEC investment in infrastructure helps diverts private capital back to manufacturing from short-term quick-return investment avenues, it could change Pakistan’s story.

The country has yet to learn the benefits of sustainable practices and lifestyle and the value of scientific and technological capacity-building. The level of wastage is depressingly high in Pakistan. Be it agriculture produce, water, energy and much else, we have proved to be reckless.

Recently it was disclosed at a government forum that we use 1,070 litres of water for each dollar worth of GDP compared to the Asian average of 128 litres. The energy efficiency is 128 megajoules (MJ) per dollar against the Asian average of 16 MJ.

The SDGs represent a universal set of 17 goals, 169 targets and 200-plus indicators that UN member states are expected to localise and implement during 2015-30.

According to sources in the know of developments in Pakistan, the work to embed the SDGs in the long-term development framework, Pakistan Vision 2025, started in 2013; two years before they were formally launched by the UN.

The first national monitoring report from member countries will be due by the end of 2018. In Pakistan, the Planning Commission is supervising and coordinating work on SDGs between line ministries and different tiers of governance.

It is said to be a huge challenge, particularly for Pakistan which is facing a certain degree of diplomatic isolation and is clearly indecisive about the path it wishes to take going forward. The tension in varied pillars of power in a society divided along all conceivable divides makes progress still harder.

‘We, the local leaders, are convinced that by giving specific attention to the localisation of all goals, the new agenda will trigger an important transformation in our joint act’ — Local government SDG summit declaration.

Local governments are key to effective implementation

By Nasir Jamal

ON March 9, the Planning Commission of Pakistan organised a Local Government Summit on Sustainable Development Goals.

At the end of the day, the 75 heads of local governments, gathered from across the country, adopted a Declaration calling for administrative and financial empowerment of the district governments for implementing the global goals.

“We, the local leaders, are convinced that by giving specific attention to the localisation of all goals, the new agenda will trigger an important transformation in our joint act,” the declaration underscored.

Indeed, local governments are the key to successful and effective implementation of Agenda 2030 in Pakistan. Yet this tier of government remains the weakest link in the entire chain as the provinces continue to control most administrative, political and financial powers.

“Localisation of SDGs and empowerment of local governments is going to be very critical in implementation of the global goals and better outcomes,” Zafar ul Hasan, Chief Poverty Alleviation and SDGs at the Planning Commission of Pakistan, emphasised during a telephonic conversation with Dawn. “You cannot expect to achieve the SDG targets without active involvement of districts and empowering them.”

Adopted at the Sustainable Development Summit in 2015, Pakistan was one of early nations to declare the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development as national agenda through a resolution in the National Assembly in the beginning of 2016.

“Early conversion of SDGs into provincial socio-economic development strategies, policies and budgets will be a major challenge in the way of achievement of the global goals by 2030,” a Punjab planning and development department official said on condition of anonymity.

“Pakistan missed the MDGs because their implementation was considered a federal responsibility. But the devolution of the federal departments and functions after the 18th Amendment to the Constitution offers a very big opportunity for localisation and achievement of the SDGs.”

Learning from the past, the government has engaged with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) this time around to build an institutional framework, both on the federal and provincial level, by establishing SDG Support Units in order to provide mainstreaming, acceleration and policy support for SDGs.

While these units have already become functional in Punjab and Sindh, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are in the process of creating these units.

The federal SDG Support Unit created at the Planning Commission will not only oversee implementation of the global goals in Azad Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan and federally administered areas but also coordinate with the provinces. They will help them generate data at regular intervals for future planning and resource allocations, provide evidence, analysis and perspective to inform public policy in the context of SDG targets.

“The SDG Support Units are chiefly responsible for supporting the federal and provincial governments in planning and implementing the SDG Framework through a locally driven approach that focuses on planning processes, data availability at district level and utilisation of local budget and locally generated resources.

“The four key focus areas of the SDG Project are: aligning plans and policies to Agenda 2030; strengthening monitoring, reporting and evaluation capacities; aligning financing flows to the Agenda; and fostering innovation to accelerate progress,” according to an UNDP office in Islamabad.

These support units, according to Mr Hasan, will help provide policy consistency and institutional framework for vertical coordination necessary for SDGs implementation.

The provincial P&D department official agreed that local governments have to play a critical role in achieving the global sustainable development goals because “they are closer to the people, are aware of the local needs and issues, and easier to hold accountable for failing to meet their targets.

“The smarter strategy for the provinces will be to involve local representatives in the assessment of public need for formulating budget priorities and effective development policies.” he concluded.

By Amin Ahmed

THE government’s commitment to achieving the SDGs has yet to be translated into an action plan. The first two goals — ending poverty and achieving zero hunger — still await approval of a national food security policy.

The business-as-usual approach is not going to make any significant impact on poverty reduction.

A more innovative and comprehensive approach is needed, with increased focus on reducing the economic, social and environmental risks confronting the poor, according to the United Nations.

Mina Dowlatchahi, Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) representative in Pakistan, says the National Zero Hunger Special Programme — being formulated by the Ministry of National Food Security and Research in collaboration with the FAO and World Food Programme — foresees social protection, school feeding and nutrition education actions, combined with longer term interventions on ‘farmer field schools’, sustainable agriculture intensification and diversification approaches, and the development of linkages to markets for smallholders.

Measures to achieve zero hunger are an integral part of the final draft of the national food security policy.

“We cannot end hunger and all forms of malnutrition by 2030 unless we address all the factors that undermine food security and nutrition, including socio-economic stability,” Ms Dowlatchahi says.

“Securing peaceful and inclusive societies (SDG 16) is a necessary condition to that end,” she says.

In Asia-Pacific, Pakistan is among the few countries which have contained the hunger to some extent. The percentage of hunger during the 2014-16 period declined from 25.1 per cent to 22pc. Within the region, the proportion of people affected by hunger in 2014-16 increased from the level that existed in 1990-1992.

According to the latest edition of the annual United Nations report on the food security and nutrition, the challenge is that there is more than enough food produced in the world to feed everyone, yet 815 million people (or 11pc of the global population) faced hunger last year.

The highest number of undernourished people was in Asia because of its large population.

According to FAO, around 520m people in Asia, 243m in Africa, and 42m in Latin America and the Caribbean did not have access to sufficient food energy.

Poverty eradication will be challenging with the occurrence of climate-related events because the region is particularly exposed to the impacts of climate change, with nine Asia-Pacific countries on the list of the 15 countries that are the most exposed and vulnerable to natural hazards.

The first SDG goal is to eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, currently measured as people living on less than $1.25 a day. It

aims to reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions by 2030.

“While the region is making progress towards achieving the SDGs on poverty, education, economic growth, industry and infrastructure, and life below water, we are seeing slow progress towards ending hunger, achieving food security, delivering agricultural sustainability, ensuring good health and well-being for all, and achieving gender equality,” said Dr Shamshad Akhtar, executive secretary of UN’s Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (Escap).

Pakistan is the first country to endorse and adopt SDGs in parliament as part of its national agenda and now these goals are known as national development goals (NDGs). A parliamentary task force and an SDG secretariat have also been set up.

“The SDGs are not just a part of a top-down international agenda, but are also essential for Pakistan’s prosperity, development and the well-being of its people,” according to Interior and Planning Minister Ahsan Iqbal.

On the other hand, in the Asia-Pacific SDGs Outlook report, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) examined each of the 17 broad goals and describes the outlook for achieving each one in the region. It singles out “bright spots” and “hot spots”, provides insights about each goal and points to emerging issues and reveals many of the common challenges that governments will confront as they work to develop appropriate responses to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The ADB says that achieving zero hunger will be challenging due to the convergence of expanding populations, climate change, fertiliser overuse, competing use of land for food, energy and industries, changing consumption patterns, the ageing population of working farmers and the degradation of agricultural land.

The bank believes that regional countries need to pay more attention to growth in their agricultural sector and to supporting diverse food systems. Evidence consistently shows that growth originating in agriculture has a stronger impact on poverty and hunger reduction than growth originating in other sectors.

The deadline of SDGs ensures sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production; help maintain ecosystems; strengthen capacity for adapting to climate change; extreme weather; drought; flooding and other disasters, and that progressively improve land and soil quality.

The region is the world’s largest producer of cereals, vegetables, fruits, meat and fish, with strong growth in all areas. Agricultural production has been increasing steadily since 1990. Measured in terms of constant prices, the value of food produced in the region increased from $736 billion in 1990 to $1.351bn in 2013.

Agricultural productivity in the region, as measured by the value added per worker, has generally been rising. However, it has been a slow rise in South Asia where, with the exception of a few countries, it remains a fraction of what has been achieved in industrialised countries.

The target sets to increase investment, including through enhanced international cooperation, in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development and plant and livestock gene banks in order to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular least developed countries.

Climate change threatens all dimensions of food security. Projections show that increasing temperatures will result in decreased yields, especially in South and Southeast Asia, and increased incidence of pest and disease outbreaks.

The widespread melting of glaciers and snow cover in the major mountain ranges of Asia will affect the volume and timing of water flows and ultimately reduce the availability of irrigation water downstream. The effects of climate change on agricultural production and livelihoods are expected to intensify over time.

Agricultural productivity of high-income countries in the region is 67 times higher than that of least-developed countries.

The rate of growth of government spending on agriculture in the region has slowed down since the food price crisis, according to Escap.

The availability of water is also a challenging issue, with agriculture being a major user. The proportion of water withdrawn for agriculture is more than 90pc for 13 countries in the region, particularly in Central Asia.

Nearly all countries in the region are experiencing increasing pressure on water resources due to their growing populations and economic development.