Dawn Delhi IV: The making of Pakistan

IT was on August 21, 1945, when the Viceroy announced that elections would be held in the cold weather at the end of the year. Aligarh Muslim University played a major role in League plans for the elections as did colleges in the Punjab. The League set up a training camp on campus at Aligarh at the end of 1945 with some 650 students attending the camp. Of the 11 topics covered in the course offered at the camp, one was on ‘Islamic history’ and another was on the ‘The religious background of the Muslim League and Pakistan’.

The following month an election office was set up at Islamia College, Lahore, and 200 students were deputed to tour 20 constituencies covering 400 villages. In the course of the campaign it claimed that 60,000 villages were visited by these student campaigners. Aligarh students clad in black sherwanis and Turkish caps created a very favourable impression when, like other students and League representatives, they spoke in mosques. The students were carefully coached to express their messages in religious terms and to equate the Muslim League with Islam. Dawn recorded their names and activities.

In the Punjab, the religious leadership based on the numerous shrines in the rural areas also played a large part in the League’s campaign. These shrines were the tombs of sufi saints who propagated Islam in the Punjab, especially western Punjab when it was an outpost of Islam. The religious leader of these shrines, the sajjada nashin, was normally a descendent of the original saint; he was a teacher, a pir and he had disciples, murid, who would make payments in one form or another. Over time these sajjada nashins became intimately involved in rural society, exerting not only religious leadership but political and social influence as well, much like the mullahs in the mosques, both urban and rural.

VOLUNTEERS IN THE ELECTION

When the pir became vociferously involved in local politics he wielded a great deal of influence. By the time of the 1945-46 general elections five of the important sajjada nashins had come over to the League. Many of them were revivalists and interpreted the Pakistan Movement as the establishment of a religious state. In addition, as one Unionist worker complained in December 1945, a pir was issuing fatwas that the Muslim League was the only Islamic community and all the rest were kafirs.

Dawn followed the events in the Punjab, as it did in every other of the crucial provinces for the Pakistan Movement, and reported widely on tours of League workers and meetings held throughout the provinces. On October 13, 1945, it ran a front-page story titled ‘Muslim Interests Mean Nothing to Unionists’ and that the Unionists were ‘Pawns in Non-Muslim Hands’. The article that followed was an insinuation that the Muslim members of the Unionists were not good Muslims. These were the kinds of lines that League workers would use during the election campaign. Dawn on October 24, 1945, reported that the Punjab Muslim Students’ Federation had established an Election Board to propagate the League’s message all over the state. It reported that “over 200 Muslim students of the various local colleges have been enlisted to work as volunteers in the election campaign”. They undertook a short training course and then were sent in batches to various parts of the province.

League planning for the election began at Liaquat’s house in Delhi when Dawn announced in its October 1, 1945, issue that a meeting of the Central Parliamentary Board would be held later that day and the Committee of Action would meet over two days on October 9 and 10. What was important for the League was the choice of candidates for League tickets, the organisation of meetings, the provision of student workers to campaign in critical constituencies, and, very importantly, the creation of literature that would be distributed during the campaign.

In ‘League News from Provinces’ on October 2, 1945, Dawn reported that the Muslim Writers’ Association met at Aligarh on September 27 and that “separate Committees were formed to carry on the League propaganda work in different languages and to translate the original works for free distribution among the Muslim masses”. It had created an English Publication Committee, an Urdu Publication Committee and a Committee for Translations. A Study Circle trained workers and sent them to different parts of the country and the Committee also cooperated with provincial parties to use the literature it had created. These and dozens of other activities were all preliminary to the campaign itself which was launched the same month.

A QUESTION OF LIFE AND DEATH

The success of all these League activities can be gauged by the number of people who now wanted to run on the League ticket. Dawn reported on October 8, 1945, that in the United Provinces, for example, some 20 people applied for the League ticket for the six Muslim seats for the Central Legislative Assembly. Another was the report in Dawn on October 12, 1945, that in the Punjab ‘17 Congress Stalwarts Join Muslim League’ and the Central Parliamentary Board had met for three days to come up with the list of 21 candidates for the 30 Muslim seats for the Central Legislative Assembly; the rest of the names would be announced later.

On Thursday, November 1, 1945, Jinnah officially kicked off the League campaign with Dawn reporting the event the following day with the headlines of ‘It Is My Duty To Serve Muslims’, ‘Mr. Jinnah Inaugurates Campaign’, ‘Even If You Don’t Vote For Me I Shall Work For You’ and ‘Grave Issue Confronts Indian Mussalmans’. The article reported Jinnah’s speech in Bombay to a large audience of Muslims inaugurating the first League election campaign meeting where he claimed that the Muslims were “today politically more conscious than the Hindus”. The election, he went on, would decide the future of India. It was not a question of voting for this or that candidate but it was the question of a hundred million Muslims. “The elections will give a clear verdict on the issue of whether the Muslims of India stand for Pakistan or for Akhand Hindustan. It is therefore a question of life and death with Muslims of India.”

The editorial that day had the title of ‘Never Again’ and regurgitated the story of the “terrible suffering to which Muslim minorities in Hindu-majority provinces were subjected during 1937-39”. Alongside it was another story on the misdeeds of the Congress when the ‘Tragic Story Of 1937-39 Re-Told’. It was the first of many articles spread over several days in the ‘It Shall Never Happen Again’ series. By December 20, 1945, Dawn had published version 31 in the series. In addition to the column ‘League News from Provinces’ there were hundreds of stories, large and small, mostly small, about League activities. League workers would faithfully repeat these campaign messages in the days to come in many parts of northern India.

The history of the League campaign in the 1946 elections and the remarkable victory it achieved has yet to be written but it was celebrated as the glorious victory it was in the pages of Dawn which announced the wins as they came in and culminated the month-long saga with stories galore about the mammoth meeting of some 450 League legislators organised in New Delhi to celebrate the League success in the elections.

A GREAT TRIUMPH

The meeting was ‘The Muslim League Legislators’ Convention’ held between April 7 and 9 on the Quadrangle of the Anglo-Arabic College. League legislators of the central and provincial legislatures from all over India journeyed in triumph to Delhi to take part in its proceedings held in a boisterous mood with the final session not ending until 2am. It was a Who’s Who of Muslim League India with Sir Feroze Khan and the Nawab of Mamdot of the Punjab, H.S. Suhrawardy of Bengal, Chaudhury Khaliquzzaman of the United Provinces, Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah, Premier of Sindh, Sir Mohamad Saadullah of Assam and Abdul Qayum Khan of the North-West Frontier Province were some of the notables in Delhi to celebrate this great triumph.

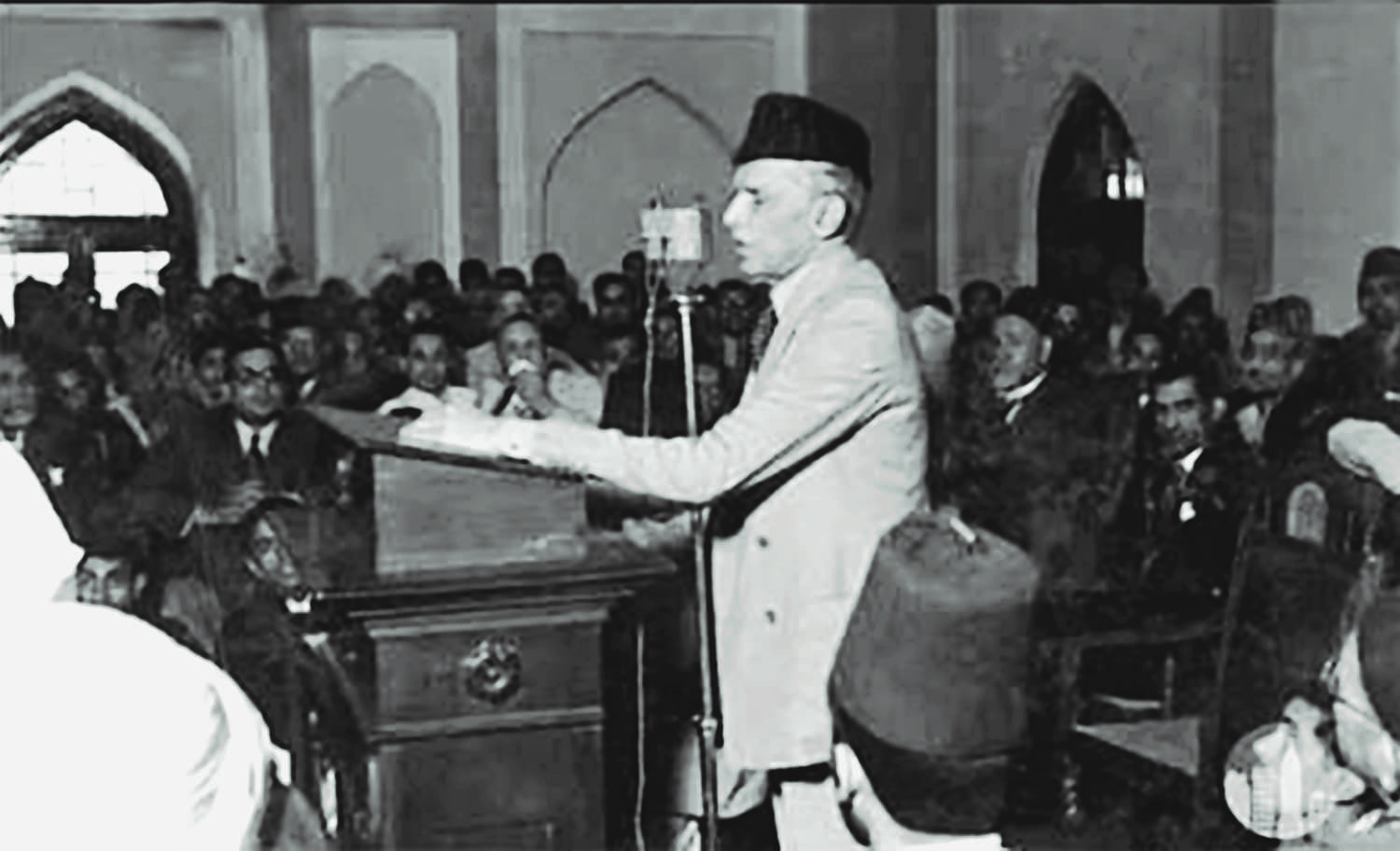

The highlight of the meeting was Jinnah’s speech on April 8 which was reported at great length in Dawn the next day and in numerous articles in the days and weeks that followed. Inter alia Jinnah said that for Muslim India the conception of a United India was impossible and if the Government attempted to impose a unitary constitution-making body, then Muslim India would “resist it by all means and at all costs”.

To cheers he told the mass audience that he informed the Cabinet Mission that there could be no compromise on the fundamentals of Pakistan and its full sovereignty. With regard to the election results, he said to appreciative ears that by winning about 90 per cent of the Muslim seats “we have achieved a victory for which there is no parallel in the world”.

Jinnah then turned to the recent comments of Patel and Nehru that they would not accept two states in South Asia and especially Nehru’s comment that independence should come first and then a constitution-making body would be formed to write the constitution. For Jinnah and the League this meant putting the minority at the mercy of the majority with the certainty that the Congress should dismiss totally the demand for Pakistan. Jinnah called this a “Fascist Grand Council”. He concluded his lengthy speech with the words: “God is with us because our cause is just and our demand is just both to Hindus and Muslims inhabiting this vast sub-continent. And so we have nothing to fear and let us march forward with complete unity as disciplined soldiers of Pakistan.”

With the great election victory, the League could claim that the Muslims of India had voted for Pakistan and this was a claim that the League would make until Pakistan was actually created on August 14, 1947. Later on in the year, in August, the League would unleash its own civil disobedience movement to convince the British that they should not ignore the League and hand over India to the Congress and allow the party to write a new constitution as Nehru and others had been demanding.

TWISTS AND TURNS

Dawn would continue to play a major role in all the twists and turns of the negotiations and political manoeuvres of the end-game of the British raj. This involved the Cabinet Mission, League participation in the Interim Government, the second Simla Conference, the negotiations with the British Government in London and the negotiations with Mountbatten that finally led to the establishment of Pakistan. Dawn played a major role in helping to shape public opinion, especially Muslim public opinion, and to ‘spin’ the League message as it twisted and turned to counter Congress and British efforts to prevent the creation of Pakistan. This included explaining at length the League’s rejection of participation in the Interim Government and then its acceptance; its acceptance of the Cabinet Mission Plan and then its rejection.

Throughout, Muslims of India looked to Dawn for the attitude of the League toward the latest turn in events, and the British carefully scrutinised its pages for an insight into League thinking and to plan its own moves. A variety of factors led to the creation of Pakistan in 1947. The first was the creation of a democratic system that would establish the legitimacy of national spokesmen and the legitimacy of the causes they espoused. It was this democratic system that gave credence to the claims of national spokesmen made important by their electoral success (although Gandhi was the exception to the rule).

The second great factor in the creation of Pakistan was the outbreak of the Second World War and the political blunders perpetuated by the Congress such as resigning from their government positions in 1939 in protest over India’s declaration of war without proper consultation with the Congress, and their Quit India Movement in 1942 which led to Congress leaders’ imprisonment for the major part of the War, leading to a vacuum of power which the League happily filled and of which it took enormous advantage.

The third factor was a recognised single League leader around which the League rallied. That was Jinnah, the Quaid-i-Azam, the ‘Great Leader’, a remarkable man in many senses whose political strategy, unlike the Congress’, was superb. His ascendency to the apex of Muslim leadership in India was facilitated by the premature death in the Punjab of Fazl-i-Husain and Sikandar Hayat. It was to the great good fortune of proponents of Pakistan that his own health held out until Pakistan had been created.

AN IMPORTANT FACTOR

Political fatigue by the British and the aspiration to leave India sooner rather than later amid the usual propensity of an imperial power to turn its back on colonies when the time comes to depart, no matter what the deadly consequences for the citizens they leave behind, as they demonstrated so fatally in India and would do so a few months later in Palestine, played a large role.

Finally, the last Viceroy’s love of speed in everything he did, including the demission of power in India, meant that independence would be pushed through within weeks; if the creation of Pakistan meant facilitating speed, then Pakistan it would be no matter what the consequence of a hasty retreat of the forces of law and order in the land might mean.

The elimination of any of these factors would have changed the political situation in the years leading to Partition. Above all, however, the creation of Pakistan is a testament to a remarkable decade-long political story. It is a testament to the sure-handed political leadership of Jinnah and his creation as a charismatic leader. It is a testament to the work and devotion of a large cadre of League supporters and workers in many parts of India, especially in the United Provinces, Bengal and the Punjab.

The creation of Jinnah as the ‘sole spokesman’, the organisation of the League, the mobilisation of Muslims behind the League, and the message that in the pre-television age the League needed to transmit to the people of India and the British, were all facilitated and in many ways made possible at all, was through its own creation, that is, through the pages of Dawn: Dawn, too, therefore, was a factor, an important factor, in the creation of Pakistan.

This concludes a four-part series of articles on Dawn Delhi. Also read the first, second and the third part.

Excerpted from ‘Dawn & the Creation of Pakistan’, Media History 2009, SOAS, London.

The writer is Professor of History, Eastern Michigan University, USA

This story is part of a series of 16 special reports under the banner of ‘70 years of Pakistan and Dawn’. Read the report here.