Concrete skeletons litter northern Pakistan — monuments to the government’s failure to rebuild thousands of schools destroyed by the massive 2005 earthquake. About 67 percent of the schools in the region were destroyed or damaged by the calamity.

Only around half of the schools have been rebuilt, which numbered “no less than 6,000” according to early estimates. Thousands are in various stages of construction, abandoned by contractors for years at a time, or with their construction “yet to be started” according to the latest official figures.

Two schools in the tiny mountain village of Pehlwan, above Abbottabad, have been under construction for 10 years. A school in the neighbouring village is missing a roof.

How ERRA became a white elephant while children waited for schools to be rebuilt

“Everywhere there’s ERRA, there’s a Pehlwan,” says an education official in Abbottabad, referring to Pakistan’s Earthquake Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Authority (ERRA), the federal government agency in charge of reconstruction.

***

When it was created in the aftermath of the October 2005 earthquake, donor-funded ERRA touted the slogan “Build Back Better”. Donors pledged 6.3 billion dollars — a billion more than needed. ERRA resolved to take on extra duties like student enrolment, teacher training and establishing parent-teacher committees. But the organisation struggled to simply build back what was destroyed.

“The government didn’t know what to do. They were completely lost,” recounts Taimur Sarwar, a former technical expert with UN Habitat.

Today, Lieutenant-General Nadeem Ahmed who set up ERRA and his UN counterpart Andrew MacLeod admit that it took time to figure out a viable plan. The scale of the crisis was simply unprecedented.

“People overestimate the ability of any government to respond. There are unreal expectations about the speed at which they can reconstruct,” says MacLeod.

The challenges started with setting up a new government authority in the midst of a crisis. ERRA’s second annual report describes a “hurriedly put together organisation … suffering from an acute identity crisis” for the first year and a half of its existence.

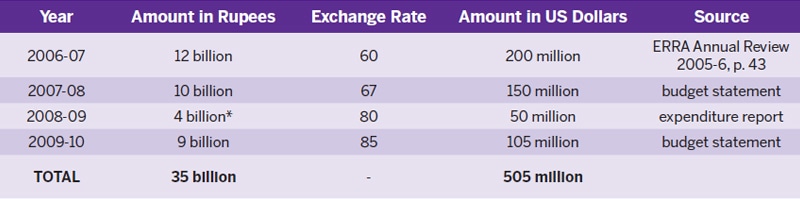

- This figure is lower because it is expenditure, not the amount budgeted. The budget is not available for this year.

“Matters were not made easy by the hordes of disaster experts and agencies daily descending on the few officers and consultants manning various planning positions, each carrying a recipe for sure success,” the report chronicles. Salary differences between Pakistani government staff and donor-funded positions were also “a source of friction and affected the morale of regular staff.”

In October 2006, a year after the earthquake, ERRA announced it would rebuild 25 percent of the destroyed and damaged schools — or 1,574 schools — that year. By the end of the year, though, ERRA had completed only 70 schools.

Similarly, by the end of three years, the ERRA had completed construction of only 215 schools — four percent of their total target.

MacLeod says then-President Pervez Musharraf insisted on the three-year target. A more realistic estimate would have been eight to 10 years, he says, but “it should be 95 percent done by now.”

***

Contractors did not bid on ERRA’s first contracts. The organisation used standard government construction rates of 11.50 US dollars per square foot, estimating that a three-room school would cost 40,000 dollars on average. They forgot to include transportation to off-road, scattered mountain communities, which doubled or tripled costs. Moreover, making buildings seismically safe added 30 percent to the cost, according to Ahmed. The estimates allowed for only a five percent margin.

Officials recall that the actual cost ended up being 20 dollars to 30 dollars per square foot. Sometimes materials could only be transported with porters or donkeys or contractors had to build roads first to get to far-flung sites.

International organisations paid higher rates, so contractors were not interested in Pakistani contracts. “I remember USAID paying 40 dollars to 45 dollars [per sq foot],” says Ahmed.

Many places did not have water, which is necessary for construction. One contractor said he paid over 1,400 dollars per day to bring water to the village from the nearest town — an unplanned expense he could not claim.

ERRA re-bid the contracts at higher rates, but those who won them subcontracted them to a litany of smaller companies. Hence, oversight became a challenge.

Then, the value of seismically safe land shot up. “In most areas, a grandfather in his 50s or 60s donated his private property for the construction of a government school,” remembers a senior ERRA official who asked for anonymity. But land titles had not been transferred to the government. “The grandchildren wanted the government to buy that land from them now. But ERRA cannot buy land.”

Once construction got started, there was a shortage of materials and contractors struggled to comply with new building codes.

“We spent a year discussing bricks,” remembers Nilofer Qazi who was a field officer for UN Habitat. “Bricks could no longer be 5.5 inches. They had to be eight inches because that was the global standard. But our moulds would not allow it. We had to go to factories and brick kilns and monitor the quality of the cement, water and materials that go into making a brick … We lost people [in the earthquake] because of bad construction. To not pay attention to the quality of construction would be criminal.”

Reconstruction did not gain steam until 2010, when ERRA had built over 1,000 schools. By then, attention and budgets shifted to newer catastrophes unfolding in Pakistan: an internally displaced persons (IDP) crisis in the aftermath of military operations in Swat and the floods in 2010.

“From 2009 onwards, we started facing difficulty in getting funds from the government of Pakistan. We told the contractors to stop their work,” says the ERRA official. Contractors “demobilised”, removing machinery and manpower from construction sites.

***

By 2011, 88 percent of school projects that were sponsored by donors or local civil society organisations were complete compared to only seven percent of schools paid for by the Pakistani government.

Pakistan’s Rural Support Programme Network (RSPN) had worked with community organisations in the affected areas for years before the earthquake hit. The RSPN put the communities in charge of rebuilding, paying them upon completion of work.

“It’s a self-help approach. With some of these groups, we had done such work before, so it was not new,” reflects Shandana Khan, CEO of RSPN.

Another government evaluation found that the reconstructed schools run by local civil society performed better than those run by the government and foreign donor-funded schools, in terms of lower teacher absenteeism and fully functioning school facilities such as toilets, libraries and science labs.

“The lesson is that if you work through communities — and people were so keen to rebuild — then it works,” says Khan.

***

The estimated cost of school reconstruction was 472 million dollars. Pakistan budgeted at least 500 million dollars on education, but spent less than 70 million dollars for that purpose up until 2010. These figures do not include what donors spent directly, outside government channels.

The Telegraph reported that in 2009 President Asif Ali Zardari began diverting over 300 million pounds to other government projects. “With the PPP [in power], reconstruction downgraded,” Ahmed says.

By then, Ahmed was serving as Chairman of the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), which he also helped to set up. He left ERRA in 2010.

“We ran the most successful reconstruction programme in the world according to the multilateral banks,” says Ahmed today. He points to housing as the biggest success and the quality of reconstructed roads, bridges and government buildings. “We could not do the same after the 2010 floods. Everything fell by the wayside. We’re not even talking about learning from others. We could not even replicate [what we knew]. The government wasn’t interested,” he says.

***

In 2009, ERRA’s chairman wrote to prime minister Yusuf Raza Gilani requesting that ERRA be abolished since it had completed its three-year mandate.

“To our amazement and surprise, the summary [we sent] came back saying ‘ERRA has done a great job so we want you to keep working’,” says the senior official.

Curiously, the government that did not want to fund ERRA made it a permanent entity through an act of parliament.

“There’s no reason why after three years there should have been a separate bureaucracy for earthquake reconstruction,” says MacLeod. ERRA’s responsibilities should have been transferred to NDMA and sub-national government departments.

In 2013, Nawaz Sharif wrote to ERRA stating that he “has been pleased to approve, in principle, the winding up of ERRA.” ERRA sits on 44 acres of land in Islamabad, which would be valuable if developed.

But the letter was moot. The ERRA can now only be abolished by parliament.

Today ERRA is a parking spot for officials who are in their last leg of service. “They are not interested in performing but in huge perks like high salaries, SUVs, utility bills paid by the government and servants at home,” says the current senior official.

“ERRA is paying less for reconstruction and more for maintaining [its] officials. It is a white elephant; an organisation without utility.” He estimates that the authority has 700 employees.

“Is this an army pet? Who is protecting ERRA? If they say they exist till their projects come to completion, then are their pending projects coming to completion?” asks Qazi.

The official says work is happening at the pace of a few schools a month. Frustrated donors have recently pulled back billions of rupees because ERRA could not get anything done.

Meanwhile in Pehlwan and hundreds of other communities in the quake affected region, children are studying in makeshift spaces, often in view of construction sites that should be their schools.

“Until we have a building, we can’t teach properly, there’s no place for the kids to sit. They don’t come,” says Hussain Shah, a teacher in Pehlwan who held classes in fields or people’s homes in his previous post because schools had not been rebuilt. “There should be checks and balances. Kindly request our government that they build our buildings quickly so that we can give kids better education,” says the teacher.

The writer is a Wilson Center Global Fellow.

She tweets @NadiaNavi

Published in Dawn, EOS, October 15th, 2017