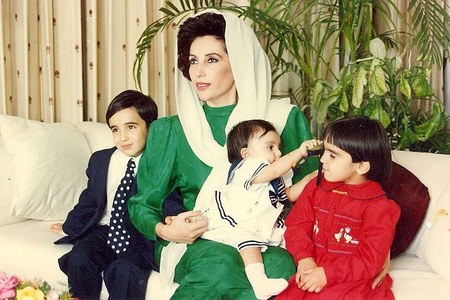

Special Report: Daughter of the East 1988-1990/1993-1996

The photograph above shows the indomitable Benazir Bhutto whose two tenures put together couldn’t add up to match the one that her father Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had at the helm of the country’s affairs. She started off on a bright note of symbolism, being the Muslim world’s first woman prime minister, but left behind a legacy that was not entirely unblemished. Though she adjusted her style of governance – not as much as she adjusted her headgear, as she is seen doing here – her best was still not good enough for reasons that were often, but not always, beyond her control. | Photo: Shakil Adil

Another Bhutto at the helm

By I. A. Rehman

BENAZIR Bhutto occupies a unique place in the political history of Pakistan. Twice elected prime minister of the country and the first woman head of government in any Muslim-majority state, she inspired the hope that she could put democracy back on the rails. Inability to fulfil this expectation dented her image somewhat. Allowed to complete neither of her two terms and hounded from one court to another for a long time, she was compelled to spend a decade in self-exile. Yet the establishment never stopped fearing her as a potential game-changer; a threat that could only be averted with physical liquidation.

Several factors contributed to her enormous popularity at the start of her political career. Young, charming and well-educated, she commanded sympathy across the land as the daughter of a former prime minister who many thought had been hanged unjustly. She had also won admiration for refusing to surrender to General Ziaul Haq’s autocratic rule despite cruel harassment.

Within 28 months of her return from self-exile, General Zia perished in a plane crash which removed a big roadblock on the path to democracy. Also during these months, she became the wife of Asif Ali Zardari, a marriage that was going to considerably affect her political career.

As the judiciary declined to restore the dismissed government of Mohammad Khan Junejo – though its sack by Zia was not upheld – and struck down the law on parties’ registration which endorsed party-based elections, the prospects for Benazir looked good. Also welcome was the flow of professional election fighters towards her Pakistan People’s Party.

However, there was no illusion about the task of return to democracy having been made extraordinarily daunting by the outgoing – and dead – dictator. He had transformed the form of government from parliamentary to presidential, and turned the state into a virtual theocracy. Above all, his Afghanistan policy had embroiled Pakistan in a many-sided crisis that was getting worse by the day.

The election to the National Assembly on November 16, 1988, did not give Benazir Bhutto a majority in the house, but her party emerged as the largest single group, having secured more seats (52) from Punjab than were won by the Islami Jamhoori Ittehad (IJI), an alliance clobbered by the establishment as a successor to the anti-Bhutto coalition of 1977 – the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA).

Three days later, apparently the establishment struck and did so most viciously by manipulating the provincial elections in Punjab to ensure that the IJI got more seats (108) than the PPP (84) and, thus, cleared the way for Mian Nawaz Sharif to become the chief minister of the politically most advantaged province. That effectively changed not only Benazir’s career but also the course of Pakistan’s history.

A Zia amendment had empowered the president to first nominate the prime minister before she/he could be elected by the National Assembly. President Ghulam Ishaq Khan did not name her as prime minister for nearly two weeks, until she had ceded to him and the military her authority in key areas, such as Finance, Defence and Foreign Affairs, especially Afghanistan. Yet she decided to take her chance.

![LIKE most of her predecessors, one of the things Benazir did on her elevation to the office of the prime minster was to visit Saudi Arabia to perform Umrah. | Photo: The Directorate of Electronic Media and Publications [DEMP].](https://i.dawn.com/primary/2017/11/59fc7eeaaa79c.jpg)

She started on a sound note, making a humanitarian gesture by offering relief to death row prisoners. She also strengthened her regime through alliances with the Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) for the stability of her government in Sindh, and with the Awami National Party (ANP) to bag the chief minister’s post in the North West Frontier Province (NWFP; since renamed Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).

However, preventing Nawaz Sharif from undermining her government soon became Benazir’s main preoccupation. The Punjab chief minister rejected the federal government’s choice for the provincial chief secretary’s post, tried to launch a radio station and decided to found a commercial bank. These steps converted the Punjab elite to the idea of provincial autonomy, an idea it had vigorously spurned when raised by the other provinces, especially East Pakistan that had been got rid of 16 years earlier.

Besides, working was not easy alongside a president who had little respect for the parliamentary system even though Benazir had swallowed the bitter pill by proposing him for a five-year term as president. He contested her right to have a say in making important appointments, and often choked the government by simply sitting on the papers sent up to him.

Adding to her worries were quite a few other problems. The Balochistan assembly was dissolved on the advice of chief minister Zafarullah Jamali as he was not sure of his majority in the house, but Benazir’s inability to set matters right before the high court restored the assembly shifted the blame on to her. Further, Benazir was not found good at retaining the goodwill of her allies. The break with MQM was no surprise as the pact with it was unworkable and the party had been seduced by Nawaz Sharif and their common benefactors. The alliance with ANP, too, was difficult to sustain but the efforts to save the Sherpao ministry in the NWFP did not add to the prime minister’s credit.

The break with MQM was followed by a surge in violence in Karachi and Hyderabad. The Pucca Qila incident became a sore point for both sides. While dealing with Sharif’s challenge, the government clearly took an exaggerated view of its capacity to tame a rich provincial chief being backed by the establishment. Before Benazir completed her first year in office, the opposition tried to dislodge her through a no-confidence motion that was taken up on November 1, 1989, and was defeated. However, the differences between the prime minister and the military on the one hand, and between her and the president on the other could not be resolved. On August 6, 1990, the president dissolved the National Assembly and Benazir ceased to be prime minister after barely 20 months in office. The charge-sheet against her included allegations of making the National Assembly dysfunctional, ignoring responsibilities to the federating units, lawlessness in Karachi, ridiculing the judges, and corruption.

In view of the appointment of opposition leader Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi as the caretaker prime minister, Benazir had little hope of winning the elections that were held three months later. In fact, her wait lasted three years when she came to power again after the October 1993 elections, which were held after president Ishaq and prime minister Sharif had knocked each other out.

Once again her party emerged as the largest group in the National Assembly. With the help of the Junejo faction of the PML and some independents, Sharif’s party, the PML-N, was denied power in Punjab as well. Soon after her trouble-free election as prime minister, her nominee, Farooq Leghari, was installed in the presidency. She felt far more comfortable at the helm of affairs and more powerful than she had ever felt earlier.

She began asserting herself by getting the PML-N ministry in the NWFP, led by Sabir Shah, suspended and governor rule imposed. The move was struck down by the Supreme Court. Then she set about changing the composition of the superior judiciary apparently to tame it and the subterfuge was quite unconvincing. This became the subject of a bizarre reference to the Supreme Court by president Leghari that the prime minister bitterly opposed. Eventually, Justice Sajjad Ali Shah, her controversial choice as chief justice, pronounced a judgment in what is now called the Judges’ Case that negated all her work.

The other main developments during this term included a failed attempt to oust Punjab chief minister Manzoor Wattoo of PML-J; Sufi Muhammad-led uprising in Malakand for Shariah rule; a huge increase in killings in Karachi; a hike in terrorist attacks; and sectarian violence. Stories of corruption involving Benazir and Zardari also gained currency at an uncomfortable pace. The allegations, even if not proved in courts, clearly reduced the prime minister’s popularity and credibility in equal measure.

Murtaza Bhutto’s return home and his arrest caused Benazir an ugly split with Begum Nusrat Bhutto, and his death after an encounter with the police dealt a severe blow to her government. Eleven days after the incident, on November 5, 1996, the president dissolved the National Assembly and Benazir was again out of power. The charges against her were Karachi killings (though the number had fallen by around 75 per cent from the 1995 figure), disregard for federal institutions, ridiculing the judiciary, and corruption.

As subsequent events showed, this was the end of Benazir’s role in the country’s government though she remained active in politics till an assassin’s bullet silenced her for ever near the place where the country’s first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, had been shot dead in a conspiracy of another kind.

Benazir Bhutto’s positive work as prime minister included giving the government a humanitarian face. The commutation of death sentences to life imprisonment was followed by banning of lashing (except for Hadd cases) and public hanging. The plan to offer the disadvantaged relief through special tribunals did not work, so a separate ministry of human rights was created. Her effort to amend the procedure in blasphemy cases was scotched by the conservatives, but her instructions not to arrest any accused without a proper inquiry did lead to a fall in such cases.

Women activists complained that she didn’t do anything substantial for them, but they could not deny the favourable ambiance Benazir had created. And her uncompromising resistance to pseudo-religious militants was not matched by anyone, with the possible exception of Afzal Lala of Swat.

The hurdles that held Benazir back included the absence of a culture of democracy; the habit of political parties to treat one another as their worst enemies and a tendency among them to destroy political rivals with military’s help; the personality cult in the PPP and its centralised decision-making without democratic centralism; and the politicians’ failure to remember that what was not permitted to authoritarian rulers was prohibited for them too.The PPP also suffered as a result of its shift away from a left-of-centre platform as it blunted the edge it had over the centrist outfits.

An assessment of Benazir Bhutto’s prime ministership usually takes two forms: one, that she was incapable of establishing a democratic order, and, two, that the establishment did not let her work. A realistic view will begin by noting the absence of a stable, efficient and fair-minded state apparatus that could relieve her of routine chores and allow her to concentrate on broad political and socio-economic issues.

Also, no politician could (or can even today) roll back the Zia legacy through a frontal attack, except for a popular revolution. Besides, the deeply entrenched, highly trained and generally better informed establishment needed to be outmanoeuvred in a subtle and adroit manner. Benazir Bhutto was outmanoeuvred by the dominant power centre and she might also have sometimes unwittingly helped it.

The real losers as a result of Benazir Bhutto’s elimination from politics were the people. Their concerns remained off the government’s agenda and the dream of a democratic and egalitarian Pakistan receded even further.

The writer is a senior political analyst and human rights activist.

This story is the tenth part of a series of 16 special reports under the banner of '70 years of Pakistan and Dawn.' Visit the archive to read the previous nine reports.

*HBL has been an indelible part of the nation’s fabric since independence, enabling the dreams of millions of Pakistanis. At HBL, we salute the dreamers and dedicate the nation’s 70th anniversary to you. Jahan Khwab, Wahan HBL.*

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

The fun never really ends

By Owen Bennett-Jones

FOREIGN correspondents reporting on Pakistan fall into two categories. Some are infuriated by the doublespeak that so often emanates from Pakistan officialdom. “How dare you,” the Foreign Office used to ask in outraged tones, “even suggest we are building a nuclear bomb?” And there were those vehement denials of involvement in Kargil. “We are not there!” the Army insisted, even when the world knew they were. And today? “The Haqqani Network? Nothing to do with us.”

While that sort of thing drives some correspondents to the airport, others at least appreciate the charm with which these diplomatic untruths are delivered. And from a journalistic point of view, there are mitigating circumstances. Pakistan produces so much news. With violent jihadis, nuclear bombs, the drugs trade, insurgencies and endless amounts of vivid colour stories, it is impossible to be short of things to write about. And there’s something else. Put a microphone in front of a Pakistani and the mildest mannered individual will, at a moment’s notice, turn into an impassioned political activist proclaiming the virtues of his or her political hero whilst despairing about the venal corruption of everyone else’s. It’s all great copy. Cynics might say that the politics of Pakistan have the quality of a soap opera in which the lead characters – and their offspring – vie for power in a largely pointless competition between self interested, grossly wealthy, elitist egos. Maybe. But it’s fun to watch.

And the press itself has had a tumultuous history filled with large characters, great courage, high principles and low venality. In the early days it was all about Ayub Khan’s battles with the Pakistan Times. It was also an era when people all over the country turned to BBC Urdu as a source of impartial news. As for television, PTV, for its first quarter of a century, enjoyed a monopoly that remained intact until two international channels, the BBC and the CNN, came onto the scene offering an alternative to the official view.

As the BBC Pakistan correspondent on the night of October 12, 1999, I experienced the somewhat terrifying responsibility that came with working for what, at the time, was probably the most trusted news source in the country. PTV, always weakened by the need to reflect the views of the government, was further disabled by being caught between two authorities – the government and the Army. CNN did not have anyone one on the ground. That left the BBC.

It began with a call from a contact in PTV saying that something was going on. The BBC cameraman and I rushed down to the station’s headquarters just in time to film soldiers climbing over the gates. In the old days feeding such pictures to London would have been impossible without the cooperation of PTV which, in the circumstances, would not have been forthcoming. But using a primitive form of internet transfer software we managed to get the pictures sent. However, that was just the start of my problems. Within a few minutes I was live on the BBC being asked: “Is it a coup?”

Rumours of an Army takeover were spreading all over the country. People were tuning to the BBC to get an authoritative version of what was happening. If I called it wrong, the BBC would never live it down. When I arrived in 1998 people were still complaining about what they believed was a false BBC report about the Indian advance on Lahore in 1965. Could it, I wondered, be something less than a coup? An action to arrest the head of PTV perhaps or seize some film? A holding operation of some kind? How to be sure?

“Soldiers have climbed into PTV,” I hedged. “I can’t say it is a coup but it certainly looks like one.” And then some anxious minutes to see if even that rather mealy-mouthed version of events stood the test of time. That was only 20 years ago but already those days seem like ancient history. General Pervez Musharraf’s decision to enable the establishment of private channels transformed Pakistan’s media scene. It is often said that the military only agreed to the reform because India outdid them when it came to whipping up a war fever during the Kargil conflict. India’s private-sector channels had a clear, melodramatic edge over the rather stolid efforts of PTV. Whatever the Army’s true motives, the outcome has been remarkable, with a babble of news channels both radio and TV now churning out news in many languages 24/7.

The impression of media diversity, however, is illusory. The channels may compete for viewers but they air strikingly similar opinions. It’s free speech of a kind – but everyone knows the limits.

It was ever thus. Many of Pakistan’s military and civilian leaders have bribed friendly journalists and imprisoned hostile ones. Some have even, to put it generously, failed to stop journalists being murdered. For the politicians it’s normally a case of trying to prevent negative coverage. The soldiers see it slightly differently. The press, they believe, is a weapon to be deployed on the information frontline, serving the Army’s version of the national interest. But both the politicians and the military top brass do agree about one thing: journalists are, by and large, upstarts who should know their station and do as they are told.

The journalists – or at least an impressive proportion of them – have had different ideas. Even when General Ziaul Haq was describing the Karachi Press Club as “enemy territory”, many journalists responded by resisting authority. It was a difficult time. But the contest isn’t over yet. Whether its Geo’s 2015 allegations about the ISI or this year’s [Dawn story by Cyril Almeida], the state continues to draw red lines and the press continues to bump up against them.

So where does Dawn sit in this new media age? The last decade has seen a number of Masters and PhD students conduct content analysis of Pakistan’s newspapers. Having read half-a-dozen of these rather heavy going theses, I can summarise their conclusions: ‘The English language press is less sensational than the Urdu language press’. It may sound like a recipe for low circulation but dawn.com’s growing international readership suggests otherwise. Some Pakistanis may find Dawn a shade liberal but many readers abroad looking for an independent, reliable voice, see it rather differently.

The writer is a British journalist and author of ‘Pakistan: Eye of the Storm’.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

From sloggers to celebrities

By Sherry Rehman

IF there is one reality that defines Pakistan’s media consistently across seven decades, it is its commercially powered growth. In 70 years it has mutated in quantum stages to multiple levels. The pen that used to be mightier than the sword has become a nano-chip-powered lightsabre. Today the media is very different from the entity that lived and breathed through the printed word alone.

In the 1970s or ’80s, when I was struggling to find my voice, Pakistan Television monopolised the airwaves, and the print media’s message was refracted to literate, if not educated, elites. At that point, its power and scale were both at another platform. Despite being controlled and smaller in scale, the mission statement was about telling truth to power, not brokering it.

As we speak, in its new electronic or digital avatar, the media is inside our living rooms, our smart phones and our heads. It is often the persistent voice bombarding us with information overload and shrill opinion, or the quiet algorithm curating and culling what we read in the digital world. Not all the changed hard-wiring is entirely sinister, or a conspiracy to strip readers and viewers of choice and knowledge, but certainly a darker labyrinth to navigate.

It wasn’t always like this of course. The journey from newspaper to television to the social media, all vying for space in a crowded information environment took a few decades, but it brought the spectrum light years away from its vintage days as I like to call it. As a budding journalist myself in the pre-private channel days, I am grateful that a high learning curve was literally forced on one, as was the ability to build context and to try and locate the story behind the headline.

The political landscape was not complicated for those who spoke out or fought authoritarianism. After 1977, for 11 long years when General Zia dictated Pakistan’s big choices, despite the political darkness, the beacon-call of values confronted every decision. Every era demands its own clarity and courage, but to me this one felt like Pakistan’s darkest night. The line between political activism and professional journalism often blurred at the press clubs.

There was always tension between the media and government, the owner and the professional. Like any media in the world, Pakistan’s too always walked a tightrope between its mission statement and its business plan. There were many definitions of what the media was supposed to do. Yet in the moral universe we inhabited, outside the shadowy world of yellow or paid journalism, we all had rough agreement on one rule: that the media was supposed to be a watchdog for the public, holding both a mirror to society and making government answerable. To many of my heroes who plied the tradecraft, it was a calling, not just a smart career choice.

Much of that changed when two things re-defined Pakistan. One was controlled democracy, which as a form of government was restored in 1988, but remained hostage to a strong civil-military establishment axis that still wielded constitutional power to dismiss elected governments. This dynamic by itself changed the nature of the state’s relationship with the media. As governments eased back on restrictions, cacophony often replaced checked content. In the best cases, courageous rites of confrontation with dictator-led regimes were replaced by investigative but also other less robust types of mainstream reporting. Largely, in the absence of publicly shared facts, as covert policy-plays and information famines became the norm, the media reports that gained most currency were the ones that predicted different outcomes. In this context of serial uncertainty, the media changed. It became a site for endless speculation which it has refined to a lesser art to this day.

The other big change that re-tooled the Pakistan media was the opening up of the licensing regime for the air waves which broke the state monopoly on television with permissions to air for the BBC, the CNN and a local private channel. These baby steps should have heralded incremental change, which would have perhaps tempered growth with quality. Instead, another dictator, this time Pervez Musharraf, in an attempt to buy favour with the media, opened the floodgates to TV channel licenses without regulating the business. Media houses that could once only run a few newspapers grew into cross-media juggernauts, empires that small independent media could not hope to challenge for resources. Flash celebrity journalism replaced the daily slogger. In the space of one decade, Pakistan’s media turned into a huge window of social and political churn.

While remarkable changes in Pakistan’s media have transformed its vast axis and peripheries, to my mind, at its core sits the professional journalist, who still fights a daily battle for survival. From the dangers of frontline reporting, both in traditional war zones and complex urban battlegrounds, Pakistan’s battle against violent extremism has re-set the terms journalists have to ply. Thousands of journalists have become a statistic in the roll-call of silenced voices.

Ironically, high risk has brought with it a new breed of valour. With self-censorship in such a predatory, unprotected environment where the battlefield can be anywhere, the truth could have become a terrible, endangered casualty. But it hasn’t, because the urge to out the real story behind the muffled one still excites many journalists. Today the bodycount and bloodspill of the Pakistani media ranks high in international metrics for professional bravery. Counter-intuitively, the fragility of a life in journalism is much higher than it was in times where the state was the only repressor.

At no point in our history, though, was any media house a temple to abstract virtue. In the pre-television days, the media was often or primarily a business, and, equally, a bargaining chip for power. Yet even as a commercial venture, or pathway to power, the proprietor, as the owner was known, was conscious of the nature of the business. It was never a widget or tool-factory. The newspaper traded in ideas, information, and, at best, knowledge. It had to embrace values or reject them every single day. Ethical, moral choices over what to print, or what not to print, defined a professional’s daily universe.

The choices are made even today, except with a difference. Today, unlike before when policy was a yearly discussion between editor and owner, the new normal for red lines between the executive and editorial have totally blurred. The average proprietor sets the daily terms of engagement for news content. Exceptions, like the Dawn, maintain separation of powers, but largely the owner-editor is a phone line away, where advice from various places informs output.

Global trends don’t help. A new frontier of alternative facts and ‘post-truth societies’ set at least my teeth against the digital leash that allows truth to become real just because it is repeated enough. But hope, like data, springs eternal. The good news is that the truth like this cliché, is always out there, even if only in analogue reality, and there are journalists who clearly know that it must not become fungible like money. A story or news show may spurt its froth, but the core will find its hydraulic way to the surface, even if it is coloured.

The dangers of modern-day televangelism, though, is a whole different op-ed.

The writer, a Senator, is former editor of the Herald, and has served as Pakistan’s Information Minister and Ambassador to the USA. She is Chair of the Jinnah Institute and Vice-President of the Pakistan People’s Party Parliamentarians.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Tenure I: 1988-90

***

ISHAQ ELECTED PRESIDENT, BENAZIR CONFIRMED AS PM

DAWN December 14, 1988 (Editorial)

A vote for change and continuity

SOME of the uncertainty in the present political set-up has been removed by the election of Mr Ghulam Ishaq Khan as President and the confirmation of Ms. Benazir Bhutto, through a vote of confidence, as Prime Minister of the country. The vote in either case was more than convincing. The constitutional requirements that had to be fulfilled following the dismissal of the earlier Assemblies and the death of General Ziaul Haq have thus been completed. The President had to be elected within 30 days of the elections to the National Assembly and the Prime Minister had to get a vote of confidence from the same body within 60 days of his or her nomination to that post. All this having been satisfactorily done, the country and the Government should now be in a position to turn their backs upon the past, and its share of bitterness, and look forward to the tasks that urgently await tackling. It is fairly obvious that there is mixture of continuity and newness in the composition of the present governmental structure – the continuity being symbolised by the person of the President and the newness by the Prime Minister. The present situation is accordingly both a continuation and a modification of the past – and not, it bears remembering, a complete break with it. Mr Ghulam Ishaq Khan brings experience to his post. In fact, his election comes as the crowning event of a remarkable career. He has had a ringside seat at all the important changes that have taken place in the country for the last 20 years if not more. Ms. Bhutto for her part brings a sense of daring and innovation to her position.

Complementing each other’s role, the two can keep the ship of state on an even course. In this connection, it is worth bearing in mind the tensions between President Zia and Prime Minister Junejo and where these eventually led.

It hardly needs any emphasising that Pakistan is on the threshold of a great opportunity. Given a semblance of good sense and goodwill, the foundations of democracy can be strengthened and the recurrent nightmare of military rule can be prevented. But if greed and unprincipled ambition are to be the portion of our national politicians, then the only thing they will be doing is to tempt the furies watching from the wings. Care, caution and moderation should be the watchwords at this hour. Other things can come in their own good time.

***

PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLY DISSOLVED

DAWN December 18, 1988 (Editorial)

The crisis in Baluchistan

THE wave of euphoria which the PPP was riding since the assumption of power has been cut short by the crisis in Baluchistan. The Governor quite emphatically has said that once he had received advice from the Chief Minister to dissolve the Assembly he was bound to act accordingly and that he was under no obligation to inform either the President or the Prime Minister about his proposed course of action. That may be the strict constitutional position but it still begs several questions. Given the controversy surrounding the election of Mr. Zafarullah Jamali as Chief Minister, should not the Governor have taken some time to weigh the advice tendered to him by the Chief Minister, instead of acting so precipitately at such an unearthly hour of the night? At any rate, pure legalism aside, the Governor, with no small help from the beleaguered Chief Minister who was increasingly finding it difficult to cobble together a working majority in the Baluchistan Assembly, have triggered a political crisis with grave implications for the country.

***

BENAZIR FIRM ON ACTION

DAWN December 30, 1988 (Editorial)

The drug menace

DRUG trafficking poses one of the most daunting problems that the new democratic government must address. The commitment to deal with the drug issue on a priority basis was made by the Prime Minister [Benazir Bhutto] in her first news conference. She also announced that she would set up a ministry of narcotics control to curb drug trafficking. The drug underworld flourishes more easily in authoritarian societies. It is impossible to deny the fact that the drug problem rapidly assumed menacing proportions during the past seven or eight years.

According to official estimates, Pakistan now has 1.9 million addicts and more than 650,000 of them are hooked on deadly heroin. Unofficial figures are a lot more scary. Likewise, foreign experts estimated that narcotics worth $3.5 billion had been smuggled out of Pakistan in a year. Recent reports have indicated substantial increase in the country’s poppy production – so much so that the prices of narcotics fell in the tribal area.

***

BENAZIR, RAJIV HOLD TALKS

DAWN January 3, 1989 (Editorial)

A good beginning

AFTER the freeze in the troubled relations between India and Pakistan which lasted quite a few years, we are witnessing the first signs of a thaw. There has been a major display of diplomatic purposiveness at the level where it counts. The talks between Prime Ministers Rajiv Gandhi and Benazir Bhutto which were held in a cordial and even an upbeat atmosphere have been followed by the conclusion of three agreements. As both leaders stressed more than once during their joint Press conference, these are the first agreements between the two countries since the conclusion of the Simla accord – a gap of 16 years. Mr Rajiv Gandhi’s trip of Pakistan was also the first by an Indian Prime Minister for 28 years. There is thus a sense of expectation on both sides, fuelled in no small measure by the accession to power of a democratic government in Pakistan. That democratic governments can get along better with each other is, however, an assumption that has yet to be proved right empirically. But it need not be dismissed out of hand either. If for any reason time is wasted, the present momentum can soon peter out – which will be a pity since the stars appear to be more favourable for breaking the logjam in India-Pakistan relations now than at any time during the last two decades.

All the same, expectations need to be kept in some sort of a check since euphoria can be as dangerous a state of mind as morbidity or paranoia. A change of leadership alone, while it may be important in its own way, is by itself an insufficient basis for a dramatic improvement in ties between two countries as pock-marked by suspicion and conflict as those between India and Pakistan.

The obvious difference in the two countries’ positions on Kashmir came out clearly. Afghanistan also is a point of friction. Although a conducive atmosphere can help promote the chances of a settlement between the two countries, hard and patient negotiations lie ahead before there can be progress in areas of greatest disagreement. If expectations are unrealistic at this stage, the mood could quickly sour if progress is inordinately delayed. But meanwhile there must be the satisfaction that a good beginning has been made.

***

NAWAZ SAYS HE CAN’T BE DISLODGED AS PUNJAB CM

DAWN March 10, 1989 (Editorial)

A showdown can yet be avoided

THE crisis between the Federal and Punjab Governments has now exploded in full public view. In retaliation for the IJI dissidents’ PPP-inspired move to table a no-confidence motion against Mian Nawaz Sharif, the IJI leaders plan to move a motion in the National Assembly expressing lack of confidence in the Federal Cabinet. Normally, a no-confidence move against a Cabinet in a parliamentary system is very much a part of democracy’s drill; it is not something to look askance at. Democracy in this country is still like a tender sapling. It needs to be nourished with loving care and gaurded against inclement weather, so that it can grow into a powerful tree. It is therefore best if the coming showdown is called off and a new beginning made towards an adjustment arrived at in the spirit of honouring the popular verdict.

***

MQM’S ULTIMATUM

DAWN May 3, 1989 (Editorial)

Crisis in Sindh

WITH the resignation of the three Mohajir Qaumi Movement ministers from Sindh Cabinet in the wake of the alleged three hour ‘house arrest’ of the MOM chief, Mr Altaf Hussain, in Hyderabad on Saturday [April 29], the political and ethnic situation in the province has taken a turn for the worse. On Sunday evening, the MQM Chairman, Mr Azeem Tariq, gave the PPP Government 24 hours to dismiss the Hyderabad administration, failing which the MQM ministers would be withdrawn from Sindh Cabinet. While the ultimatum was duly carried out in spite of ongoing negotiations between the two parties, the possibility of a patch up has been left open by the assurance held out by the MQM Chairman that the PPP MQM accord known as the Karachi Declaration would remain intact and that the MQM would continue to support the PPP in the National Assembly.

***

NO-TRUST MOTION AGAINST PREMIER FAILS

DAWN November 3, 1989 (Editorial)

Giving sanity a chance

NOW that the voting on the no-confidence motion against the Prime Minister has passed off peacefully, can a somewhat bemused nation expect some respite from its leaders and politicians? From both sides certain excesses may have been committed. Certainly, it would have been much better if the enforced sightseeing in Murree and Mingora had been avoided. Calling upon the Army to help keep the peace in Islamabad was also somewhat unnecessary. But all said and done, it was almost anti-climatic how peacefully events passed off in Islamabad on November 1. This difficult episode having now peacefully concluded, the nation has a right to expect that some of the passion rocking the political arena would subside and that leaders on both sides of the divide would take stock of the situation calmly and turn their attention to the myriad problems facing the country.

The events of the last 11 months, let alone the last 10 days, have gone a long way to demonstrate the innate solidity of the split verdict of the November elections. All efforts to upset this arrangement, ordained by the collective wisdom of the people of Pakistan, have failed. It is high time, therefore, that this basic fact was accepted.

This does not mean that the Government should cease trying to broaden its base or that the Opposition should stop opposing the Government. Healthy controversy and sharp debate are the very essence of democracy. But it does mean that both Government and Opposition should conserve their energies for worthier purposes. So far we have had plenty of horse-trading, but not much of policy formulation. No wonder, Parliament has passed hardly any new legislation during the last 11 months. Pakistan cannot afford any more of this drift. It is the Federal Government which must give the lead in pulling the nation towards some worthwhile objective. Which is reason enough, therefore, for the Federal Government to avoid divisive and controversial policies like the People’s Works Programme or the induction of lateral entrants into the civil service. It is also scarcely advisable for the Federal Government to open new war fronts in every direction. The simmering controversy over the appointment of senior judges can still be avoided. If this passion for tilting at windmills was curbed, there is no reason why the sun should not shine on Pakistani democracy.

***

JATOI NOT TO MEET PRIME MINISTER BENAZIR

DAWN January 11, 1990 (News Report)

COP seeks Ishaq’s intercession

THE Leader of the Combined Opposition Parties (COP), Mr. Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi, said here [Islamabad] on Wednesday [January 10] that during a meeting of the Opposition leaders had with the President, Mr. Ghulam Ishaq Khan, the Opposition brought to his notice a host of complaints against the Federal Government and sought his intercession on their behalf.

At a Press Conference after the COP’s 90-minute meeting with the President Mr. Jatoi said, “the President just listened to us”. However, an official Press release from the COP leaders stated that the President “emphasised the need to settle differences through talks.”

The official Press release said the President expressed “the confidence that the legislators would follow a legal, constitutional and democratic path to sort out their differences”.

At his Press conference, Mr. Jatoi said that the COP leaders believed that the Federal Government had been harassing the Opposition and started a “regular witch-hunt” of all those who were opposed to the People’s Party.

The President was informed of the alleged abuse of Governmental powers and funds by the Federal Government.

The COP leader promptly said, “No”, when asked whether the Opposition would be willing to meet the Prime Minister if she invited the Opposition over. He, however, added after a pause that any such invitation would be discussed by the COP whether to accept it or not.

He rejected a suggestion that the COP leaders should make a move to meet the prime minister directly to discuss their complaints and said, “We will not meet her: it was her duty to do justice”.

***

CHAOS AND CLASHES

DAWN February 7, 1990 (Editorial)

The drift in Sindh

TENSION and violence stalk Sindh once again. The riot that erupted in Hyderabad and later spread to Nawabshah was contained. But its fallout seems to have affected Karachi with a sudden and phenomenal increase in acts of violence. These included shootouts among student groups, kidnappings of and by students belonging to APMSO and PSF, and attacks on homes of MQM and PPP activists, including three provincial Ministers, besides sniping by unidentified men riding cars. One comment can be made safely: the parties involved have continued to maintain a stance of eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation. Each day’s newspapers are full of allegations and counter-allegations by PPP and MQM blaming each other for the crimes they might or might not have committed. Surely this is not the way in which political forces are supposed to conduct their contest and sort out their differences within a national framework. However, in the kind of politics we are witnessing is Sindh — politics in which no holds are barred — how can one expect positive results?

All those politically engaged in Sindh must ask themselves whether it is wise and proper to let political polarisation continue.We are not asking straightway for a political reconciliation, for that is hardly realisable in the immediate context. But it is certainly possible for the two parties to resume communications for the limited purpose of managing the crisis and preventing it from spilling over into the domain of inter-ethnic relations.

***

ARMY CALLED OUT IN KARACHI, HYDERABAD

DAWN May 28, 1990 (Editorial)

Aspects of the crackdown

THE Sindh Government’s long promised crackdown on ‘criminals’ and ‘terrorists’ has finally begun. So far, more than 1,000 persons considered to be outlaws, suspects and their collaborators have been rounded up in swoops made throughout the province. An unfortunate offshoot of the crackdown is the situation in Hyderabad. In clashes between security forces and people variously described as terrorists by the Government, and innocent citizens by the Opposition, dozens of people have been killed. There have also been unconfirmed reports of some policemen looting some shops in Hyderabad and committing other excesses. Undeniably, the law enforcement agencies’ task is difficult in a situation of blind antagonism and distrust between groups opposed to each other.

Evidently, many of those wanted by the authorities got wind of the imminence of the operation and managed to make good their escape. Quite a few must have been provided sanctuary by the influential people who have always shielded them. As for foreign agents directly referred to by the Prime Minister only the other day, none has been caught so far. This failure is greatly to be deplored.

It is difficult to say who is the victim and who is the oppressor, and whether the conductors of the anti-terrorist raids are observing the necessary restraint and impartiality, making sure that innocent people are not victimised. Much of the agony the people have endured could have been avoided if the Government had acted earlier and not now when so much blood has already flowed, so many deep wounds caused and such colossal sufferings inflicted upon the people. This has been an unpardonable failure, no matter what the technical, administrative or other explanations are.

***

BENAZIR SACKED, EMERGENCY DECLARED

DAWN August 8, 1990 (Editorial)

A step forward or a step back?

THE dissolution of the National Assembly and the dismissal of the Bhutto Government brings to an end another chapter in Pakistan’s tumultuous history. It was not wholly unexpected since the country at large, and Islamabad especially, had been seething with rumours for the last two or three months about some action against the Federal Government. In the event, Mr Jatoi’s declaration that the Combined Opposition Parties would move another motion of no confidence in the National Assembly was little better than a smokescreen for the real action being prepared behind the scenes: the outright dismissal of the National Assembly and the PPP-dominated provincial assemblies of Sindh and the Frontier province. The reasons for this action are enumerated point by point in the President’s dissolution order — reasons which the President amplified further in his address to the nation. Be that as it may, there is no getting round the fact that the outgoing Federal Government had accumulated rather a grim record for itself. Its working was impaired by a considerable amount of immaturity and an inability to focus on the real issues facing the country. The widespread aura of corruption that came to surround it did little to improve its image. Putting the events of this summer together it seems hard to escape the suspicion that the triangular relationship between the army, the President and the Prime Minister had broken down.

***

Tenure II: 1993-96

***

BENAZIR SWORN IN AS PRIME MINISTER

DAWN October 20, 1993 (Editorial)

Ms Bhutto’s game to win or to lose

IT used to be a rule of Pakistani politics that when the country’s prime ministers were removed from office they were removed for good, never to return. It is a rule that no longer holds because Ms Benazir Bhutto has just become the first Pakistani politician to be returned to the prime ministership twice. This is a tribute both to her own determination and skill as a leader and to her party. Among all the bad things that can be said about Pakistani politics this transition is a happy development. But several other things continue to fuel a sense of concern. Since Ms Bhutto is presiding over a coalition dependent for its survival on the support of independent MNAs, it is only natural to wonder how strong it will be. Will it be able to look ahead or will its attention be distracted by the need to keep itself afloat? We will have to wait and see.

It is true that many needless mistakes were committed by Ms. Bhutto’s first government in 1988-90. But it is also true that it was operating in a hostile environment, with both the president and the army chief looking upon it with barely concealed hostility. Those hostile factors are no longer in play. This game is, therefore, Ms. Bhutto’s to win or to lose. If she gives a sense of direction to the country, she will earn the abiding admiration and support of the people. If she once again loses her way, she will have no one to blame but herself.

***

A JUDICIARY INDEPENDENT OF THE EXECUTIVE

DAWN November 2, 1993 (Editorial)

Separation at last?

THE government’s quick response to the Supreme Court’s directive that the judiciary be separated from the executive by March 23, 1994, holds out the hope that one of the most abominable legacies of the colonial rule would finally be done away with. The issue has had a chequered history, with successive governments making solemn vows to give the judiciary complete independence at all levels, and then doing nothing to honour them.

It is reassuring, therefore, that the government has finally decided to do what should have been done long ago. The law minister says that preliminary work for the separation of the judiciary and the executive has already been initiated and the objective shall be achieved by the stipulated date. However, any mood of celebration on this score must be held in check until the process has been fully and finally carried out.

***

LEGHARI BEATS SAJJAD BY A WIDE MARGIN

DAWN November 14, 1993 (Editorial)

A new President

THIS was a straight contest between the PPP nominee, Sardar Farooq Leghari, and the choice of the PML(N), the acting president Mr Wasim Sajjad. Even so the PML(N) might not have been prepared for the wide margin with which Mr Leghari has won — getting 274 electoral college votes to Mr Wasim Sajjad’s 168. For the first time since General Ziaul Haq twisted the 1973 Constitution, there is harmony between the offices of the President and the Prime Minister, with both the incumbents belonging to the same political party. This gives rise to the certainty that the nation would be spared the kind of conflict and confrontation which ever since 1988 lent Pakistani politics the aspect of a tribal battlefield. Harmony between these two highest offices of state also takes much of the sting out of the Eighth Amendment which, of course, is not to say that the government should not think of amending this queen of amendments.

***

A SPLIT AT THE TOP OF THE RULING PARTY

DAWN December 7, 1993 (Editorial)

PPP’s leadership crisis

IT was no secret that Begum Bhutto and her daughter the Prime Minister did not see eye to eye an the question of Murtaza Bhutto’s entry into national politics. But after Ms Benazir Bhutto’s elevation as chairperson of the PPP the split at the top of the party has been sealed, with the break with Begum Bhutto now complete. The resolution passed by the PPP Central Executive Committee (CEC) does not say what hay happened to Begum Bhutto’s chairmanship but it is clear that she has been unceremoniously removed, the CEC not bothering to pay her even a perfunctory tribute. In the events leading to this break Begum Bhutto behaved more like a mother than an elder statesperson. In the recent elections she campaigned on her son’s behalf against the party’s nominees. This would obviously not have gone down well with Ms Benazir Bhutto who considers herself the rightful heir to her father’s political legacy.

***

NUCLEAR PROLIFERATION IN SOUTH ASIA

DAWN December 17, 1993 (Editorial)

Pressler’s logic

THANKS to his famous amendment, Senator Pressler is a widely known if not a household name in Pakistan. Senator Pressler says that both India and Pakistan are ready for the inspection of their nuclear facilities. Whether India really is or not we do not know but about Pakistan’s willingness to have its nuclear facilities examined there should be no doubt, provided only that the standards applied to Pakistan are applied to its giant neighbour as well. In fact, Pakistan’s whole case about its nuclear programme rests on this desire for parity. And this precisely is the central flaw of the Pressler logic. Responsible people in the United States are beginning to recognise how the insecurity bred by the Kashmir dispute has fed the arms race between India and Pakistan. But this linkage seems to escape Senator Pressler’s mind. By signalling its willingness to do away with the Pakistan-specific language of the Pressler amendment, the Clinton administration is on the right track.

***

FRAUD IN HIGH FINANCE AND POLITICS

DAWN April 22, 1994 (Editorial)

The Mehrangate scandal

MR Yunus Habib’s colourful career up the banking ladder is another reflection upon the sorry state of high finance and politics in Pakistan. Can we do nothing right and must fraud be an integral part of all our endeavours? Going by the revelations flowing thick and fast from the affairs of the Mehran Bank, it is clear that Mr Yunus Habib was running about the most corrupt bank in the country. The list of people whom he lent or rather gifted money is impressive and if the worst rumours are to be believed, this list reaches from one side of the country’s political divide to the other. And what Mr Yunus Habib reportedly got in return were favours which enabled him to sustain his buccaneering bank for so long. Jam Sadiq Ali, one of his great benefactors, was instrumental in getting many official accounts transferred to the Mehran Bank’s coffers. But Jam Sadiq’s successors saw to it that this practice was continued.

But the question that must bother amateur detectives is as to what possessed the ISI, the country’s premier intelligence agency, to deposit its foreign account with Mehran Bank? Did the ISI’s masters have no inkling about the things that were going on in Mehran Bank? The greed or foolishness of politicians is taken for granted by the ordinary people of this country. But that the knights of the ISI should have allowed themselves to have been taken for a ride in this scandal is a more serious matter. Which brings us to the question of General Aslam Beg’s involvement in this scam. What was he doing taking huge amounts of money from Mr Yunus Habib? And where did he spend this money, on his person or for some other dark purpose? General Beg has certainly done no service to the high office which he held in the past. Many of his activities as army chief were already the subject of public controversy. The latest revelations only confirm the impression spread by the earlier stories. The least that can be said about him is that he should explain his position to the nation.

As it is, public standards of morality have plunged drastically. This is a chance to retrieve the situation to some extent or at least to make a fresh beginning.

***

MQM AND THE HAQ PARAST FRATRICIDE

DAWN August 11, 1994 (Editorial)

Murder for murder

THE mafia-like infighting between the two factions of the Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) has for the past several months been taking a heavy toll of human life — and the end is not yet in sight. Reports of the wanton killings in all their gory details have been appearing with nauseating regularity in the Press and there is not the slightest doubt that a spirit of vendetta is at large. Violence, sometimes in its most heinous form, is seen as the only means of settling political scores. Gunfights on the streets, aimed at eliminating activists of the rival faction, take place every now and then, and not unoften innocent persons get caught in the cross-fire. One understands that the differences between the mainstream MQM, which apparently commands a strong mass support, and its breakaway faction, the Haqiqi, are irreconcilable with neither being inclined to consider the possibility of restoring organisational unity. What is incomprehensible is that elements in both factions should demonstrate an utter lack of concern for human life and the misery and sorrow which inevitably follows vendetta killings. The bloody feud is destroying what remains of the peace and contentment of a distraught city and adding tremendously to terrible sense of insecurity to which its unfortunate citizens have been condemned. A most bewildering aspect of the present situation is that the fratricidal conflict is taking place at a time when there is a strong presence of law enforcement agencies in Sindh, particularly in Karachi, and the Operation Clean-up, has been under way in the province for more than two years.

***

MORE MILITIA FOR THE PROVINCIAL CAPITAL

DAWN June 19, 1995 (Editorial)

As Karachi burns & bleeds

THE truth is that while Karachi is being devastated by violence and strife, those who control the destiny of this metropolis are safely ensconced in their ivory towers, hundreds of miles away, busy scoring points against one another. The decision makers in Islamabad, the opposition leaders and the MQM leadership in self exile in London, all of whom have contributed to Karachi’s tragic plight, have not deemed it necessary to visit the city and see for themselves the havoc their misguided policies and actions have wreaked on it. Their favourite pastime is to blame each other for the crisis. Describing the situation as an insurgency staged by terrorists, the government has chosen to counter it with force. That is why more forces are to be inducted into the city. Constabularies from Punjab and the Frontier and Baloch militias are to be brought in to put down the ‘rebellion’. Such administrative measures without any concurrent political move for conciliation can be disastrous. These units are not trained for law enforcement duties in densely populated urban areas. Mary of them would not even be familiar with the environs of Karachi or the language and culture of its people. It is very likely that they will perform their assigned task in a manner that would make a messy situation only messier and more intractable.

***

MAJ-GEN ZAHEERUL ISLAM, OTHERS ARRESTED

DAWN December 21, 1995 (News Report)

Army officers face coup charges

THE four senior army officers, arrested for conspiring to storm a corps commanders’ meeting in Rawalpindi to stage a bloody coup, have been charged with waging war against Pakistan and attempting to seduce persons from their allegiance to the government, a Defence Ministry Press release said. Major General Zaheerul Islam Abbasi, Brigadier Mustansar Billah, Colonel Mohammad Azad Minhas and Colonel Inayatullah Khan were arrested in the last week of September for conspiring to kill the president, the prime minister and the army top brass to bring about an Islamic revolution in the country.

The accused, to be tried by the Field General Court Martial, would be given an opportunity to nominate their defending officer from the army as well as defence counsel from the civil of their own choice. The officers were being allowed regular meetings with their family members. No date has yet been fixed for trial. The court, headed by a major general, yet to be named, will have four senior officers of the rank of brigadiers and colonels as its members.

***

MURTAZA KILLED AS GUARDS, POLICE EXCHANGE FIRE

DAWN September 22, 1996 (Editorial)

A tragedy that should not have happened

MIR Murtaza Bhutto’s killing is a tragedy for his family which over the years has had more than its share of suffering. The father reaching the heights of political authority and leaving his stamp on the country’s politics and then losing his life on the gallows. The younger son dying in a far-off land in still unexplained circumstances. And now the remaining son brought down by a hail of police bullets when his own sister is ruling the country. Pity Begum Bhutto all the men in whose life have come to such untimely ends. This is the stuff of tragedy. But Murtaza Bhutto’s killing also blindingly reveals the depths to which we as a society are descending. True, no one is above the law, neither a hari nor a wadera. Even so, it is not much of a society when the Kalashnikov, that accursed legacy of our Afghan involvement, becomes the ubiquitous symbol of enforcing the majesty of the law.

If Murtaza Bhutto was wanted by the police, and even if he had been booked on specific charges, could the Karachi police not have gone about apprehending him in a less gruesome manner? If Murtaza Bhutto had to be apprehended, the police had the entire day before them to do this. Instead of which they allow him to leave his house at around six in the evening and then lie in wait for him when he returns after addressing a public meeting. It is also not as if a stray bullet hit Murtaza Bhutto. He was hit by at least six bullets, which should give an idea of the withering fire to which his vehicle was subjected. Wearing the uniform of the state does not give anyone the licence to kill. It entails a special responsibility to use force only as a method of last resort and even then not to use it indiscriminately.

According to Press reports, the police kept firing for nearly half an hour, which does not exactly bespeak a tempered use of force. Furthermore, even when the firing had died down, the injured, including Murtaza Bhutto, were not removed to the nearby Mideast Hospital immediately but after an inordinate delay. Were the police on the scene of the clash paralysed by the audacity of the deed they had committed or was it a spirit of vengeance at work against someone who had “raided” two CIA centres (as the police Press note says) for the release of an arrested comrade?

Official inquiries in this country are usually sham affairs in which the truth is often concealed rather than exposed. But since on this occasion it was Mir Murtaza Bhutto and not someone else who fell a victim to police highhandedness, let us hope that for once a proper inquiry is conducted, on the basis of which action is taken against anyone who may have exceeded his authority or limits of moderation and restraint so very essential in a situation like this.

When the initial sense of grief over Murtaza Bhutto’s death subsides, hopefully after an impartial inquiry has shed light on the murkier aspects of this tragedy and action has been taken against the guilty, the government must take urgent steps to put a check on the growing brutality of the police and, at the same time, think hard about reforming the police system as a whole, beginning preferably from Karachi.

***

LEGHARI INVOKES ARTICLE 58-2(B): NA DISSOLVED

DAWN November 6, 1996 (Editorial)

Another debacle — and the challenge ahead

HATEVER else may be said of the President’s decision to dissolve the National Assembly and send Ms Benazir Bhutto’s government packing, surprise is not a reaction that it will evoke. The precise form and timing of the government’s demise may not have been known but that it was in deep trouble and indeed virtually paralysed was known to all but the most optimistic or the congenitally purblind. Ms Bhutto’s troubles were largely self-inflicted. She could not control corruption and she could not give the country anything approaching good governance. Admittedly, Ms Bhutto had not inherited an easy economic situation but the pain that came with this was aggravated by ostentation and the widespread conviction that while things were getting worse for the common man, the rich and the powerful were having a merry time. Not to be discounted also is Ms Bhutto’s arrogance of outlook which made it difficult for her to accept mistakes or even to acknowledge reality. This in the end proved to be her government’s undoing. Where she should have been prudent she was needlessly reckless, picking an entirely avoidable clash with the Supreme Court and straining her relations with the President who earlier had been extending his ungrudging support. Even when all the world was cautioning Ms Bhutto to tread carefully and to read the emerging writing on the wall, she persisted in her wilful ways. Her strength primarily had rested on the support of the President (who at one time was perceived as being her man) and the perceived neutrality of the army. With the President going on the war-path, Ms Bhutto’s position became untenable. Four National Assemblies dissolved in just over eight years: this record does not say much for Pakistani democracy. The only representative government in Pakistan’s history to have completed its term was that headed by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and even that came to a sticky end. True, in a society where the tradition of authoritarianism has struck deep roots, there are vested elements which have no stake in the survival of democracy. But it is equally true if not more that the guardians of democracy have often turned out to be the worst enemies of democracy. Mian Nawaz Sharif was not brought down by any perverse mixing of the stars but by his own rashness and heedlessness. Benazir Bhutto need not have tempted the fates in the manner she did. What is it that makes our political class so oblivious of ordinary calculations? Or what is it that drives it to court disaster time and again? These questions will be asked as preparations get under way for the election promised for February the 3rd, 1997. This summer voices were heard advocating the merits of a longer interim period so hat accountability was carried out and the national stables cleansed before the holding of elections. It would be tragic if these voices were heeded because Pakistan throughout its history has paid a heavy price for constitutional deviationism.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Benazir Bhutto’s return to Pakistan in 1986 and her swearing in ceremony in 1988

A 'No Confidence' vote is held against the PPP (1989)

Benazir Bhutto’s government is dismissed for the first time in August 1990

Benazir Bhutto’s government is dismissed for the second time in December 1996

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature