Special report: The enduring vision of Iqbal 1877-1938

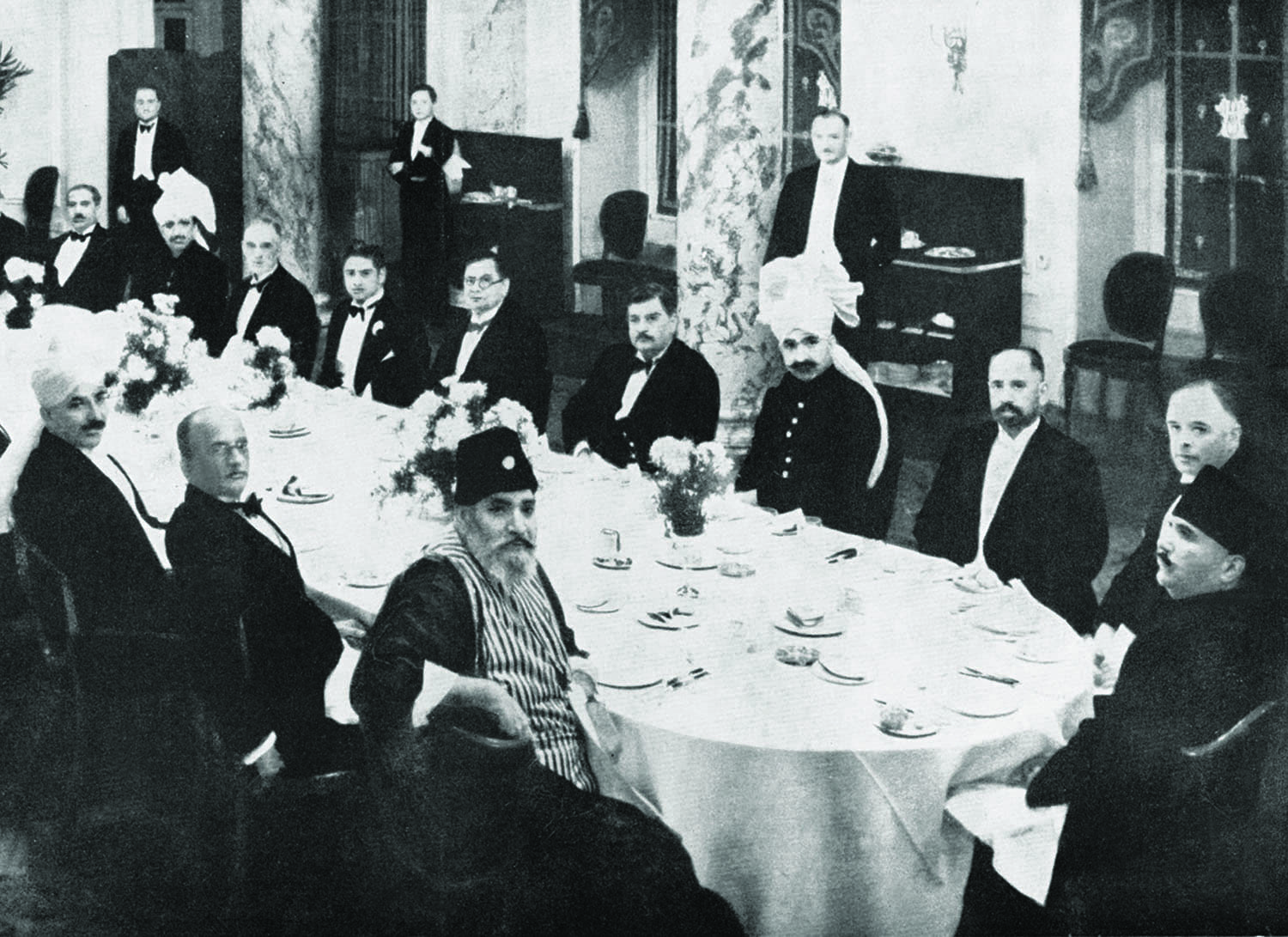

Allama Muhammad Iqbal was a distinguished poet, a brilliant scholar and a gifted philosopher, but, above all else, he was a true visionary. Pakistan was fortunate to have him as its ideological founder. It was at the Allahabad session of the Muslim League in 1930 that Iqbal became the first politician to articulate the two-nation theory that ultimately led to the creation of Pakistan on August 14, 1947. | Photo: The Allama Iqbal Collection in the possession of Muneeb Iqbal

The name, not the philosophy, lives on

By Khaled Ahmed

PAKISTAN’S ideological journey has reshaped the great poet-philosopher Allama Muhammad Iqbal into a patron of its hardening worldview. Reviewing how he has been ‘reinterpreted’ into an ideological platitude is now hazardous because of his state-approved and clerically-backed identity as an orthodox thinker opposed to all modernist revision. At times, secular commentators longing for an identity rollback consign him to the category of ‘orthodox’ while praising Sir Syed Ahmad Khan as the true modernist. There is, however, steady evidence from his life that defies this orthodox labelling.

The climactic moment in Iqbal’s relationship with Pakistan came on December 25, 1986; some 48 years after his death. It happened during a national seminar presided over by General Ziaul Haq in Karachi on the birth anniversary of the founder of the state, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah. The topic of the seminar was, What is the Problem Number One of Pakistan? Present among the invitees was the son of Allama Iqbal, then a sitting judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. In his speech on the occasion, Justice Javed explained why his father was opposed to Hudood (Quranic punishments) which Gen Zia had promulgated in Pakistan.

The controversial phrasing from the Sixth Lecture in Allama Iqbal’s book, The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, was: “The Shariat values (Ahkam) resulting from this application (e.g. rules relating to penalties for crimes) are in a sense specific to that people; and since their observance is not an end in itself they cannot be strictly enforced in the case of future generations.”

The reaction from Gen Zia was dismissive of Allama Iqbal rather than the Hudood he had imposed to appease his vast hinterland of clerical support. He had gotten into trouble with the clergy when his Federal Shariat Court decided that since stoning to death (Rijm) was not mentioned in the Quran it could not be a Hadd, that is, a punishment in the Penal Code. He had to change the Court to retain Rijm.

But Iqbal was prophetic: Pakistan has not stoned a single woman to death despite Rijm being on the statute book, nor has it been able to chop off hands for stealing. More literalist Iran gave up the ghastly practice of Rijm in 2014.

Pakistan is disturbed today by the continuing practice of bank interest after the Federal Shariat Court banned it in 1991 as Riba (usury) specifically mentioned in the Quran as also by Aristotle in his Nicomachian Ethic. Islamic banking which actually excludes the taking of Riba does so under a policy of complex self-confessed Heela (subterfuge).

In his publication Ilmul Iqtisad (1904), Iqbal’s first book in Urdu as an introduction to how a modern economy worked, he explained and clearly accepted bank interest as the lifeblood of commerce, knowing that it was considered banned by the clerics and accounted for so few Muslims in India’s commercial sector. He did so by accepting Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s view that “interest-banking was not the same as Riba/usury”.

HUDOOD AND IJTIHAD

Iqbal couldn’t have found approval in the Pakistan of today, much like Jinnah himself after he declared his preference for the Lockean state on August 11, 1947. To extend the argument, Iqbal was also opposed to the Fiqh (case law) favouring the Law of Evidence that discriminated against women and the non-Muslim citizens of the state. That he was unhappy with and scared of the traditionalist Ulema is testified by his arguments in the Lectures; there is also evidence that he inclined to a ‘liberal’ version of Islam in the new state.

Towards the end of his life he was collecting material to write on Fiqh and had been corresponding with the traditionalist Ulema to elucidate points that he presumably wanted discussed in his new work. He was not a trained scholar (Aalim) and was not accepted as such by the ulema, but he thought himself qualified to produce a work of Ijtihad (reinterpretation).

His son, the late Justice Javed Iqbal, wrote: “The Jinnah-Iqbal correspondence, discussing shariah, points to the establishment of a state based on Islam’s welfare legislation; it does not propose that in the new state any laws pertaining to cutting of the hands (for theft) and stoning to death (for fornication) would be enforced.”

According to Javed Iqbal’s biography of Allama Iqbal, Zindarood (1989), Allama Iqbal read his first thesis on Ijtihad in December 1924 at the Habibya Hall of Islamia College, Lahore. The reaction from the traditionalist Ulema was immediate: he was declared Kafir (non-believer) for the new thoughts expressed in the paper. Maulavi Abu Muhammad Didar Ali actually handed down a Fatwa (edict) of his apostasy. In a letter written to a friend, Iqbal opined that the Ulema had deserted the movement started by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and were now under the influence of the Khilafat Committee from which he (Iqbal) had resigned.

Allama Iqbal’s intent in reinterpreting Hudood becomes clear when he quotes Maulana Shibli Numani, who had written Seerat-un-Nabi, his renowned multi-volume biography of the Holy Prophet: “It is therefore a good method to pay regard to the habits of society while considering punishments so that the generations that come after the times of the Imam are not treated harshly.”

LIKE NO OTHER

Allama Iqbal was a prodigy. In 1885, he stood first in grade one in Scotch Mission School, Sialkot, and began to be tutored in Persian and Arabic in a mosque. He was in class nine when as a teenager he started writing his juvenile poetry in Urdu. He passed matriculation in first division, winning a medal with scholarship. In his first year at Scotch Mission College, he started versifying under the pen-name of Iqbal and was published in literary journals.

He passed his BA exam in first division and won medals in Arabic and English. Three years later, though he passed his MA Philosophy in third division, he was the only one who passed and received the gold medal. He was appointed professor of Philosophy at the Government College, Lahore, chosen by Professor Thomas Arnold – the British orientalist who wrote a book proving that Islam was spread in the subcontinent not by the sword but by humanist preaching – who became his patron.

Iqbal was additionally appointed as the Macleod Arabic Reader at Oriental College, Lahore, on a monthly salary of 72 rupees and one anna. Later, he took time off from Oriental College to teach English at the Government College. His poems had started showing influence from Spinoza, Hegel, Goethe, Ghalib, Bedil, Emerson, Longfellow and Wordsworth.

He couldn’t disagree with Sir Syed Ahmad Khan whom he regarded as the Baruch Spinoza (d.1677) of Islam, rationalising and demystifying the scriptures. His job description at Oriental College included the teaching of Economics to the students of the Bachelor of Oriental Learning in Urdu, and translating into Urdu works from English and Arabic.

PIONEER OF SEPARATION

Lahore lionised Iqbal as the thinker-poet of the city who could spellbind in a Mushaira while publishing erudite papers on such mystics as al-Jili whose concept of Insan al-Kamil was reborn in him with the help of Nietzsche and his ‘superman’ and ‘will to power’ but without Nietzsche’s rejection of morality – his “not goodness but strength” slogan. This was before he went to Europe (1905-08) doing his Master’s and Bar at Cambridge and his PhD with his thesis, ‘The Evolution of Metaphysics in Iran’ at the Munich University, becoming unbelievably proficient in German within three months.

The period 1908-25, back in Lahore, saw him produce some of his Urdu masterpieces while practising law at the Lahore High Court. Reacting to Hindu revivalist movements, he journeyed from his pluralist view of India to a ‘preservative’ posture, advocating separate electorates and developing the first geographical map of ‘separation’ of the Muslim community in the northeast and the southeast within the subcontinent. All-India Muslim League courted him as the leading Muslim genius and listened to his ‘separatist’ thesis at its Allahabad session in 1930.

He contended that his idea of an autonomous Muslim state was not original but had been derived from the Arya Samaj Hindu revivalist vision of Lala Lajpat Rai of Punjab who first recommended ‘separating’ the Muslims. The view he put forward in his address remained pluralist which Pakistan neglected in 1949: “... [N]or should the Hindus fear that the creation of autonomous Muslim states will mean the introduction of a kind of religious rule in such states”.

As for Iqbal’s Nietzschean yearning for self-empowerment, Jinnah was made a practical example of it, as noted oddly by none other than Saadat Hasan Manto in one of his sketches.

Jinnah said this at the 1937 Lucknow session of the League: “It does not require political wisdom to realise that all safeguards and settlements would be a scrap of paper, unless they are backed up by power. Politics means power and not relying only on cries of justice or fair-play or goodwill.”

It was this separate empowerment of Muslims in the face of such Hindu revivalist movements as Shuddhi (purification) and Sangathan (unification) that made Iqbal disagree with the Deobandi scholar Husain Ahmad Madani over the idea of India as a nation-state where Muslims and Hindus would live as one nation.

Like Lala Lajpat Rai, another Indian genius, Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of India’s constitution, wanted Muslims to be given a separate state and wrote his book Thoughts on Pakistan (1941) which was welcomed by Jinnah who then asked everyone to read it to legitimise the League’s campaign for Pakistan.

ON THE SAME PAGE WITH JINNAH

Iqbal’s legally trained mind and his ability to write scholarly tracts quite apart from his ability to write the long poem or masnavi – abandoned by most poets of note after him – qualified him for all the three Round Table Conferences in London to present the case of the Muslims. His Allahabad address at the All-India Muslim League conference in 1930 was actually a learned survey of the nature of the modern state as imagined by such Western philosophers as Rousseau and could not have been comprehended by most Muslim Leaguers still basking in the afterglow of a doomed Khilafat Movement.

Noting that Pakistan’s non-Muslims observe the Independence Day of Pakistan three days earlier, Dawn editorialised on August 11, 2017, on how Pakistan first tried to suppress, then set aside, the August 11, 1947, message of the Quaid-i-Azam at the Constituent Assembly: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed. That has nothing to do with the business of the state.”

It is not only the founder of the state, Quaid-i-Azam Jinnah, that Pakistan has set aside; it is also the philosopher of the state, Allama Mohammad Iqbal, who has been rejected. Seventy years after its foundation, the state is malfunctioning and religion is a major cause of the shifting of its writ to the non-state actors. Denigrated are human rights – of the minorities and women – on the basis of a coercive interpretation of religion. So much so, that the faith-based but unexamined constitutional provisions in Articles 62/63 have finally destabilised governance by causing conflict between state institutions.

The writer is Consulting Editor at Newsweek Pakistan.

This story is the eleventh part of a series of 16 special reports under the banner of ‘70 years of Pakistan and Dawn’. Visit the archive to read the previous reports.

*HBL has been an indelible part of the nation’s fabric since independence, enabling the dreams of millions of Pakistanis. At HBL, we salute the dreamers and dedicate the nation’s 70th anniversary to you. Jahan Khwab, Wahan HBL.*

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

The life and times of Allama Iqbal

SIR Muhammad Iqbal was as much an amazing dreamer as he was a well-grounded politician. The way he constantly walked the fine line separating the two entities was in itself a tribute to a great mind.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Convergence and divergence of views

By Dr Syed Jaffar Ahmed

ALLAMA Muhammad lqbal and Quaid i Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah are undoubtedly the two most important and influential leaders of the 20th century Muslim India. Their mutual relationship, as such, is a subject of substantial significance. Quite in contrast to what official historiography portrays, the two cannot be stereotyped as one and the same. An objective insight would suggest that they had their respective positions, and points of convergence and divergence, on issues of significance.

They, for sure, had a relationship of great respect for each other. Jinnah called lqbal the “sage philosopher” and the “national poet of Islam”, and Iqbal, in a letter to Jinnah, said: “Your genius will discover some way out of our present difficulties”. The divergence of views related to their perceptions of the Muslim community’s interests in India; lqbal seems to be focused on the north western region as the base for the expression of Muslim power, while Jinnah seems to have an all India strategy.

The correspondence between the two is little in terms of volume, but speaks volumes about their reliance on each other, particularly in the context of the Punjab, and also on their respective thrusts. Iqbal wrote to Jinnah 13 letters between May 1936 and November 1937. These were published after lqbal’s death with a foreword by Jinnah. Unfortunately, the replies sent by Jinnah are not available anymore as the trustees of lqbal’s estate, much to Jinnah’s disappointment, could not trace them. Introducing Iqbal’s letters, Jinnah wrote that lqbal’s “views were substantially in consonance with my own”.

The immediate context of the letters is the politics of the Punjab. Following the 1935 Act, elections had to be held in the province. The Unionist Party had already been in power. League contested the elections but lost. Jinnah got into an agreement with Punjab’s premier, Sir Sikandar Hayat, as a result of which League accepted to reduce its role in the Punjab, while the Unionists accepted Jinnah as the representative of the Muslim-majority province in negotiations with the government for the realisation of the central part of the constitution on which Indian organisations had yet to agree.

Jinnah wishes to accord a role to Iqbal in making the League effective. Iqbal takes great interest in the task. He emphasises the need to make the League a mass organisation and also speaks forcefully for addressing the economic problems. However, Iqbal also thinks that Muslim cultural protection and expression had priority over economic considerations. Despite his reservations about the Communal Award, he accepted it for it recognised the separate political existence of the Muslims.

Iqbal also thought that the redistribution of the country should be done in a manner that may consolidate Muslim-majority areas. Earlier in his 1930 Allahabad address, he had denounced the Lucknow Pact, which, to him, “originated in a false view of Indian nationalism and deprived the Muslims of India of chances of acquiring any political power in India”. None else but Jinnah was the architect of the Pact which had brought to him the title of the ‘Ambassador of Hindu Muslim unity’. Iqbal criticised the Pact because it gave weightage to non Muslims in the Punjab and Bengal in return for getting in the Hindu-majority provinces weightage for the Muslims.

Iqbal thought that this compromise hindered the realisation of Muslim power in their majority provinces. Now in his correspondence, he goes to the extent of saying that “the Muslims of north west India and Bengal ought at present to ignore Muslim-minority provinces”. This he thought would be in the interest of the Muslim-majority provinces. One does not actually know what precise replies Jinnah gave to him, but it seems that at least at that stage Jinnah continued with his all India strategy for the resolution of the communal issue and making a convincing case for the Muslims of India.

Reproduced below is a selection of lqbal’s letters, generally beginning with “My dear Mr. Jinnah” and ending with “Yours sincerely, Muhammad lqbal”:

AUGUST 23, 1936

My dear Mr. Jinnah,

There is some talk of an understanding between Punjab Parliamentary Board and the Unionist Party. I should like you to let me know what you think of such a compromise and to suggest conditions for the same. I read in the papers that you have brought about a compromise between the Bengal Proja Party. I should like to know the terms and the conditions.

MARCH 20, 1937

It is absolutely necessary to tell the world both inside and outside India that the economic problem is not the only problem in the country. From the Muslim point of view, cultural problem is of much greater consequence to most Indian Muslims. At any rate it is not less important than the economic problem.

APRIL 22, 1937

As the situation is becoming grave and the Muslim feeling in the Punjab is rapidly becoming pro-Congress for reasons which it is unnecessary to detail, I would request you to consider and decide the matter as early as possible. The session of All-India Muslim League is postponed till August, and the situation demands an early restatement of the Muslim policy. If the Convention is preceded by a tour of prominent Muslim leaders, the meeting of the Convention is sure to be a great success.

MAY 28, 1937

Our political institutions have never thought of improving the lot of Muslims generally. The problem of bread is becoming more acute. The Muslim has begun to feel that he has been going down and down during the last 200 years. Ordinarily he believes that his poverty is due to Hindu money-lending or capitalism. The perception that it is equally due to foreign rule has not yet fully come to him. But it is bound to come. The atheistic socialism of Jawaharlal [Nehru] is not likely to receive much response from the Muslims. The question therefore is: how is it possible to solve the problem of Muslim poverty? And the whole future of the League depends on the League’s activity to solve this question. If the League can give no such promises I am sure that Muslim masses will remain indifferent to it as before.

After a long and careful study of Islamic Law, I have come to the conclusion that if this System of Law is properly understood and applied, at least the right to subsistence is secured to everybody. But the enforcement and development of the Shariat of Islam is impossible in this country without a free Muslim State or States. This has been my honest conviction for many years and I still believe this to be the only way to solve the problem of bread for Muslims as well as to secure a peaceful India. If such a thing is impossible in India, the only other alternative is a civil war which as a matter of fact has been going on for some time in the shape of Hindu Muslim riots.

It is clear to my mind that if Hinduism accepts social democracy, it must cease to be Hinduism. For Islam the acceptance of social democracy in some suitable form and consistent with the legal principles of Islam is not a revolution but a return to the original purity of Islam. The modern problems therefore are more easy to solve for the Muslims than for the Hindus. But in order to make it possible for Muslim India to solve the problem, it is necessary to redistribute the country and to provide one or more Muslim States with absolute majorities. Don’t you think that the time for such a demand has already arrived? Perhaps this is the best reply you can give to the atheistic socialism of Jawaharlal Nehru.

JUNE 21, 1937

You are the only Muslim in India today to whom the community has right to look up for safe guidance through the storm which is coming to north west India, and perhaps to the whole of India. I tell you that we are actually living in a state of civil war which, but for the police and military, would become universal in no time.

I have carefully studied the whole situation and believe that the real cause of these events is neither religious nor economic. It is purely political, i.e., the desires of the Sikhs and Hindus to intimidate Muslims even in the Muslim-majority provinces. And the new constitution is such that even in the Muslim-majority provinces, the Muslims are made entirely dependent on non Muslims.

The only thing that the Communal Award grants to Muslims is the recognition of their political existence in India. In these circumstances it is obvious that the only way to a peaceful India is a redistribution of the country on the lines of racial, linguistic affinities.

Personally I think that the Muslims of north west and Bengal ought at present to ignore Muslim-minority provinces. This is the best course to adopt in the interest of both Muslim-majority provinces. It would therefore be better to hold the coming session of the League in the Punjab, and not in a Muslim-minority province.

AUGUST 11, 1937

Events have made it abundantly clear that the League ought to concentrate all its activities on the north west Indian Musalmans. The enthusiasm for the League is rapidly increasing in the Punjab, and I have no doubt that the holding of the session in Lahore will be a turning point in the history of the League and an important step towards mass contact.

OCTOBER 7, 1937

I suggest that the League may state or re state its policy relating to the Communal Award in the shape of a suitable resolution. In the Punjab and I hear also in Sind attempts are being made by misguided Muslims themselves to alter it in the interests of the Hindus. Such men fondly believe that by pleasing the Hindus they will be able to retain their power.

NOVEMBER 1, 1937

For the present I request you to kindly send me as early as possible a copy of the agreement which was signed by Sir Sikandar and which I am told is in your possession. I further want to ask you whether you agreed to the Provincial Parliamentary Board being controlled by the Unionist Party. Sir Sikandar tells me that you agreed to this and therefore he claims that Unionist Party must have majority in the Board. This as far as I know does not appear in the Jinnah-Sikandar agreement.

NOVEMBER 10, 1937

After having several talks with Sir Sikandar and his friends I am now definitely of the opinion that Sir Sikandar wants nothing less than the complete control of the League and the Provincial Parliamentary Board. In your pact with him it is mentioned that the Parliamentary Board will be reconstituted and that the Unionists will have majority in the Board. I wrote to you some time ago to enquire whether you did agree to the Unionist majority in the Board. So far I have not heard from you. I personally see no harm in giving him the majority that he wants but he goes beyond the pact when he wants a complete change in the officeholders of the League, especially the Secretary who had done so much for the League. He also wishes that the finances of the League should be controlled by his men. All this to my mind amounts to capturing of the League and then killing it. Knowing the opinion of the province as I do I cannot take the responsibility of handing over the League to Sir Sikandar and his friends. The pact has already damaged the prestige of the League in this province; and the tactics of the Unionists may damage it still further.

Yours sincerely Muhammad Iqbal Bar-at-Law

Correspondence has been excerpted from Letters of lqbal, edited and compiled by B.A. Dar, and published by Lahore-based Iqbal Academy Pakistan, 1978.

The writer is Adjunct Professor, Pakistan Study Centre, University of Karachi.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Jawab-i-Shikwah – The message of Iqbal

Translation by Altaf Husain

Complain ye not of heart unkind! Nor speak of tyranny! When Love no bondage knows, Why should Beauty not be free?

Each stack and barn it sets on fire, This lightning-like New Age, Nor howling wild nor garden gay Escapes its flaming rage;

This new fire feeds on fuel old,— The nations of the past, And they too burn to whom was sent God’s Messenger, the last.

But if the faith of Abraham There, once again, is born, Where leaps this flame, flowers will bloom, And laugh its blaze to scorn.

Yet, let the gardener not be sad To see the garden’s plight, For soon its branches will be gay With buds, like stars of light;

The withered leaves and weeds will pass, And all its sweepings old; For there, again, will martyr-blood In roses red unfold. But look! a hint of russet hue, Brightening the eastern skies, The glow on yon horizon’s brow, Heralds a new sunrise.

In Life’s old garden a nation lived Who all its fruits enjoyed, While others longed in vain, while some The winter blasts destroyed;

Its trees are legion; some decay, While others flush with bloom, And thousands still their birth await, Hid in the garden’s womb;

A symbol of luxuriance, The Tree of Islam reigns, Its fruits achieved with centuries Of garden-tending pains.

The robe is free from dust of home, Not thine such narrow ties, That Yousuf thou, whose Canaan sweet, In every Egypt lies;

Thy Qafila can ne’er disperse; Thou holdst the starting bells; Nought else is needed, if thy will Thy onward march impels. Thou candle-tree! thy wick-like root Its top with flame illumes, Thy Thought is fire, its very breath All future care consumes.

And thou shall suffer no surcease Should Iran’s star decline, ‘Tis not the vessel which decides The potency of wine;

‘Tis proved to all the world, from tales Of Tartar conquerors, The Kaaba brave defenders found In temple-worshippers.

On thee relies the bark of God, Adrift beyond the bar, The new-born age is dark as night, And thou its dim pole-star.

The Bulgars march! The fiend of war In fearful fury breathes; The message comes: “Sleepers, awake! The Balkan cauldron seethes.”

Thou deemest this a cause of grief, Thy heart is mortified; But nay, thy pride, thy sacrifice, Thus, once again, are tried. Beneath thy foes if chargers neigh, Why tremblest thou in fright? For never, never, shall their breath Extinguish Heaven’s light.

Not yet have other nations seen, What thou art truly worth, The realm of Being has need of thee For perfecting this earth.

If aught yet keeps this world alive, ’Tis thine impetuous zeal, And thou shall rise its ruling star. And thou shalt shape its weal.

This is no time for idle rest, Yet much remains undone; The lamp of Tauheed needs thy touch To make it shame the sun!

The translator was the editor of Dawn. This translation was first published in Dawn on April 21, 1948, on the 10th death anniversary of Allama Muhammad Iqbal.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Chughtai & Iqbal: Poetry made visible

By S.A. Rehman

WHEN Chughtai was only 29, he brought out a superbly illustrated edition of the Divan of the famous Urdu Poet, Ghalib, and named it ‘Muraqqa-i-Chughtai’. Iqbal contributed a foreword to that publication and described it as “a unique enterprise in modern Indian painting and printing”. Now that the artist and his art have both reached maturity, he has conjured up the practical idealism of Iqbal by the magic of his brush, in what bids fair to be his magnum opus.

The question may well be asked – why has Chughtai devoted the fullness of his artistic genius to this reverential tribute to Iqbal? The answer is plain. Iqbal was the apostle of Muslim renaissance and the ideological inspirer of Pakistan, though he did not live long enough to witness the translation of his dream into reality. He was the Poet-Philosopher of the East and in his time, the best representative and symbol of that culture in which Chughtai has his roots and with which he has maintained a vital contact in his life-work. It was he who quickened the Indian Muslims to [have a] sense of their high destiny.

Iqbal’s versatile genius was equally at home in three languages – Urdu, Persian and English. In the former two, he has left us volumes of exquisite verse that ensure him a place among the immortals of literature. The first collection of his Urdu poems, Bang-i-Dara, came out in 1924. The Bal-i-Jibril (his acknowledged masterpiece in the Urdu language) and the Zarb-i-Kalim, were published in 1935 and 1936 respectively while the Armughan-i-Hijaz (which also included some Persian verse) appeared posthumously in 1938. His central philosophical theme found expression in poetical form in his Persian poem, the Asrar-i-Khudi (1914) and its supplement, the Ramuz-i-Bekhudi (1918). The Persian Payam-i-Mashriq, was written in response to Goethe’s West-Osterliche Divan (1922). The Zabur-i-Ajam and Pas Chih Bayad Kard Cum Musafir, followed in 1927 and 1936 respectively, and his major work, the Javid Nameh – the Divine Comedy of the East – in 1932.

Among his English prose works, pre-eminence belongs to ‘The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam’ which has been published by the Oxford University Press – a monumental book which reveals the immense sweep of his scholarship extending from a profound study of Eastern religious literature to a critical appreciation of modern thought. There is also his Doctorate thesis titled, ‘The Development of Meta-physics in Persia’ (1908).

Iqbal, in his younger days, had passed through the phase of ardent nationalism and sung the songs of a united India marching to freedom from the alien yoke. Though he retained his abhorrence of Colonialism and Imperialism right till the end of his life, he soon outgrew the shackles of territorial nationalism as a political creed. He also condemned blood-relationship as a basis of human unity, describing it as earth-rootedness and a form of barbarism.

“Humanity,” he declared, “needs three things today – a spiritual interpretation of the Universe, spiritual emancipation of the individual and basic principles of a universal import directing the evolution of human society on a spiritual basis.”

These principles he found embodied in the Islamic conception of life, which cuts across all geographical, racial and other social barriers and visualises an ideological community traditional in its values, progressive in its outlook and reconciling the individual and the community, church and state, the ideal and the real into one harmonious whole. He could not countenance the dichotomy of religious and political values that prevailed in the West.

The theistic Islamic socialism which declares land to be for God and makes property a trust in the hands of owners, was, for Iqbal, the social system of the future, in preference to materialistic communism with its class war and regimentation of thought and action. To those who were inclined to cavil at his ostensible parochialism, he pointed out that the object of his Persian poems was not to make a case for Islam. He was aiming at a universal social reconstruction and in the process, he found it philosophically impossible to ignore a social system which expressly avows a universal humanistic code of life. He did not regard philosophy as the handmaid of religion.

Egohood, or Personality, is the keynote of Iqbal’s philosophy. This is for him the touchstone of all art, literature, ethics and religion. That which strengthens the ego is good; that which weakens it is bad. The degree of reality of an individual varies with the degree of the feeling of egohood. Personality is a state of tension and the preservation of that state by sustained conscious effort, tends to make us immortal. Personal immortality is possible but it has to be won. In this life, by educating his ego on the right lines, man can advance to that level of personality which may be termed God’s vice-regency on earth. Such a person is the goal of humanity, the Perfect Man in whom the highest power is united with the highest knowledge and in whose life, thought and action, instinct and reason become one. His advent will establish the Kingdom of God on Earth.

It is beauty allied with power in Iqbal’s poetry that has impelled Chughtai’s gifted brush to transmute his ideas into his inimitable combination of colours and lines that, in the words of Dr. James H. Cousins, “seem to be less lines of painting than of some inaudible poetry made visible”. His sensitivity and the quality of pictorial lyricism that characterise his paintings, have already assured the artist a niche in the temple of fame and I feel sure that the wealth of imaginative truth that he has offered us in this volume will endure in the coffers of time, long after some of the present-day aberrations that pass muster under the generous name of modern art, have sunk into the limbo of oblivion.

Excerpts and Photos Courtesy: Amal-e-Chughtai, published by the Chughtai Foundation Lahore 1968.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

The profession’s lone constant

By Khurram Husain

AMID all the changes that are buffeting the profession of journalism as the digital age undergoes one revolution after another, investigative journalism will remain the one constant. Platforms will change, presentation is being revolutionised while news-gathering is finding vast new areas from where to harvest its content with the proliferation of social media. But the recent past has shown that investigative journalism has retained its ability to rock the established powers in profound ways.

The biggest investigative scoop of recent times was undoubtedly the Panama Papers leak, bringing down governments around the world and justifiably earning for the International Centre for Investigative Journalism (ICIJ) a Pulitzer Prize.

And this is not the only example. The Dawn exclusive headlined, Act against militants or risk international isolation – the story that came to be famously (or infamously) called ‘Dawn leaks’ – created a national stir the likes of which journalism has rarely created in this country.

And, prior to that, the Dawn series of exclusives in collaboration with Wikileaks brought out important details of the war on terror, such as the fact that the drone attacks raining down on the tribal areas were coordinated with the military establishment.

In an era when the news profession is being permeated with commercial interests as well as planted news, and shaped powerfully by the new digital platforms that are ‘democratising’ the dissemination of opinion and information, investigative reporting has emerged as the most resilient and enduring part of the old world of journalism. In the future, too, it will remain the one guiding thread to connect the new journalism with the old. Investigative reporting has retained, if not increased, its significance for three primary reasons. First, the wide array of skills and competencies required to properly carry out investigative work means it can never be ‘democratised’ in the way more standard breaking news, and even more so, opinion, can be.

Second, even as the tools of communication proliferate around the world, it is possible to argue that transparency has not kept pace, and the centres of power have become more opaque even as the tools of surveillance available to them have increased. This increases the demand for investigative work, as was illustrated by the Panama Papers that shone a light on one of the most opaque corners of the world. It was also illustrated by the leaks of Edward Snowden that revealed how the new tools of communication are being turned into instruments of surveillance on a scale the world had never seen before.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, investigative journalism can hold powerful individuals and entities accountable in a way that the normal checks and balances of a democratic system are increasingly unable to. The Dawn stories on Bahria Town’s land acquisition practices, as well as about DHA Karachi, were prime examples in this regard.

The property market of Pakistan is arguably one of the most powerful, and opaque, enterprises in the country. Those at the pinnacle of this racket have a reach deep into the state as well as media with the massive marketing budgets that they control. Only an independently functioning news operation, shielded from the vested interests that otherwise permeate the news profession, could have commissioned and carried stories of that sort.

And the facts that were revealed through them, of large-scale evictions and dispossession of the poor from land that they had lived and worked on for generations to make room for elite housing needs was a rare example of how investigative journalism can bring to light the awful cruelties through which the perks of affluence are gathered.

Investigative journalism differs from its brethren in the breaking news and opinion department in a number of ways. The pursuit of breaking news revolves around gathering the data points needed to unearth the direction in which a large development is moving. Opinion operates in a bazaar where readers can flip through the works of one writer after another until they find someone who echoes their own prejudged notions of how things are. Its tools are rhetoric and the construction of narratives, and the opinion factory harvests facts selectively in order to fit them into a particular narrative. Skilled opinion writers use these tools with varying degrees of emphasis to build and grow their audience.

Investigative journalism, on the other hand, combines all these elements and requires more in the toolkit of the journalist. There is an element of storytelling involved without which investigative work loses its edge. Good storytelling involves connecting the dots, and the more dots that the journalist can bring forward, the more detailed the final story will be. Unearthing the dots with which a story is told requires skills that only journalists with enormous experience have. Any experienced journalist will tell you that the world is littered with dots and data points, but not all of them are reliable, and even fewer of them tell a story that is worth the tell.

In the case of the Dawn investigative story cited above, the biggest challenge was verifying the facts of what actually transpired in the meeting upon which the story was based. “We had to check, crosscheck and recheck what we were told by various people who were part of that conversation,” says Cyril Almeida, the reporter who filed the scoop. “Eventually we ran only with those facts that were narrated to us by a number of different people who attended that meeting. When a number of people recall the same thing from an encounter or a conversation, only then can it be considered reliable.”

The editor stood by the story to the very end; first in an editorial then in a subsequent Editor’s Note. In both of these it was emphasised that the story ran only after verification from multiple sources. This emphasis was necessary because the story was being perceived as a ‘leak’ instead of an ‘investigation’. In a leak, of which there is no shortage in the media, one source tells a reporter something and that one piece of information is run as it has been directly conveyed. In an investigation, such information or lead is crosschecked and verified from other participants.

That process alone can be a big challenge because people can be difficult to reach, or reluctant to talk, or can even give misleading information. Crosschecking, which is at the heart of investigative work, is actually an arduous process and only journalists who have actually performed this task know how intricate and complex it can become, especially in a story which has no hard records or data to use as its raw material, relying exclusively on the recollection of individuals.

It was the same with the story headlined, Greed unlimited. That story was more complex in its contours than the one on acting against militants, and had its dangers even if it did not ignite the fierce backlash that the other story did. Naziha Syed Ali, one of the two co-authors of that story, says their challenge was verification of the facts that they were receiving, which was made difficult because “we were receiving contradictory information from different sources”.

She underlines some of the dangers involved while working on the two stories that she co-authored, the one on Bahria Town and the other on DHA, since they had to interact with the principals in both investigations, but could not give away that they were working on this story. “Since the land mafia was involved, it was likely that they would try to stop us from further working on the story if they found out,” she recalls.

The conversations that take place during verification and crosschecking of details in an investigative story can be enormously delicate. One has to convince or persuade the other party to reveal key information, but reporters cannot give away what they already know, or what they will be doing with the information being furnished.

This is how investigative work differs from leaks, which are more routine and often run without much verification or building the context around the leak to develop a story. As such, investigative reporting is the highest form of journalism. It stands above the pursuit of breaking news and the purveyance of opinion, because the journalist has to marshal up skills and techniques from a wide range before completing the story. It takes the skills of a detective, of forensic examination of data, a wide network of contacts through whom material can be checked and verified, as well as the command of the art of storytelling to be successful.

One critical weakness inherent in investigative work is that it requires time. Investigative reporting cannot be done on a 24-hour news cycle, nor can it be used to fill the pages of a daily newspaper. As newsroom resources come under pressure in the years to come, investigative journalism is likely to feel the pinch more than the others because in the new age, quantity is winning out over quality. Yet the irony is precisely in this, that investigative journalism is what can secure the future of news organisations more than anything else.

This is the fine line into the future that Dawn has begun to walk over the last decade, as the newspaper becomes known for more investigative scoops that challenge the powers of the status quo. In the old days it was enough for a newspaper to simply carry reliable information, but in the years to come, for journalism to matter, it will be necessary to go beyond and unearth the messier reality operating behind the scenes.

The writer is a member of staff.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

The price of saying Pakistan Zindabad

By Abdul Rahman Siddiqi

WHEN Dawn was founded as a weekly in 1941, Delhi was still struggling to recover from its post-1857 Ghadar (Mutiny) trauma. Professor Ahmad Ali’s Twilight in Delhi gave the true picture of a family affected by the event and its home in Bazar Matia Mahal (north of the Jama’a Masjid) just as ours in Mahal Sarai off Ballimaran close to yet another once-royal structure, Masjid Fathepuri.

Mir Nihal, paterfamilias of the Matia Mahal family, was almost a look-alike of my own grandfather, Haji Fazal-ur Rahman, and his two brothers, Khan Sahib Haji Abdul Ghani and Haji Abdul Razaque, the father of the well-known Abdul Khalique Abdul Razaque of Karachi.

Dawn weekly was the first-ever Muslim (Muslim League)-owned and published English-language journal to appear at Delhi. However, unlike the only other English-language Muslim journal, The Morning News of Culcutta, privately-owned and personally edited by Abdul Rahman Siddiqui, Dawn weekly appeared under the editorship of Pothan Joseph, the doyen of India’s English-language press.

Delhi had, nevertheless, been the live centre of Urdu journalism with the advent of Usman Azad’s daily Anjam and Mir Khalil-ur-Rahman’s daily Jang. Older Muslim-owned dailies like Alamaan and Ansari, though still there, had just been pulling on.

When Dawn converted into a daily in October 1942, Jang and Anjam, each thriving in its own slot, were no challenge to Dawn. For the educated Muslim class, Dawn’s appearance was the break of dawn itself. Before Dawn, only The Statesman acted as the voice of Muslim India. Its weekly columns by one Shahid and later by Ainul Mulk were supportive of the idea of Pakistan. The column suddenly disappeared, banned by the Bengal government, and caused much anxiety and resentment in the city.

Arthur Moore (later knighted), the great editor of The Statesman, demanded an immediate lifting of the ban. The government yielded and the popular column was back to its usual slot in no time. The column writer happened to be one Altaf Husain, an officer in the Information Department of the Bengal government. The gentleman soon became the darling of Delhi-wallas. As the Pakistan movement gained momentum in 1944-45 around the end of the world war, Pakistan, until then little more than a slogan, grew as an ‘article of faith’ for Muslim India and Dawn the staple of their daily morning fare.

Some time in 1946, Pothan Joseph vacated the editor’s chair to hand it over to Altaf Husain, the esteemed Shahid of The Statesman. The idiom and tone of Dawn editorials changed dramatically under Husain. It acquired a cutting edge and biting tongue with such hand-crafted expressions as putting chillies on the tender-pot of the Hindu Congress.

I did my Master’s in History and Political Science and left my college (Saint Stephens’) in May 1947. Since my one fond dream was to join Dawn, I dared approach the much-revered and as much-feared Altaf Husain myself at his Sujhan Singh Park residence on Lodhi Road in New Delhi. Altaf sahib lived in a first floor apartment of the housing complex. I approached him with a thumping heart and pressed the doorbell. Presently a young man, almost my own age, opened the door.

“Yes?” he asked.

I told him briefly my particulars and the purpose of my visit. He asked me, “Please come in and have a seat. Father is in his room. I will see if he is free to see you.”

To my utter surprise, it would be hardly a couple of minutes or so when Husain appeared. “Yes, Mr. Siddiqi, what can I do for you?” I spoke of my ambition to join journalism as my profession. “I see …,” he said, and without another word returned to his room to leave me with the young gentleman, his son Ajmal. Altaf sahib returned after about a quarter of an hour or so with a letter which he passed on to me.

“You’d join Dawn as a junior unpaid sub-editor. Take this letter to our news editor for necessary instructions”.

That was the dramatic end of my first-ever interview with the gentleman regarded as the Quaid-i-Azam’s sole spokesman.

I reported to news editor Mahmood Hussain at the Dawn offices located in a Hindu-neighbourhood off Darya Gunj and handed in the sealed letter to him. I found Hussain an extremely kind man. He beckoned me to have a seat, opened the letter to read with a sort of faint and enigmatic smile and told me to start with the morning shift the next day.

News editor Hussain sat at the head of the newsroom. At the long table in front, I recognised at least two of my old friends, Zuhair Siddiqi and Asrar Ahmed. Hussain stood up to take me around and introduced me to my would-be colleagues.

“Here is yet another person looking for his place in the sun via Dawn. He will join you tomorrow”. They all stood up. Zuhair and Asrar welcomed me warmly, while others did with a formal smile. They were Sibte Farooq Faridi, Asiful Haque and one Gardezi.

Amongst the senior staff I met were Mohammad Ahmad Zuberi and Ahmad Ali Khan (later Dawn’s editor). Both were on the editorial side. Unlike Zuberi, later Karachi Dawn’s Senior Assistant Editor and editor of Evening Star, Dawn’s sister publication, Khan would be rarely seen outside his room. Zuberi later founded what is today the Business Recorder. As for Husain, I don’t recall having seen him ever in the office.

One retired colonel Majid Malik (ex-Inter-Services Public Relations, India) would be seen once or twice a week, dressed in a white cotton tunic designed like the one worn as part of battle dress. He did a regular column: ‘Tremendous Trifles’ for Dawn.

Amongst staff reporters were Khalid Ali (Maulana Shaukat Ali’s grandson, later director, External Publicity, Pakistan Foreign Ministry), M. H. Askari, who would write a column for Karachi Dawn, and another gentleman whose name was Manzoorul, or perhaps Zahurul, Haq – a big pan-chewing fellow.

On the administration side were general manager Mohammad Ali and Shamsul Hassan, the father of Khalid and Wajid Shamsul Hussain. Dawn Delhi was printed at the Latifi Press close to the Dawn offices.

After Aug 14, 1947, Dawn carried on its masthead the legend, ‘Published simultaneously from Delhi and Karachi’. In September 1947, however, its offices were burnt down by a Hindu mob to end its status as the only inter-dominion, India-Pakistan daily, even if only for a fortnight or so. The provocation for the Hindu mob was the headline, ‘Pakistan Zindabad’.

I joined Dawn in the first week of June 1947 as an unpaid junior sub-editor and was later given a salary of Rs150 per month w.e.f. July 1, 1947. I continued to work for Dawn till the closing of the Delhi edition, drew my last pay in October 1947, joined the Civil and Military Gazette in November and was appointed its NWFP correspondent. This arrangement continued until July 1950, when I joined the army.

The writer is a retired brigadier and was chief of the ISPR from 1968 to 1973.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Setting up the Muslim mouthpiece

By Wajid Shamsul Hasan

QUAID-I-AZAM Mohammad Ali Jinnah was a firm believer in the freedom of expression. After having taken upon himself the cudgels for fighting for the rights of the Muslims of India as their sole spokesman, Jinnah always wanted English and Urdu newspapers as competitive media organs of the All-India Muslim League (AIML) to counter the Congress press and to correct perceptions in the British media.

Dawn in English and Manshoor in Urdu were his brainchild. Weekly Manshoor was launched in 1938 followed by weekly Dawn in 1941, with Pothan Joseph as editor. My father, Syed Shamsul Hasan, was printer/publisher of both the weeklies. AIML secretary Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan was the man in charge, aided by my father who was AIML assistant secretary for more than three decades from 1914 to 1947.

Aware of the difficulties AIML organs and literature faced, he set up a small printing press on the ground floor of his house, Al-Shams, in Darya Ganj, Delhi, and with the Quaid’s permission, named it ‘Muslim League Printing Press’. Weekly Dawn was first published there. Subsequently, when it gained circulation, its printing was shifted to a bigger plant, Latifi Press. However, Syed sahib continued as its printer and publisher till Dawn’s last edition from Delhi in September 1947. Funded by the Quaid, Dawn had among its trustees his lieutenant, Liaquat Ali Khan. Liaquat, editor Altaf Husain and my father then worked closely to establish Dawn as the Muslim League’s mouthpiece.

In 1947 I was about seven years old when I saw Liaquat and the person I used to call ‘Altaf Uncle’ working together with my father. I remember frequent travels to other cities by Altaf Uncle and my father for court appearances, (because Dawn was being sued frequently). Every time they would return, they would bring sweets and delicacies for us children.

In the National Archives one can find more than 72 volumes of correspondence the Quaid had with various Muslim leaders. Before leaving Delhi, he handed these over to my father for safe custody until such time as “I retire to Malabar Hills, Bombay, and write my autobiography”.

Those documents were so valuable that my father brought trunkloads of them to Pakistan at the risk of his life after the attack on Al-Shams. The first thing Jinnah asked him when he met him in Lahore was about the safety of his papers. He was overwhelmed when he learnt that nothing has been left behind in Delhi.

The National Archives also have hundreds of books and pamphlets printed at my father’s Muslim League Printing Press with the printline, “Printed and published by Syed Shamsul Hasan”. How close my father was to Liaquat could be imagined by the fact that, when our family arrived in Karachi and he came to know Syed sahib had no place to live, he had us shifted from Karachi Cantonment Station to the Annexe of Prime Minister House at 10 Victoria Road, where we enjoyed his hospitality until we were provided an alternative accommodation at 7-Kutchery Road opposite to the Sindh Chief Minister’s House.

As a boy I saw Altaf Uncle visit our house in Delhi and in Karachi. As I did my MA in international relations in 1962, my father wanted me to be a lawyer, while I wanted to be a journalist. He could have got me a job in Dawn but he refused. One evening I ventured to barge into Altaf Uncle’s Bhurgari Road bungalow.

He was surprised to see me alone. He asked me why I was not with my father. I told him that I wanted to be a journalist and he wanted me to be a lawyer. He tried to dissuade me and instead advised me to take the Central Superior Services exam and offered to groom me for it. That is when I learnt that he had been an educationist and civil servant too.

When I insisted on becoming a journalist, Altaf Uncle reluctantly conceded and asked me to see him the next morning in Dawn’s office in New Chali, and, lo and behold, my appointment letter as an apprentice sub-editor was ready with his secretary with a salary of Rs 250 per month. I was just 21 and all those in Dawn were silver-haired seniors, minding their own business.

Meanwhile, as the Jang group was launching an evening paper, Daily News, I was advised by my friends that I would have better opportunities to learn and progress there. So I opted for Daily News, the editor being Shamim Ahmed. Others included, besides present editor S.M. Fazal, legendary fighter for press freedom Zamir Niazi, Suleman Meenai, Khawja Ibtisam Ahmed and journalist and author Muhammad Ali Siddiqi. And as my good fortune would have it, I became the youngest editor of a newspaper at age 28 and never looked back.

The writer is a journalist and was Pakistan’s High Commissioner in Britain.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

The stars that faded away

By I.A Rehman

AMONGST the large number of newspapers that faded away over the past 70 years, two outstanding English-language dailies merit special notice; The Civil and Military Gazette, that had a life of 90 years, and The Pakistan Times, which survived for 40 years less.

The Civil and Military Gazette (C&MG), Lahore, was founded in 1872 to promote the British interest in Punjab, which had been conquered only 24 years earlier, and it gradually won recognition for its quality. Its reputation was considerably boosted by Rudyard Kipling’s association with it.

As the mouthpiece of the colonial government, the paper faced problems as the country’s freedom struggle became intense and it steadily lost ground to nationalist publications. However, the paper’s last English editor, F.W. Bustin, was able to defend his independence by resisting the provincial government’s bid to impose censorship through press advice.

The paper faced a serious crisis in April 1949 when it carried a report from its New Delhi correspondent that Pakistan and India were discussing a plan to divide Kashmir. The ‘patriotic’ national press rose in arms against the daily and manipulated the publication of a joint editorial calling for death to it, something that has caused abiding shame to Pakistan’s media. The government promptly banned the paper for six months. It never fully recovered from the blow.

An attempt to revive the paper was made early in 1960s under the editorship of Zuhair Siddiqui. With its forthright attacks on Ayub regime’s policies, C&MG became quite popular among the discerning readers. But the owner, an industrialist, caved in to the regime’s bullying. The paper folded up in 1963.

The demise of the Pakistan Times (PT) was widely mourned because of the role it had played in securing the people’s respect for an independent press. Launched by the left-leaning Punjab politician, Mian Iftikharuddin, to promote the Muslim League’s cause, particularly in Punjab, the paper started coming out on February 4, 1947, with Faiz Ahmed Faiz as its editor.

The paper was modelled after the leading British dailies. It gave maximum possible coverage to national and international developments, with a strong emphasis on reports from the districts. By the end of the first quarter of the 1950s it had its correspondents in London, Paris and New York (to report from the United Nations). Later on, correspondents were also appointed at Istanbul and Teheran. Besides, it paid special attention to sports and culture and it was perhaps the first Pakistani newspaper to start women’s and children’s pages.

Its consistent opposition to the preventive detention laws of 1949-52, and its call for a fair deal to labour and for land reforms made it popular among the people but a suspect in the eyes of a pro-West establishment.

In 1951, Faiz was arrested in connection with the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case and ousted from journalism for four years though he became the country’s most outstanding and popular poet in those years. The PT absorbed the blow and its influence grew rapidly. Although the state’s Cold War narrative got more and more intolerant of progressive ideas, Mazhar Ali Khan, the new editor, deftly kept the paper out of harm’s way. The paper benefited greatly from commanding the largest territory for an English daily in Pakistan – the whole of Punjab, the then NWFP [Khyber Pakhtunkhwa of today] and Azad Kashmir, with their numerous towns. It became compulsory reading for all classes and professionals. However, it was not allowed in any army mess. That perhaps marked the beginning of efforts to shield the troops against rational, progressive and democratic ideas.

The 1952-57 period was dominated by controversies over Pakistan’s participation in US-sponsored military pacts. PT’s steadfastness in calling for an independent foreign policy continued making it more popular with the people until the influence of the left started declining.

Martial law was imposed in 1958 at a time when the military-dominated national narrative had largely turned the social elite and the professionals in the middle class away from traditional politics and the prospects for democracy looked extremely bleak. The PT’s decision to challenge the martial law regime at the height of its power could well be described as its finest hour.

The martial law regime struck back and seized the paper and its sister publications in April 1959. This part of the PT story has been best narrated by Mazhar Ali Khan himself.

After being sold to the regime’s favourites, PT was made the flagship of the National Press Trust (NPT) in 1964 and the Ayub regime. All subsequent governments used it unabashedly for official propaganda. As a result, the paper started losing respect with its discriminating readers.

The Zia regime’s policy of feeding his favourite publications and individuals with PT’s resources ruined its economy. After a change of ownership, the PT expired in 1996. The building housing the PT offices has been demolished and nobody has thought of at least putting up a plaque to remind the people of the place from where one of Asia’s best edited newspapers was once produced.

The Pakistan Times also made a significant contribution to the journalists’ trade union activities. Further, a good number of journalists who rose to fame at other newspaper establishments had their baptism in journalism at PT. It cannot be said that the paper never faltered because it did so when it put its name to the infamous call to strangulate The Civil and Military Gazette and when it endorsed the dismissal of the Nazimuddin government in 1953.

Zamir Niazi, the authentic chronicler of national media’s tribulations, paid PT and its sister publications a handsome tribute when he wrote: “During the short span of 12 years as free and independent journals, the PPL papers were the only ones which could claim near consistency in their struggle for the freedom of the press and for championing the cause of the downtrodden people of this unfortunate land.”

The writer is a senior political analyst and human rights activist.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Ayub’s attack on Progressive Papers

By Mazhar Ali Khan

The following are excerpts from an article published on February 7, 1970 in Forum, a political weekly published from Dhaka, in which the writer recounted the events of that fateful day in April 1959 when the Press in Pakistan suffered its most grievous blow.

WHEN the people of our land attain full freedom and genuine democracy, and Pakistan’s history is written by honest scholars searching for the truth, and not as a panegyric on, or apologia for, the ruler of the day, the Ayub regime will be found guilty of a long and varied list of heinous acts. It will not be easy for our future historians to determine which single action of the self appointed president and his government of courtiers did the greatest harm to the national interest, for they will have a wide field to survey.

Many will probably conclude that the dictatorship’s gravest crime was its deliberate destruction of Press freedom, because so many other evils flowed from this act of denying to the people of Pakistan one of their fundamental rights. It is, therefore, pertinent to recall the Ayub regime’s first step towards this fascist aim, namely, its attack on Progressive Papers, an institution created under the patronage of the Quaid i Azam.

The dastardly attack was made at dawn on Saturday, April 18, 1959. Two ministers, one a general, masterminded the operations, with their main headquarters at the residence of the Martial Law Administrator of Zone B, and a tactical headquarters at Lahore’s Gymkhana Club.

By midnight the offices of the Progressive Papers – The Pakistan Times, Imroze, and the weekly Lail o Nahar – were surrounded by an array of armed police and CID men, and they were captured as the night shift left the premises.

At the same time, similar detachments besieged the residences of Mian Iftikharuddin, the company’s chairman, who also owned a majority of its shares, and its managing director, Syed Amir Hussain Shah. The police carried search warrants and were authorised to use “reasonable force” to take possession of all documents connected with Progressive Papers.

For some weeks before the event, we had heard rumours that the government was unhappy with The Pakistan Times because it was not giving the regime full support, and, more recently, sympathetic individuals connected with the government had discreetly whispered the warning that ‘something terrible’ would happen to our papers.

We were naive enough to believe that any action contemplated would be legal action of some sort. Our naivety was rudely shattered, and we learnt the lesson that a usurper’s regime, guided by unprincipled and lying toadies, was capable of illegal and unscrupulous action to gain its own ends.

The last warning received by me before the event was at 1.30am, when a friend woke me up to say that he had heard from a minister at the Gymkhana Club that he would be coming to see me at 5am to discuss “the future of The Pakistan Times”. At about 5.30am, the threatened ministerial visitation, which by morning I had begun to discount, materialised. He told me in plain terms that the government had taken over The Pakistan Times. In reply to the protest that this could not be done as there was no law which allowed such action, he said that it “had already been done” and that the Security Act had been amended two days ago to make it possible.

Cutting short the discussion on law and ethics, he said he had come to explain that the government’s only purpose was to oust Mian Iftikharuddin and to change the management. No other change was intended, and, in fact, “better facilities” for work would be made available to the editorial staff. The confused and confusing discussion ended when I said that I would give my decision by the afternoon.

About noon I reached the office, and saw that the takeover was indeed complete. Armed police, with handcuffs dangling from their belts, stood at the gates, and CID men were all over the place. When I tried to open the door to my room, I was stopped by a policeman guarding the sanctum. The managing director’s office was occupied by Mr Mohammad Sarfaraz, the newly appointed administrator, and only at his intervention was I allowed to enter my room.

Sarfaraz gave me the details of the government’s monstrous action, and I saw the relevant orders and notifications which had been issued, clearly showing that the coup was a well planned conspiracy. I also saw a copy of ‘The New Leaf’, the editorial which appeared in the next day’s issues of The Pakistan Times and Imroze. Reputedly the work of Qudratullah Shahab, the then information secretary, it is the stupidest piece of bad writing that has ever disgraced the columns of these journals.

A CID officer conducted a thorough search of my room and took away certain papers and books. The papers included Mr Daultana’s thesis on One Unit, and two letters, one for publication, from Mridula Sarabhai. The books he took away were mostly Soviet and Chinese publications. I pointed out a big pile of American publications on my table, and told him that these too were of foreign origin, but he said, looking rather sheepish, that his government was not interested in them.

I called an informal meeting of the other editors and senior colleagues, and told them that I had decided to resign immediately.

Later in the afternoon, after informing Mian Iftikharuddin, I went to General Rana’s residence. There I was confronted by a minister and a group of senior officials, including Shahab and Sarfaraz. On being told that I had decided to leave The Pakistan Times, they sought to persuade me to change my mind.

When it was realised that my refusal was final, an official pointed out that the Essential Services Ordinance had been invoked, and that I could not resign. I said it would be a novel experiment to compel an editor to continue to work against his will, and if they so desired they could try it. At this the minister said that the ordinance would not be applied to me, and that if I insisted, my resignation would be accepted. Requesting that my name should be removed from the printline, I left the gathering.

During this period, the real story behind the takeover began to unfold. Once the decision had been taken to take over Progressive Papers, the case against them began to be built up. The so called political charges are reported to have been prepared by the director of the Intelligence Bureau, assisted by a brigadier who at that time was grooming himself to become the Goebbels of the regime.

Other Government departments were instructed to dig up anything they could find against the company and its newspapers. This process reportedly went on for many months.

That the charges were utterly false is proved by the fact that, although the company’s files were scrutinised by a team of sleuths for nearly three years, not an iota of evidence was discovered to substantiate any charge or even to pinpoint a serious irregularity.

Since it is plain that the charges against Progressive Papers were fabricated, and would have been thrown out of court even by a third class magistrate gifted with a modicum of honesty and elementary knowledge of legal procedures, the Ayub government’s action, and the kangaroo court which authenticated it, can only be viewed as a medieval auto da-fe, because the only complaint which had validity was that those who owned, managed and guided The Pakistan Times and its sister papers did not share the regime’s faith in its dictatorship, and for this lack of faith they were punished.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Munib Iqbal recounts personal memories of his grandfather Allama Iqbal

Waleed Iqbal discusses Allama Iqbal’s poetry

Faiz Ahmed Faiz on the influences that shaped Allama Iqbal’s oeuvre

Mehdi Hasan renders La Phir Ek Bar Wohi Baada-O-Jaam Ay Saqi

Zia Mohyeddin recites March 1907

Malika Pukhraj renders Tere Ishq Ki Inteha Chahta Hoon

Zia Mohyeddin recites Mahabbat

Farida Khanum renders Na Ate, Humain Iss Mein Takrar Kya Thi

Zia Mohyeddin recites Agar Kaj Ro Hain Anjum

Ustad Amanat Ali Khan renders Lala'ay Sehra

Zia Mohyeddin recites Khizr-e-Raah

Mehdi Hasan renders Talaba'ay Ali Garh College Ke Naam

Zia Mohyeddin recites Shikwa

Madam Noorjehan renders Jawab-e-Shikwa

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature