Special report: At the crossroads 2013-2017

The equation between Nawaz Sharif and Imran Khan more or less decided everything else in the country from 2013 onwards. In the photograph above, Nawaz Sharif is seen here visiting the Banigala residence of Imran Khan in early 2014 in order to build a consensus on security issues. Just months later, the only consensus between the two was on not having a consensus over anything.

Making new futures

By S. Akbar Zaidi

IN July this year when the editorial team at Dawn commissioned a series of special reports on the 70 Years of Pakistan, it chose topics that one would expect. An article on the Founding Fathers, on Ayub, two on Bhutto, one each on Zia and Benazir, and so on. It had planned the series well before commissioning specific writers, and at a time when Pakistan’s politics was probably settled and secure in the leadership of prime minister Nawaz Sharif who was looking forward to an imminent fourth term following the elections next year. The last theme chosen by the Dawn team, to which this essay responds, was, surprisingly, the very prescient ‘At the Crossroads’.

There is no way that in July, the editorial team could have predicted that by the end of the year, Pakistan might, indeed, be at a major ‘crossroads’ yet again. Clearly, the team knew something I didn’t, or had a crystal ball which told them the future. Either that or they played into the permanent cliché which defines Pakistan’s politics, its economy and society, that Pakistan is forever at some crossroads or the other even when things seem quite settled and appear to be going well.

It is this particular unknowability, or the permanence of being stuck at the crossroads, which, for many political and social observers, defines Pakistan. Apart from these themes, there are pundits who are always finding ‘fault lines’ somewhere in Pakistan’s present, while others think that Pakistan moves only from crisis to crisis, yet others insist that Pakistan and Pakistanis are ‘resilient’, so bring on another trauma or crisis, and Pakistan will, as they say, ‘muddle through’.

There is an ahistorical understanding amongst many writers about how events and processes unfold. For others, who come up with a long wishlist of ‘what needs to be done’, there is absolutely no understanding of material conditions and relations which allow for certain developments to take place. Many react to immediate events without understanding what the causes for such events are, and fail to locate them in their specific context. Historians repeatedly emphasise that context matters, that it is critical.

But there is also the converse of this argument, that for social scientists who like to locate their understanding on material and social forces, Pakistan is perhaps one of the most unpredictable places in the world, where events emerge not just to surprise, but to completely disorient our understanding of possible outcomes based on material forces. Social scientists use the term ‘contingency’ for such unexpected events, but in the case of Pakistan, there seem to be far too many.

Just three examples from Pakistan’s very recent history would emphasise this point, that there are far too many ‘unknown unknowns’ (the enchanting term coined by Donald Rumsfeld), things which we could not have predicted or put into our calculations. In 1977, or again in 1999, when Generals Zia and Musharraf had taken over through coups dismissing democratically elected governments, one could not have imagined that they would have survived for a decade in power had it not been for unexpected events, both times related to the invasion of Afghanistan.

Both December 1979 and September 2001 were not events factored into our social, political and class analysis and understanding of Pakistan, and much of the understanding about Pakistani politics and society was unhelpful in explaining dynamic developments at that time.

Similarly, no one could have ever imagined that Asif Ali Zardari would be Pakistan’s president, but the circumstances following Benazir Bhutto’s assassination made something as impossible as that quite real. In each of these cases, the analysis by social scientists had to concede to the powerful hand of contingency and we were forced to only react to the events after the event. Pakistan’s past could not have been foretold.

IS THE PAST RELEVANT?

There are numerous people, including many scholars, who invoke the past as some ideal and idealised moment, hoping to resurrect it in the context of what Pakistan is today. There are those who want a morality and ethics based on the Prophet and his Companions’ time, arguing that only if we return to the values of that era, will we do justice to our existence today.

There are some who repeatedly cite the speeches made by Mr Jinnah, especially his August 11, 1947, speech, arguing that his was the call for tolerance and acceptance of different religious beliefs, if not for an outright call for some vague notion of secularism.

In more recent times, there are still a few who reminisce about Ayub Khan’s golden years wishing they were revived, and an even younger generation which wants Musharraf back and extol some of his perceived virtues – however, no one asks for a return of Zia or his times. Yet, none of these historical imaginaries, whether those which are well-intentioned or are ill-conceived, are possible in the current moment, for times, and their material conditions, have changed.

A ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’ is not possible, for we have lived through a Zia’s Pakistan, and, after so many trysts with destiny, find ourselves in the post-Taliban moment. The contexts of such virtues have changed, for they cannot be mere idealistic thought experiments, but need to be examined in particular material social and political contexts. Jinnah’s famous speech was written in far more friendlier times, when around 12 per cent of the Pakistani population belonged to non-Muslim faiths. Today, that number is less than half of that, even after we have added to that list by declaring some communities non-Muslim. The notion of going to ‘your temple or church’ really doesn’t exist as an option after Zia. Pakistan has changed completely from the time of Mr Jinnah, or even of Mr Bhutto. Jinnah would weep at what many generations have done to the Pakistan he created.

AND WHAT OF THE FUTURE?

One of the first things one ought to learn about social sciences and in studying Pakistan is that we do not, and cannot, make predictions. When the 2013 elections were held, the Herald magazine conducted a poll of prominent political and social scientists to make their predictions (based on some analysis, of course) about the elections. In their foolish enthusiasm, many did, and were off the eventual results by not just a few seats, but by factors many times over.

In 2013, the electronic media was giving Imran Khan an almost certain chance to win the elections outright, and while some thought that Nawaz Sharif would win the largest number of seats, I do not recall any analyst predicting an outright majority for the PML-N.

Besides, even after his name appeared in the Panama Papers, there were very few analysts who thought that this would result in him being dismissed or disqualified. Predictions, especially about elections and political matters in Pakistan, are better left to astrologers and soothsayers, not to scholars trained in social and political sciences.

Yet, we also cannot be so irresponsible or complacent, and not venture forth speculating about the future, having some understanding and learning of material conditions and social processes. One can, at least, analyse class and social forces, look at changing regional and global factors, and, based on this, offer some analysis which, based on present conditions and contexts, would be valid.

One cannot control for the unknown unknowns, but we can make sense of where we are and possible future directions. These do not have to have predictive attributes and are merely speculative and conditional as well as contextual.

As mentioned above, less than six months ago, an emerging consensus was being formed that a Shahbaz-Nawaz victory looked close to certain in the Punjab and across Pakistan, barring some unforeseen circumstances. Those unforeseen circumstances took shape rather quickly, to become a very concrete case for Nawaz Sharif in the form of a trivial clause about a non-disclosure of an income (which wasn’t even received) at the time of filing his election papers in 2013, to bar him from contesting elections.

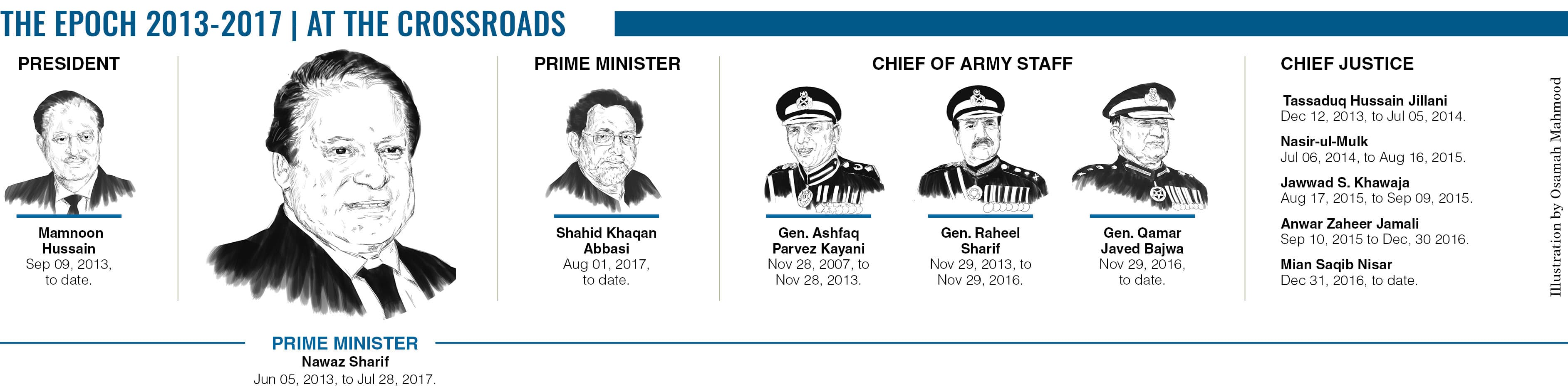

The appointment of Qamar Bajwa as the new army chief, replacing the ever-popular Raheel Sharif, came across as a civilian victory with a smooth transition, clipping the wings of any ambition. Moreover, with the Zarb-i-Azb, followed by Radd-ul-Fasaad, it seemed that the military was finally sincere in breaking the mullah-military alliance.

Pakistan’s economy, too, was growing from strength to strength, with growth at a higher rate for every single year since Ishaq Dar became the finance minister, to be the highest in 11 years. Scores of international journals and newspapers were celebrating Pakistan’s transformation into a newly emerging and strengthening democracy with a buoyant middle class, and stabilising and increasing economic growth. Six months, it seems, is a rather long time in the history of Pakistan where so much which was built on since 2008, seems to have unravelled and come undone.

Nawaz Sharif has been forced out, Ishaq Dar is sent on leave, and the military has started giving numerous signals with clear political messages. First, there was that exchange with Ahsan Iqbal about a speech given by the COAS about the economy, and then there was the military’s central role in the Faizabad sit-in. What does one make of Pakistan’s future? At the crossroads? Again? Permanently?

Despite the recent intrusion into the political sphere by the military, yet again, and the dismissal of Nawaz Sharif, yet again, do not look like a script being repeated from the past. Far too much has changed, and old methods and tactics are unlikely to work. While old forces begin to bring back old politics and tried old methods, new forms of resistance and opposition have also emerged. Even the military is now often challenged, sometimes by the judiciary, more frequently by citizens themselves.

MAKING NEW FUTURES

For the future to change from one which continues to be more-of-the-same, or worse, returns to a discarded and failed model, clearly there is an urgent need for a different politics, a different economics and a better way of living in society. This requires new actors and those who are willing to mobilise on issues which focus on material conditions, and are willing to take bold and necessary steps.

After many decades of annihilation, best demonstrated by the fall from grace of the old Pakistan People’s Party, some progressive voices have begun to emerge, organising themselves around causes which are best represented in the form of political organisation. When even liberals are being accused of being ‘the most dangerous group in Pakistan’, the urgency for progressives to unite against mainstream parties cannot but be emphasised. In 50 years, there has never been a better time, or greater need, for progressive politics in Pakistan. It is time now to make a future far different from the pasts we have lived through.

The writer is a political economist based in Karachi. He has a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge. He teaches at Columbia University in New York, and at the IBA in Karachi.

This story is part 15 of a series of 16 special reports under the banner of ‘70 years of Pakistan and Dawn’. Visit the archive to read the previous reports.

HBL has been an indelible part of the nation’s fabric since independence, enabling the dreams of millions of Pakistanis. At HBL, we salute the dreamers and dedicate the nation’s 70th anniversary to you. Jahan Khwab, Wahan HBL.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

A sisterhood with nerves of steel

By Naziha Syed Ali

“THE truth does not change when a government does. Like freedom, truth is open to misuse, but, again like freedom, it can’t be withheld on that count,” wrote the late Razia Bhatti in one of her searing editorials. These were not merely fine words: Ms Bhatti, editor of the Herald and later of Newsline – not to mention the women journalists who worked with her – stood by those words throughout her career, speaking truth to power no matter how ruthless her adversaries, be they despots, ‘democrats’ or drug barons.

Women journalists like them were never more in need of courage than during the repressive Ziaul Haq years, when they fought not only for the freedom of the press but also against state-sponsored misogyny that impacted their personal and professional lives. By that time, more women had begun to enter the field, especially in the English-language media, and this sisterhood found a collective voice.

That steady trickle of women journalists was to become a flood some decades later as scores of private television news channels began to crowd the airwaves. But it all began with an intrepid few who had the self-belief to break into the male domain that was journalism at the time.

A list of these accomplished women would have to include, among others, names like Najma Babar, Ameneh Azam Ali, Najma Sadeque, Rehana Hakim, Nargis Khanum, Zohra Karim, Maisoon Hussein, Saneeya Hussain and Jugnu Mohsin. A couple of them – Sherry Rehman, one time editor of Herald, and Maleeha Lodhi, the first woman editor of a daily newspaper in Pakistan – have moved on to distinguished diplomatic and political careers.

Among the pioneers was Zaibunnisa Hamidullah who wrote for Indian newspapers before independence. Post-1947, she began writing a column for Dawn, which made her Pakistan’s first female political commentator. She was also founder and editor of Mirror, a unique combination of a glossy society magazine with hard-hitting editorials – the proverbial iron fist in a velvet glove – that repeatedly took Ayub Khan’s government to task. The magazine was banned twice for its temerity.

However, women like Ms Hamidullah were outliers. With its odd hours and somewhat seedy reputation, it was some time before families began to consider journalism a suitable career for their daughters. When Mahnaz Rehman, resident director of the women’s rights organisation Aurat, told her father she wanted to work at a newspaper, he was horrified, even more so because she wanted to join an Urdu newspaper. “English journalism was considered a little more respectable at the time. But I stood my ground, and joined Musawat [the PPP mouthpiece].”

Not only that, but Ms Rehman later became secretary-general of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ), the lone woman holding her own among a sea of men at the noisy union meetings.

Women’s periodicals, among them Aanchal, Bedari and Akhbar-e-Khawateen – the latter being the first women’s weekly in Pakistan – were comparative oases of calm. However, besides offering the standard ‘feminine’ fare catering to the Urdu-speaking public, some of them also carried content on social issues and women’s rights. Shamim Akhtar, editor of Akhbar-e-Khawateen for 22 years, says: “We even did stories based on undercover reporting such as one on a fake pir in North Nazimabad. One story of ours [about David Lean’s relationship with a married Indian woman] even got us into trouble with Dr Israr Ahmed.”

For many women, Dawn, the largest English-language newspaper in Pakistan, was where they cut their teeth in the profession. In fact, editors at the paper actively looked to hire female journalists. Nargis Khanum, who passed away just recently, started off back in 1966 as a reporter covering art and culture.

Shahida Kazi, fresh out of journalism school, joined the same year as a reporter. Although, like Ms Khanum, she had a ‘safe’ beat — health, education and women’s issues — a female reporter was unheard of at the time. “As a feminist and a Marxist, my job was to prove that anything a man can do, I can do as well,” she says. Some of her male colleagues, however, used to call her a ‘meena bazaar’ reporter because they thought she couldn’t cover ‘important’ stories. Ms Kazi forayed into politics in 1968 when she joined PTV, from where she retired 18 years later as senior news editor.

In this era of many ‘firsts’, Zubeida Mustafa joined Dawn as features editor in 1975. The men, an old-school bunch, did not quite know how to react to this young woman. “They would stand up every time I entered the room,” she chuckles. Within a few months, Ms Mustafa was promoted to assistant editor; before her, no woman had been in a position senior enough to have a say in matters of policy or articulate the paper’s stance on various issues through the editorials.

In this brave new world, at least for women, a very mundane problem presented itself – the location, or even the existence, of a ladies’ toilet on the premises. “If I’d asked my colleagues, I think they’d have fainted,” says Ms. Mustafa. “So I’d zip across to the Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, where I’d worked earlier.” Only an accidental encounter one day with the women at the Herald magazine in one of the many corridors in Haroon House solved that mystery.

If journalism was generally a boys’ club back then, the parliament beat was particularly so. But that didn’t deter the feisty Anis Mirza, whose wit and eye for detail livened up her column – ‘From the Press Gallery’ – that she penned for Dawn. In one column she wrote: “Outside the National Assembly … rain washed away the stifling dust, heat and haze of the Punjab. But in the National Assembly, octogenarian Maulana Hazarvi was asking stifling questions on whether or not government provided separate compartments for ladies in rail cars.”

Challenging gender stereotypes – typified by the quaint term ‘lady reporter’ – required dogged determination and, sometimes, the capacity to turn liability into an opportunity. Nafisa Hoodbhoy, who joined Dawn in 1984, got the coveted political beat after she dug into the health beat that she’d been assigned, and started reporting on gunshot victims piling up in hospitals as a result of ethnic warfare raging in Karachi at the time. “After seeing me at every incident, a crime reporter from an Urdu newspaper finally cried out in exasperation ‘Doesn’t Dawn have any male reporters left’?”

Political reporting from the 1980s onwards, especially in Karachi, with newly emerging centres of armed street power and an unaccountable law-enforcement apparatus, meant that journalists – regardless of gender – risked life and limb at the hands of one quarter or the other. Late one evening in 1991, ironically after attending a protest demanding an end to brutality against journalists, Ms Hoodbhoy narrowly escaped falling victim to an attack herself. It was only presence of mind that saved her from two would-be assailants lurking in the shadows near her house. The foiled attack made headlines across Pakistan.

Mariana Baabar, during her 38 years as a journalist at The Muslim, Frontier Post, Nation and The News, knows a thing or two about violence against journalists. Sometime during Nawaz Sharif’s second tenure as PM, the Jang Group was locked in a battle with the government. When the FIA stole the publication’s newsprint, a group of Jang employees, including Mariana, descended upon the law-enforcement agency’s Rawalpindi office to protest.

There they were set upon by FIA personnel, who thrashed them with steel batons. “If I wasn’t wearing my winter coat at that time of year, my injuries would have been far worse,” she says. To this day, she remembers her blood running cold at a remark made by one of the men raining blows upon her. “We killed the wrong bitch,” he hissed. A few weeks earlier, Ms Baabar’s German Shepherd had been poisoned.

These trailblazing female journalists didn’t see their gender as a handicap in their profession (except perhaps for the lack of ladies’ toilets at almost every newspaper in the earlier days!). They simply shrugged and got on with their work.

Sometimes though, they encountered reminders – if inadvertent – of their gender. Afia Salam, the first female cricket journalist in Pakistan, entered journalism with articles she contributed on the sport to the Urdu daily Jasarat. “I was attending a cricket tournament reception where I was introduced to a very senior journalist,” recalls Ms Salam. “He greeted me by saying, ‘Oh, so you’re Afia Salam. But you write very well!’”

Later in her career, Ms Salam became editor of The Cricketer, the only woman editor the publication has ever had. One day, the magazine received a letter from a reader in India saying, ‘I think your editor is a woman, but surely that can’t be. Please clarify.’ Nevertheless, there were some drawbacks to being a female sports journalist; she couldn’t, for instance, visit the players’ dressing rooms or socialise with them, which made it difficult to get the inside news.

For women journalists, Gen Zia’s years in power were among the most challenging, when they were in the forefront of the resistance to the regressive and discriminatory laws being enacted at the time. Zohra Yusuf, editor of Star Weekend, was also a founder member of the Women’s Action Forum, and the paper was a vocal advocate of women’s rights. “In fact, I was accused of turning it into a feminist paper,” says Ms Yusuf. “But it gave me enormous satisfaction that we gave so much space to women’s issues and violence against women. The paper was a pioneer in that respect while Dawn’s women’s page was still offering recipes.”

There were also other ways of resisting the military regime. Ms Mustafa recalls Gen Zia’s government refusing to include her in a press contingent accompanying him on a trip to Southeast Asia, even though she had been nominated by the then Dawn editor, Ahmad Ali Khan. When Begum Zia decided to accompany her husband, Ms Mustafa was extended an invitation, but she turned it down. “I said I wasn’t going to entertain her, nor did I need her to be my chaperone.”

A few years later, however, when Benazir Bhutto came on the scene, women journalists had a distinct advantage. They enjoyed an access to her that their male colleagues did not. For instance, after being manhandled while leading a procession from Islamabad to Rawalpindi, Ms Bhutto, who was in the opposition and pregnant at the time, confided in Ms Baabar about her fears for the baby’s well-being in a late-night chat at her home in Islamabad.

Ms Hoodbhoy for her part says, “Benazir’s preoccupation with what people might think about her, an unmarried woman in a male-dominated society, opened up new vistas for me in terms of home visits, exclusive interviews and accompanying her in private vehicles.”

Today, women journalists are pushing the envelope further, especially in television. With gender lines becoming more blurred, women are covering election rallies, protests, terrorist attacks, etc. They are now an unstoppable force.

The writer is a member of staff.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

***

NAWAZ SHARIF RETURNS

DAWN June 06, 2013 (Editorial)

Three is history

THE tables have turned. Mian Mohammad Nawaz Sharif is back in the prime minister’s chair and Gen Pervez Musharraf is under arrest and facing trial. Mian Sahib is the first man to be elected prime minister in the country for a third time. He is unparalleled as a Pakistani head of government ousted in a military coup and brought back by popular vote. There may be more reasons why the occasion needs to be celebrated just as it has to be marked with some solemn vows. In his speech after his election in the National Assembly by an overwhelming majority, the new prime minister made a conscious effort to build on this reputation as a politician who has undergone the course and has learnt.

Five years ago, the stress was on reconciliation, on the need to shape a national policy on many issues. Those who spoke after Mr Nawaz Sharif’s speech in the assembly on Wednesday [June 5] did highlight some of the issues where consensus is hard to achieve: law and order in Karachi and elsewhere, and lack of local governments. The new prime minister’s promise in dealing with these problems lies not so much in the numbers he has by his side but in the belief about the security and resultant maturity of the elected collective. Politicians will err and then correct their mistakes so long as they have the time and the security of tenure.

***

ATTACK ON ZIARAT RESIDENCY

DAWN June 16, 2013 (Editorial)

A sad day

A DAY that began with the desecration of a secular shrine, the Ziarat rest house where Mohammad Ali Jinnah spent his last days, continued with another episode of violence in Quetta. The perpetrators of these two crimes could well be worlds apart in terms of ideology, but so is the vision for Pakistan of one of the great, secular, non-violent leaders of the 20th century and the reality of Pakistan today. That the Baloch Liberation Army knew exactly what it was doing in destroying the Ziarat rest house is obvious.

Was the bombing meant as a cynical welcome for the new Balochistan government, led by the moderate Baloch chief minister Abdul Malik? The BLA has over the years reserved an almost equal fury for the establishment as it has for Baloch politicians who advocate the federation of Pakistan. But clearly, whether the violence being perpetrated is the work of separatists or religious extremists, the establishment’s approach is not working. Why not? In that answer lies an even more depressing truth.

***

MAMNOON REPLACES ZARDARI

DAWN September 10, 2013 (Editorial)

Colourless presidency

WILL we have to keep ‘mum’ now that a ‘Noon’ man has settled into the president’s office? That would be further depriving the deprived. Pakistanis have come to depend a lot on the presidency to keep them thoroughly entertained. There have been military and civilian presidents adept at hatching conspiracies and overthrowing elected prime ministers. Nevertheless, Asif Ali Zardari took to the presidency like no other leader did before him.

Mr Zardari’s departure marks the end of an era when presidents made headlines by putting the nation in a state of turmoil. Now we are left confronting a canvas without colour. Newspapers and television will be all the poorer following the switch to new times. Mr Mamnoon Hussain will take a back seat as the primetime presidency show comes to an end. The loss will be keenly felt.

***

ZARB-I-AZB LAUNCHED

DAWN June 16, 2014 (Editorial)

North Waziristan operation

AT long last, the operation the country has needed against militants in North Waziristan Agency is under way. According to the ISPR, Operation Zarb-i-Azb has commenced and the goal is to “eliminate these terrorists regardless of hue and colour, along with their sanctuaries”. At this early moment, there must be hope that finally the government has accepted that dialogue with the outlawed TTP has run its course and that the army-led security establishment has abandoned its good Taliban/bad Taliban dualist policy. Certainly, there have been enough meetings between the civilian and military principals in recent days. But meetings do not make for a workable plan that will involve energising all the levels down the chain of command to approach their job with an urgency and seriousness like never before. For that, surely, the political leadership needs to take centre stage. The country needs leadership, it deserves leadership — will the prime minister step up to provide it?

***

IMRAN, QADRI BEGIN DHARNA

DAWN August 17, 2014 (Editorial)

An unreasonable demand

THE PTI and Tahirul Qadri have separately played their cards — they have showed the kind of street support they command and they have made known their set of demands. To the extent that Imran Khan has demanded electoral reforms be enacted by the government, the PTI’s claim can and should be countenanced and worked on by parliament. As for much of the rest of the PTI’s and Mr Qadri’s demands, the PML-N government, mainstream political parties and parliament can rightly dismiss them. For why should Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif resign a year after winning an election widely perceived to be credible and acceptable? Surely, street power cannot once again become an acceptable means to bring down a democratically elected government — because if the PTI and Mr Qadri’s supporters were to achieve it today, then what is to stop anyone else from marching to oust the government that will replace it or the one after that?

The present crisis only truly became a crisis when the government panicked and tried to scuttle the protests. Until the very end, when the government finally showed restraint and calm, it was more the mishandling by the government of the evolving situation that raised the political temperature than anything the PTI or Mr Qadri had done.

***

SIT-IN KEEPS CAPITAL ON TENTERHOOKS

DAWN September 02, 2014 (Editorial)

Army’s questionable decisions

THE carefully constructed veneer of neutrality that the army leadership had constructed through much of the national political crisis instigated by Imran Khan and Tahirul Qadri has been torn apart. First came the army’s statement on Sunday [Aug 31], the third in a series of statements in recent days on the political crisis, which quite astonishingly elevated the legitimacy and credibility of the demands of Imran Khan, Tahirul Qadri and their violent protesters above that of the choices and actions of an elected government dealing with a political crisis. Consider the sequence of events so far. When the army first publicly waded into the political crisis, it counselled restraint on all sides — as though it was the government that fundamentally still had some questions hanging over its legitimacy. Next, the army crept towards the Khan/Qadri camp by urging the government to facilitate negotiations — as though it was the government that was being unreasonable. Now, staggeringly, the army has ‘advised’ the government not to use force against violent protesters and essentially told it to make whatever concessions necessary to placate Mr Khan and Mr Qadri. It’s as if the army is unaware — rather, unwilling — to acknowledge the constitutional scheme of things: it is the government that is supposed to give orders to the army, not the other way around. As violent thugs attacked parliament, it was surely the army’s duty to repel them. But the soldiers stationed there did nothing and the army leadership the next day warned the government — which largely explains why the protesters were able to continue their pitched battles with the police and attacked the PTV headquarters.

If that were not enough, yesterday also brought another thunderbolt: this time from within the PTI with party president Javed Hashmi indicating that Mr Khan is essentially doing what he has been asked and encouraged to do by the army leadership. It took the ISPR a few hours to respond with the inevitable denial, but a mere denial is inadequate at this point. The army is hardly being ‘neutral’. It is making a choice. And, it is disappointing that the choice is doing little to strengthen the constitutional, democratic and legitimate scheme of things.

***

MALALA YOUNGEST EVER NOBEL LAUREATE

DAWN October 11, 2014 (Editorial)

Pakistan’s braveheart

COURAGE is not a rare quality in Pakistan. Adversity that would break most individuals has produced some of our finest — human rights activists, journalists, not to mention ordinary people fighting against formidable odds. But Malala Yousafzai is a special case; it’s hard to find such courage in a 17-year-old coupled with a clarity of thought and an eloquence that can make cynics catch their breath and the world sit up and take notice. Yesterday, Pakistan’s braveheart won the Nobel Peace Prize, giving a nation starved of glad tidings and buffeted by crises on multiple fronts, a reason to celebrate. By awarding the prize to an education rights activist, the Nobel Committee has delivered a symbolic rebuke to the forces of regression typified by the likes of the Taliban, Boko Haram and the Islamic State that seek to impose a system in which, aside from a slew of other depredations, children — particularly girls — would be denied the right to education; in effect, deprived of a future.

From a young girl simply wanting to go to school in Swat Valley during the savage rule of the Pakistani Taliban, to a global icon who represents the millions of children out of school in the world, whether for reasons of war, militancy or state neglect — Malala’s story is inspirational on many levels.

Malala’s latest award, while undoubtedly prestigious for Pakistan, should also make us reflect on how the state has failed in its obligations towards the people in many ways. Purveyors of intolerance and bigotry have been tolerated for too long here. Malala’s own struggle was forged in this environment; the fact that she has to remain abroad testifies to the continuing potency of these forces. With five million children aged five to nine out of school, there is no place better than Pakistan to further Malala’s cause in a meaningful way. Finally, the fact that the joint peace prize winner is an Indian highlights the commonality of issues between India and Pakistan; it would serve their people well if these could take precedence over politics. As Malala has said so succintly, “I raise my voice not so that I can shout, but so that those without a voice can be heard.”

***

APS TRAGEDY IN PESHAWAR

DAWN December 17, 2014 (Editorial)

New blood-soaked benchmark

IT was an attack so horrifying, so shocking and numbing that the mind struggles to comprehend it. Helpless schoolchildren hunted down methodically and relentlessly by militants determined to kill as many as quickly as possible. As the country looked on in shock yesterday, the death count seemed to increase by the minute. First a few bodies, dead schoolchildren in bloodied uniforms, then more bodies, and then more and more until the number became so large that even tracking it seemed obscene. Peshawar has suffered before, massively. But nothing compares to the horror of what took place yesterday in Army Public School (APS), Warsak Road. The militants found the one target in which all the fears of Pakistan could coalesce: young children in school, vulnerable, helpless and whose deaths will strike a collective psychological blow that the country will take a long time to recover from, if ever.

In the immediate aftermath of the carnage, the focus must be the grieving families of the dead, the injured survivors and the hundreds of other innocent children who witnessed scenes that will haunt them forever. Inevitably, the hard questions will have to be asked and answers will have to be found. Where was the intelligence? The military has emphasised so-called intelligence-based operations against militants in recent months, but this was a spectacular failure of intelligence in a city, and an area within that city, that ought to have been at the very top of the list in terms of a security blanket. Then there is the issue of the operation to find and capture or kill the militants after the attack had begun. The sheer length of the operation suggests the commanders may not have had immediate access to the school’s layout and there was no prior rescue plan in place. Most importantly, will lapses be caught, accountability administered and future defences modified accordingly? The questions are always the same, but answers are hardly forthcoming.

The questions about yesterday’s attack can go on endlessly. They should. But what about the state’s willingness and ability in the fight against militancy? Perhaps the starting point would be for the state to acknowledge that it does not quite have a plan or strategy as yet to fight militancy in totality. Denial will only lead to worse atrocities.

***

AFTERMATH OF APS MASSACRE

DAWN December 31, 2014 (Editorial)

Military courts: a wrong move

PAKISTAN should not have military courts, not in the expanded form envisioned by the military and political leadership of the country, not to try civilians on terrorism charges and not even for a limited period of time. Military courts are simply not compatible with a constitutional democracy. In the immediate aftermath of the Peshawar school massacre, politicians and the military leadership rightly came together to respond urgently to the terror threat that stalks this country. What they did wrong was to decide on military courts as the lynchpin of a new strategy to fight terrorism.

The question that should be asked is, why is the justice system so poor at convicting the guilty? There are really just three steps: investigation, prosecution and judicial. It is at the investigation and prosecution stages that most of the cases are lost. And where the judiciary is at fault, it is often because of a lack of protection offered to trial judges. Can those problems not be urgently fixed in Pakistan? Does not a democratic system exist to strengthen and buttress the democratic system? Military courts are certainly not the answer.

***

SABEEN MAHMUD SHOT DEAD

DAWN April 26, 2015 (Editorial)

Another voice silenced

THE assassination of Sabeen Mahmud is a desperate, tragic confirmation that Pakistan’s long slide towards intolerance and violence is continuing, and even quickening. In the tumultuous city of Karachi and given the variety of causes Ms Mahmud championed, the security agencies are not the only ones perceived as suspects. Ms Mahmud’s work had attracted criticism and threats in the past, particularly from sections of the religious right. While only a thorough investigation can get to the root of the matter, what is clear is that there is not so much a war between ideas in Pakistan as a war on ideas.

Tragically, the state seems to have all but surrendered to the forces of darkness — that is when sections of the state themselves are not seen as complicit. Dialogue, ideas, debate, nothing practised and promoted peacefully is safe anymore. Instead, it is those with weapons and hateful ideologies who seem to be the safest now. Sabeen Mahmud is dead because she chose the right side in the wrong times.

***

CARNAGE IN KARACHI

DAWN May 14, 2015 (Editorial)

Attack on Ismaili community

IT is the vibrancy and plurality of Pakistan that the militants wish to destroy. In targeting Ismailis in Karachi, the militants have grotesquely reiterated their message to the country: no one — absolutely no one — who exists outside the narrow, distorted version of Islam that the militants propagate is safe in Pakistan. The Aga Khan has spoken of “a senseless act of violence against a peaceful community”. In their hour of desolation, it is only right that the Shia Ismaili community’s supreme leader has taken a dignified line and sought to comfort what will surely be a deeply anxious community. The darkness continues to engulf this country.

The brutal attack also raises some very specific questions in the context of Karachi. There are still areas — several ethnic ghettoes — in Karachi that remain effectively cut off from the rest of the city and where law-enforcement personnel only enter on occasion. Finally, for all the problems with a military-dominated security policy in Karachi, why has the Sindh government allowed itself to become near irrelevant? The civilian side of the state needs to be more influential and assertive in the security domain.

***

NA ADOPTS QUAID’S VISION

DAWN August 13, 2015 (Editorial)

Sign of a course correction?

AT long last, and with one resounding voice, the representatives of the Pakistani people have spoken for the minorities of this country. In so doing, they may have taken a historic step towards a course correction for Pakistan’s future. On Tuesday [Aug 11], the National Assembly passed a resolution demanding that the views of Quaid-i-Azam about the status of minorities, as articulated in his famous speech of Aug 11, 1947, be “regarded as a road map” in the years ahead. Portions of that address, which were suppressed by some of the right-wing governments that followed, were recalled in the assembly.

Nevertheless, for Aug 11, 2015, to be a defining moment, the resolution must form the basis for action. Politicians and the establishment need to take a categorical stand against extremists. For enduring change, school curricula should be purged of prejudiced material, the pluralistic heritage celebrated, and the blasphemy law revisited. Only then perhaps will the words have any meaning.

***

SURPRISE IN LAHORE

DAWN December 27, 2015 (Editorial)

Modi’s visit

IT was a delightful surprise on a special day: Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi stopping by in Lahore to meet Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. On his birth anniversary, the Quaid-i-Azam would surely have approved. Much as Pakistan-India relations have the ability to disappoint and confound, they can occasionally spring a welcome surprise. Deplorable as Mr Modi’s brinkmanship and insistence on a one-point agenda (terrorism) in talks with Pakistan is, his willingness to reverse himself and engage Pakistan should be welcomed. The 25th of December was an auspicious day to mark the possible beginning of a new era of stability in South Asia.

Yet, there are many questions. In Lahore, neither the Pakistani nor the Indian prime minister announced anything meaningful. There is also the issue of how Mr Modi and his government will handle elements hostile to the idea of talks with Pakistan. The days ahead will reveal if Mr Modi is serious about the business of peace.

***

AN ICON PASSES AWAY

DAWN July 10, 2016 (Editorial)

Taking forward Edhi’s mission

ABDUL Sattar Edhi is no more. There is sorrow at his passing and sadness at the pain his 92-year-old body may have suffered in his final weeks. Greater, however, is the feeling of pride that he was from among us, if not quite one of us in the way he lived his life. Edhi: icon, humanitarian, Pakistani – ours. To the end, he put simplicity first and others always before himself. His organs were to be donated, but age and frailty meant only the cornea could be transplanted. Perhaps that final act will draw attention to the desperate shortage of healthy organs being donated for transplant in the country. If only a few of the many who are mourning Edhi’s passing were to emulate his example, many more could live longer. It would also be a tremendous boon to the other iconic institution where Edhi was hospitalised: the SIUT, which heroically continues in circumstances of adversity.

The greatest tribute that could be given to one of Pakistan’s most famous sons would, of course, be to ensure that Edhi’s humanitarian network continues its tremendous work. His worldview was ecumenical and increasingly antithetical to the country he grew old in. If Edhi’s values were superimposed on the Pakistani state, Pakistan would indisputably be closer to the vision of its founding father.

***

SATTAR DISOWNS ALTAF’S REMARKS

DAWN August 24, 2016 (Editorial)

MQM at the crossroads

THE inevitable moment has finally arrived yet there is a feeling of foreboding. Altaf Hussain’s state of mind was no secret, especially to party insiders, but when Farooq Sattar said openly what his colleagues had been saying in private for years, he brought the party to a crossroads that carries as much promise as danger. Even by the erratic standards of Mr Hussain, the rambling tirade he delivered on Monday night [Aug 22] set a new low in Pakistani politics. Besides, it was clear beyond doubt that the man who ruled Karachi via remote control for almost a quarter of a century was now totally disconnected from the realities his party is facing, a bit like those in history who went down shouting orders at armies that did not exist.

The moment carries its dangers. All eyes are now turning to Altaf Hussain, seemingly alone and isolated in London. But will the cadres take their cue from him or the new leadership that is struggling to be born in the new circumstances? With whom will the voters go? Mr Hussain may be down but he’s not out yet, and if he decides to fight back, the future of peace in Karachi could hang in the balance.

***

DEATH PENALTY FOR JADHAV

DAWN April 12, 2017 (Editorial)

Sentencing of Indian spy

THIRTEEN months since the arrest was sensationally disclosed, the case of accused Indian spy Kulbhushan Jadhav has taken a darker turn. Convicted by a military tribunal for espionage and sabotage activities against Pakistan, Jadhav has been sentenced to death. Instantly, the already troubled India-Pakistan relationship has been plunged into deep uncertainty. Despite Jadhav’s conviction, there remain many unanswered questions. Start with the official Indian version of events and the many reports in the Indian media. Simply, the explanations offered by India are not credible. Pakistan has long claimed that outside powers have tried to both meddle in Balochistan and use the border region to destabilise Pakistan as a whole. Jadhav’s arrest and now conviction suggest an effort by the security establishment to put a face on the long-alleged crimes against Pakistan. Jadhav’s case could herald a new, round of covert actions by one country against the other. It can only be hoped that back-channel communications or third-party interventions will help India and Pakistan quickly de-escalate tensions and, if necessary, establish new rules on the spycraft that all countries carry. Surely, there ought to be no space for Indian nationals to be prowling around in Balochistan, let alone unauthorised entry anywhere in the territory of a nuclear-armed rival.

***

ARMY CHIEF CALLS FOR COMPREHENSIVE DISCUSSION

DAWN July 14, 2017 (Editorial)

Debating CPEC

THE army chief’s call for an “open debate on all aspects of CPEC” is to be welcomed. When this newspaper ran the details from the long-term plan developed by the Chinese government for CPEC, people were genuinely surprised to learn that the scope of what is planned under the corridor projects goes far beyond power sector investments and transit trade. To this day there has been no specific denial from the government about the contents of that report, which has lent credence to the idea that what is in fact being developed under the plan is a far larger engagement than the government is willing to admit. An open debate is necessary, indeed vital, given the project’s depth and scope, to help build confidence that it is being pursued with the best interests of the country and its citizens in mind. Thus far that confidence is lacking. It is sad to see parliament and the provincial assemblies neglect their role in promoting such debate, and the political parties themselves are too preoccupied with the politics of the moment to spare a thought for this. Without wider debate, the potential benefits of CPEC will not be felt by the common citizenry, at least not in the shape that we are being told.

***

DAWN EXCLUSIVE MAKES WAVES ( October 06, 2016)

DAWN October 11, 2016 (News Reports)

DAWN JOURNALIST ON ECL

THE name of Dawn journalist Cyril Almeida has been put on the Exit Control List, officials said on Monday [Oct 10] night. It is not immediately known why his name has been placed on the ECL, but it is widely believed that the government restriction on his travel came following the publication of the story titled ‘Act against militants or face international isolation, civilians tell military’ in the Oct 6 edition of Dawn.

***

PM OFFICE AGAIN REJECTS DAWN STORY

IN response to a news report headlined “Act against militants or face international isolation, civilians tell military”, the Office of the Prime Minister has issued yet another statement, strongly denying the contents and rejecting it as a fabrication. This is the third contradiction issued by the PM Office, the first one and then its revised and stronger version being released on Oct 6.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The story that has been rejected by the Prime Minister’s Office as a fabrication was verified, cross-checked and fact-checked. Many at the helm of affairs are aware of the senior officials, and participants of the meeting, who were contacted by the newspaper for collecting information, and more than one source confirmed and verified the details. Therefore, the elected government and state institutions should refrain from targeting the messenger, and scapegoating the country’s most respected newspaper in a malicious campaign.

***

DAWN October 12, 2016 (Editorial)

Reaction to Dawn story

THERE are times in a news organisation’s history that determine its adherence to the highest principles of journalism — its duty to inform the public objectively, accurately and fearlessly.

This paper recently reported an extraordinary closed-door meeting between top government and intelligence officials where the foreign secretary briefed them on what he saw as Pakistan’s growing international isolation; following this, there was a discussion on the impediments in the way of dealing with the problem of militancy in the country. The fallout of the story has been intense, and on Tuesday evening [Oct 11], the government placed Dawn’s senior writer, Cyril Almeida, on the Exit Control List. While any media organisation can commit an error of judgment, and Dawn is no exception, the paper believes it handled the story in a professional manner and carried it only after verification from multiple sources. Moreover, in accordance with the principles of fair and balanced journalism, for which Dawn is respected not only in Pakistan but also internationally, it twice carried the denials issued by the Prime Minister’s Office.

Journalism has a long and glorious tradition of keeping its promise to its audience even in the face of enormous pressure brought to bear upon it from the corridors of power. Time has proved this to be the correct stance. Some of the most contentious yet historically significant stories have been told by news organisations while resisting the state’s narrow, self-serving and ever-shifting definition of ‘national interest’. One could include in this list, among others, the Pentagon Papers detailing US government duplicity in its conduct of the Vietnam War; the Abu Ghraib pictures that exposed torture of prisoners at the hands of US soldiers in Iraq; the WikiLeaks release in 2010 of US State Department diplomatic communications; and Edward Snowden’s disclosure of the National Security Agency’s global surveillance system. Even more so in Pakistan, where decades of a militarised security environment have undermined the importance of holding the state to account — something that certain sections of the media have become complicit in despite their long, hard-won struggle for freedom — such a furore as generated by the Dawn report was not unexpected. However, this news organisation will continue to defend itself robustly against any allegation of vested interest, false reporting or violation of national security. As gatekeeper of information that was “verified, cross-checked and fact-checked”, the editor of this paper bears sole responsibility for the story in question. The government should at once remove Mr Almeida’s name from the ECL and salvage some of its dignity.

***

DAWN November 11, 2016 (Opinion)

TRUTH-TELLING: AN OLD-FASHIONED HABIT

THE age of globalisation has discarded with it some old-fashioned values which are tied to the equally old-fashioned principles of viewing the free press as a watchdog on governance on the one hand, and a vehicle to vent the legitimate grievances of a citizenry on the other. We at Dawn continue to subscribe to this often reviled notion of truth-telling. In the seventy-year-old history of this newspaper, we have sometime shouldered the force of blows aimed against us – by the institutions of state and political parties. But we have endeavoured to adhere to every rational means possible to this anachronistic habit – not least of all, because we are founded by the Quaid-i-Azam, Mohammad Ali Jinnah. To put it more simply, we have endeavoured to continue telling the truth in a relatively dignified way and by whatever legitimate means possible.

Essentially, when our founder, Mr Mohammad Ali Jinnah, established Dawn at Karachi in 1947, we created a dualism or a separateness at Dawn between editorial and management decision making. Contentious issues if any are to be sorted out in a consultative process between the editor of Dawn and the chief executive/publisher who stands at the apex of management – and this is after the publication of any news story – not prior to publication. No other member of the management except the chairman of the Board of Directors at Dawn would participate in this two-way dialogue. We continue to respect this tradition – meaningfully.

Today when state institutions appear to be reprimanding Dawn for the sensibility of its editorial practice, we would do well to remember that government and state institutions in Pakistan frequently exhibit a response that is not carefully thought out and frequently misplaced. Yes, I believe the Dawn editor when he says the story was verified and counter-verified as per our stated principles. Yes, the denials of the Prime Minister’s office were also duly carried. And, yes, we need always to be vigilant with respect to verification procedures, keep the news factually balanced and understand the demands of rationalised national security restraints which are attached to this kind of reportage. But, we at Dawn will, to quote [an] editorial, “continue to defend ourselves robustly against any allegation of vested interest, false reporting or violation of national security.”

That, unfortunately, is one of the short-term disadvantages arising from old-fashioned habit of truth-telling. – Dawn CEO Hameed Haroon

***

DAWN May 12, 2017 (Editorial)

A RIFT ENDS

THE rift was unnecessary, making sensibly handled closure all the more welcome. Eleven days after DG ISPR Maj-Gen Asif Ghafoor tweeted a rejection of a prime ministerial directive — a move that even at the time appeared hasty and ill-thought-out — the civil and military leadership have choreographed the end of a wrenching saga that at the very outset, some seven months ago, seemed vastly overblown. Gratifyingly, the military leadership has now not just publicly reiterated its support for democracy, but also embraced core principles of a democratic state: respect for the Constitution and acceptance of legitimately issued prime ministerial orders. History will judge the current military leadership kindly for its willingness to admit a mistake and stand on the side of principles against expediency and cynically manipulated populism. Both Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and army chief Gen Qamar Bajwa deserve praise for pulling back from the brink. Hopefully, the democratic project will continue without further setbacks. If the end is sensible, the beginning was anything but. Perhaps the most puzzling aspect of the saga has been why the previous military leadership created a national frenzy over a report in this newspaper in the first place. Given the veil of secrecy that the military throws over ongoing internal debates and the self-aggrandising speculation in sections of the media, it is difficult to ascertain in the present tense what may be motivating certain decisions by the military leadership. However, with the exit of former army chief Gen Raheel Sharif and the dismantling of his small but powerful coterie of advisers, it does appear that a desire to seek a full-term extension by him may have tainted the response by the military leadership last October. While that is now history and Gen Sharif has secured for himself a sinecure in Saudi Arabia, perhaps the military leadership needs to address what has emerged as a problem since the transition to democracy began nearly a decade ago: the old rule of military chiefs retiring on time and not seeking an extension needs to be made a norm once again. For reasons of democracy, but also for reasons of the institutional strength and dynamism of the military, regular change at the very top is necessary and desirable. For the civilians, the lesson remains the same: unless decision-making is institutionalised, civil-military dialogue formalised and the institutions of democracy strengthened, democracy here will remain vulnerable to attack. The prime minister and his cabinet are too experienced to justify a whimsical, desultory and closed decision-making process. There is also no room for ego and a sense of victimhood at the very apex of the national policymaking process — if the civilians believe they can carve a better path, why not try and work with the military to do so?

***

DETAILED JUDGEMENT ON NAWAZ SHARIF’S DISMISSAL

DAWN November 9, 2017 (Editorial)

Hopes diminish for former PM

UPON the indignity of disqualification has been heaped further humiliation. The detailed judgement dismissing the review petitions filed by Nawaz Sharif and his family makes for devastating reading. Not only has the court reiterated its total belief that it acted rightly to disqualify Mr Sharif for omitting to declare a nominal salary, it has also called into question the former prime minister’s character, intentions and competence. The tone and tenor of the detailed judgement will likely leave legal purists uncomfortable, with the harsh language and condemnation often veering away from strictly legal interpretations. For Mr Sharif, however, the problems continue to mount. While his demeanour and rhetoric had suggested that he did not expect to receive a sudden reprieve, his path to a return to frontline politics continues to narrow. Perhaps Mr Sharif ought to reflect on his own mistakes that have allowed a political crisis to consume the country. Once the Sharif family was enmeshed in the Panama Papers revelations, it was imperative that the then prime minister give a complete and candid account of his family’s wealth and assets. Instead, Mr Sharif chose the path of obfuscation, evasion and delay. Even now, Mr Sharif appears unwilling to acknowledge the legal dimensions of his political troubles, having forced a return as president of the PML-N while his accountability court trial continues. At some point, Mr Sharif will have to acknowledge that the democratic project is more important than the political fate of any given individual.

With a historic third consecutive on-schedule election less than a year away, the PML-N has an opportunity to convince the electorate that it deserves another stint in power. A fresh mandate, if the PML-N receives one, could help clear the uncertainty that has engulfed the political landscape, while failure to win re-election would render moot a debate on Mr Sharif’s political future. The paramount interest is continuity of the democratic process.

***

BEHIND-THE-SCENE MACHINATIONS

DAWN November 14, 2017 (Editorial)

Meddling in politics

WHAT was widely speculated has been confirmed by one of the protagonists himself. Mustafa Kamal has admitted that the security establishment brokered the already-frayed alliance between his PSP and the MQM-P. The episode is only one of several in recent days that suggest political engineering of the electoral landscape is once again being taken up in earnest. Put bluntly, it amounts to a form of pre-poll rigging to manipulate and undermine the democratic process. Unhappily, not only does it appear that anti-democratic elements in the state believe that meddling is necessary, but that sections of the political class, too, are welcoming this interference. The democratic project is arguably being weakened in fundamental ways. Perhaps the most dispiriting aspect of the latest round of political engineering is how many elements from across the political spectrum are willing to participate in the undermining of democracy and how unapologetic figures such as Mr Kamal are about behind-the-scenes efforts to boost their prospects. Certainly, with a general election on the horizon and the leadership of PML-N, embroiled in conflicts, there has been space created for anti-democratic interference. But the perpetrators of that interference ought to realise that undemocratic politics has failed in the past and will fail in the future.

***

DEAL BRINGS END TO SIT-IN

DAWN November 29, 2017 (Editorial)

The long road to recovery

PICKING up the pieces after a devastating shock to the system is not easy. Pakistan is not the country it was until mere days ago. Yet, failure is not an option and it is time to ask searing questions. Has extremism truly gone mainstream? Or was capitulation by each and every institution of the state to a violent mob a last-gasp attempt at salvaging a modicum of stability in order to allow the state an opportunity to regain its composure before it can press ahead with its counter-extremism project? Surely, decisions made in desperate, fearful moments cannot mean that for all time and for all intents and purposes the country has surrendered to extremism.

What ought to be clear is that business as usual is absolutely no longer an option. The National Action Plan was Pakistan’s halting, uncertain attempt at devising a counter-extremism strategy, but it has gone nowhere. There is simply no measure, no analysis and no assessment that can suggest that Pakistan is a country less threatened by extremism of any and every stripe than it was threatened by a decade ago. More desperately, there is a real sense that the state’s capacity to even understand the scale and scope of the problem has been undermined by its head-in-the-sand approach.

If there is to be a solution — and it is not clear that there is an obvious solution — it may have to start with a simple premise: no more, no longer and never again. A zero-tolerance approach to bigots, zealots and mobs. This country has the greatest of men, the most remarkable of leaders in the 20th century, as its founding father. Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the best of all statesmen, who knew not hate or bigotry or violence, is the reason this country exists. To his ideals we must return, to his vision we must re-commit ourselves. Acknowledge extremism; defeat extremism; and let Jinnah’s Pakistan prevail.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Azadi March 2014

Dawn Leaks 2016

Panama Papers 2016

Pakistan wins ICC Champions Trophy 2017

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature